Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, HOST: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

GEN. CHARLES Q. BROWN, AIR FORCE CHIEF OF STAFF: I just always wanted to be the best pilot I could be, the best officer I could be, the best dad I

could be, best husband. I just so happened to be African-American.

AMANPOUR: Air Force Chief of Staff General Charles Q. Brown joins me, the first black officer to lead a branch of the U.S. military. We discuss the

war in Ukraine, the rise of China, and the risk he took to address racial injustice.

Plus:

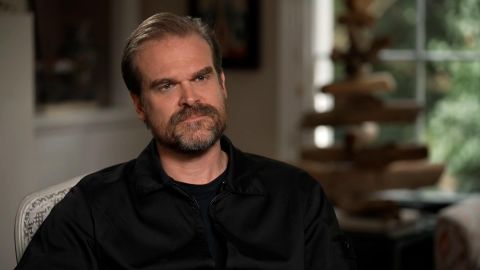

DAVID HARBOUR, ACTOR: I played so many losers and villains and people like that that I was happy for a leading man to have qualities that were very

broken.

AMANPOUR: Emmy nominee David Harbour tells me about going from “Stranger Things” to the “Mad House” in his new play.

Then:

HELEN ZIA, AUTHOR, “LAST BOAT OUT OF SHANGHAI”: This is an issue for all society. It’s not just an Asian American problem. This is an American

issue.

AMANPOUR: Activist Helen Zia talks to Hari Sreenivasan about an infamous anti-Asian hate crime from the 1980s and the chilling parallels to now.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

America’s best days lie ahead. That’s the message from President Biden. But many Americans don’t seem to agree. A staggering 85 percent say the country

is headed in the wrong direction, amid constant mass shootings, the cost of living crisis, the erosion of rights and ongoing threats to democracy.

Abroad, its key ally Britain is in turmoil. China is growing ever more ambitious. And Ukraine depends on the United States to help defend the

world order. President Zelenskyy is praising Western-supplied weapons as working very powerfully. But it’s clear he needs more, especially fighter

aircraft.

The importance of winning the skies has been largely overlooked. So, tonight, we turn to an expert. General Charles Q. Brown Jr. is chief of

staff for the United States Air Force. He’s the first black officer to lead a branch of the military. And now he’s focused on reforming the

institution.

I started by asking him about Ukraine when he joined me from the Pentagon.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: General Brown, welcome to the program.

BROWN: Well, thank you, Christiane. It’s a real pleasure to join you today.

AMANPOUR: Because you’re an airman, do you agree with those who would say, particularly those on the ground in Ukraine — and I have spoken to the

head of the defense intelligence and others there when I was there — that what they really need is fighter aircraft, that, yes, they have had an

amazing sort of the little engine that could success in the air, but they need combat aircraft to take out Russian air and also to take out Russian

positions, particularly in the east, as this battle now looks like it’s sunk into pretty much a slow, but sure Russian victory?

BROWN: What I will tell you, Christiane, is the Ukrainians have been very effective with the fighter aircraft they do have, with the surface-to-air

missile systems that they have, and how they have been able to operate.

In order to have additional fighter aircraft — and realizing that’s an ask from the Ukrainians — that takes training. It takes time to do that. And

so what we have been really focused on is, how do we help them in the immediate to ensure the long-term success of Ukraine?

And this is something that we will be focused on as a — not only as U.S., but as NATO, not just today, but I would say well into the future.

AMANPOUR: Do you believe that is being ramped up fast enough and effectively enough? And what do you see as the timetable? The president of

Ukraine has said he wants this war over by the end of the year.

For everybody in the world, this needs to end for every reason in the world sooner, rather than later. And yet the Russians are playing the long game,

as they do. What do you think in terms of strategy and endgame?

BROWN: I look at the long term.

And there are waypoints in that long term, and ideally is the cessation of hostilities. And the sooner we can get that to — it makes it more secure

for Europe. It makes it more secure for the Ukrainian population. And they have taken quite a beating over the course of the past several months.

But, at the same time, I also believe, even if hostilities stop, the tension that is already built up by the Russians with Ukraine and with NATO

doesn’t go away. And it’s something that we, collectively, as — particularly for the military — and you look at national security and NATO

security, it’ll be something that we’re going to be focused on for an extended period of time.

And I just — I will tell you this, based on my many years of experience. You never really get to an end state. You get to a waypoint. And you have

still got to continue to pay attention for the long term.

AMANPOUR: So, another long-term challenge — and, certainly, NATO addressed it for the first time in this summit, and I know that you’re also working

on this — is China.

They actually mentioned China as a strategic challenge. They haven’t in the past in their strategic doctrines. But they have now. And, as we know, U.S.

administrations famously talk about pivoting to China and trying to deal with it. You’re trying to help, reform, whatever word you use, the U.S. Air

Force to meet the challenge in the Pacific by China.

Tell us about that.

BROWN: Well, sure.

And, in part, this is based on, again, my experience. Before I became the chief of staff of the Air Force almost two years ago, I was the commander

of Pacific Air Forces. And I’d already spent a little bit of time in the Indo-Pacific with two assignments to Korea.

But I really started to think about what we have not been paying attention to as closely within the Indo-Pacific. And because of that, one of the

things I have tried to do as I have come into my position — I wrote my strategic approach, accelerate change or lose, because I knew some things

we needed to change.

At the same time, one of the action orders I have is on competition, and that action order is really focused on, how do we better and deepen our

understanding of the geostrategic environment, particularly in the Indo- Pacific and with the People’s Republic of China as our basic challenge?

And so that’s been my focus area as the chief. And, really, it’s really raising our awareness, understanding the threat, understanding the impact,

and not only how we as a military participate in our national security, but it’s all other parts of our interagency, with our allies and partners, and

how all that comes together.

So it’s really a — it’s a campaign of learning, is what I would call it. And it’s something that we’re going to continue on as long as I sit here as

the chief. But I think, ideally, we will continue that well after I’m gone as well.

AMANPOUR: You know, you just used a specific term. I think you said, accelerate change or lose. And I think that’s really a mind concentrator,

the concept of a possible loss.

So what is — can you give us a specific of how you intend to be more successful currently than I guess previous administrations, all of which

have said they want to meet the challenge from China, who seem simply to get getting stronger and more dominant?

BROWN: Well, part of this is, we — you think about what’s happened for the United States and the United States military.

We have been focused in the Middle East for the past, some people say 20 years, but, for the United States Air Force, I would say over 30 years,

going back to Desert Storm. And because of that, then we have really got to start changing our focus to, what is our long-term-facing challenge?

And if we are — don’t pay attention or let this happen very insidiously, then my concern is, we will wake up one day and be in a position where

we’re not in the position we want to be in, and there is potential to lose. And that’s a real possibility.

But we — I mean, that’s my focus as the chief of staff, to make sure we’re organized, trained and equipped, along with our joint partners here in the

United States military and with our allies and partners, that we focus on that threat, so we can preserve the rules-based international order that we

have all known well since the end of World War II.

AMANPOUR: A big challenge indeed.

Can I ask you to talk now a little bit about your own experience and the experience particularly in the U.S. military writ large, and particularly

on diversity?

So let me just read you a few stats. So you are the Air Force chief of staff, as you said, for the last couple of years, the first black officer

to lead that — or a branch of the U.S. military. But, last year, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Mark Milley, said the military is 20 percent

black, but only two of 41 four-star generals and admirals are black.

He also said that, when you were, in fact, commissioned as a second lieutenant — that was back in 1984 — only 2 percent of the Air Force

pilots were black, which is the same as it is now. What is the problem? Is it just blockages in the elevation of blacks? Or is it a problem with

recruiting more blacks into the Air Force and into the military in general? What is the obstacle?

BROWN: Well, one of the things I believe and I will say from my own experience is, young people only aspire to be what they what they see.

And one of the goals here is actually, how do we get more African-Americans in a position of leadership, in positions of aviation? And that’s one of

the challenge. And I will tell you, that’s — I was going to be an engineer. I came into the Air Force to be an engineer. That was my original

plan.

I got a chance to fly in an aircraft when I was in ROTC when I was in college, and that really changed my mind value. Now I need to tell you I

wanted to become a pilot. And that’s what I have been able to do for the past 37-plus years.

These are the kinds of things that we, as an Air Force, are looking, how do we engage with different diverse communities based on race and gender in

particular, and expose them to these opportunities in aviation?

AMANPOUR: I do want to ask you again about your own experience and what you said a week before your confirmation. It did go a little bit viral. It came

during the protests over George Floyd’s death, which was, as we know, two years ago.

And it was very intense. This is what you said:

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BROWN: I’m thinking about a history of racial issues and my own experiences that didn’t always sing of liberty and equality.

I’m thinking about my Air Force career, where I was often the only African- American in my squadron or, as a senior officer, the only African-American in the room. I’m thinking about wearing the same flight suit with the same

wings on my chest as my peers and then being questioned by another military member: “Are you a pilot?”

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Honestly, when I heard you say that, being questioned, “Are you a pilot?” it really — I mean, it’s so effective, the way you put that.

You took a bit of a risk. I mean, you posted a video. It’s not like you were in a public Q&A. You decided to go out and say that, and I think it

had to do with some questions from your own son. Tell us about that. What prompted that video?

BROWN: Well, our son was living here in Washington, D.C., and we were out in Hawaii at the time.

And his freshman year of college was the events at Ferguson, Missouri, which is about two miles from where he went to school in Washington

University in St. Louis. And he called us on a Sunday, and he was struggling.

And so, in our conversation, what he asked is: “Dad, what is PACAF, or Pacific Air Forces, going to say?”

And what he was really asking me is: “Dad, what are you going to say?”

And so I was waiting for my confirmation. And after thinking it over a little bit, I felt it was important for me to say something, because I know

people were looking for me, as a senior African-American officer, what was I thinking about? And so the video basically laid out exactly the things I

was thinking about, not just during this piece, but really reflecting on my career.

And the video that you just showed kind of highlights some of the things that have happened to me throughout my career, but not just to me, but I

would say there’s many of diverse backgrounds that, for various reasons, are put in situations where they don’t get the full opportunity or you get

discounted because you’re the first one that someone’s seen.

It’s those kinds of things. And the goal for me was, I just always wanted to be the best pilot I could be, the best officer I could be, the best dad,

I could be, best husband. I just so happened to be African-American.

And that to me is — I want to be judged on my merit, not based on the color of my skin.

AMANPOUR: And, briefly, what was the reaction from African-Americans or from white colleagues or just the general public?

BROWN: It’s been, I’d say much — overwhelming, probably much more so than I ever expected, because I had really wanted to focus the video to the

airmen of PACAF, and then it went viral, and it went much further than I ever expected.

Even today, I still get people to come up to me that I’d haven’t interacted with that how impactful it was, or they showed it at their place of

employment, or they shared it with a family member. And I’m proud that I did it in hindsight. I’m glad it’s having the impact it did. But that was

not never my intent.

And so it’s somewhat humbling, to be honest with you, just partly because I’m an introvert. So, for me to do something like that and get that much

attention is — it puts a little extra pressure on me that makes me maybe a little uncomfortable sometimes.

But I’m glad I was able to say something that I think was on the mind of many, many others.

AMANPOUR: Indeed.

And let’s not forget that your father and your grandfather both served in the Army, your grandfather in World War II in the Pacific, in fact. And I

just wonder. That history, obviously, is part of your history. And you must really think about that and how things have changed, even though not

enough, as you lay out in that video and as I quoted from Mark Milley about the numbers and percentages of four-star generals.

But how do you assess how far the military has come in terms of diversity since your grandfather and your father’s time?

BROWN: Well, I think the U.S. military here in the United States has really in some cases set the pathway for various things, and as far making

progress, particularly when you start talking about diversity.

And I will just — I’m — as you might imagine, I’m a huge fan of the Tuskegee Airmen. I have got quite a bit of memorabilia in my office. I have

always enjoyed meeting with the members of the Tuskegee Airmen.

But you think about what they did during World War II and the fact that, in 1948, President Truman then integrated the services. And I think about that

part. But I also think about my dad and his brother. You talk about me being early and first, but my dad was the second Army officer commissioned

out of St. Mary’s University in San Antonio. His brother was the first. His brother’s about 18 months older than he is.

And so it’s those kinds of things that — I don’t know if it’s divine, but it’s the aspect that, for our family, which I value immensely, has set the

pathway to allow me to have this opportunity and gave me the great foundation, so I could be sitting in this chair today as the Air Force

chief of staff.

AMANPOUR: So all of this really is about defending America, defending democracy and, as you said, defending our values.

Biden, the president, said that America’s best days still lie ahead. But, General, you have seen and we have just seen again on Independence Day a

mass shooting, this time in Illinois. We have seen the rollback of women’s rights, voting rights. We know that there’s runaway inflation, et cetera,

and a big threat to American democracy, which is being investigated on Capitol Hill, the January 6 incident.

I guess I want to ask you, are you sure that what you have been fighting for will continue to exist? And are the best days ahead? Or are they passed

and long gone?

BROWN: No, I think they are.

And I will just tell you, there’s a couple things that make me believe that when I look at America. I am a huge fan of President Lincoln. And you think

about from the time — you go back to when the election was back then in November and then the inauguration wasn’t until March.

From the time President Lincoln was elected until he got inaugurated, seven states seceded from the union. And we were able to get through that. I

think about the civil rights movement and the challenges there and where we are today.

And that’s just — when you look at democracy, yes, there will be some friction points. But, by and large, the values that we stand for, the

Constitution of the United States that I have taken an oath to support and defend has value. And it’s one of those things that it’s really to an

ideal, not to an institution, not to an individual, not to a symbol, but to an ideal.

AMANPOUR: General Brown, thank you so much for joining us.

BROWN: Christiane, it’s been my pleasure. And I look forward to meeting you in person one day. And thank you for the opportunity to spend some time

with you today.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And now from the challenges of this world to someone fighting evil in an alternate reality, our next guest plays the heroic police chief

from Netflix’s record-breaking series “Stranger Things.”

And David Harbour is also currently starring in the U.K.’s West End in the play “Mad House.”

We talked fame, mental health, and what’s next when we met here in London.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: David Harbour, welcome to the program.

HARBOUR: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: Did you ever think that “Stranger Things” would become the cult hit that it’s become, the pop culture phenomenon?

HARBOUR: No, not at all.

I mean, I read the script back in, what was it, 2015. And I remember thinking it was a very beautiful script, and I loved it. But I have been a

part of a bunch of things that I thought was really good, that people would really enjoy, and they have bombed throughout the years.

So I thought this would be another string of things that I thought was beautiful, but that no one would watch

AMANPOUR: And what do you account for the — for that not being true?

HARBOUR: I really just think it’s the sophistication of the storytellers themselves. Like, I think Matt and Ross are just really good storytellers.

People try to quantify it. They’re like, is it about the ’80s? Is it nostalgia? Like, what is it?

I really think it’s just good storytelling, I think it could be about anything, really.

AMANPOUR: And your character, Jim Hopper…

HARBOUR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: … describe him.

HARBOUR: Well, I mean, he is a throwback trope to these ’80s leading men, like — I guess like Harrison Ford in the “Indiana Jones” movies or like

Nick Nolte in these old cop movies, even like Gene Hackman, Roy Scheider, sort of these guys that I grew up with in the ’80s.

He’s a small-town cop in Hawkins, Indiana, which is a fake place. Indiana is a real place, but Hawkins is not. So he’s a small-town cop who has moved

back after he had sort of a life in the city and he had this tragedy happened where his daughter died. And he moved back to his hometown, and

he’s policing there. But nothing really happens until the beginning of the first season, where a big government conspiracy unfolds, where there’s kids

being experimented on, and monsters and all kinds of stuff.

AMANPOUR: We’re stunned, actually, here in England that the Kate Bush hit has been has been such an amazing thing, because she was so famous for

“Wuthering Heights,” the whole Heathcliff thing, and she’s also stunned that “Stranger Things” has given her song a new life, number one.

HARBOUR: I know. Yes. Yes.

I mean, I’m not surprised. I loved that Kate Bush song when it originally came around in the ’80s. But I’m not surprised that a lot of things — one

of the interesting things about the show is that we get to have nostalgia for these things, but the new generation gets to view it in a whole new

light.

But they still love it in an interesting way. Like, the no cell phones, kids on bikes riding around the neighborhood, that sort of freedom, that

sort of breadth that the series has, I find that a lot of kids who are 10, 11 12 really love that as well.

So I’m not surprised that there are these things that are wonderful about the ’80s that they’re — people are really appreciating. But it’s always

nice that an artist gets re-recognized in that way.

AMANPOUR: So let’s talk a little bit about that, the intergenerational thing and the throwback thing.

I mean, the fact is that you are a father figure.

HARBOUR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You — yes, the star Millie.

I have heard you talk about it being a little bit touchy in these current sort of climates, that you feel paternalistic to her, obviously, on screen,

but also off screen. You want to help guide and to the other young people.

And yet, because of all the issues, the social issues, there’s a certain reticence, a certain inability maybe to have done what you might have done

as a sort of a mentor in years past. Is that right?

HARBOUR: I would say that’s accurate.

I mean, I just think it’s more — it’s not so much the society. It’s more the fact that it’s not my world anymore. I mean, the world that I

understood and the world that I came up in and what I wanted to be when I was 14 years old was, I wanted to be an actor, a la Gene Hackman, Roy

Scheider, like guys that made movies, played different characters, did different things, were part of telling stories.

And now I feel like there’s an entire world of branding and this sort of mesh of celebrity and actor, which is a whole different world than I grew

up in. So I have no expertise in it. And I think that I have often felt like, as narcissistic as I am, I have often felt that my path is the path.

And I guess, as I go further with these kids, I start to realize that it’s not, and that I have to, like, let go of these ideas that I thought make a

good career or a good life. And so I have done my best to try to guide as well as I can and then to say, like, hands off, in terms of, this is a new

world that is your world. And you have to define it for yourselves.

AMANPOUR: And isn’t part of that new world the fact that kids not just in this program, but in many others — and there are a lot of child actors out

there right now, young adults — they are potentially having a pretty tricky, maybe even slightly dangerous experience with early fame?

HARBOUR: I, mean, I would say that’s true, I would say it’s a very tricky thing to navigate for anyone.

I mean, I was lucky it didn’t happen to me until I was 40. And so I had a true experience of life and being able to go to the grocery store and make

myself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, I mean, things like that. So, developmentally, to have that amount of attention and that amount of need,

like, people really do need something from you, and that — I think it’s somewhat unfair to do to a child, not that it’s anyone’s fault.

I mean, it’s like, these are great performances. But I even said early on to the press when we were kind of in the zeitgeist of awards and stuff, I

was like, I wish you guys could just let them be brilliant and, like, leave them alone and not pay any attention to them, and not even give them a

compliments, so that they can grow and learn and fail and risk and do all these things that I was allowed to do, because I think fame is in certain

ways a prison.

Because you do become a brand and you become something where people want something from you. And if you can’t deliver, if you risk and you fail,

then it’s detrimental to your brand. And I would hate to — I hate to feel that way at 45, but I would really hate to feel that way at, like, 13.

AMANPOUR: Would you say Jim Hopper, the character, is your first mega, mega fame?

HARBOUR: Oh, hell yes.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: And I have heard you say that yes, you wanted a Hollywood career, but you sort of found yourself always in supporting roles.

HARBOUR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Tell me about that. Why did you make your fame in TV and not in the Hollywood path that you thought you wanted to be, Gene Hackman,

Harrison Ford?

HARBOUR: I mean, that’s a great question. I don’t know that it was available.

I mean, I didn’t certainly didn’t think it was available to me at that time. I grew up — the funny thing about being photogenic even, where I

always thought I was very ugly on film — I was always a theater kid. And I would see — there are people that you take snapshots of them and they

always look great. And snapshots of me, I was always like the guy that looked like — I thought I would just never really have a career on screen.

And so I think part of my battle with myself has been that confidence to sort of take the lead role in that way. And I didn’t — I wasn’t able to do

it until I was ready to do it. So I was. I was a supporting guy. I sort of call it six or seven on the call sheet for like a solid 15 years.

You’re just — you’re the guy chasing after Denzel with a gun, and you’re telling him to stop or whatever.

(LAUGHTER)

HARBOUR: And so…

AMANPOUR: So you have had your brushes with all the big…

HARBOUR: Oh, yes.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Yes.

HARBOUR: And, in fact, I mean, that was part of the great thing was like I learned a lot from — you work with Liam Neeson, or Denzel Washington, or

all these legendary guys.

And I would just study them from the — sit in my chair next to him, try to talk to them a little bit, and then just study their work.

AMANPOUR: Maybe that’s really grounding?

HARBOUR: Yes. And, also, you know what it does too, is it — because I played so many other different roles, like villains and stuff like that, I

think, if you’re leading man when you’re like 22, I think you would tend to find things in characters that are romantic because of that particular

thing you want to sell of yourself.

And I think I played so many losers and villains and people like that, that I was happy for leading man to have qualities that were very broken and

human and messed up and maybe not so well-intentioned. And I think that allowed certainly Hopper in that first season to have a lot more complexity

than perhaps someone who would have come in and played him more romantically.

AMANPOUR: And a lot of empathy.

HARBOUR: Yes, I think so.

AMANPOUR: So you obviously lead me straight into the play you are performing in here, but also into your own life and history.

The play that you are performing in London is called “Mad House.” And you also have had your history of madhouse, personal.

HARBOUR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So talk to me a little bit about that. How does the play — how does the art imitate life, or vice versa?

HARBOUR: Well, it’s — Theresa Rebeck, who’s the author of this play, we had — she had wanted me to do a play of hers years ago. I couldn’t do it.

But I always admired her as a writer. She’s written some wonderful plays.

And so, before the pandemic, people had asked me, now with this sort of newfound fame with “Stranger Things,” they were like, oh, you should come

back to the theater because I have always been a theater actor my whole career. And so I didn’t want to do — I mean, initially, I thought, I will

play Coriolanus or whatever.

But I was like, we got enough Coriolanuses. Let’s do something new. And let’s talk about something that I want to talk about. And let’s open a

conversation.

And so she had this idea about a patriarch, a sort of Dostoevsky patriarch who was horrible and hospice care. And I had always wanted to talk about

what society calls mental illness. And one of the interesting things is, a lot of times when things come up in our society, we keep using this phrase

where we want to talk — we want to have a dialogue about mental illness.

We want to open a conversation about mental illness. And so, in that way, I wanted to have my dialogue with it. And the best way I thought I could do

it would be in long — certainly in long form, which is like a two-and-a- half-hour play, and to really show an uncompromising view and a nonsentimental view of what we brand mental illness is not something who is

a victim or a victimizer, not someone who is easy or difficult, but is both.

And so she started writing this play. And I had talked to her about some of my experiences, and she didn’t use those experiences, but she used the sort

of thrust behind those experiences.

AMANPOUR: Because you had been diagnosed with bipolar.

HARBOUR: Yes, when I was 26, I was institutionalized and diagnosed with bipolar, yes.

AMANPOUR: And, for you, I wonder whether finally knowing what it was, finally being diagnosed and treated, presumably, did it affect your acting?

Did it make you more empathetic?

HARBOUR: You know, I had been through the wringer with it for about 17 years in terms of trying different things, and going through different

phases.

I mean, a lot of these medications that they put you on are real baseball bats. There’s a lot of antipsychotics out there that are sort of cudgels of

— like, they just beat the hell out of your brain and sort of slow you down tremendously.

So I have struggled with what it is even. And then really what solved it, has solved it for me has been talk therapy. It’s a lot longer process. It’s

a lot more difficult process. But I found that understanding the true nature of the trauma or the narrative that you carry around is much better

than sort of the short-term Band-Aid of a medical way of dealing with it, which is what I had been back and forth on.

AMANPOUR: Do you feel, as I said, it is worthy, a much larger discussion.

HARBOUR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: We will have it. But I want to know whether you feel the need to be, or the burden to be or, just being an ambassador for this?

HARBOUR: A — I’m —

AMANPOUR: Because of your public —

HARBOUR: I mean, it’s interesting. I’ve been — I’m more the fox in the henhouse, I think, in terms of, like, I don’t know that I’ll be a good

ambassador. Because I have questions, you know. And my questions are large. They’re about the whole idea of what it is to be mentally ill because I

think there are larger discussions around, you know — and I think there’s larger societal discussions around the pathologizing of normal that I think

this is very difficult.

Because I think more and more, we are trying to pathologize normal as a result of, sort of, speed or fluidity and society. And I, sort of, think

that we should slow down and let people be weirdos. And kind of let people — I mean, I’m a little bit nuts. But I like — I miss the people the East

Village are screaming in the streets. And I miss the non-celerity of the cell phone world. And I miss a slowing down in general.

So, you know, the idea that we have — we, sort of, brand those people as mentally ill. And then we have people who, you know, work for fossil fuel

companies and make tons of money and who know that the Earth will be an uninhabitable place in 20 years as a result of the emission fuel. But if

they kiss their kids and make a paycheck, they’re very sane individuals.

And so, I think there’s a power dynamic at play in this particular idea in society. And I would like to see some of that shift. But I think the

biggest thing would be, in terms of any mental health initiatives or ambassadors, I do think that if you’re going to talk about it — I mean, I

was very happy that you have me on. You still have some crazy people talking about it and you still have some crazy people —

AMANPOUR: We’ll have you invite someone for us.

HARBOUR: I think you should have them, sort of, on the commission. Sort of, defining what it is that the mental health community needs —

AMANPOUR: Yes, for sure.

HARBOUR: — as opposed to experts, you know.

AMANPOUR: This also leads me into some of the things you said publicly since you started your, you know, stratospheric period of your career. And

you won an award back in 2017, the SAG Award, of course, with the “Stranger Things” cast. You said this about your craft.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARBOUR: This award from you, who take your craft seriously and earnestly believe, like me, that great acting can change the world, is a call to arms

for our fellow craftsmen and women to go deeper. And through our art to battle against fears, still centeredness, and exclusivity of our

predominantly narcissistic culture. And through our craft to cultivate a more empathetic and understanding society by revealing intimate truths.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: You’ve talked about being empathetic and less narcissistic in terms of mental illness and other things. But what do you mean by art in

your craft being able to do that? And that call to arms that you issued there?

HARBOUR: That’s a hard question. Wow. I mean —

AMANPOUR: What were you saying there? Go back to that moment.

HARBOUR: Well, I guess, you know, I’ve felt excluded from the Hollywood — weird thing to define. But I felt excluded because people have felt too

heroic, too pretty. And so, what I really appreciated on screen, and what I tried to do with Hopper was to make him ordinary and then to reveal the

extraordinary through the ordinary.

But I think that when I talk about narcissism in our industry, which is what? It was an industry night. It was a Street Actors Guild. So, I was

trying to talk about letting go of this narcissism and really allowing people entrance into our stories through the ordinary so that we can reveal

that they themselves can become extraordinary. Because one of the things that I think we’re seeing, and we see through various periods through

history is that, you know, we’re in a period where we want romantic, heroic, great looking people to look up on screen and to admire. And I miss

the Walter Mathau’s of Pelham — “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three” where it’s like —

AMANPOUR: Slightly quirky.

HARBOUR: — the sloppy guy —

AMANPOUR: Yes.

HARBOUR: — who’s able to overcome great obstacles because I identify with that guy. When you get to, like, you know, the big heroic muscular guys, I

just — I mean, view them as beautiful objects. But again, it becomes an objectifying thing as opposed to something that I can relate to and

something that my heart can be a part of.

So, yes, you know, I sort of want — I think, as an actor, I was really speaking to actors. I feel like it’s across the board though. The more

earnestly we work to tell stories and the more true they are. I think, like, violence, we can resonate and touch people and then those people can

touch the world and do great things.

But that’s sort of the lot that I’ve chosen or has been chosen for me, in a sense. And I just want to play it as well-intentioned and as broadly

intentioned as I can.

AMANPOUR: What do you see next for yourself, David Harbour, after “Stranger Things”? I mean, I don’t know how many seasons it’s going to be but —

HARBOUR: We got one more.

AMANPOUR: One more.

HARBOUR: We got one more.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

HARBOUR: You know, I have some fun stuff on the horizon. I have some silly stuff because I definitely believe in silly — you know, I talk here all

nobly and all but — you know. And then you’re going to see my next movie is about like a Santa Claus who’s, like, crazy.

So, anyway, I am a silly person. But also, you know, I have a lot of stuff that I’m working on now in development. And I say, I mean, the guiding

principle is what I said there, which is to expand peoples’ empathy. And hopefully the — you know, through this storytelling to have people realize

that society can be a little bigger. And in that way also, like, it aligns with mental illness that maybe we can accommodate a society with not-so-

normal people. With people — and that we can broaden our hearts where we are a little inconvenienced. But that — those people don’t have to go to

those extremes. They can feel a part of something.

AMANPOUR: That’s a really valuable mission. David Harbour, thank you very much.

HARBOUR: Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: That poignant call for empathy is needed now as vulnerable groups become targets of hate and discrimination. In the United States, attacks

against Asian-Americans are on the rise. Many are thinking back to the 1980s and the gruesome killing of Vincent Chin in Detroit. Helen Zia was on

the front lines as an activist then and she still leads the fight today. She’s joining Hari Sreenivasan to discuss Chin’s story, and the challenges

facing her community.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN, CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Helen Zia, thanks so much for joining us.

For those who don’t remember what the story was, it just passed the 40th anniversary of the murder of Vincent Chin. And there was a documentary the

PBS also played. But if people have missed that, if you could just bring us up to speed. What happened?

ZIA: It’s incredible to think that 40 years ago there was another time of intense anti-Asian hate, even though back then it was directed towards

Japan. And there was a young Chinese-American man, 27-year-old Vincent Chin, who was out celebrating his all-American bachelor party. And two

white autoworkers looked at him as he celebrated and said, it’s because of you mother effs that were out of work. And then proceeded to stalk him

through the city and eventually found him, and beat him to death with a baseball bat.

And that would have been terrible enough. But when it finally came down to sentencing, they received probation for killing an Asian-American. And that

triggered an Asian-American civil rights movement because it was as though we were reliving the 1800′ all over again. When you could kill an Asian and

get off scot-free for $1.

And so, that not only launched a civil rights movement for Asian-Americans but also was really a very broad-based movement that had solidarity with

people from all walks of life. Asian, black, Arab-American, brown, every religion that was present in Detroit.

SREENIVASAN: What happened to Vincent Chin, happened in an era pre-hate crime laws. I think a lot of this generation, or at least people growing up

today, take for granted that there was a time, in the not-so-distant past, where there was no protection from anything such as a hate crime.

ZIA: There were, in fact, liberal constitutional law professors who said, you know, Asian-Americans were not in America when these civil rights laws

were created. Therefore, if the Asian-American people, including other immigrants, should not be protected by federal law. And that was something

that our fledgling Asian-American community, as well as our civil rights allies, had to fight.

We really had to argue that, no. This was something that Vincent Chin would have been alive today. He’d be 67 years old today had he not had an Asian

face. And so, fortunately, the federal government listened to our, you know, arguments and undertook a federal civil rights investigation. Had we

not won, it would have taken a very narrow view of the law. And we would not have the 2010 hate crimes law that President Obama signed into law. So,

that was something that was hard-fought. And the contribution that Asian- Americans made to all Americans.

SREENIVASAN: Put us in context for what was happening in Detroit 40 years ago. And I also want to bring up to our audience, that at one point, you

worked on a car plant. I mean, you worked on the manufacturing line. So, what was that culture? And what was the problem with Vincent Chin, or his

Japanese counterpart, so to speak, with these autoworkers?

ZIA: Detroit is a — was a one-industry town. It was all about cars. Just to give some context, back in the 1980s, minimum wage was about $1.50 an

hour. That’s what I would’ve gotten as a college graduate. When I got a job at a stamping plant, a unionized UAW stamping plant, I got almost $10 an

hour and every benefit you could imagine.

And so, it was an industry where people wanted those jobs. These were secure, high-paid jobs that could get you, not only your own home, but a

summer home, a car, another car, an RV. And what happened in the 19 — late 1970s, after an oil crisis and gas prices, that we’re facing today, the

auto industry collapsed. People couldn’t afford to buy American cars anymore. They got seven or eight to nine miles a gallon. Gas prices went

from 40 cents a gallon to $4 a gallon, that would be as so today. Gas went to $6 a gallon.

And so, people lost their jobs. They lost these incredibly secure — once secure jobs. People who had worked for 30 years, and what happened was an

entire region, not just the City of Detroit, but everything connected to manufacturing collapsed. And that was the industrial Midwest. People were

out of work and it looked like they’d be out of work for an indefinite period of time.

And what that meant was in a time of intense suffering of the American people, folks were susceptible to the idea of blaming somebody. Who is

causing my misery? Who is taking food from the table of my children and the future of my grandchildren? And so, that was the time.

And initially, the automakers blamed the workers. The unions blamed the auto companies. People blamed the government for taking away benefits. And

somehow, there was an alchemy that came together to say, let’s blame Japan. Japan is the cause of the collapse of the auto industry because they

produced fuel-efficient cars. You know, Germany, actually pioneered fuel- efficient cars. And many people were buying German cars but it wasn’t declaring Germany, and people who look German to be the enemy of America.

Instead, it was Japan and anyone who looked Japanese. And unfortunately for Vincent Chin, that’s what he encountered that night when he was celebrating

his bachelor party.

SREENIVASAN: So now, let’s fast forward 40 years. We also have climbing gas prices. We have inflation on the rise. And oh, by the way, we’ve also had a

pandemic for the past two years that has — that started in China, whether that was intentional or not is controversial to some people. But

ultimately, we see a similar scapegoating.

ZIA: Asians in America have been scapegoated from the very beginning of when people of Asian ancestry set foot on this continent. And it’s

something that we can trace from the early 1800s throughout the 1800s, 1900s, World War II, the war in Vietnam, the 1980s when Vincent Chin was

killed. There is a master narrative in America that says, who is really American?

And for people whose ancestry is from Asia, the idea is that we are the perpetual foreign invader who our intent to come to America to steal jobs,

to set up shop in a neighborhood and steal the neighborhoods’ money, to take intellectual property, to destroy America. And that’s been a theme,

whether it’s in the movies, whether it’s in the halls of Congress, or in video games. And so, unfortunately, it has been a threat.

And so, here we are at another time when, yes, it’s a time of rising gas prices, two and a half years into a pandemic, everybody knows somebody

who’s been harmed or hurt from this pandemic. Yes, there is been very bigoted finger-pointing blaming China.

And because of that, everybody who — not only looks Chinese, but even just reminds people of Asia. I mean, there are so many people who have been

attacked who are not East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, Latinx people, who happen to remind people of — that they might be Asian have

been attacked. The thing about it is that hate violence doesn’t restrict itself to one group.

Yes, Asian-Americans are being targeted. This pandemic has really triggered a terrible time for Asian-Americans. But we also see a rise in hate

violence toward pretty much every group. You know, whether it’s antisemitism or transphobia, or, you know, what we’ve seen and Buffalo or

El Paso. And hate is a toxin. And so, this is a — this is an issue for all society, it’s not just an Asian-American problem. This is an American

issue.

SREENIVASAN: I’ve got to wonder, I don’t know if it’s even a fair question. But are things better or worse than the climate that you found yourself in

40 years ago arguing on the — on behalf of the rights of Vincent Chin? I mean, did you imagine that 40 years later you and I might be having a

conversation with such a similar atmosphere?

ZIA: 40 years ago, we would have had no idea that we’d be reliving something. A cycle that is, unfortunately, renewing itself. There is a

difference though. And that is that back in the 1980s, there were far fewer Asian-Americans. There’s more than 24 million Asian-Americans. There are

larger numbers in the halls of Congress who are speaking up for our communities. And as well as reaching out to other communities.

And so, there is a light, I guess, we can say. In terms of the hate that we’re experiencing, I think there’s a general consensus that this is worse

than the 1980s. You know, on top of an economic crisis that we’re only at the beginning of. We don’t know when this is going to end. We don’t know

when the pandemic, that’s on top of it, that’s global, is going to be, you know, something that we can look in the rearview mirror. We just don’t know

that.

And so, you know, with the mass killings that we’ve been seeing with the constant hate every day. Something in the headlines people don’t know

whether they can send their children off to school or even go to work themselves. And so, there is a feeling that this is worse. And the, you

know, the idea that back in 1982, Vincent Chin could be killed as though he were an animal, being beaten to death with a baseball bat. While in New

York City, we see an elderly woman who was being stomped on more than 100 times on her head as though she is an insect.

And so, there is a clear dehumanization process going on. And with U.S.- China relations not really showing any sign of improving in the near term, you know, the view that China is the existential threat to America. We hear

that all the time, too. That does not bode well for Asians in America.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that I remember from the film, just also — just reading about Vincent Chin is that, if there was a silver lining is

that it did galvanize a movement into being. That it did unify, in many ways, so many different types of Asian-Americans but also other people, as

you mentioned. And I wonder, are there events now that have the same impact?

I mean, last year, when the attacks happened on the spot in Atlanta, Georgia, it seemed like an unthinkable crime. But at the very beginning,

and sort of one of the first press conferences, you know, you remember the police officers say, I don’t think race was an issue. I mean, it was so

quickly dismissed until the, sort of, the people dug in deeper. But you see that response so often that I wonder if there is that galvanizing effect

for people saying, hey, this is actually happening today and racism is a factor here.

ZIA: Well, there is a galvanizing effect. I think that it will take time. One of the things that’s happened also in these 40 years has been the

really pervasive efforts to drive wedges, to separate people, to say one group is better than another, one group is worse than another. And for

Asian-Americans, that’s been this view that Asian-Americans do not experience racism. That there is no discrimination against Asians because

of — we are virtually white. We are the — this racist view of being a, “Model Minority”.

And that is a — meaning, we are the good minority which pits us against people who are presumed to be the bad minority.

And that’s been incredibly corrosive, divisive thing that was not invented by Asian-Americans, by the way. It has a time and a place, 1966 was when

this first emerged by a white sociologist as a theory. And that has become so ingrained that that police officer in Atlanta, the very first thing he

said was, oh, it has nothing to do with race. Asians don’t experience racism.

This has been said over and over and over again in other mass killings, of the first schoolyard shooting that was in 1989. A school in Stockton,

California of mostly Southeast Asian refugee children. You know, fiver, eight-year-olds were shot to death then. And the first thing the police

officer said, the chief was — this has nothing to do with race. Well, there was an outcry that then led to an investigation, finding that the

killer actually had white supremacist ties. But that is, kind of, the knee- jerk reaction when something happens to Asian-American.

Even with this pandemic. When there were, you know, videos that went viral, people said, oh, I didn’t know Asian-Americans could experience

discrimination. Well, in fact, that’s a sign of the ignorance that we have. The things that are missing in history. Which is why it’s so important that

Illinois and New Jersey legislatures have mandated that some kind of Asian- American curriculum should be taught K through 12. Because this lack of understanding is really a problem. And unfortunately, we have more than

11,000 accounts, you know, in the last two and a half years to show that, actually, it is a problem.

SREENIVASAN: I ask, in part, because when you survey Americans, about a third of them don’t feel like there are any increased acts of racism or

violence towards Asian-Americans. And I also wonder how much of that is our own communities, at least first-generation immigrants are taught to just

focus on your education. Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get political, right? I mean, because I’m trying to figure out, how is this reality so separate

from the perception of the reality?

ZIA: You know, for immigrants, and I’m the daughter of immigrants, too. My parents didn’t know anything about what it meant to be Asian in America, or

Chinese in America. They were too busy trying to just survive and adapt to an entirely different culture. And also, they felt like they were guests in

America. So, they were not inclined to try to figure out how their children might be more integrated in American society as American voices in a

democracy.

And so, the idea that if you keep your head down, you know, you’ll encounter less problems. That was something we faced as an issue that

people raised during the organizing around Vincent Chin. People said, if we speak up, will we risk more trouble? And we had to say, if we don’t speak

up, these things will happen all the time. And so, that is really, you know, a mind shift that it takes for an immigrant group. And that, I think,

is the time we are in now.

If we just hide out, things will, you know, clear up eventually. That is also being part of the problem. Because we’re seeing that it doesn’t matter

whether you’re an investment banker on your way to work in New York, you could be pushing in front of a subway train. And I think that is waking up

a lot of people, too. And I think for other Americans it’s seeing, well, OK. Today is an AK-47 aimed at Asian-Americans but that can be turned

against anybody, in any schoolyard.

And so, I think there is a broader recognition that there’s something deeper here. And for Asian-Americans, that’s certainly something that we

need to actually think about, talk about, talk about with our children, and our elders. Why is this happening? And to really see that in a democracy,

it’s true, those who speak up more get hurt. And if you’re silent, and you don’t speak up, you know, you — you’re under the bus.

SREENIVASAN: Helen Zia, thanks so much.

ZIA: Well, thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: To mark the anniversary, PBS is rebroadcasting the documentary, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” And it’s streaming now on pbs.org through July

of next year.

That’s it for now. I’ll be taking a load of accumulated vacation time until the end of August. My colleagues, Bianna Golodryga and Sara Sidner will

take you brilliantly through the summer here on “Amanpour”.

And you can always catch us online and on our podcast. Thank you for watching and goodbye from London.