Read Transcript EXPAND

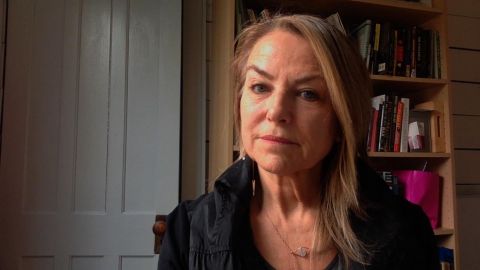

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Our next guest has been personally affected by the coronavirus. Peggy Flanagan is Minnesota’s lieutenant governor. And in March, her brother died because of COVID-19. Flanagan is the second Native American woman elected to statewide executive office in the United States. And she talks to our Michel Martin about how Native Americans, like the Hispanic and African-American communities, are being disproportionately hit right now.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Lieutenant Governor, thank you for talking with us today. We’re so delighted to have you with us.

LT. GOV. PEGGY FLANAGAN (D-MN): Thanks so much for having me. I appreciate it.

MARTIN: I do want to offer the condolences of everyone here on the loss of your brother. And this comes just after you lost your father earlier this year. So I do want to offer condolences.

FLANAGAN: Thank you. I appreciate that. This has certainly been a difficult year for our family. My brother — my dad was hospitalized towards the end of last year. My brother drove up north and stayed by his side until he walked on and until he was buried. And then he went home to Tennessee, and just a few weeks latter started feeling sick, and went to the doctor, and was diagnosed with cancer, received his first treatment, went home, and a few days later was admitted to the hospital due to difficulty breathing, a couple days later was tested. And it was confirmed that he had COVID. They needed to place him on a ventilator and put him in a medically induced coma. And he did not survive. And so my family, we will have the opportunity to memorialize him, and his ashes will be spread next to my dad on the White Earth Reservation. And we will have that opportunity in the future. But, right now, my brother is a Marine. And he would have said, girl, get back to it. And that’s what we’re doing. And so many other families are just trying to move through their grief right now.

MARTIN: I see. Well, again, condolences on that. And your story is that of so many others during this time. So, let us speak about your public responsibilities. You are the lieutenant governor of Minnesota. You are the second Native woman to be elected to a statewide office in the country. So, there are 11 Native tribes in Minnesota. But I understand that your concern about tribal members really speaks to tribal members across the country. Are there specific concerns about tribal members that perhaps are distinct from those of everyone dealing with the current situation that you want to highlight for us?

FLANAGAN: Sure. Well, I think, you know, one of the most important things for people to know I think is that we still exist. There is an erasure that happens of Native people. And IllumiNative is a nonprofit organization that conducted a study where they found that 40 percent of Americans don’t realize that Native American people still exist. So, if you don’t even know that we’re still here, addressing and helping to find solutions to the issues that challenge our community, that becomes even more difficult. But, additionally, our health disparities are something that our community certainly deals with, underlying conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and then puts us even more at risk for contracting COVID and then developing complications from that.

MARTIN: Among Native Americans, actually, the incident of these conditions is far higher than in the general population. Can you just share a little bit about that?

FLANAGAN: That’s correct. So, we are at the top of many of the lists that you don’t want to be at the top of. And so, again, when it comes to issues around heart disease and diabetes, any kind of complications, I think, you know, as we are tackling some of these things, too, we are also navigating through housing shortages and access to food, all the things I think that some folks take for granted and a lot of our tribal communities are not often easily accessible. And the biggest thing is that, you know, as we have been working with our tribes here in Minnesota, is just the acknowledgement that our tribes don’t have a tax base. And so much of the revenue source for our tribes has happened through gaming. And, you know, we certainly — the governor and I couldn’t issue an order asking casinos to close, but our tribal leaders made that decision on their own and followed the state’s stay-at-home order. And that puts them in a really difficult position. So, one of the things that we have also done is put together — as we were working on our response, in partnership with the tribes, we put together tribal assistance fund that we were able to move through the legislature. It’s $11 million in that fund to then give individual grants to tribal nations, so that they have some money while they’re waiting for the additional support to come in from the federal government, so that they can get reimbursed by FEMA and other things.

MARTIN: The reality of it is that millions of tribal members get their health care through the Indian Health Service, which was set up in exchange for access to, you know, tribal lands.

FLANAGAN: Right.

MARTIN: What is your understanding of the testing situation? We’re hearing from governors across the country that they’re competing with each other. Is the Indian Health Service similarly having to compete with other entities for these things? What is the situation there?

FLANAGAN: First of all, I’m glad that you acknowledge just the — we were guaranteed two things, which was education and health care, in exchange for all of this, the United States. Indian Health Service has never been adequately funded and has never met the health care needs of Native people. And so now we have this crisis on top of it. It’s simply only exacerbating, I think, some of those shortfalls. But when it comes to testing, that’s correct, that we — that the Indian Health Service is also competing with the states to get the testing equipment, the PPE. And we find ourselves in a situation where it sure would be helpful if the federal government did a better job coordinating throughout the states and with Indian Health. One of the challenges that we have had in Minnesota is, even when we receive these test kits as a state, the reagent that is needed for these kits or additional swabs are not included. And so if you’re sending out a kit, you can’t actually use it unless it’s complete. So we’re following up with the tribes in our state to find out if they have, in fact, received a full kit, so that they can begin testing. The need has not been met when it comes to testing, I think, for states, but especially for our Native nations across the country.

MARTIN: The federal government has pledged — as part of the latest relief act, has pledged some millions of dollars to the tribal nations for the same reason that this money is being sent to other groups and individuals. Has any of that money been received yet, to your knowledge?

FLANAGAN: Some of it has. I think the large amount of the $8 billion that was allocated by Congress, that money has not been distributed yet. And the issue there is that Treasury has never directly granted or sent money to tribes before. And so they’re trying to determine what the appropriate formula is for the disbursing of those funds. I’m worried about how that formula will be developed. There are 573 Native nations within the borders of the United States of America. And for an entity that’s not done this yet, I think, you know, we are all paying close attention to how they determine, as they’re going through consultation, how these funds will be disbursed. But we are weeks and weeks into this crisis, and I worry about the ability to get that money out quickly and for folks to — for tribal leaders to be able to meet that need. So I know that many folks are paying close attention.

MARTIN: Now, you were telling that there are 11 tribal nations in Minnesota, that you and the governor were able to put together a package for the tribal nations within the state, though. What’s their situation, though? I mean, is your worst-case scenario coming true there?

FLANAGAN: So far, we are — you know, we do daily calls with tribal leaders, along with our congressional partners. And, you know, I think that that’s been really important to make sure that we are communicating effectively with what the needs are, how to better coordinate with local county health officials, that type of thing. And we’re really — we were able to implement that because the governor and I have made sure that our relationships with tribal nations have been — has been a real priority for our administration. So, because of that relationship-building, we have been able to get to a better spot, I think, with coordination and response. Now, we do know that, at the Red Lake Nation, for example, 600 of their tribal members are experiencing homelessness. And even — and that is a real issue, as we’re thinking about how people can do social distancing, stay at home, limit exposure. And so we’re working with Red Lake on that particular issue. But our 11 Native nations — there’s four Dakota and seven Ojibwe nations in Minnesota. All have their unique situations. And we’re just trying to communicate and get them the resources that they need in the short term or at least make those connections that to be able to respond to take care of their communities. But the one other thing that I would mention here, too, is that 50 percent of Native Americans don’t live on reservations. And so we have a pretty significant urban population as well. And in Minnesota, you are 27 times more likely to be unsheltered if you are — than the white population if you’re Native. And so that is also an issue that we are dealing with here for our community members experiencing homelessness, which was already an issue, on top of making sure that we have culturally appropriate responses through cities and county and through the state. So, that’s something that we are working on now as well.

MARTIN: You’re saying a culturally appropriate response. Tell me more what that looks like and how that might be different than for other groups.

FLANAGAN: So, for folks in Minnesota, the populations that we see experiencing homelessness at a disproportionate rate is the Native community and the African-American community. So, having culturally relevant support means that, oftentimes, folks in our community prefer to be in shelter together. But we’re also working to support our shelter providers, as well as our street outreach folks. And even just today, I got a text message from the pastor at All Nations Indian Church in South Minneapolis, who said that they are setting up handwashing stations and a hygiene area, as well as connecting folks with food and medical care that’s available, that will be available three times a week. And so I think those are the kind of things where we need people to be creative right now and to meet folks where they are. The other ability, the other hygiene stations or port-a-potties or handwashing stations were throughout our — the city of Minneapolis in a place where they weren’t necessarily accessible to folks. And now it’s been an area where people will be able to utilize them, connect with each other, and our hope is also get the support and medical care that they need that is delivered in an environment where people feel comfortable and is part of the neighborhood.

MARTIN: Thirteen percent of Native American homes lack access to clean water, where the national average is less than 1 percent. That’s as a national statistic. You know, it’s been reported that and it’s been well-documented to this point that the death rate for African-Americans and Latinos has been demonstrably higher than for other segments of the populations. We’ve seen this in New York. We’ve seen this in Detroit. We’ve seen this in New Orleans. We’ve also seeing this in Washington, D.C. Is the same thing true so far of Native Americans?

FLANAGAN: I think that you can see it happening in Arizona and in New Mexico. And we are doing everything that we can here in the state, but I suspect that you can anticipate that the Native community will be disproportionately impacted by this as well here in our state, which is, again, why we need those resources. We need the additional health care capacity to be able to meet the need. But let’s just be clear. I think — you know, I have heard some folks — and I’m sure you have, too — say that, somehow, the coronavirus or COVID-19 is the great equalizer. And I think nothing could be further from the truth. What this has done is simply laid bare the racial inequities, the socioeconomic inequities that we have in our country, and knowing that, if you are a person of color, if you’re indigenous, if you’re an immigrant or refugee, that this virus will impact you in a way that’s (AUDIO GAP) substantial.

MARTIN: A number of groups, activists and political leaders like yourself have been raising your voices in recent days to call attention to these disparities. But I want to ask you about the other side of it. Is there any part of you that is concerned that, when this — it becomes understood that the impacts of this fall more heavily on some communities than others, particularly communities of color, that there will be less national urgency about it?

FLANAGAN: Well, yes, I certainly am concerned about that. And I think this country has a long history of not feeling the urgency when it is black and brown people who are most impacted. And so, you know, all I can do is work alongside the governor, but with other leaders. I think a lot about Lieutenant Governor Garlin Gilchrist in Michigan or Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes in Wisconsin. We are all deeply connected and lifting up these issues. And that is all we can do, is continue to really make sure that our people are seen and heard and valued.

MARTIN: Is there anything in particular that you are drawing inspiration from at this time to kind of guide you through this really unprecedented moment, at least unprecedented in modern times?

FLANAGAN: While Native people, you know, are at the top of every list as far as health disparities go and rates of poverty and other things, I also find great comfort in the fact that we are resilient. And despite everything, everything that has been thrown our way, we are still here, and that I have a 7-year-old, little Anishinaabekwe, little Native daughter, who knows who she is and knows where she comes from. And that is what — sharing our ways with her and knowing that we are still here, that brings me strength every single day.

MARTIN: Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, thank you so much for talking with us.

FLANAGAN: Thank you so much for having me. I appreciate it. Meegwetch.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane speaks with the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Kristalina Georgieva; psychotherapist Esther Perel; and composer Andrew Lloyd Webber. Michel Martin speaks with Minnesota Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan.

LEARN MORE