Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And as we said earlier, COVID cases in the U.S. crossed the 11 million mark over the weekend, reaching yet another grim milestone. And our next guest is in a unique position to understand the virus and its ripple effects on society. Nicholas Christakis is a physician, sociologist and a former hospice doctor. His latest book, “Apollo’s Arrow,” explores what it means to live amid a plague like this. Here he is speaking to our Hari Sreenivasan about all of this and about what he thinks President-Elect Biden must do to restore confidence in institutions.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, thanks. And Nicholas Christakis, welcome back. I mean, you were the first person that I spoke to from my bedroom studio when this all started in March. At the time, we were perhaps stunned to hear a prediction of 35,000 people who might be victims of COVID-19, and here we are now past 250,000 people in the United States that have died from this. Something that you say in this new book that you’ve written, “Apollo’s Arrow”, that right now where we are is the end of the beginning, not the beginning of the end. Explain that.

NICHOLAS A. CHRISTAKIS, AUTHOR, “APOLLO’S ARROW”: In other words — you know, we have had the first wave has struck us. The pathogen entered the human species in November and is spreading and spreading and doing what it does. Probably 12 percent of Americans have been infected so far, and in the end, probably 40 percent to 50 percent of Americans will be infected. And so, we’re just experiencing this event, this pandemic still. And as people know, we’re now at the beginning of the second wave, which is going to strike, unfortunately, with tremendous force. So — and there will be more waves incidentally. There will be a third wave in a year, and a vaccine will probably have been invented by then and reduce the amplitude of that wave, but this virus is going to be with us forever.

SREENIVASAN: Do the math for us, we’re at a rate of roughly 140,000 infections a day and if we have a 1 percent infection fatality rate, that means about 1,400 people that were, well, diagnosed or found out yesterday, are likely not to survive this. So, how bad does this get if we’re just in the second wave, and there are more waves that will inevitably come?

CHRISTAKIS: We have, as you said, about 250,000 Americans have died so far that we know of. But there’s this old technique called the excess mortality rate which was invented in the middle of the 19th century which looks at the total excess deaths of people during a time of pandemic compared to normal times. And by that metric, we have more deaths, maybe 300,000 more Americans have died in the last few months than would have died in previous years. So, the total burden of mortality is higher than 250,000, probably closer to 300,000 people have died because of COVID. And, as you said, about 1,000 or more per day are dying now, the sort of up ramp of the second wave. So, I think it’s pretty clear at least 500,000 will die before the end of this pandemic. Now, to be clear, that will take another couple of years and maybe as many as a million. So, that range of 500,000 to 1 million is probably where when the histories are written in 5 or 10 to 20 years, we will have wound up unfortunately. I should also say, while it’s completely appropriate that we focus on mortality, I also have to mention that many millions of Americans will have to disabled by this condition.

SREENIVASAN: We’ve had conversations on this program about people who are living with COVID for a very long time, months at that time. And so, what percent of the population, setting aside for a moment if it’s 500,000 to 1 million that might be filled (ph) by this, what percentage of the population are likely to be having long-term consequences? And what’s the ripple effect for us as a society, as a health care system?

CHRISTAKIS: So, there’s a distinction between people who have so-called long COVID, whose symptoms endure for a long time and take a long time to recover. They might have some mental problems, you know, so-called COVID fog, they might have ongoing respiratory problems and so on, but they might eventually completely recovery. There’s a difference between that category of people and the category of people for whom whether the disease was short or long in duration have some persistent disability. For example, a problem with their kidneys, renal insufficiency or some cardiac problems, or some neurologic problems or some persistent pulmonary fibrosis, for example. We don’t know what percentage that will be, it’s very difficult to know this, but many experts think it might be around 5 percent. So, we might lose, let’s say, 500,000 at least Americans will die at this, but we might then have 2.5 million who have some long-term disability. And some of my colleagues, former colleague at Harvard, Larry Summers, a former treasury secretary who is an economist and David Cutler who is a health economist there, recently published the paper that called this the $16 trillion virus. $8 trillion due to economic impact on our society and another $8 trillion due to the health impact, death, disability, and illness. These are vast sums. This is an enormous calamity that has befallen us. And I’m not sheer to doom say. I’m just here to try as much as possible to frame for listeners the reality of what we’re facing. Because I think that the sooner we accept this reality and the sooner the American people rise to this occasion with a sense of civic purpose and a sense of maturity and abandon a sense of wishful thinking, the better able we will be to band together to cope with and repel this virus that is threatening us.

SREENIVASAN: Getting from the global down to the personal, in the book you talk about your former life, if you will, as a hospice doctor, and you talk about how you have literally held the hands of so many people that have passed on at that moment when they were alone. That is probably one of the most heartbreaking effects of COVID, is to hear these stories and read these stories about loved ones who were separated at that last second. What can we do as a society now, nine months in, 10 months in, knowing what we know to at the very least give people that moment of dignity or peace?

CHRISTAKIS: Well, one of the things that’s so upsetting about plagues is that they are grief making. They are a time of grief and a time of loss. People lose their lives, they lose their livelihoods, they lose their way of life and many Americans are seeing this. Schools are closing. People are losing their jobs. We can’t go to dinner with our friends anymore. We can’t go to restaurants. It’s sad. I mean, this is — and this has happened, you know, in medieval times or in Ancient Greece, people talk about the same exact phenomenon that we are discussing. And similarly, one of the phenomena that they talk about is people dying alone. Because during the time of a contagious disease, at least in the past, people were afraid that they would contract the disease by caring for the decedent. And in fact, during the bubonic plague, you literally got it from dead bodies, as people were dying, the fleas that have transmitted the bubonic plague would leap from the person who have just died, the fleas could sense that the body was cold, they have an ability to sense warmth, and they would leap to the nearest warm body, which was the people caring for the person who had died, you know, cleaning their body and so on. So, we have centuries of descriptions of dying alone in times of plague. And it shocked me as a hospice doctor in 2020 in modern America where this had returned. Now, it returned for a number of very specific reasons, which we can as a rich society and as a scientifically grounded society, address. Believe it or not, one of the main reasons it returned was that we didn’t have enough PPE. In other words, we couldn’t spare the PPE for family members to come to the hospital to be with their loved one dying from COVID, which is appalling. I mean, just an appalling dereliction on the part of our leaders that we weren’t equipped to deal with this. To my eye, someone who’s dying, their loved ones should be there, that’s a priority, for them and for their loved ones. And I believe despite the burdens on health care system, our system should be organized to meet that important human need.

SREENIVASAN: You traced throughout this book how going backwards through time, there are almost these three distinct phases to pandemics like the one we’re in now. But break that’s those down for us.

CHRISTAKIS: OK. So, what’s happening now is we are in the biological and epidemiological phase of the pandemic. The virus was set loose in our species and we had no natural immunity to speak of or very limited natural immunity. We are very likely to invent a vaccine in the coming months, which is fantastic news, this is great news. Probably many vaccines will be invented. But once we invent a vaccine, we still have to manufacture it, distribute it and persuade people to take it. And that’s going to take time. Perhaps a year. So, from where I sit, 2022 is a landmark year, which I call the immediate pandemic period by which time we will have reached herd immunity either naturally or through vaccination. And what that means is from now until then, we’re going to be living in a changed world. Wearing masks, physical distancing, intermittent school closures, intermittent lockdowns, just as we’re seeing right now. But then, in 2022, we’ll cross into what I consider to be the intermediate period. So, the epidemiological and biological shock will be behind us but we’re still going to have to deal with the psychological social and economic sequelae of the virus. And that, judging from historical pandemics, will take a couple of years until our economy gets stood up again, people feel normal about going to airports and restaurants and so forth again, begin to take their masks off and so on. And then in 2024, we’ll reach what I consider to be the post pandemic period. Approximately. These are approximate figures. And that could be like the roaring ’20s after 1918. So, all the increase religiosity, you know, religion rises during times of plagues, the abstemiousness, the saving — you know, people are saving money now, people are avoiding risk. All of that will reverse. And so, people, I think, beginning around 2024 will relentlessly seek out social interactions. They’ll go to night clubs and restaurants and sporting events and political rallies. People will start spending liberally again. There will be a lot of risk taking. (INAUDIBLE) for example. Maybe some sexual licentiousness. Some people have read these descriptions and said, you know, here’s hoping, you know, that we — that that’s the world we will in. But the point is, there will be some kind of efflorescence, some kind of effervescence, I think, that begins around 2024.

SREENIVASAN: Right now there is a very strong contingent of people who say, we cannot afford to continue down this path, between now and 2024, the poverty that we are inflicting on our people by having this crushed economy is possibly worse than what the virus could do to us.

CHRISTAKIS: Well, we’re — just remember, only part of what’s happening to us is because we’re doing it to ourselves. The virus is the real enemy. The virus is doing this to us. The virus slows down economies. You know, we have descriptions from the plague of Justinian, 1,500 years ago, that talk about how everything slows and ceases. The world became still. This was before, you know, there were governments ordering people to stay home or closing schools. This was what virus — you know, pandemics do. What epidemics do. This is awful, but I don’t think willful denial helps us, right? And, you know, let’s remember that plague is one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. And if that’s the case, you can think of lies and denial as being the squire of the horseman, you know, following right behind. So, just as germs spread through social networks, since times immemorial, lies and denial have spread right behind it. And this is where I think leadership is so important and where I fault the Trump administration, which I think has fostered a culture of superstition, denial, even lies about the epidemic, pretending it’s not a big deal, pretending that hydroxychloroquine will be a miracle drug, when this was known to be false and on and on. And where I hope that President-Elect Biden will more capably lead us, because we need our leaders to be square with us in times of plague, because it’s so tempting to lie and deny.

SREENIVASAN: How does a President-Elect Biden renew faith in institutions? I mean, this past year and a half has shaken the confidence of millions of people in things like the CDC and the FDA, things we thought for bedrock reliable. People are now saying, well, I don’t know if I should take this vaccine that’s been approved by the FDA. Maybe I should wait for 1 million other people to be my guinea pigs.

CHRISTAKIS: Yes, that’s a serious concern. Now, it is true the CDC stumbled early on with the tests and there were some complicated bureaucratic interactions with the FDA, which sort of boring to go into. But we could have done better with the tests. But generally speaking, the CDC scientists know exactly what’s going on. So, to restore confidence, I think we’re going to need a number of communication strategies. And I should say as a nation we need to work together to tamp down on falsehood and to begin to hold our leaders to account for honesty and accuracy. So, how do we do that? I think it’s very important when leaders communicate in times of stress that they are honest good people, share the basis for their statements, here’s my evidence for why I’m saying this, and their degree of uncertainty. That way when you revise your opinion in a month and you say, actually, I had told you this, but now changing my mind. You explain why. You could say, I was only 50 percent sure back then. This was the evidence then, now we have new evidence. So, the ability to admit failure or wrongness is a very important part of maintaining credibility. And finally, willingness to break bad news and to say to people, during a time of a deadly contagion, there’s no life without risk. There’s no easy out. And I think here, the American people need to be called to service and called to sacrifice and called to common purpose.

SREENIVASAN: You’ve studied this. You’ve written about this, the idea that we fundamentally want to create good societies, that part of a good society is sacrificing for something greater than ourself. Do you see that happening right now, especially in the U.S.?

CHRISTAKIS: I do, actually. I mean, during times of epidemics, there’s a lot of badness that happens. There’s blaming other people, there’s denial and lies, there’s abandonment. We’ve discussed some of those things. But also, there are good things. People band together to work together. People are kind to each other. Doctors and health-care workers and first responders take personal risks. Some of them die as a result of trying to help other people. So, there’s a sense to which human beings are called not only by our sort of political or social desires to fight the virus but by our innate nature to work together, actually, to be kind to each other and care for each other when we’re sick. So, I see a lot of goodness in human beings and I see a lot of promise in our society in more effectively working together to invent technologies to fight the virus and to band together to implement the kinds of procedures we need, for some time, to survive this modern plague.

SREENIVASAN: So, why do you think there’s a portion of Americans who is don’t agree with the idea of sacrificing for the greater good when it comes to doing something like wearing a mask? Why is that a reality in this country versus how other countries have dealt with this in a very collective fashion?

CHRISTAKIS: Well, some countries, yes, have done better than others. But the desire to deny the reality of a plague is ever present. And, again, I think this is where the role of leadership comes in. The fact that human beings don’t wish to accept it, in some ways you can even make the argument that it’s the perfection of our democracy that allows us to have to leaders we deserve. So, if people want to be lied to, they will vote for leaders who will lie to them. And in a society in which the will of people is reflected effectively, then you get the leaders you deserve. But those aren’t good leaders actually. We can criticize those leaders and say, you know, they are not being truthful. Their duty is to be honest. So, I think everybody needs to rise occasion. The American people need to rise to the occasion, the leaders need to rise to the occasion, other officials need to rise to the occasion. And if you compare us to other countries, yes, some countries have done as poorly as us, but I don’t see the fact the other countries have done just as bad as us as an excuse. I see us as the United States of America. We have the CDC. We are a rich nation. We are supposedly able to deal with these things. And so, I held us to a higher standard. And I think we could have done better and I think we will do better.

SREENIVASAN: The book is called “Apollo’s Arrow.” Nicholas Christakis, thank you so much for joining us.

CHRISTAKIS: Thank you so much for having me, Hari.

About This Episode EXPAND

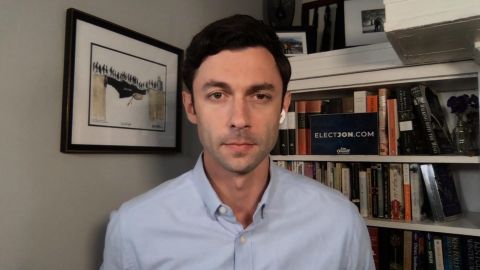

CNN senior medical correspondent Elizabeth Cohen reacts to today’s announcement that Moderna’s coronavirus vaccine is 94.5% effective. Walter Isaacson discusses his experience as a participant in Pfizer’s vaccine trial. Senate candidate Jon Ossoff (D-GA) discusses his race against Sen. David Perdue. Sociologist Nicholas A. Christakis discusses COVID-19’s ripple effect on society.

LEARN MORE