Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

KYAW MOE TUN, MYANMAR AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS: We need for the strongest possible action from the international community.

AMANPOUR (voice-over): Myanmar’s U.N. ambassador speaks out against his own military leadership as the violent coup leaves at least 80 dead. He

joins me today, along with Britain’s ambassador to the U.N.

And:

OLIVIA COLMAN, ACTRESS: There’s never been any question to be living in Paris.

ANTHONY HOPKINS, ACTOR: Yes, there was. You told me.

COLMAN: No, I didn’t.

HOPKINS: I’m sorry, Anne, you told me the other day. Have you forgotten? She’s forgotten.

AMANPOUR: “The Father,” a groundbreaking film, has us experience dementia from the inside. I speak with the writer and director Florian Zeller.

Then:

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: I’m just one who has woken up, when the rest of you are still sleeping

AMANPOUR: “The White Tiger” digs into India’s pernicious caste system. Our Hari Sreenivasan talks to producer Mukul Deora.

And finally:

GEORGE W. BUSH, FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: The science is clear. These vaccines will protect you and those you love from this

dangerous and deadly disease.

AMANPOUR: A rare moment of bipartisan consensus in Washington.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The United Nations is ringing the alarm bells today. The U.N. special rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar says the junta’s brutal crackdown on

peaceful protesters are likely crimes against humanity.

Now, you may remember this compelling emotional appeal from the country’s own ambassador. He was speaking out against the violent military coup,

asking the international community to use any means necessary to provide security for his people.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TUN: We need for the strongest possible action from the international community to immediately end the military coup, to stop oppressing the

innocent people, to return the state power to the people, and to restore the democracy.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: At least 80 civilians have died since the junta overthrew the democratic government on February 1.

The United Nations Security Council has now just unanimously condemned the ongoing violence there and it’s calling for the release of the elected

civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi.

But there was no reference to the word coup in the statement, nor any call for specific further action. For its part, the junta says it respects the

international community, but it is nonetheless forging ahead with its own plans. Eleven people were killed in protests on Wednesday alone.

In a moment, I will talk with the British ambassador to the U.N.

But, first, Kyaw Moe Tun, who issued that plea to the world that went viral last week, joins me from New York.

Ambassador, welcome to the program.

Can I just first ask you what gave you the courage to take on your own military regime and stand in front of the world and condemn them in public

at the United Nations? What was going through your head at that time?

TUN: Oh, thank you. Thank you so much for inviting me to this program.

And this, of course, the 1st of February is the day that many of us, including me, we feel like we lost our future. So, then following days, it

made things getting worse. So, we feel like waste our future. We don’t want to go back to the system that we used to be in before.

So, that thing give me a lot of courage to do the things that I — on 26th of February, that — on the day that I deliver the statement.

AMANPOUR: Yes, well, it was certainly courageous.

So, now, partly because of your courage, partly because of what’s happening on the ground and civilians being killed, we have seen that the U.N.

Security Council has had the meeting. It’s made the statement. We have also seen the reaction from the junta in Myanmar, saying, OK, you international

community, thanks a lot, but we’re just carrying on with what our plan is.

They say their plan is to hold free and fair elections. What do you think is actually the plan? What will happen?

TUN: Thank you so much.

First of all, I would like to thank the members of the Security Council.

Yesterday, the presidential statement issued by the Security Council is behind the consensus one. And so it’s every member state had a veto. But

that is why I would like to thank the — all member state, especially the (INAUDIBLE) and the ambassador Barbara of the United Kingdom for her

efforts to bring up the strongest possible messages from the Security Council.

The thing that I like to say thanks is that we have the unified voice from the Security Council. Of course, that did not meet our expectation. When I

mean ours, I mean the people’s expect — the peoples — expectation from the peoples of Myanmar, because, as you know, as you just mentioned, more

than 88 people die, killed, murdered.

So, we all feel helpless. So, we keep telling the international community that we need protection, so that — because, at that point, the statement

issued, even though it’s thanking all the member states of the Security Council, we’d like to have a stronger than what we have now.

So, with regard to the write plans…

(CROSSTALK)

TUN: Yes, sorry.

(CROSSTALK)

TUN: With regard to the plan, I don’t think we need to have the reelection, because the election that we have on the 8th of November is

very clear it is a free and fair election.

And it is — the NLD have the landslide victory. So, right after the election, and right after the announcement of the result, many leaders of

the world extended their congratulatory message to Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD.

So, to me, there’s no need to have the reelection.

AMANPOUR: Right.

So, let me ask you this. You have just thanked the world community for standing with one voice and condemning the junta. They did not use the word

coup in their statement. And, also, we know that there was no specific plan or response outlined by the Security Council meeting overnight.

And now Amnesty International is saying that the junta is using battlefield weapons on the streets in Myanmar against civilians, against peaceful

protesters. What is it that you think the world can do to try to stop this? Or is there nothing?

TUN: Thank you so much.

So, that is why I keep saying that we need — really need the protection. This — now what we are facing injustice, and the group of — a group of

people with guns and ammunition, but the people, innocent people with no guns and no arms.

So, this kind of situation that we are facing, so I don’t need to spell out how brutality that security forces are conducting in Myanmar. So, a lot of

people were killed. A lot of people were beaten. So, it is sometimes, when we see these kind of things on the social media and the TV screens, we are

speechless. We are very shocked.

So, we really need the help from the international community. We — you may recall that in my statement in the General Assembly on the 26th of

February, I specifically appealed the international — member states of the United Nations and the U.N. to condemn the military coup, to ask the

military to release unconditionally and immediately the — our leaders, Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint and lawful detainees.

And then we ask them in the international community to not to recognize the military regime and to restore the democracy and return the state power to

the people of Myanmar, and to support the CRPH.

That is, I specifically appealed to member states of the United Nations during my statement. But now things are moving in the wrong direction. The

situation is getting worse.

So, we all are people, innocent people, innocent civilian. We feel really helpless, so that we really need the help. We really need the protection

for the innocent civilian, so that is what we are looking forward to have the help from the international community.

AMANPOUR: I will ask the ambassador in a moment about what more can be done, but can I ask you something because it has confused the world quite a

lot?

You know, you also did support a resolution that was basically — you remember, last November, when the U.N. actually sided — put out a

resolution condemning your government and the military’s attacks on the Rohingya minority in Rakhine State.

And at the time, you called that U.N. statement discriminatory, and you yourself said: “The resolution is politically motivated. It is selectively

targeted on a specific country and narrowly focused on a particular community’s human rights for their political agenda, ignoring the

complexities surrounding the issue and challenges facing Myanmar during its complex and difficult democratic transition.”

You also refuse to accept in public that the military was attacking the Rohingya, and you were blaming it on the Rohingya rebels. And, as you know,

that has caused Aung San Suu Kyi’s to become very unpopular in the democratic world. They’re very disappointed in her allowing this to happen.

Can you explain to me whether you really believe that about the Rohingya or were you forced by the military and was she forced by the military to take

that public position? Can you tell me now what the truth is?

TUN: Yes, thank you. Thank you so much, because those happen in your Rakhine State.

At the time, what we see, things are exaggerated and so on and so forth. And then also, we always stress that, one, we are dealing with the issue in

the Rakhine State. The government, even when I talk to our colleagues here in Geneva, government is working on the thin line.

One is international community and one is that the domestic elements, so that we handle the issue very — the issue is very sensitive, very

delicate, so that the government is handling the issue in a delicate manner.

So, we — that is why what we are trying to solve the problem in an amicable manner. So, now, what happened, you see the Aung San Suu Kyi-led

government trying to solve the problem, but there are other things that those who doesn’t like to solve the problem successfully would give a lot

of pressure on the government.

Now it’s end to this 1st of February. So, I understand that the special envoy of the secretary-general on Myanmar, Ms. Christine Burgener, also

keeps telling them the coup can take place at any time.

So, that’s a situation that the government is in.

AMANPOUR: OK.

TUN: So, that is what we really need, the understanding from the international community.

Even I myself also mentioned about this point.

AMANPOUR: Right.

TUN: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Ambassador Kyaw Moe Tun, thank you so much indeed for joining us.

Now, Barbara Woodward is Britain’s ambassador to the United Nations. And she used her considerable diplomatic skills to bring Russia, China, India

and Vietnam on board for that unanimous approval of yesterday’s statement. So, what now? What more can the international community to do to stop the

violence and restore democracy in Myanmar?

Ambassador, welcome to the program.

You heard a little bit, obviously, about what the Myanmar ambassador was saying there, thanking you for your unanimous statement, but, nonetheless,

between the lines seeing that it was potentially a watered-down statement. You didn’t use the word coup. There was no prescriptive measures that you

decided or discussed about trying to help them restore democracy.

What do you say to that? And what more can the United Nations do?

BARBARA WOODWARD, BRITISH AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS: Well, good afternoon, Christiane.

And, first, I should salute the courage of Ambassador Tun and his eloquence. As he said, this is — we’re talking about losing our future, as

he said so eloquently. And we have seen so many young people on the streets of Myanmar, Ma Kyal Sin killed wearing a T-shirt saying, “Everything will

be OK.”

The images are truly harrowing. And I think that was partly what helped us bring the Security Council together.

Now, in our statement yesterday, we unequivocally condemned the violence and we called very clearly on the military to exercise restraint. And we

were clear that we would continue to monitor the situation, which is the basis for further action.

It’s true that we didn’t use the word coup. But the U.K., of course, has been very clear that we condemn the coup as the U.K., and we have taken

sanctions against 25 of the military leaders. We have now got a trade review under way preventing trade, which would fund some of the military,

as well as making sure none of our aid goes to the military, while helping on a humanitarian level.

So for the U.N., we still have a range of tools. But we are trying to send a clear message to the — for to the junta that — but also to open up the

space for mediation. And it was quite interesting, I thought, that the Chinese tweeted yesterday, after we published the statement, that it was a

time for de-escalation, diplomacy, and dialogue.

So, we’re trying to end the violence in order to create space to work our way towards a solution and back to peace.

AMANPOUR: OK. So how do you think a solution would look like?

Because as I said to Ambassador Tun, the junta said, thanks, but no thanks. You, the international community, we respect you a lot, but we’re going to

go ahead with our own current plans, which includes the violent crackdown on protesters. And what they say they want to do is create another

election.

Well, you heard what the Myanmar ambassador said to, that they don’t need to have another election.

So, I guess what I’m saying is, where’s the space for diplomacy? If China are the ones who have the most inroads — and I don’t know whether they do

— what can they say to the junta, who says no, sorry, we’re not interested?

WOODWARD: So, I think there are two particular avenues for diplomacy here.

One, as you heard from Ambassador Tun, which is the U.N. special envoy, Christine Burgener, who I know that you have spoken to earlier on last

month. And she is in constant contact with the various parties here. And we are strongly encouraging them the military to allow her to visit Myanmar in

order to explore not just in Myanmar, but among the Southeast Asian partners, what can be done and where the avenues are.

And the second avenue, of course, is ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. We have been in close touch with them. They met, indeed, and

issued a statement where they underlined the importance of the principles of democracy, good governance, and that this was a regional problem.

So they are looking to find their way forwards to try and stabilize the region and help the people of Myanmar.

AMANPOUR: Ambassador, let’s just pick that apart a little bit, or, rather, get you to explain it a little bit. I assume Singapore is part of ASEAN. Of

course, the United States is part of ASEAN.

Singapore is one of the biggest business, I guess — people who have the biggest business amongst those countries with Myanmar. So are you calling

or should they be encouraged, as activists say, to stop that with the junta? Activists are also saying that the U.S., the E.U., U.K. should put a

ban on any arm sales to the junta.

Is that under consideration? Is that being done?

WOODWARD: So, there’s quite a lot of elements there, Christiane.

So, first, on the arms embargo, the U.K. was one of the main architects of the arms embargo in 2017, which the E.U. put on Myanmar following the

atrocities in Rakhine State, which you were discussing earlier with Ambassador Tun.

And following our departure from the E.U., we have taken that into our own domestic law. So there’s already an arms embargo in place. In terms of

ASEAN, it’s just the Southeast Asian nations. So the U.S. is not part of that group. But, indeed, there is quite a lot of trade, aid and dialogue

which flows between those countries.

They operate by consensus, which is very helpful, but sometimes can be a little slow, but we are encouraging the trust that they have in order to

try and de-escalate the situation.

And you’re right. The junta does have sources of money. It’s hard to work out exactly what, but the U.K., for example, has been very clear that we

are not going to do any trade with Myanmar, which involves the — any companies which might be owned by the junta. There’s also reports of junta

money in various bank accounts, and trying to track that down in order to cut off their supply of funding, so cutting off their funding, cutting off

their arms, and then the courage or the people in Myanmar.

We have seen, for example, defections from the police across the border into India. Or even just leaving the cities of Myanmar and the courage of

the young people there, I think, is an important reminder of the fact that the junta, although their rhetoric is strong, are not in an unassailable

position.

AMANPOUR: And just another question, I guess, about red lines.

You heard me talk about the U.N. special rapporteur saying that the junta’s actions against the peaceful civilians could amount to war crimes or crimes

against humanity. And Amnesty International has said they’re using battlefield weapons against the protesters on the streets, and basically

saying: “These are not actions of overwhelmed individual officers making poor decisions. These are unrepentant commanders already implicated in

crimes against humanity deploying their troops and murderous methods in the open.”

So I guess, what are your red lines and what needs to be told to them now, and who will take that message to them?

WOODWARD: So, I would say that the U.N. Security Council has been consistent both in our statement on the 4th of February and again in our

statement yesterday, on the 10th of March, that human rights must be protected.

And we are very disturbed by the allegations of torture, by the arbitrary detentions that we have seen, by the number of people who have been

detained and disappeared. And so all of that will need to be taken into account, people would need to be held accountable. But we can’t start that

process until we have de-escalated the current violence.

AMANPOUR: OK, final question.

And I guess the question is, and we kind of go round in circles, how do you de-escalate the violence? But, clearly, that’s something that you’re going

to be discussing and trying to figure that out.

WOODWARD: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: I want to ask you, because you used to be U.K. ambassador to China. And we have all seen the latest Chinese moves in Hong Kong that

seriously damaged the prospect of that being a democratic future.

Apparently, they have issued statements or mechanisms whereby they’re going to vet anybody who stands for election for their fealty and loyalty to the

Chinese Communist Party, and all sorts of things.

One of the British parliamentarians, M.P., says: “It achieves a chilling level of tyranny that requires an immediate response from the U.K.

government.”

What do you — what should you do? What should the U.K. government do about this?

WOODWARD: So, I agree with you.

The latest decisions in Beijing really have hollowed out the space for democratic debate in Hong Kong. And I think, beyond that, it undermines

confidence and trust in China’s ability to live up to its international commitments.

And it’s worth remembering that the one country/two systems goes back to the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, a treaty launched with the

United Nations which was to protect Hong Kong’s way of life for 50 years from 1997. And we have now — we’re now clearly in breach of that treaty.

And so the — I think the international attention is very important, drawing international attention to the situation. And worth remembering

that the U.K. has made a clear offer to the people of Hong Kong, to British nationals overseas to live and study and work in the U.K., giving them a

path to citizenship.

AMANPOUR: It is really interesting, because, of course, you need China as well to help you in Myanmar.

We will continue watching.

Ambassador Woodward, thank you for joining us from New York.

Turning now to a film. It is called “The Father,” and it is really a cinematic coup. it is starring Anthony Hopkins and Olivia Colman. And it’s

racking up nominations this award season, with six for the — for the BAFTAs that were announced just yesterday.

As adapted from the international hit play, the film pulls off the virtuoso challenge of bringing us inside the head of its aging protagonist, as

dementia strips away his ability to process the world around him. Here’s a clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COLMAN: Dad, I’d like you to meet Laura.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: How do you do, sir?

HOPKINS: I say you’re gorgeous.

(LAUGHTER)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: Thank you. I must say, he’s charming.

COLMAN: Yes. Not always.

Laura has come around to help you.

HOPKINS: I don’t need her or anyone else. I can manage very well on my own.

Who are you?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Anthony, it’s me, Paul.

HOPKINS: Who?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: I live here.

HOPKINS: What is this nonsense?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Florian Zeller adapted his own play for the screen. And this marks his debut as a movie director.

And he’s joining me now from Paris.

Florian Zeller, welcome to the program.

Obviously, the play and now the film is getting huge kudos. And it’s really interesting, first of all, to know that you actually — your own — I think

your grandmother was one of the inspirations for this story. Tell me about what made you want to do this.

FLORIAN ZELLER, WRITER/DIRECTOR: Yes, it’s true that “The Father,” before being a film, was a play. And when I wrote the play, I guess I was trying

to go through a personal experience, because I had been raised by my grandmother. She was like my mother. And she started to suffer from

dementia when I was 15.

So I knew a bit what it was to go through this painful process, and to find yourself in a position where you are important in a way. You love someone,

that you understand that love is not enough.

But it was not about trying to tell my own story, because I also knew that everyone is related to this kind of painful issue, meaning that everyone

has a grandmother, or everyone has a father, and everyone has a — or will have to deal with this dilemma, which is, what do you do with the people

you love when they are starting to lose their bearings?

So it was more to share those emotions with the audience. And that’s really the reason why I made the decision to make that film.

AMANPOUR: And, honestly, I think we have heard even more about dementia and the fragility of elderly people throughout the pandemic, because so

much of that is taking place in the care homes and so much death and illness has happened there, that it’s really entered the global

consciousness, maybe more than it might have done before.

Can I ask you, though, because — well, related to that, you kind of put the viewer into the head of the patient, Anthony, you have called him —

and we will get to the name in a moment. And the film, you really play with space and time and different characters to — I guess to confuse us as well

and to make reality very intangible for the viewer.

Talk to me a little bit about how you did that.

ZELLER: Yes, it’s true that the idea was to put the audience in a unique position, as if they were trying — as if they were going through that

labyrinth, because I wanted “The Father” to be not only a story, but also an experience, an experience of what it could mean to lose everything,

including your own bearings, as a viewer.

So, it was the narrative taken from the play. But what I didn’t want to do was just to film a play, and to find a visual way to play with the feeling

of disorientation, as if, in a way, the viewer were in Anthony’s mind, you know, and in order to experience what it could mean to doubt about what is

real and what is not real.

And, for example, I remember, when I wrote the script, I draw the layout of the apartment, and I really wanted to use the sets in order to play with

this feeling of disorientation. In a way, the set was to me like you’re a labyrinth . And I wanted to use what could be used thanks to the cinema to

make that experience very — like an immersive experience.

And, for example, at the beginning of the story, you are in Anthony’s apartment. There is no doubt about it. You recognize his space, his

knickknacks, his pieces of furniture, and step by step, the set is changing.

There are some metamorphosis on set, so that you recognize the space, you know where you are, but, at the same time, you are quite not sure. And you

have to go through this doubting process all the time throughout the whole film, because I didn’t want to tell that story from the outside.

There are many films about dementia, but it’s always told from the outside. We know where we are and you know where we are going. And I wanted that

experience to be more disturbing, more surprising, more challenging in a way, and to tell it from the inside.

AMANPOUR: Well, you use the word disorienting, and it really was disorientating. I mean, as a viewer, you achieve that.

I want to play one of the clips. It’s the doctor’s appointment clip and then we will talk about it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: Date of birth.

HOPKINS: Friday, 31st of December, 1937.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: Friday?

HOPKINS: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: You’re living with your daughter at the moment; is that right?

HOPKINS: Yes, until she goes to live in Paris.

COLMAN: No, dad, why do you keep going on about Paris?

HOPKINS: What?

COLMAN: I’m staying in London.

HOPKINS: You keep changing your mind. How do you expect people to keep up?

COLMAN: There’s never been any question to be living in Paris.

HOPKINS: Yes, there was. You told me.

COLMAN: No, I didn’t.

HOPKINS: I’m sorry, Anne, you told me the other day. Have you forgotten? She’s forgotten.

You’re starting to suffering from memory loss. I would have a word with the doctor, if I were you.

COLMAN: In any event, I’m not going to Paris.

HOPKINS: Well, that’s good. Paris, they don’t even speak English there.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Well, a little humor in there, a little anti-French sentiment.

I mean, he’s got all his faculties at work and then not a work and him slipping in and out of lucidity and not is also part of what makes it, you

know, really compelling. Tell me about — I guess what I — what kind of what struck me was that it seemed you were trying to say, or maybe I just

got that, that those who are around patients or family members who are sinking into dementia shouldn’t try to correct them all the time and try to

lead them back to their version of normality but maybe should just try to accept and roll with the punches. Is that kind of what you were trying to

say?

ZELLER: Yes. You are right. Because the world where we are in is so realistic but with no logic anymore. And so, it’s — it was a way to make

you experience that sometimes it looks like a nightmare and probably to be around who is someone suffering from dementia and to love him or her is not

about trying to reconnect him to what is real for you but just to be around and to give your time and your love in a way.

Because this is not only the story of this man losing his bearings, it’s also the story of his daughter trying to face this painful dilemma. And, I

mean, it must be such a difficult situation, you know, when you are becoming the parent of your own parent, you don’t know what to do and there

is no right answer. I mean, it’s not about telling what should be done or what the character should do, because there is no right answers. It’s just

about, you know, sharing that — those emotions.

And I think that even though, you know, it doesn’t change your real life, I think there is a consolation and the real one and a beautiful one in a way

just to remember thanks to film that we are on the same boat and that we are just part of something larger than ourselves, because we all have those

same fears and we are all connected, you know, this is humanity, painful humanity. But still, I think there is a consolation here.

And this is what I have experienced, thanks to the stage. Because I was not certain that the audience would be open to such a journey. And when the

play was on stage in France and then in other countries, I was really moved to discover the response of the audience, because it was always the same

everywhere in every country, meaning people were waiting for us not — after every performance not to say congratulations but just to tell their

own story, to share their own story.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ZELLER: And I realized there was something really cathartic about it and this is really why I wanted to make that film, just to make people remember

or feel that we are all, you know, connected.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I want to ask you specifically about Anthony Hopkins because your original character in the play, the protagonist is called

Andre, and you changed it to Anthony for the film and you wrote it for him.

ZELLER: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I want to play a bit of an interview that I did with him about another great character he played not so long ago, “King Lear”, also

wrapped up in mortality and trying to, you know, understand that. This is what he told me about this issue then and then I want to talk to you about

Hopkins, himself.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HOPKINS: Now, I understand the muscle of the man, the power of the man and about old age and about loneliness and about death and I’ve always had that

sense in my nature about death. And my favorite poems are about not death and mortality, but about the certainty of life, about the certainty of

mortality. And like Tia Selit (ph) I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker. And I have seen the eternal footman hold my coat and snicker and

in short, I was afraid. And that, to me, represents everything that is from my past, from my father, my grandfather, about death and about mortality.

That life is tough and you have to be tough to match it.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you know, he is talking about what he brought to the stage for “King Lear”. But all of these days on he is also bringing all of that

to this last chapter in his life in “The Father.” So, what was it about Anthony Hopkins that made you pursue him and him alone for this? And what

perspective did he bring to it?

ZELLER: To me, personally, I think he is the greatest living actor. It was the beginning of the desire. I am French, as you can hear. This is

something I cannot hide. So, it would be easier for me to make a French film. But as soon as I started dreaming about that film, because everything

starts with a dream, the one and only face that came to my mind was Anthony’s. And I had this conviction that he would be so powerful in this

part. And that is the reason why I wrote — I mean, the main character’s name is Anthony because I really wanted him to know it was written for him.

And I remember when we first met, he questioned me about this idea to keep Anthony as the character’s name. And to me, it was important because I

didn’t come to him to ask him to do what he is known for but to try to explore a new emotional territory and to go this very fragile and

vulnerable place. And in a way, I think that to keep that name, Anthony, helped us. Because it was not about, you know, creating a character. It was

not about trying to tell a story in a way to fake an old man with a disease. What we tried to do was — I mean, I asked him just to be in front

of the camera and to — no acting required in a way, and to use his own fears and to be connected with his own feeling of mortality.

And I think he was really brave to accept to do that because it was not easy and he put himself at risk in a very profound way in my opinion.

Because, you know, he accepted to — just to explore this part of himself during the shooting. And sometimes it was a painful process but he was so

generous and so humble also. And that’s why I am so grateful and so happy that I had this opportunity to do it with him.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And Olivia Colman, too, who gives the tour deforce as the daughter. It is really remarkable.

Florian Zeller, thank you so much. Again, you have BAFTA nominations, it’s awards season and it is an amazing film. Thank you so much.

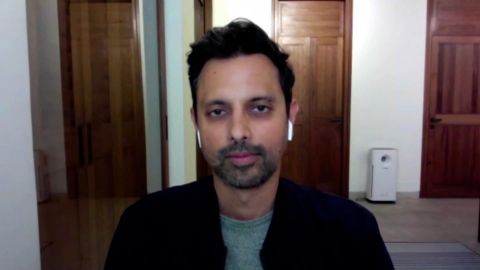

Turning now to another film critics are already calling a roaring success. It has also just been nominated for two BAFTAs. “The White Tiger” tells the

story of a Balram, a poor but shrewd young driver in India battling against the country’s culture of servitude and inequality, otherwise known as the

caste system. It is based on the 2008 Booker Prize-Winning novel by Aravind Adiga. And Mukul Deora is the producer. And here he is talking to our Hari

Sreenivasan about the Netflix movie which he spent a decade making.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Thanks, Christiane. Mukul Deora, thanks for joining us.

Your film has just been nominated for BAFTA awards. It’s doing great in several countries around the world. For those who haven’t seen the film,

here is a quick look at the trailer.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: When I first saw him. I knew then this was the master for me. I want to be a driver for your son.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Hey. (INAUDIBLE).

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Hey, don’t do that.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Hey. Driver.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Thank you. Nice to meet you.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Balram, have you ever seen a computer?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: We heard many of them in the village with the goats.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: The goats are very pretty advanced to use computer.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: OK. Now, you’re being a jerk.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I didn’t like the way he had spoken about me. Since I was a boy, the desire to be a servant had been hammered into my skull.

I, Barlam, I drove the car. I was alone in the car. They made me sign that confession.

SREENIVASAN: This is a haves and have not story. When you look at kind of — that narrative of having a struggle between someone’s coming up, that’s

as old as movie making, as old as storytelling, but what was so compelling to you about this particular type of story?

MUKUL DEORA PRODUCER, “THE WHITE TIGER”: You know, a bunch of things. Firstly, it was set in India, you know, that I knew but it was so fresh for

a book, a prize-winning book. It’s written so economically, so direct. And, you know, honestly, the genius of the author, Aravind Adiga’s writing is

that these concepts that he created, the half-baked man which is this person whose knowledge has come from here and there from limited bits, like

lizards falling from the ceiling into your head. Beautiful, you know?

The Rooster Coop, which is a central concept of this movie as well. You know, why are so many people all over the world trapped in servitude?

Because like rooster, they just can’t escape. I think that is a very important thing for me that when I read it, I felt I’m reading something

else, you know, I’m reading — this isn’t a normal, you know, book of fiction. It is just so deep. And, still, you know, so funny and so dark.

Really cuts to the bone basically, I think.

But to your point about, you know, what would someone in the world think? Yes. It is a story of haves and have nots. And I think everyone has to

break free, you know, whether it’s societal or familial or financial. You know, breaking free is really an evolution that you have to go through in

different ways. So, I think people could relate in that way as well.

SREENIVASAN: There is another clip I want to show. It’s kind of a little bit of the relationship between the driver and who he is driving. Let’s

take a look.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Do you know what the internet is?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: No, sir. But I could drive to the market right now, sir, and get as many as you want.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: No. It’s OK. Thank you. Do you have Facebook?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, sir, books. I read a lot of books, sir.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, I heard you can read. Have you ever seen a computer?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, sir. Actually, we had many in the village with the goats.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Goats?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, sir.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: The goats are pretty advanced to use computers?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I could tell from their faces I had made a mistake.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You see? He has two, three years schooling in him. He can read and write. But he doesn’t get what he’s read. He’s half-baked.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: OK. Now, you’re being a jerk. He is standing right there.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: No, I’m not. I’m not being a jerk.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Come on.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You’re missing the point here. Our driver represents the biggest untapped market in India waiting to serve the web by a cell

phone, rise up into middle class, something I can help him do. You are the new India, Balram.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I am the new India, sir.

SREENIVASAN: You know, there’s people that are going to watch this and say, well, this is almost a conversation between Netflix and India. You’re

the new market. You’re the place that we want to get. You are who we want to reach because we see massive growth potential there. I mean, and —

well, really, so does anybody selling any products on the market.

DEORA: Any product, any product, right. You know, it is interesting, because actually those three people, they are all three different Indias.

Pinky Madam is an Indian that we all know who is not really Indian. She spent most of her life abroad. She’s not really — doesn’t have any roots

in India. And she comes back and she is completely alien to the whole thing, you know, just looking around and like oh, my god, shocked or — but

she is the agent of change because she doesn’t have those shades on her.

Ashok is another India we know who is born and brought in India but has spent some time in the west. He’s got a mix accent. He is, you know, in the

middle. He’s like, you know, I’m a little bit this, I’m a little bit old school. I’m like my dad and I’m not. I’m trying to be friends with my

staff. And the Balram is the new India. You know, as you said, the India that the whole world is jumping in to be, you know, to sell things to

basically.

And the movie is like a family tree. It’s all showing different Indias, different parallel universes that exist in terms of how they view power,

how they view opportunity, you know, how they — you know, people born to servitude. The have and the — different levels of the haves and have nots

and exposure from different parts of education coming together. And like you — you know, that’s a very interesting because that shows in a little

snapshot of the whole thing, it shows what is globalization today, what is the valuation of all the big tech companies because they have to be in

India and slam it out and spend billions of dollars, because if they don’t, there’s no growth.

SREENIVASAN: Is there something in the air here? I mean, just a couple years ago we had the success of “Parasite” which kind of looked at

literally this underbelly that was happening that nobody really wanted to discuss, they just knew that it existed. And here you are talking about a

kid from a village who, you know, it locked into a class structure.

DEORA: I think what’s happened in the last many years is that, there’s two things. There’s globalization that’s happened, you know, in a massive way,

India is, you know, along with China are the fastest growing markets in the world. So, you have the powers that be — in the media and entertainment

business. You know, the Netflix, Amazon, the studios who are all now — you know, they have to be in India and they have to, you know, engage with that

whole thing. So, there’s that bit.

But in the same time, in America, as you know very well, there was an awakening, I guess, in the last few years of — you know, on the systemic

issues that were there and continue to be there since time memorial, I mean, in everything we do, but specifically in the media and entertainment

industry it became, you know, very clear and very strong, maybe exacerbated by what happened in the last four years in America, I think it definitely

made — you know, put a merit to people’s faces as well and forced everyone to have uncomfortable conversations and take sides.

And I think those two things together — these stories were always there, you know, whether you’re — like you said, a Korean domestic staff, an

Indian driver, a Mexican housekeeper in Roma, these stories were always there, they were always amazing stories, and I believe there is always an

audience for them but it just wasn’t clearer to the part that be (ph) that that — you know, how do they reach that audience, does that audience

exist, was it financially viable to make something, to reach that kind of audience. And now, those — let’s call them beautiful experiments, are

happening and gaining momentum everywhere and people want to hear honest stories and people feel, you know, connected to these kinds of things,

definitely. Yes.

SREENIVASAN: You know, I mean, I was born there. I’m still connected to the country. My relatives are there. Each time I go, sometimes I notice the

changes. But one of the things that your film points out is how much of India has changed, even beyond the Incredible India campaigns and the huge

leaps forward and sort of technological dominance that the country has had and there is this core of this story of Balram that regardless of what part

of the country you go to, you can still see.

DEORA: I mean, honestly, what has happened and what I think that pandemic has really exacerbated as is this battle to — you know, now, at least

people are aware of it that, what is it like, I don’t know, 80 percent of the world is controlled by one percent of the population. And yes, I read

somewhere that that 30 families control 50 percent of that world.

You know, some — you know, the numbers are just insane. So, honestly, I think that’s happened, you know, when I look at England, when I look at

America, when I look at India, when I Look at every country in the world has this massive inequality problem. Yes, and I think this movie just shows

that basically, you know, and what some — the cost of freedom. I mean, that’s — I think that’s — when people ask me what is this story about? I

say, for me, it’s different. A lot of people say ambition. But for me, it’s about freedom and the price that someone has to pay, and how high is that

price. We all have a price of freedom. But for Balram, it was a very, very high price to pay.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that the character brings out is how he normalizes sort of the situational ethics of this inequality. Let me play

another clip here.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Over the week’s, I learned the ways driver cheat their masters. Number one,

give your master phony invoices for repairs that are not necessary.

Two, sell your masters petrol to other drivers. As you gain confidence, cruise around picking up and dropping off paying customers. Delhi has many

pick up points. Overtime, you will learn them all.

When I looked at that cash, I didn’t feel guilt, I felt rage (ph).

SREENIVASAN: I want to ask a little bit about the star that we’re seeing here, other scar of his preparation for this was a bit intense.

DEORA: It was very intense. You know, it started with — when we — when Ramin, the director, and me saw him in the auditions. I remember we spoke

to each other and we said, this is the first person we’ve seen convincing a bunch of people. Let me see Balram. That’s Balram. We don’t see — there’s

no artifice. There’s nothing. It’s just him.

And he — I mean, you know, after, you know, we — you know, we agreed that he would do it and everything, he became a driver without the people

knowing it. He went to, you know, a village in that region and spending a lot of time there. I’ve been to a mall when we were prepping.

And I was getting on the car and I turned left and I saw him sitting and chilling with a bunch of drivers and he just looked at me dead and, you

know, then maybe there’s a twinkle, maybe there wasn’t and I didn’t see anything. And, you know, that was him just being in that zone. You know, he

got menial jobs as well. Like real menial jobs. You know, lifting things, carrying things. And he really read into it, yes. And it shows, you know,

it shows.

SREENIVASAN: It’s also because his acting skills, I mean, he makes Balram, well, likable at times. I mean, depending on whether you see him as the

hero or the villain or of some combination thereof, it’s a very fine sort of tightrope to walk and it was just intriguing to watch kind of his

innocence fade throughout the film.

DEORA: It was — it’s true and it was a very, you know, important thing for us to make him likable as well. You know, because the story is — it’s

an indictment of humanity on one hand but it is also a celebration of humanity. Because at the end of the movie he’s like, I’ve made it. You

know, yes. I’m done. So, it had to have, you know, that flow where you do – – I mean, look, killed someone. He killed someone who’s not necessarily the worst person at all in this — you know, a weak person but not worth, you

know, killing.

So, you had to make him likeable so you, you know, empathize with him through the whole journey and you really feel for him, you feel for his ups

and downs, highs and lows and all that. But, you know, that clip that you just showed me just reminded me of something. I was just going to share

with you which is that, you know, so many people have called me up and said this and that and everything, but older people in India, like friends’

parents or parents’ friends.

I met a friend of my mother and she sat down with me and she said, I want to tell you about the movie. And I said, sure, aunty. And she was like, I

couldn’t sleep for four nights after I watched the movie and I was thinking, should I — I’m a good person. I take care of my staff. I’m good

to them but we don’t do enough. We just don’t do enough. There’s so much more that we can. We really have to do more.

SREENIVASAN: You know, after having studied and read the book for so long, after having watched the process of making the movie. Why do you think

class or caste or your place in society still has the power that it does?

DEORA: Oh, that’s a good question. I think it was just human nature in some way to, you know, bill systems of — I guess it’s one part of human

nature to build systems of subjugation, you know. And because — I mean, when you look, what is the history of the world? The history of the world

is written in blood. It’s all subjugation, slavery, you know, horrible atrocities committed in the name of economic growth sometimes, not even

something, you know, like racism. It’s just like economic growth. And we have to grow and these are the brown skin or black skin or whatever

different people from us, we are going to, you know, be our workforces and help us grow to where we have to grow.

Same skin people. I mean, people had — you know, you had people doing the same thing to people of their own race. So, I think when you look at

history of the world, it is that. And I think — you know, I like that saying, all that a good man has to do to ensure the triumph of evil is

nothing. So, you — you know, and you saw what happened in America in the last — you know, this whole this whole amazing on circus that’s happened.

And there’s hope. You know, who knows.

SREENIVASAN: Mukul Deora, the film is called “White Tiger,” it’s on Netflix. Thanks so much.

DEORA: Thank you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And that was a very powerful saying there. And finally, today, marks one year since the W.H.O. officially declared corona virus a

pandemic. But 365 days on hope is inside in the form of multiple vaccines. In the United States, former presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George

W. Bush, Barack Obama and all the 1st ladies have been vaccinated on camera, trying to dispel any anxiety about it.

Here is their P.S.A.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BILL CLINTON, FORMER U.S. PRESIDENT: Right now, the COVID-19 vaccines are available to millions of Americans. And soon, they will be available to

everyone.

BARACK OBAMA, FORMER U.S. PRESIDENT: This vaccine means hope. It will protect you and those you love from this dangerous and deadly disease this.

CLINTON: I want to go back to work and I want to be able to move around.

OBAMA: With Michelle’s mom, to hug her and see her on her birthday.

GEORGE W. BUSH, FORMER U.S. PRESIDENT: You know what I’m really looking forward to is going opening day in Texas Ranger stadium with a full

stadium.

CLINTON: We’ve lost enough people and we’ve suffered enough damage.

BUSH: In order to get rid of this pandemic, it’s important for our fellow citizens to get vaccinated.

JIMMY CARTER, FORMER U.S. PRESIDENT: I’m getting vaccinated because we want this pandemic to end as soon as possible.

OBAMA: So, we urge you to get vaccinated when it’s available to you.

BUSH: So, roll up your sleeve and do your part.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: This is our shot.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Now, it’s up to you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And here’s what vaccinated actually looks like, families allowed to reunite and hug for the very first time since the pandemic began.

That’s it for now. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” and join us again tomorrow night.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END