Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, with coronavirus spiking around the world amid easing lockdowns, all the more need for that coronavirus vaccine. In the global scientific rush, Russia is the latest, saying its vaccine will soon be approved, although no testing data has been released amid concerns about cutting corners. Right now, there are more than 165 vaccines in development, and 27 are in human trials. Carl Zimmer is an award-winning science writer with a weekly column in “The New York Times.” Here he is breaking down the biology with our Walter Isaacson.

WALTER ISAACSON: Thanks, Christiane. And, Carl Zimmer, welcome to the show.

CARL ZIMMER, COLUMNIST, “THE NEW YORK TIMES”: Thanks for having me.

ISAACSON: It’s been an amazing past seven days or so for vaccine, which is what we hope will all save us soon. And with your vaccine tracker in “The New York Times,” you have done a wonderful job tracking them. Why don’t we start with the one that I think may be furthest along, which is the Oxford vaccine? Explain to us where that is in phase three trials, and how that actually works. It’s a traditional vaccine.

ZIMMER: So, Oxford University has a vaccine which they are testing out with AstraZeneca, the drugmaker. And, basically, what it is, is, it’s a virus that delivers a gene into your cells. So, this particular kind of virus only affects chimpanzees. And so the thinking is that people have not been exposed to this before, so it will be effective for getting into cells. It can’t replicate, though. These kinds of viral vectors are actually engineered so all they do is just deliver a gene into your cells.

ISAACSON: So, when it delivers a gene into the cell, what does the gene do?

ZIMMER: Well, your cell looks at that gene like any other gene and makes a protein. And this protein happens to be one of the proteins made by the coronavirus. And so when your immune system sees it, the hope is it makes lots of antibodies that can then go after the real coronavirus, if you should get sick.

ISAACSON: Most of the proteins being made by any of these vaccines try to mimic the spike protein, right, on the surface of the coronavirus. Why is that?

ZIMMER: So, the coronavirus has this sort of halo of proteins, and these are called spike, as you say. And they use this protein to latch on to cells that in our nose or airway and then invade the cell. So, this seems to be the best target for our immune system. So, people who get sick with the coronavirus and then get better, the reason for that is their immune system figures out basically how to go after that spike protein, so the virus just can’t get into cells in the first place.

ISAACSON: So this Oxford vaccine is in phase three trials. Tell me where it stands, and when we might get results.

ZIMMER: So, this has been going in phase three trials for a couple weeks now, a few weeks now, in several countries such as Brazil. And it — we will have to wait and see. In a couple of months maybe, we might start hearing about results. It really depends on how many people are being exposed to the virus in these different countries. They really don’t have that much control over how long it takes before they start to see good results.

ISAACSON: So, maybe September, maybe October, we will start getting the first set of results?

ZIMMER: It’s conceivable, and I say conceivable, that AstraZeneca might be making emergency authorized supplies of the vaccine in October. That’s conceivable.

ISAACSON: Wow.

ZIMMER: Could be longer.

ISAACSON: Now, the other two vaccines that in the past week went into phase three trials are one by Moderna, and the other, I think Pfizer is taking the lead on it, maybe with BioNTech. And they do something different. They take a piece of messenger RNA and inject it into your cells. Explain to me why that’s different and why it might be better.

ZIMMER: So, the idea there is that — just to remind everybody of their high school biology, in order to turn a gene into a protein, first, you — your cell copies your gene into a piece of what’s called messenger RNA. And that then is used by your cells to make protein. So these researchers at Moderna, at Pfizer have been trying out just making a piece of messenger RNA, and then getting that into your cells, and then your cells just, boom, make protein out of it. And so there could be potentially some advantages. For one thing, it’s a lot easier to make a piece of messenger RNA or also a piece of DNA than it is to take some chimpanzee virus or some other more traditional kind of vaccine, because you’re just like dealing with a code. As soon as the genome of the coronavirus was put online, you could just say like, OK, there’s the gene for the spike protein, let’s just copy out the gene or messenger RNA version of it, and let’s get to work. So, that’s why Moderna was the first vaccine to go to human testing. It’s fast.

ISAACSON: And when do you think they will be getting results?

ZIMMER: Well, Moderna and Pfizer, as you mentioned, just started their phase three trials. So, that could be maybe a couple of months. Again, there’s a lot of logistics that go into determining when this happens. You have to get 30,000 or people or so into a trial. They will be doing these in many states in the United States. They will be doing them in other countries as well. And you have to wait and see just how intense the pandemic is. If you have got people vaccinated in a place where there isn’t a lot of the virus circulating, it’s going to take a long time to see if you have got an effect. So, you actually want to go to the places that are most intense, and there you’re going to see a difference quickly between people who are vaccinated with the real vaccine and who got the placebo.

ISAACSON: I’m in Louisiana, and we’re pretty intense right now. And I signed up for this trial. Was I foolish to do so?

ZIMMER: Oh, no, no. It’s crucial that lots of people volunteer for these trials. Otherwise, we won’t know what works and we can’t move forward. So — and we can only predict so far like where the vaccine is going to flare up and where it’s going to cool down. That’s one of the really amazing things about this pandemic, is, it just — it explodes, it dies out, it explodes again. So, I’m talking to you from Connecticut. We had a horrific problem here in April and May. Now we’re one of the quietest places in the country, for now. We will see what happens in the fall.

ISAACSON: So we talked about the viral vector, the more traditional vaccine. Talked about messenger RNA. And you can also do it with DNA. It’s about the same. Which of them can be manufactured faster and easier and more cheaply if they come out ahead in this race?

ZIMMER: Well, there’s actually a third group of vaccines that really have the big advantage of just a long track record in terms of experience. That is vaccines that are made out of either a weakened version of the virus you want to vaccinate against or just a killed one. And, really, that’s actually…

ISAACSON: Sort of like the old polio Salk and Sabin vaccines?

ZIMMER: Tried and true, yes. And even today, that’s what most vaccines are. There is no licensed messenger RNA vaccine out there for people, none. These — we mentioned the adenovirus vaccines, like the one that AstraZeneca and University of Oxford have. That is just starting to get approved. There was one that was approved for Ebola, for example, just like a couple weeks ago. They have been in research for years and years and years, but the vaccine world moves slowly. So, if you want to think about, well, what would be the kind of vaccine that you could just make in huge amounts, well, actually inactivated vaccines, virus vaccines, or weakened ones, those might be the way to go.

ISAACSON: Now, who’s doing those?

ZIMMER: Well, places like China. So, China actually has two inactivated viruses in phase three trials right now. And so this is really an international story. This is not just the United States doing all the work for everyone. There’s stuff going on in China. There’s research going on in Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, just — India. And a lot are them are looking at these more traditional ones. The downside there is that it takes longer to scale up. You want — it takes longer to make a big batch of these inactivated virus vaccines, because you have to be very careful about it. You can’t rush through it, because you want to make sure they’re really inactivated.

ISAACSON: The United States, I keep reading, has thrown a billion dollars here, $1.2 billion there, to help vaccine development, like with Moderna, or many of the others have gotten federal grants. What do those federal grants do? Do they get paid back? And does that mean we will get the virus more cheaply?

ZIMMER: So, this has been actually kind of a broad trend recently, because vaccines have suffered a lot from what vaccine makers call the valley of death. Some scientists do some work on animals. They see that a vaccine has some promise, and they’re like, OK, now we need some heavy hitters to come in and help us do the clinical trials and do all of the paperwork for licensing and so on. It’s incredibly expensive, and the manufacturing. And a lot of pharmaceutical companies look at it and they’re like, well, I don’t know. Do we think it’s going to work? Or are we just going to lose a billion dollars on this? That slows things down. And so governments and philanthropic organizations for years now have been saying, we need to find ways to speed up this process, for the good of everyone. So one idea is for governments to say in advance, OK, look, we don’t know yet if this vaccine is going to work, but, if it does, we’re going to buy a bunch of them from you. And we will give you some money so that you’re not taking as big a risk on this, and so you’re not going to get destroyed trying to make a vaccine that will help us all.

ISAACSON: And if it doesn’t work, do we get money back?

ZIMMER: No.

ISAACSON: OK.

(LAUGHTER)

ISAACSON: Now, tell…

ZIMMER: You know, the whole thing doesn’t work. If they say, OK, like, you’re going to spend all — you’re going to put — invest all this and take all this risk, and if it doesn’t work out, you give us all of this money back, that’s not going to work for a lot of businesses.

ISAACSON: A lot of the pharmaceutical executives were testifying in front of Congress. Some of them said that they would provide the vaccine at cost. But others, like Moderna, said, no, we’re not going to provide it at cost. And Moderna in particular has been pretty secretive about its approach and has gotten some pushback from scientists. Is there anything that worries you in their approach?

ZIMMER: Well, I think, in general, we need to be a lot clearer on how everybody is going to get this vaccine. If each of us has to pay $100 to get a vaccine, we’re not going to get the kind of coverage that we need. And if Moderna says, no, we’re not going to do this at cost, and won’t even tell us what they’re going to charge for it, we have a problem. And we do especially have a problem, given that the United States government has been supporting their work.

ISAACSON: Are you worried that there is no process and plan for distributing them, for pricing it, for deciding who gets it?

ZIMMER: I certainly have talked to a lot of vaccine experts who have been in this business for years who are concerned that we’re not reckoning with the full scale of this challenge. I mean, there’s a lot of great, stuff again, I should emphasize, in terms of research. The trials are moving forward without sacrificing safety. That’s really important. Like, we’re going to know about the safety profiles of these vaccines, and in lots of populations. But you still have that question of, how are we going to do something we have never done before? And we need a plan now. And, honestly, if you look at, say, where we are with testing, where we’re running out of pipette tips, the most basic equipment for testing, that should make us all very concerned about whether we have our act together enough in the United States to do something far more ambitious than widespread testing. Getting vaccines to people as quickly as possible is going to be a much bigger challenge. If we can’t even get the testing right, which we’re not, then how are we going to get these vaccines right?

ISAACSON: What happens if some people say, I don’t want the vaccine?

ZIMMER: Well, there’s no plans to make it compulsory. Some people have been wondering, if companies will say, in order to work here, you have to get vaccinated. But, you know, that is an important issue, because, in order for vaccines — these vaccines to really be effective on a society-wide scale, we need a lot of people to get them, because, you know, it’s likely that these vaccines are not going to be 100 percent effective. So, just because you get the vaccine doesn’t necessarily mean you won’t get sick. But if 80 percent, 90 percent of people get the vaccine, then it’s going to — the virus itself is just going to become a lot rarer, because it’s going to have a much harder time getting around. And that’s good for everyone.

ISAACSON: At-home tests are being developed by various places, Mammoth Biosciences, Sherlock Biosciences. They like they would be transformative. They would bring biology into our kitchens and they would let us know instant write where we are. Where do we stand with that, and when can we expect at-home tests?

ZIMMER: That’s a great question. I wish it would be, like, today. I wish I can hold an at-home test right here on this camera. It’s very frustrating that we don’t have things yet, because the tests that we’re relying on now use a technology, PCR, which is a great, reliable, powerful technology, but it’s old. It’s from the ’80s. And it requires a lot of ingredients and a lot of careful fine-tuning and such, so you — you can’t easily run a PCR in your house on some little device. But, as you mentioned, these companies, they’re using these new technologies, which you know very well, with CRISPR, where basically you’re using special molecular probes that can zero in on viral genes in a — maybe even just in a spit sample. And the preliminary studies on them are promising. And that sort of thing, a cheap, easy — think of it like a home pregnancy kit, but for COVID. That would change things so much. You just wake up in the morning, take a test, you’re like, oh, my gosh, I have COVID. I’m not going to work. I’m calling in. I’m calling my doctor. We would be so much more on top of this pandemic.

ISAACSON: Tell us where your scenario is for how, over the next year, this movie might end?

ZIMMER: I think now and I think ahead to a year from now. I think that we will have much better treatments for people, so people who do get sick are going to be less likely to die and less likely to suffer lifelong illness. People will be beginning to get vaccinated, so that will help to drive down rates. But I think we’re still going to be making dealing with the virus just a part of our everyday life a year from now. I won’t be shaking hands. I won’t be hugging strangers. I just — it just is something that we’re going to have to be ready to ride through. My big hope, my big, big hope is that we take this experience and get ready for the next pandemic now, that, if we’re not looking forward, we’re going to get caught again.

ISAACSON: Carl Zimmer, thank you so much for joining us. Appreciate it.

ZIMMER: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

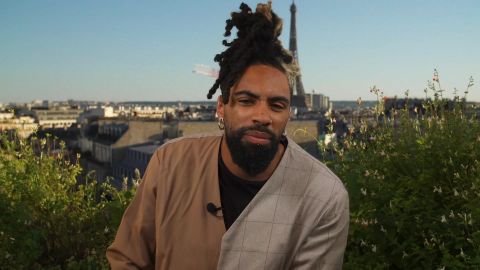

Chrisitane speaks with former Amazon Vice President Tim Bray and scholar Shoshana Zuboff about the pitfalls of the explosive growth of the tech industry. She also speaks with comedian Fary about his Netflix special–the first French comedy special on the platform. Walter Isaacson speaks with New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer about the biology of vaccines.

LEARN MORE