Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Giant oil companies help get the world into this climate crisis. Are they prepared to help lead the way out? I speak to Lord John Browne, the former

CEO of BP.

Then from liberator to dictator, Robert Mugabe dead at 95. Zimbabwe’s strong man in his own words.

And the African singer, Angelique Kidjo, fled dictatorship in her home country of Benin. I speak with her about the liberating power of music.

Also —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

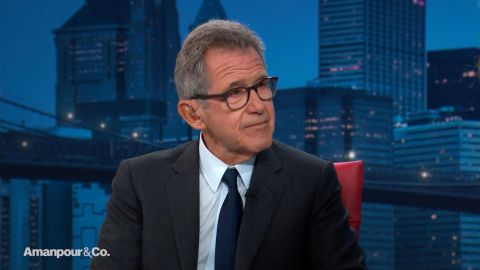

MARC BRACKETT, AUTHOR, “PERMISSION TO FEEL”: Recognize that emotions matter.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The ABC’s of managing our feelings with Mark Brackett, the director of Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York.

As the 2020 campaign focuses ever more intensely on the climate crisis, Democratic candidates are making it abundantly clear whom they hold

accountable, the world’s biggest oil companies and their legions of influence peddlers in Washington. Take a listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOE BIDEN (D), PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: Everything I’ve done has been done to take on the polluters and take on those who are, in fact, decimating our

environment. I mean, it’s been my career.

SEN. CORY BOOKER (D-NJ), PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: I’m sorry. I’m not going to be a president giving tax breaks to people who are polluting folks,

causing cancers, destroying our environment as well.

SEN. ELIZABETH WARREN (D-MA), PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: When you see a government that works great for those with money, a government that works

great for those who can make big campaign contributions and hire armies of lobbyists and lawyers and it’s not working for everybody else, that is

corruption, pure and simple, and we need to call it out for what it is. Fight back.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, if you were to judge by the oil companies branding campaigns, the industry is leading the way to be a clean energy future.

But behind the scenes in Washington, top oil firms are spending millions on lobbyists in a concerted effort to block climate change policies.

John Browne was CEO of BP for more than a decade and he became the first leader of a major oil company to acknowledge the link between fossil fuels

and climate change. But it’s still not clear whether the company actually met his goals for getting carbon production cut. Nevertheless, Browne’s

faith in technology remains unshaken. In his new book “Make, Think, Imagine,” he says enlightened engineering will mitigate the greatest damage

from climate change, from infectious diseases and other major threats.

So, Lord John Browne, welcome to the program.

JOHN BROWNE, FORMER CEO, BP: Good to be here.

AMANPOUR: So, there’s a little bit of good or a lot of bad? You heard what the candidates have said. You have seen where the people are and

where the polls are on the issue of climate change and whom they hold responsible to a large degree. We mentioned that you did come out in 1997

in a speech in Stanford University acknowledging what many industry leaders don’t acknowledge. What made you do it then and are you convinced that BP

has enacted the measures that you called for to cut carbon?

BROWNE: So, I did it then because I believe it was the right thing to do and the evidence was pretty clear that the burning of fossil fuels created

the problem that we have. And so, we had to figure out how we would either clean up the atmosphere or reduce the use of fossil fuels or both. And

that’s where we are today.

AMANPOUR: We’re still there, 20 years later.

BROWNE: We are. We’ve lost a quarter century and I think that’s time which we’ve wasted. Now, the good news is, we have an array of engineering

technologies that we could deploy tomorrow to actually solve this problem is. So, the question is, why don’t we? Why don’t we?

AMANPOUR: Which is what I want to ask you because you are one of those people who is being blamed, maybe not you personally now. But nonetheless,

you know, these big companies and the fossil fuel industry have a lot of political —

BROWNE: Right.

AMANPOUR: — clout and, as we said, armies of influenced peddlers who make sure that what they want gets done.

BROWNE: So, I think we ought to step back and look at the fact base. Right now, the world uses 85 percent of all the energy in the world comes from

fossil fuels, 4 percent from renewables. I’ve been a great proponent of renewables. To change that will take a long time. We will still —

AMANPOUR: How long?

BROWNE: It’s impossible to say. But normally, we’d say it’s going to be decades to change that. It’ll change every year. And we have the

technologies to actually capture the carbon being produced and do something with it, either store it or use it for something else, and we have the

technology to improve other forms of energy. So, what —

AMANPOUR: But are you saying the technologies are there to make a major dent now but they’re not just being used for that?

BROWNE: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: They’re not being — it’s not happening?

BROWNE: The reason is that they’re too expensive. That they cost too much. And so, one of the rules of engineering is the more you do

something, the cheaper it becomes. So, we have to deploy this. And in order to deploy it, we need incentives or specifically negative ones. If

you put carbon in the atmosphere, you should pay a tax. And that —

AMANPOUR: So, rather than subsidize your industries, you need to make your industries and those who pollute pay for that pollution?

BROWNE: Correct. And that tax, I think, wise people would say should not be used for general purposes by government but actually redistribute it to

the population so the tax becomes progressive not regressive. Otherwise, you have the Macron problem where you tax regressively and there are riots.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, you pledged during your time as CEO, as we said, to cut — that BP would cut production of carbon dioxide by 10 percent by 2010.

We don’t see any proof that it’s actually happened. Has it?

BROWNE: Well, we were on route. I left in 2007.

AMANPOUR: Right.

BROWNE: And we were on route. We were rebalancing our production towards gas and we were becoming much more efficient as a company.

AMANPOUR: And you think gas is better than oil because?

BROWNE: Generally, when you — oh, it’s much better than that because when you burn it, you produce less carbon dioxide. So, the problem shrinks.

It’s still a problem but it shrinks enormously.

AMANPOUR: But your successors didn’t do what you had put in place?

BROWNE: So, what happened is the price of oil went up hugely. It went up hugely. And everybody —

AMANPOUR: Everybody got greedy again.

BROWNE: Precisely. Everybody rushed around and said, “We must do more because the demand is infinite. And so, let’s drill. Let’s find things.”

Now, we have calmed down again now. Now, it’s time, I think, to take a more sober and urgent look. So, the oil companies are investing in venture

capital and they’re doing some other things they need to do more.

AMANPOUR: So, you say that and I’m sure it’s true. But they are also, as we mentioned, investing a lot in PR campaigns, lobbying, et cetera. The

influence map of U.K. nonprofit think tank says five publicly listed companies, the major ones, ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP, Total, now spend

roughly $195 million per year on branding campaigns suggesting they support climate actions. But they also spend about $200 million a year lobbying to

delay, control, block policies to tackle climate change.

And, you know, they’re spending on oil and gas extraction is going up by about $115 billion, you know, 3 percent of that directed to local projects.

It’s just — the two don’t equate. What you’re saying should be done and could be done and what is actually happening.

BROWNE: There’s a long shadow. I think the industry has been always behaving that every threat is existential and therefore must be pushed off.

I’ve never agreed with that. The reality is you have to face the future not try and preserve the past. And the future does contain hydrocarbons.

There’s no doubt about it. It contains less hydrocarbons as we go along but it contains new and different forms of energy, including I may say also

nuclear. But, you know, which is — has its own problems, but it’s very important to consumers.

AMANPOUR: Yes. But major leaders have decided to take the populist route and stop nuclear. I mean, Angela Merkel stopped it after the Fukushima

disaster as if that was a nuclear disaster when it was a tsunami that caused that.

BROWNE: And we’ve all watched Chernobyl, you know, and the box says and it makes everyone worried. But this is about decision making, it is not about

engineering.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, again, you have just said that hydrocarbons will be the future, that’s a fact. Is that why you still work for a fossil fuel

company, even despite all that you say?

BROWNE: So, I spent 10 years after BP working in renewable energy. Running the world’s biggest renewable energy dun and it worked out very

well as it became more and more commercial. I went back to invest in gas and oil in that order and I’m very pleased —

AMANPOUR: But why?

BROWNE: Because we need gas. We actually need gas.

AMANPOUR: Why oil then?

BROWNE: Well, because it comes with it, frankly. You can’t be so selective.

AMANPOUR: But you see what you’re saying? You are saying that you have, you know, the right ideas, you know that the technology is there and yet,

we can’t do it. See, basically, what a lot of people are complaining about is that an industry and their lobbyists and the deniers, et cetera, are

trying to convince the world that the solutions to climate change are more of a threat than climate change itself.

BROWNE: As you probably know, I do — I’m not in that position at all. I think, number one, we have the technologies to solve this problem. Number

two, we can’t deploy them. It needs a change in public policy. We absolutely, in order to get the temperature into a range that is acceptable

in some way, we have to charge for carbon. We must have a carbon tax then we can deploy the technologies and we will not — we will still

use hydrocarbons because we haven’t got the means whereby to replace them yet but they’ll be cleaner and cleaner and cleaner. That’s what we’ve got

to do.

AMANPOUR: For those who don’t believe in carbon tax or any kind of tax, is there anywhere where it’s been implemented that it works and you can tell

us as a CEO of a major or former CEO of a major —

BROWNE: A little bit, in Europe. The European trading system has a carbon tax. It had too many loopholes in it. It was lobbied against. But the

trading of carbon in Europe is getting better and better. Loopholes are being closed. And the price is beginning to get to a point where it makes

people think twice about putting carbon in the atmosphere.

So, you can see that the concept is proven. The concept is proven. Now it needs to be scanned (ph).

AMANPOUR: And it’s really getting more and more urgent. If you take a what the U.N. says and it’s the latest report that we’ve got perhaps a

dozen years to get ourselves to a point where we’re not going to go over the tipping point. So, it’s really urgent.

You saw the eclipse that we’ve played from CNN’s town hall on the climate crisis. It was really a major step forward in how it’s covered, how it’s

publicized and how, you know, political awareness. Elizabeth Warren, Senator Warren was asked whether the government should mandate the kind of

lightbulbs Americans should use after the Trump administration announced that its rolling back energy efficient regulations. And she sort of

basically said give me a break. Listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WARREN: There are a lot of different pieces to this. And I get that people are trying to find the part that they can work on and what can they

do, and I’m in favor of that and I’m going to help and I’m going to support. But understand, this is exactly what the fossil fuel industry

hopes we’re all talking about. That’s what they want us to talk about. This is your problem. They want to be able to stir up a lot of controversy

around your lightbulbs, around your straws and around your cheeseburgers.

When 70 percent of the pollution, of the carbon that we’re throwing into the air comes from three industries and we can set our targets and say by

2028, 2030 and 2035, no more.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I mean, she is absolutely right, isn’t she? And she basically says that you can do as much recycling and bulb changing and veganism as

you like, but the big, big issues have to be government mandated and a real sort of massive effort. So, I would assume you agree with that?

BROWNE: I’m completely with that. I think —

AMANPOUR: So, what would you say to President Trump?

BROWNE: So, well, what I would say is what I’ve been saying to every president since I started in ’97 on this journey, which is, you have to

handle the big issue, which is we have to be able to attack directly carbon dioxide going into the atmosphere. Actually, also methane, which he’s

actually removed some of the restrictions on. It’s just as bad. It’s actually worse. Make sure that doesn’t go into the atmosphere. But all

these other issues are very worthy and I’m sure people are interested in.

But Senator Warren is right. They’re not the main event. The main event is to recognize the reality of using hydrocarbons, capturing the carbon and

doing something with it. We cannot let it go into the atmosphere continuously.

AMANPOUR: Again, I guess you’re obviously aware of this massive political shift amongst people, and the young people are the major voters of the

future and they really, really have so much at stake, more than you do, more than I do. And they are making this a political issue. And even as

young as Greta Thunberg who has made a huge splash on the international stage brought the children out all over the world to fight and lobby for

their future.

And yet, you know, she’s been torn apart on social media by people who should know better and including, you know, leaders and deniers in that

realm. You know, the head of — the secretary general of OPEC has said, “Climate change campaigners like her are perhaps the greatest threat to our

industry going forward.” And she tweeted, “There is a growing mass mobilization of world opinion against oil.” Quoting him. “And this is

perhaps the greatest threat to our industry.” Quoting him. “OPEC calls the school strike movement and climate campaign as their greatest threat.

Thank you. Our biggest compliment yet.”

Is it counterproductive of people like OPEC and other fossil fuel industries to, youi know, rain on this activism?

BROWNE: We need activism. We actually need the population to speak to our politicians saying, “You must do something.” Because otherwise, we are

missing the final element here, which is changing public policy. We need that because otherwise, nothing will happen. Costs will remain too high.

Incentives will be in the wrong place and nothing will happen. So, I’m all in favor of people looking at the reality of today. I think the concern

about the local climate, of wildfires, changes in seasons, the melting —

AMANPOUR: Hurricane that we’re watching.

BROWNE: Et cetera, et cetera. The fact that, you know, grapes have to be picked earlier to make wine because it gets too hot. All of these things

should be looked at and we should reflect on those things and say, “Maybe we are causing this and we should do something about it,” and push people

in that direction.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s get back to your book for the last question, “Make, Think, Imagine.” You, obviously, still have a great faith in engineering.

You’ve, you know, outlined how it has transformed society since the beginning of the industrial revolution.

BROWNE: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: But people are becoming incredibly wary and suspicious of all these technology with the surveillance, with the, you know, A.I., with the

sort of uncontrollable nature that they think a lot of it has. Why are you so convinced that this is going to save our species?

BROWNE: Because balance, on vast balance, it does great things for us. It’s helped our health, our longevity, it’s reduced violence in the world,

it’s made things safer. It’s made people have a hope for the future. Some things go wrong, we have to react to them. Some other countries will abuse

the use of these technologies because they have different standards in human rights, but it doesn’t mean to say we throw them away. We have to

keep working on them.

And I say somewhat flippantly but, I think, truly that the solution toward engineering difficulty is not less engineering it’s more engineering.

AMANPOUR: Well, let’s see. Thank you so much indeed, Lord John Browne.

BROWNE: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Thank you.

Let us turn now to Zimbabwe in Southern Africa, which is marking the end of an era. The founding father and former president and dictatorial strong

man, Robert Mugabe, has died today at the age of 95 in a Singapore hospital. And he leaves behind a very complicated legacy. The former

school teacher is still celebrated across the continent for leading his country to independence from white minority British rule.

But unlike Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s heroic freedom fighter, Mugabe became the poster child for a (INAUDIBLE) hellbent on oppressing his

critics and staying in power. I asked him about all of that when we sat down for a rare interview here in New York back in 2009. Here is a little

clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Why is it so difficult to leave power in a reasonable way when you’re up, instead of waiting until it gets to this stage?

ROBERT MUGABE, ZIMBABWE PRESIDENT: Not when — you don’t leave (INAUDIBLE) when imperialist dictate that you leave. The —

AMANPOUR: No, imperialist. You were the president.

MUGABE: No. There is regime change. Haven’t you heard of regime change program by Britain and the United States, which is aimed at getting not

just Robert Mugabe out of power but Robert Mugabe and his party out of power. And that naturally means we (INAUDIBLE).

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: He told me then that only God could remove him from office. So heavily was dug in. Well, nearly a decade later, that God showed up as

mass protests that lead his own military and his own party leaders to turn on him. That was in 2017.

But Zimbabweans still struggle today under Mugabe’s legacy and the rule of his former security chief who is now president.

My next guest chose to flee Africa as a young woman because, at the time, her home country, Benin, in the west, was also suffering at the hands of

the despotic ruler. But Angelique Kidjo’s brilliant creative spirit was her bridge out of the political darkness. She’s one of the world’s great

vocalists and she also uses that talent to fight for human rights everywhere. In her new album “Celia,” Kidjo she plays tribute to the

iconic Cuban salsa singer, Celia Cruz.

(MUSIC PLAYING)

Now, when I spoke to Angelique Kidjo here in New York, we talked about her limitless capacity for finding joy in music even in times of deepest

political despair.

Angelique Kidjo, welcome back to the program.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO, SINGER: It’s always a pleasure to be with you.

AMANPOUR: So, you have literally had a bumpy year. You’re having a bumpy year. There’s so much work that you’re doing right now. I mean, cover

albums, the proms, the famous end of summer music festival at the Royal Albert Hall. You’re curating concerts here at Carnegie Hall.

What is it about right now for you?

KIDJO: I think right now for me have a sense of emergency. In a world where I think we all are losing ground, a lot of things are

happening, there’s a lot of anger and at the sight of the anger, you have a lot of people doing wonderful stuff. But we focus more on the anger than

the positive things.

And for me, music is about building bridges. It’s about bringing people together to a common share humanity. And that’s why I’m like — I’m

devouring everything that comes my way and giving it back to the public. And it has been a really rollercoaster journey that I’m taking but I like

that, it keeps me young.

AMANPOUR: I think it’s amazing. I mean, it keeps you young. That’s great. You definitely look young. We’re about the same age. You’re

outdoing me.

KIDJO: OK.

AMANPOUR: But you’re doing something that you hadn’t necessarily done before. You, as I’ve said, doing some cover albums, cover songs. One of

the bands that’s so well-known too, American and Western audiences, I guess, are the Talking Heads. Erupted on to the scenes in the early ’80s,

I think. And you did a cover last year including a song that you said had inspired you, you know, once in a lifetime. You did their album “Remain in

Light.” do you fancy just giving me some of your joy right now?

KIDJO: Oh, yes.

AMANPOUR: Go on then.

KIDJO: Letting the days go by. Letting the days go by. Into the blue again. Once in a lifetime

AMANPOUR: It’s great, Angelique. It really is. And when you sing, your whole face comes alive and it does definitely impact on the audience. But

what was it about that song and that group? When did you first hear them and how did they inspire you?

KIDJO: I mean, I heard the song “Once in a Lifetime” actually when I arrived in 1983. Three months after I arrived, I was trying to tag along

with friends in my music school. And even though you speak a language and share the same culture, pretty much, with people, it’s always difficult to

leave your home. No one live in exile by choice and find it very fun.

And some of my — the musical friend that I was making at that time said, “Well, let’s go raid my fridge. My parent just fill up my fridge.” I’m

like, “Free food?” Student. I’m tagging along. I’m going along.

AMANPOUR: Raiding your friends’ parent’s fridge?

KIDJO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Here in United States?

KIDJO: No, in Paris.

AMANPOUR: In Paris.

KIDJO: I’m like, “OK. Let’s go for it.”

AMANPOUR: So, you came from the African nation of Benin.

KIDJO: Benin where we have —

AMANPOUR: A communist dictatorship?

KIDJO: — a dictatorship.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KIDJO: For the 10 or 12 years that followed their arrival, music was banned at radio.

AMANPOUR: Literally?

KIDJO: Literally. Our music was banned. Only thing you hear is (INAUDIBLE) day in and day out. Everything (INAUDIBLE).

AMANPOUR: And just so that we understand, that ready for the revolution, the fight continues.

KIDJO: The fight continues.

AMANPOUR: So, they banned pop music or —

KIDJO: All of it.

AMANPOUR: Why? What was the reason?

KIDJO: Well, it’s not — it might make her think about freedom. That’s what music does. If you see any dictatorship that comes in place, culture

is the first thing they crush. Because culture gives people strength to stand up for their right. When you decide to listen to music in your room,

it’s not someone from a government, it’s your will. Your free will to do that. And what that music reveals from your life is something that is

beyond.

AMANPOUR: You know, that’s really an incredible story because, obviously, we remember the counter culture here in the United States, the ’60s, all

the incredible music associated with that during the student uprisings, the protests against Vietnam, political protests. But you’re saying that you

had that in your bedroom in Benin —

KIDJO: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: — when you were growing up.

KIDJO: Absolutely. All the kind of music. I mean, my father and mother – – I’m realizing as I grew older that what I’ve taken for granted is sometimes annoyed me because my mom and dad always used to tell us every

morning, “A human being is not a matter of color. If you come back and you fail you say you’re black, I’m — come on, stop.”

And I grew up and move and it helped me, actually, accept people not thinking the same way I think but allowing the conversation to going on.

We can disagree but as long as we talk to each other, it’s okay. If we stop talking to each other, we go into war. We go into violence and it’s

unnecessary. We don’t need to get there.

AMANPOUR: You know, you were talking to me in the same manner that a general, Jim Mattis, for instance, former defense secretary spoke to me

just this week, talking about how we must, despite our differences, keep talking. Stop being, you know, divided into tribal extreme groups and

treating everybody like an enemy. And you’re seeing it from a very human, personal, cultural view as well.

KIDJO: We tend to forget what is really essential, the core of who we are as human beings. And we get distracted by people’s misery. I don’t living

your life. The choices you make, if you’re not happy with them, change them. Don’t blame me for it. My skin color doesn’t have to come to the

plate. We need to talk to each other. I mean, it’s essential.

AMANPOUR: You are talking about all of this from your own perspective as growing up in Africa under this terrible dictatorship and escaping it. But

now, we are here in 2019 in the United States or in Great Britain, where you have just finished doing the proms or other parts of Europe where this

kind of tribalization, this kind of political hatred is really just driving societies and cultures apart. The racism that we see here in the United

States overtly.

Just talk to me a little bit about what you’re noticing now here in our world, in the free world today.

KIDJO: I think it’s a lot of ignorance, one, and it’s a lot of frustration. When globalization — we start talking about globalizers, I

always say this, globalization doesn’t mean we all have to think the same and we all have to look the same. Because we are a unique. Even though we

belong to the same human family, we don’t think the same way.

In the same family, brothers and sisters with the same education don’t have the same take on every — on the situation they are facing. So, we are

here now and what I hear and it started like way before, I mean, it started 10, 15 years ago.

When people would come to me, young Africans and young from around the world, even in America here, telling me I was doing a signing at

(INAUDIBLE) for my book and a couple of young kids come to me, white kids, not — I mean, we can’t say black are mad, they have reason to — we have

reason to be mad here, telling me we’re going to do a revolution, we’re going to break everything. We’re going to destroy everything. I said,

“Come again? You come to my signing to tell me that? So, you don’t know the person that I am? I’m not for chaos. I’m for construction. I can

understand you guys are angry. I can understand any reason you have to say this. But if you don’t think about building a better society, you are the

great loser because you are the young. You’re going to be the one that pay the cost of the chaos you want to create.

AMANPOUR: So, don’t meet anger with anger —

KIDJO: No.

AMANPOUR: — meet it with a constructive —

KIDJO: Conversation.

AMANPOUR: — conversation.

KIDJO: And — OK.

AMANPOUR: Let’s play then a little clip from Celia Cruz, the cover album that you’ve been doing.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, I hear you singing with me as we play that. Come on, belt it out again.

(MUSIC PLAYING)

AMANPOUR: So, that’s one of her most famous and popular song and it roughly translates, it means, life is carnival.

KIDJO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And she’s country of the greatest salsa stars. So, what is it about her? Why did you decide it? How did she first come into your life?

KIDJO: Well, for me, salsa has always been a huge music scene in Africa, everywhere. There’s no one artist today — Youssou N’Dour started with

salsa. (INAUDIBLE). All of them. All of the guy that started with salsa. So for me —

AMANPOUR: And it’s usually guys.

KIDJO: It’s only guys. That’s what I said. Salsa is a male-dominated form of art. So, for me, OK, as a girl, I’m OK. This music you can’t

touch because it’s only guys that play it. So, comes Celia. And I’m like, “What? What?” She walks on the stairs, she goes, “Hey, guys.” She’s here

to settle. You’re going to learn something right now.

And her song, “Quimbara,” is a lesson of what a voice can be. She used her voice as in these percussive instruments and no one, I said no on until

today can sing like Celia. It’s amazing that we have the same kind of range because most of her song I don’t touch. I don’t change the key of

the song. And from that point on, for me, it becomes clear as a young girl that success or failure has no gender.

And if you don’t believe in yourself, we’re talking about women leadership. What would that leadership be? Are we always going to be when we put in

front of choosing something where it’s out of our realm, we’re going to back and say, “Can I do this?” I’m saying no. I said no to every young

girl and every woman out there, you offer a chance, an opportunity, take it. Learn while you’re doing it. Don’t think back twice. That’s what I

learned from Celia.

AMANPOUR: And just let’s go back to when you’re younger, when she first came into your consciousness. I think you had a bet with one of your

childhood friends that she would, in fact, emerge on to the stage.

KIDJO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Tell me about the homework bet.

KIDJO: The thing is that I saw the post and I said to my friend, (inaudible) are coming to sing. And they they go yes, smarty pant, you

always know everything. A woman singing salsa, where do you come from?

I’m like I’m just saying. They said, “It’s not going to happen. She’s going to be back up singer.” So you want to take a bet?

And if it’s a frontrunner, you do my homework for six months, in and out. The math I give it to you, I hate that.

Before she gave me that, 15 minute big guy singing, and they’re looking at me like “You say you sing? You’re going to lose us.” What? Are you

talking to me? I was like God please let her come and be a frontrunner. And she came out and I’m like —

AMANPOUR: Six months’ free homework.

KIDJO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Because Celia Cruz was the lead singer.

KIDJO: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: And that was the first you sang —

KIDJO: Absolutely. The first — I mean (inaudible) because what I love about Celia is that she never shied away of singing the song that came to

Cuba went to slaves. She always paid tribute to all those gods, those origins. And for me, how’s that, how come she knows all this? It’s great.

AMANPOUR: Talk about that. We’re in the United States right now. You have mentioned the origins, the slave music that she never hid and always

used.

And you sing a lot about dark subjects, as well, with the joyful tone that you have. But look, it is 400 years since the first slaves were brought

over here. Reflect on that but also on how you have really wanted to bring afro music, the afro beat, into a wider world.

And you don’t like the idea of world music, how it’s called. I mean you won your Grammys but in the world category. What does that mean today?

KIDJO: Well, it means that we haven’t learned yet that every music that we do today comes Africa. We like it or not, that’s just the simple fact and

truth of it.

It is true. Everywhere you turn, everywhere I turn as a musician, I’ve always find my continent especially in my country.

Blues comes from the songs of the slave. The blue note has been created by the Africans. I mean, jazz has been created by African descendants.

For me, music is just what we are, the mixture that we are from the beginning. As a human being, we are mixed. There’s no such thing as a

purist.

And I don’t understand white supremacy because supremacy has to be a higher level of morality, the highest in life.

It cannot be killing people. It cannot be hating people. Because you’re talking about supremacy and hate, those things don’t go together.

So for me, Africans that came here, the African-American didn’t migrate here like the Irish or any other people. They have been forced to come

here. They have created the wealth of this country and they have created the wealth of Europe. That’s slavery.

Today we don’t want to talk about it. We blame Africans for slavery. Of course, it comes as a business proposal to the king and they thought it was

going to be a good thing. The lie that have been told to them, they bite. They bought the lie.

And here we are today. But to make a long story short, I think we ought to always think about the fact that the genesis of the crime committed for the

rich country to cause is in the African people.

And that model of slavery is also implemented in business because we Africans are not free. They say we have independence. Which independence

are you talking about?

The raw material we have in our country. We don’t define the price of the raw material. The price of all these is decided by the leaders of Africa.

We have the wealth but the wealth is in the work in the hand of the westerners. We, of course, the help of our leaders that just really

fasting the job for them.

So for me as a musician, what I say to people is we, that come from that painful story, how do we create a different narrative? How do we show the

world that despite all the wrong that people have done to us, we are still human beings and we are still willing to create bonds.

We don’t have a choice. We cannot live without each other. It does not matter what skin color you have. We have to live together.

And it’s something that I learn every day, especially when as UNICEF ambassador, we go to the villages and we see all those kids suffering.

When you face a child soldier, when you face a teenager that has been constantly in conflict and you have no words to touch them and you start

singing and you see a smile. That’s the power of music.

And it’s something that makes me humble. It makes me come to the core of it and say as a human being, what do I have to bring to the table?

AMANPOUR: Well, what you brought to table is not just your music but very famously at this G7 that just happened in France, you were there and you

got all the countries to put hundreds of millions of dollars into a fund to pay it forward, so to speak, to help African female entrepreneurs. That

must have been pretty tough.

KIDJO: It was tough. It’s not easy to do, but I — when I met the women of the market in my country, half an hour into the meeting they were, they

were always falling asleep in the morning and I said how can I help? What are your issues? What is the problem?

And it’s not that I think it’s going to solve our problem. The women in the market, they said to me every time we take a loan, we spend all of our

energy to claim that loan. And when we finish, we find ourselves within two weeks that we need another loan because we don’t have enough money

aside to invest and diversify our business and to put money aside to send our kids to school.

That’s when I said we have to find a solution to that. So I spoke about this issue to the President Macron of France, and he asked me what is

needed? I said that’s where we can transform Africa.

The women of the market, every year around the continent, we miss $2.5 trillions that they’re produced that is nowhere to find. And what also

that touches me is that those women are the one whom children are dying.

You bring a child to this world, you try to raise them right, you try to give them a future. And everywhere around the world, everything that is

done, even though we send them to school telling them school, education is going to give you a future, ironic, all the decision taken around the world

is taking away their future.

And now they become political talking point in Europe for all those racist people that don’t understand that they are living the life they’re living

due to us living in poverty. And I think it’s about time we start thinking about how we share the wealth of this world.

AMANPOUR: So what keeps you optimistic?

KIDJO: The strength and the resilience of the people around the world, white, black, yellow, red, because poverty is in this country, too. I

think we need really to come to realize that if we’re not each other’s keeper, we lose everything.

There’s not another life out there. There’s not another ecosystem or this one on this earth. If we mess it up, rich, poor, yellow, black, whatever

color you call, whatever language you speak, mother nature don’t know that. When death comes knocking, (inaudible) billions, you’re gone.

AMANPOUR: On that note, Angelique Kidjo, thank you so much.

KIDJO: It’s always a pleasure to be with you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Anything optimistic you want to finish off?

KIDJO: Always. (Music)

AMANPOUR: That’s really good. It’s really good. It makes us wake up and feel happy and optimistic despite the serious issues that we have to deal

with. Angelique, thank you very much.

KIDJO: You’re welcome.

AMANPOUR: Our next guest wants us all to connect more. Mark Brackett is an emotional scientist, a Yale professor, and he thinks emotional

intelligence skills should be taught from an early age.

With mental health issues rising exponentially, his work has never been more pressing. And he spoke to our Michel Martin about his new book

“Permission to Feel” and how he spent years learning how to do just that.

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Marc Brackett, thank you so much for talking with us.

MARC BRACKETT, AUTHOR, PERMISSION TO FEEL: My pleasure.

MARTIN: The thing about this book that I like is that you make it sound so simple but it really isn’t. I guess I’ll start with the title which is

“Why do we need permission to feel?”

BRACKETT: You know, permission to feel is an important term for me because, as a child, I didn’t have that permission. I had a tough

childhood and nobody asked me to talk about my feelings. Nobody saw what was going on for me, even though it was pretty clear.

And so I chose that title because I felt people have to be given that permission. And especially adults who are raising kids and teachers who

are teaching kids, we need to create context where children have the permission to experience whole emotions and where they have that permission

to express them.

MARTIN: And you talk about it in the book, but do you mind sharing here what is it that lead to that lightbulb moment for you? How did you come to

understand how important it is to be given permission to feel?

BRACKETT: Well, as a child, I had an abuse situation. I also was bullied pretty horrifically.

And I was very unhappy and I was a poor student in school. And somehow I knew I was smart but I just couldn’t perform well academically.

I had two parents who loved me dearly, but my mom was a very anxious woman. So when I would even talk to her about my bullying, she would say, “Oh my

goodness, honey, don’t tell me, I’ll have a break down.”

And my father was also a great man but he was like, “Son, you’ve got to toughen up.” So I learned very quickly as a kid mom’s going to have a

breakdown if I tell her how I’m feeling and dad’s just going to keep on telling me to toughen up.

But there was some wizard that came into my life and his name was Uncle Marvin. And —

MARTIN: He really is your uncle?

BRACKETT: He really is my uncle. And he was an interesting character because he was a middle schoolteacher by day and a band leader at a

Catskill Mountain Hotel by night.

And Uncle Marvin was developing a program to teach kids about feelings through his social studies class. And he was getting a master’s degree

when I was in my middle school years.

I’ll just never forget, you know, one day he just said, you know, “How are you feeling?” And then he just paused and his facial expression, his body

language was so open. And I knew it was a time to just tell him how I felt which was angry, scared, the list goes on.

And then he just said, “Well, what can we do about it?” It wasn’t what can you do about it, it was what can we do about it?

And that to me, that was the first adult who heard me and the first adult who listened to me and was there with unconditional love and support.

MARTIN: I don’t want to glide past what you said, an abuse situation. I mean, this is a terrible situation.

You were abused. I hope this person was brought to justice, at some point, held accountable for his conscious —

BRACKETT: Well, I was the person responsible for that. And you would think that would be something positive, which it was, to some extent. But

unfortunately, growing up where I was in New Jersey in the 1980s when this happened, the block turned against our family.

Because we had, you know, the pedophile. And it was quite scary for me. Because parents were telling their kids not to play with me.

I was on public television, actually, when I was 11 years old talking about this, which just kind of a deja vu moment for me because I think it was

inappropriate for me to be on T.V. at 11 disclosing my abuse nationwide.

MARTIN: I’m sorry for that.

BRACKETT: Yes. Well, the ramification, you know, were that stay away from Marc. He’s damaged goods. But now, it’s 39 years later and look what I’m

getting to do.

MARTIN: The reason I was thinking about that, though, you know, forgive me, this isn’t when dinosaurs walked the earth. It’s not like people

didn’t understand that there was a language of feelings, that feelings matter, that the abuse of a child matters, that a kid should have an

opportunity to express themselves.

And I’m just curious, like why has it taken so long for people to understand that this matters?

BRACKETT: Because people, in general, see emotions and feelings as weak. Like a man having shame, a man feeling fear, right?

You know, it reminds recently when I was giving a presentation, a father who heard me speak about my childhood said I can’t believe how much you

talk about your childhood and your bullying. I would never let my son know I was bullied because he would think I was weak.

And, you know, it’s eye opening. And what I said to him was, well, what if your son is being bullied?

And you’re sending messages to him that say I’m not here to listen to you? What would that mean? How would that make you feel as a dad to your child?

MARTIN: One of the arguments that you make this isn’t just about abuse situations, as you put it. It’s about a skill that you think people need

to learn. Can you talk more about that?

BRACKETT: These are life skills. So, you know, yes, I had a traumatic childhood that led me to this path. I also wanted to just say that I feel

blessed that I had that uncle.

I got involved into martial arts which is a big part of my life. I made it in psychology. I went through therapy. I spent a lot of time giving

myself permission to feel.

But putting that aside for a moment, you know, just from life is saturated with emotion. The moment we wake up, you know, we think about our

workplace and we say do I want to go to work today? Do I not want to go to work today?

The commute. Meeting, one meeting, two meeting, three. Life is just filled with emotion.

And what we know from our research is that emotions drive five really big things. Our intention. So how we feel, drive for our brains, pay

attention.

The second is decision making. Think about that. How you feel influences your choices and your judgments from what you eat to, what you buy, to how

nice you are or not nice you are to somebody.

The third is the quality of our relationships. You know, how you feel, right. If you’re feeling down and depressed, you’re probably not going to

approach the world. But when you’re feeling inspired and connected, you’re going to want to move forward.

The fourth is mental health and physical health. And, finally, something that I think everyone should care about, which is performance in school and

working and creativity. So emotions are responsible behind almost everything we do in life.

MARTIN: I would make an argument that all those things are things that everybody should care about like relationships and social interactions and

things of that sort.

BRACKETT: Exactly, yes. And people don’t lose their jobs because of their abilities in the cognitive area usually. But it’s because of their

inability to regulate, right.

Think about your life in terms of the people who you like to work with and didn’t like to work with. Oftentimes, it’s the people who just don’t have

the skills to manage their feelings.

MARTIN: So where do you want us to start in thinking about this?

BRACKETT: Wow. I want us to start, I mean, maybe in utero. I’m serious, though.

How moms and dads experience the world affects, you know, the fetus. But truthfully, you know, my work is in schools and in workplaces.

So I believe that everyone deserves an emotion education. It needs to be part of the way we think about education from preschool to high school to

college to becoming a lawyer, doctor, teacher, whatever your profession is.

MARTIN: So you’re saying everybody deserves an emotion education.

BRACKETT: That’s correct.

MARTIN: OK. That’s carried into this idea of emotional intelligence.

BRACKETT: Right.

MARTIN: Could you just talk about what that is? I mean, this is a term that I think a lot of people have heard for quite some time.

BRACKETT: In fact.

MARTIN: But what is it exactly?

BRACKETT: We say emotional intelligence as a set of skills that help us to use our emotions wisely. So it starts off with recognizing emotions,

right.

Am I aware of how I’m feeling? Am I aware of how you’re feeling?

And then the question is, do I know where that feeling came from? Is it what I said? Is it what I did? Is it from a memory? What is causing my

feelings?

The third is, what is the exact feeling? What is the precise word?

For example, in the angry category. Am I peeved? Am I angry? Or am I enraged?

In the sad family. Am I down? Am I disappointed? Am I hopeless.

And in the happy family, am I content, or am I happy, or am I ecstatic?

That’s the first set of skills. We call it the RUL of ruler which helps us to make meaning out of our own and other people’s emotional lives. Then we

have the E and the R, which is expressing and regulating emotion.

It has to do with what we do with our feelings. So do I have the permission to be my authentic true self with you? Can I express my

feelings at home, at school, at work?

Now, do I know how to express them in a way that gets my needs met? That helps other people?

And then finally, I think the big, big one is regulation of emotion. So what are the strategies that I use to prevent unwanted feelings, to reduce

the difficult ones or even to create the ones that I don’t want to have in life?

MARTIN: People are very, I think, aware of wanting kids to regulate their emotions. I mean, that’s kind of what school is all about, right, sit

still, don’t throw your pencil at this other kid that made you mad and that kind of thing.

But I think what I hear you saying is that we’re very aware of wanting kids to regulate their emotions but we don’t tell them how to do it. Why is

that?

BRACKETT: Because the adults who are raising and teaching kids haven’t had an adequate emotional education. So, you know, think about that.

When we’re, you know, frustrated, calm down, sit down, be still. And that’s not being a great role model, right. You can’t yell at someone to

calm down. It doesn’t really make much sense.

And I think importantly what we also forget is that emotions are what we like to say, co-regulated. Think about this. In a classroom, in a home,

in a workplace, right, how as a manager, as a leader if I walk into my 15th in my center, if I walk into a meeting and be like, all right, we have to

write another grant. It’s going to bring, you know, it’s going to change the mood.

So emotions are co-regulated, right. We’re in relationships most of our day.

MARTIN: You know one of the things that has gotten a lot of attention in recent years is just how stressed out adolescents are. Kids, too. I mean

not just adolescents.

Some of the data in 2017 about eight percent of adolescents age 12 to 17, and 25 percent of young adults describe themselves as current users of

illicit drugs. The number of incidents of bullying and harassments in the United States in K through 12 schools, this is according to the Anti-

Defamation link, doubled each year between 2015 and 2017. Internationally, this is an issue. Apparently depression is the leading cause of disability

worldwide.

So do you feel that your area of study, emotional intelligence, is also a factor here in some of these issues we’re describing?

BRACKETT: I think it says why we need these skills more than ever. You know, and, you know, we don’t think of emotional intelligence being an

individual skill.

This is skill that is about, yes, the individual I need to regulate when I’m by myself in the airport and if I’m stressed out and overwhelmed. But

I also need these strategies with my partner, with my family, I need them at work.

And, you know, the truth is, that communities and organizations have feelings. So if you are a leader of a company — to give you an example, I

was at a big financial company here in New York City and one of the top executives, you know, he heard me speak and he’s like, you know, this is

kind of interesting but, you know, I don’t need this training.

So, what do you mean? He’s like “Look at me, I’m the boss. I can do whatever I want. But maybe I’ll have you train the people who work for me

because then they’ll have skills to deal with me.”

MARTIN: How do you respond to that? What he’s saying is true, right. He doesn’t care how he makes other people feel.

BRACKETT: He probably doesn’t. What he doesn’t realize is that the people who work for him are going to have feelings and how they feel is going to

drive their decision making, the quality of their work, how much time they spend on social media versus doing their work.

So maybe if he spent more time thinking about how people felt, actually the company would do even better than it’s doing.

MARTIN: OK. So maybe extend that a little further. Make the business case for why people should care.

BRACKETT: We did a national study in our center with 15,000 people across the workforce from people who work in farming to people who work in

finance. And what we found was that people who work for an emotionally intelligent, as opposed to an emotionally unintelligent supervisor have

different lives at work.

Just to give you one example, feeling inspiration, which is an important thing, probably to feel at work, there was a 50 percent difference in

organizations or for people, I should say, when they work for someone who has high versus low-end emotional intelligence.

Creativity was significantly different when you work for someone who has high-end emotional intelligence. Your burn out levels, your stress levels,

your intentions to leave your profession.

So turnover has a high cost to organizations. And so how you feel is determined by the leadership’s emotional intelligence, and there’s greater

turn over intentions, when a leader who is low in emotional intelligence, my hunch is that they should read my book and learn these skills because

it’s going to make a difference. / MARTIN: And what about kids? Kids can’t leave the institution by and large unless they really act out. I mean they’re kind of captured, right.

So talk about kids. Like why does it matter that kids learn these skills?

BRACKETT: Yes. Wow.

MARTIN: And the people teaching those kids.

BRACKETT: Because, you know, emotions are the drivers of kids’ attention in school. You know, people say things like we only learn what we care

about. So if we don’t infuse emotion in the learning process and create the engagement, students are going to get bored. They’re going to get

distracted.

That’s when bullying happens. That’s when students drift off into disengagement.

So I think, also, what you’re getting at is this idea of the climate of a classroom. So we’ve done research on that where we have literally

videotaped classrooms and looked at the interactions between teachers and students. And what we find is that classrooms where there are teachers who

are more emotionally skilled have students who are better learners, there’s less bullying, there is greater academic achievement.

MARTIN: Can you just give us a couple of tips about how you can start giving yourself permission to feel so you can be a more inspiring leader or

teacher or be a more inspired student?

BRACKETT: I think you’re saying it. The first thing that I talk about in my book is just giving yourself that permission, that recognize that

emotions matter, that they’re valuable sources of information.

Second thing is, as I talk about in the book, is the idea of being an emotion scientist versus an emotion judge. So for example, are you open to

the experience of all emotions? Are you open to other people’s feelings? Are you open to learning new strategies to help you be better managed, to

help you regulate feelings better?

The scientist is open. The judge said says “You know what, this is who I am, get over it.” So we’re trying to get people to be more like scientists

than judges.

And the third is recognize that this is a lifelong journey, that you’re not going to be perfect. And I think the big one is just practice regulating.

Like learn new strategies.

Most people — I didn’t know what they were until I was a graduate student. So for example, engaging in more positive sub talk than negative sub talk.

Catch yourself.

Like wait a minute, I’m like — the other day, for example, I was working out in the morning and I said, Marc, you’re going to be positive. And then

I was thinking, oh, my legs are so white. I trashed myself.

MARTIN: Oh, my goodness.

BRACKETT: Yes. And I was like wait a minute, Marc, like here’s — like that’s not helpful. It was like catch yourself when you’re doing the

negative talk and say, all right, how can I think about this in a different way? What is a different story that I can tell myself?

MARTIN: Marc Brackett, thank you so much for talking with us.

BRACKETT: My pleasure.

MARTIN: And how do you feel now?

BRACKETT: I feel relieved.

MARTIN: OK. Me too.

That’s it for tonight. Remember, you can always follow me, Michel, and the show on Twitter.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS, and join us again tomorrow night.

END