Read Transcript EXPAND

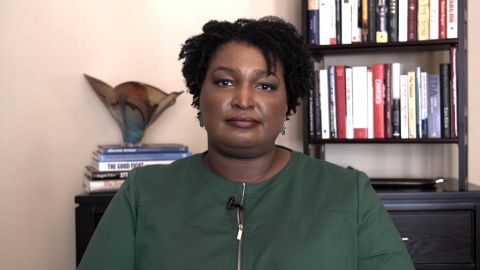

STACEY ABRAMS, PRODUCER, “ALL IN: THE FIGHT FOR DEMOCRACY”: With the evisceration of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, we saw the floodgates open. We saw 1,688 polling places shut down because they no longer had to get permission before removing them. We saw voter I.D. laws proliferate, making it harder and harder for people to meet these standards, making it stricter and more restrictive. And we have seen since that time opportunities for the right to vote be eviscerated because there’s no recourse, you can no longer go to court to protect yourself from state action to stop you from voting.

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Can you just give me an example of how repressive this is in terms of suppressing the vote. People might say, well, voter I.D.s, I mean, yes, sure, we all have to have a voter id. Give me an idea of the worst excesses that you say suppresses the vote today.

ABRAMS: So, voter I.D. laws. The United States has always required state- by state for you to prove who you are. But what has happened in the last decade has been that these standards, the bar has gotten higher and higher. The two best examples are that in the State of Texas, if you are a taxpayer that gets a gun license, you can use your gun license as I.D. to vote. But if you’re a taxpayer who goes to a school, goes to a state university, your student I.D., which is issued by the same government, is not valid. And the most precise case is that in Wisconsin in 2016, a black woman who had voted for more than 40 years who was born in segregation at the age of 100 was told she could not prove who she was sufficient to cast a ballot in the 2016 election because she was born during segregation and was legally not permitted to have an original birth certificate, but the State of Wisconsin required that she prove it, that she produce an original birth certificate, she could not produce because the law did not allow it.

AMANPOUR: I also — I mean, just things as simple as your signature. I saw in the film “All In,” that many, many immigrants obviously have to take American names. And over the years, their writing of that American name, which is not their original name, you know, changes. And their signatures don’t necessarily stay the same. That just seems so simple, and yet it’s so prescriptive for these people.

ABRAMS: Exactly. And that’s one of the most egregious and insidious parts of voter suppression. On its face, these things sound very logical. Yes, you should be able to prove who you are with I.D. Yes, you should be able to sign something to show who you are. But when you have citizens who may not have the training who are trying to guess whether your signature matches a document you may have signed a decade ago, that is unconscionable when you think about what it means for access to the fundamentals of democracy. As I point out, my signature doesn’t match when I’m going from grocery store to grocery store depending on whether I’m signing with a pen and a piece of paper or with that implement and that electronic pad, and yet, it’s being used as a reason to deny people the right to vote in a democracy.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane speaks with Stacey Abrams about Ruth Bader Ginsburg most famous dissent–against the decision to roll back major parts of the Voting Rights Act. She also speaks with Jeremy Farrar about the new coronavirus surge that has been steadily mounting in Europe. Walter Isaacson speaks with Doris Kearns Goodwin about the legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

LEARN MORE