Read Full Transcript EXPAND

BIANNA GOLODRYGA: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

DR. ANTHONY FAUCI, CHIEF MEDICAL ADVISER TO PRESIDENT BIDEN: It’s imperative that we look and we do an investigation.

GOLODRYGA (voice-over): As President Biden calls for a report into the origins of coronavirus, the Wuhan lab leak theory comes under new scrutiny.

I ask Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch why it is so important to get answers.

Then: How will we emerge from COVID? Science writer Ed Yong says tells me why the pandemic’s mental wounds are here to stay.

Plus:

HALA ALYAN, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST: My parents did not end up in Oklahoma because they were fans of Midwestern winters. They went there because — as

a result of a violent dispossession.

GOLODRYGA: As the dust settles on Gaza, Palestinian psychologist and novelist Hala Alyan tells Michel Martin what intergenerational trauma looks

like.

And the Grammy nominated duo Black Violin is here to challenge stereotypes and lift our spirits.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

GOLODRYGA: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Bianna Golodryga in New York, sitting in for Christiane Amanpour.

Coronavirus has upended our world. It was first detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan at the end of 2019 and would go on to claim the lives of more

than 3.5 million people worldwide and infecting 168 million, entire countries locked down, so many lives and economies ravaged.

Yet the origins of the virus remain a mystery. For a while, the possibility of a lab leak was widely dismissed as a conspiracy theory and heavily

politicized, the consensus building around a natural spillover from animal to human instead.

But that seems to be changing, now after a U.S. intelligence report found that several researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology fell ill in

November of 2019. And President Obama (sic) has now requested a report into the origins of the virus.

My first guest tonight is part of a group of scientists calling for a thorough investigation into the origins of the pandemic.

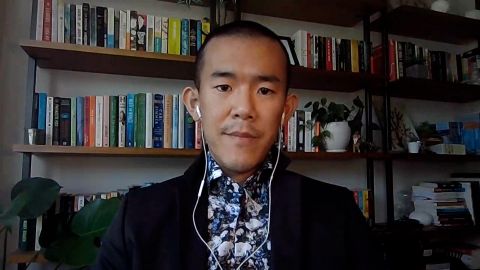

Marc Lipsitch is a professor of epidemiology at Harvard. And he joins me now from Boston.

Dr. Lipsitch, thank you so much for joining us.

I have the letter that you wrote here with some 17 other doctors. And my question to you is why you’re writing this now. Is there more information

that you have come across? Has your thoughts and opinions as to the origins changed over time?

DR. MARC LIPSITCH, HARVARD UNIVERSITY’S T.H. CHAN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH: I think that, as time has gone on, the pandemic has stretched our notions

of time in all sorts of ways.

But I think it has become more apparent to many of us that the investigations that had taken place, and specifically the World Health

Organization investigation, just wasn’t answering the question adequately.

And we wanted to, in a very balanced way, say that we don’t know what the right answer is, but that this question is still an open one and needs to

be answered as best we can.

GOLODRYGA: Yes, the World Health Organization report really focused more time on a natural spillover and spent little time, just a few pages of that

report, focus on the possibility even of a lab-based disaster and origin here.

Talk about China’s role since the beginning, because they have tried to clamp down on that theory from the get-go. And a lot of this has led to

politicization and even racist commentary towards China.

But how would you view and weigh their participation and their role from a scientific standpoint in helping to find the origins?

LIPSITCH: Well, I think — I think China is a big place, and there’s the government and then there are individuals.

And I want to emphasize that a number of individual Chinese scientists and physicians were truly heroic in the beginning of this pandemic in getting

the word out to the world, as well as to the rest of China.

And, obviously, there’s no place for any racist or anti-Chinese sentiment in general. However, the government indeed has not been forthcoming with

information that would answer — help to answer the question or to — or lay to rest the concerns that a laboratory accident is one possible

scenario under which this could have happened.

GOLODRYGA: And part of this has been politicized throughout the Trump administration. Early on, we should note that he said he supported China

and that he trusted President Xi and their exchanges in early 2020.

That, of course, changed, and President Trump continuously said that he did believe that this was the creation of something in a lab and would not get

into specifics.

As I mentioned earlier, it was President Biden who just this week said that he would like an investigation into the origins. What do you make of the

change here? Because there had been some sort of consensus, at least among the general population, general public, that things were more likely

leaning toward natural spillover.

Why do you think things have changed over the past few weeks?

LIPSITCH: Well, I think that, with the change of administration and with calls even before today from this administration, and from European

leaders, and indeed, from the director general of the World Health Organization the day after that report was issued, it really is not a

fringe theory.

I mean, people can debate whether it requires a conspiracy to cover up something like this, or whether it’s — or whether it’s not a conspiracy

theory — I don’t want to get into the terminology — but it had been viewed as a fringe theory because it was espoused in fringe ways by some

people with political agendas.

And I think, at this point, the — it’s taken some time. People have been focused on dealing with the consequences of the pandemic, but a few things

are clear. One is that the natural origin has not been documented. And that may be hard to do. It may be — turn out to be impossible to do. But we

need more efforts to try to trace that possibility.

And the other, I think, is that many people had focused on the sort of most negative of the possible laboratory scenarios in which research that should

not have been done was done, maybe with ill intent, and then there was a cover-up, and this was a human-created virus.

None of that is fully required for the laboratory origin. I would say the most likely way it could have come from a laboratory would have been from a

sample of a natural virus that was being studied for perfectly good reasons in the laboratory.

So, you don’t have to…

GOLODRYGA: Yes, from an accident.

LIPSITCH: Yes, from an accident, and not necessarily from an accident with an engineered virus.

That is one possibility. But there are many more innocent possibilities also. And I think the politicization has meant that people had a hard time

for a while separating accusations of misconduct from the possibility of an accident.

And we know that laboratory infections occur in laboratories, including with SARS viruses.

GOLODRYGA: Right.

And I know that public health officials like you and those in the medical community are not used to sort of being in the midst of a political

scandal. You focus on the science. But, in terms of politicians, there had been many in the United States, particularly within the Republican Party,

who had been going down this route that this was the cause of something that went badly in a lab, and perhaps it was nefarious, perhaps it wasn’t.

I want to raise Senator Tom Cotton’s tweets recently. And he tweeted out four possible theories, four possible scenarios for what happened. One is

natural, that it just came evolved from animal to human. Two is good science, bad safety, which is I think what you just alluded to, three, bad

science, bad safety, so ill intent and poor safety, and, four, just deliberate release, intentional.

Out of those four, you seem to think that it’s either A or B, right, natural, or good science and bad safety?

LIPSITCH: That’s right.

And I think — well, I’m saying that those are at least very possible, and that I don’t know how to put weights on these. I think the lack of evidence

is so — the evidence is so lacking that putting weights on the different possibilities is hard.

But it is important to say that we can imagine an accident that does not involve ill intent. Those have happened in the past, not with pandemics as

a result, but with infections and transmissions as results. And we should expect that that’s a possibility.

GOLODRYGA: And we heard, though, the range of possibilities from Tom Cotton, who is not a doctor, not an epidemiologist like yourself. He is a

politician.

But there were also those in the medical community. The former head of the CDC also raised eyebrows when he suggested in his own opinion from his old

medical training that it was at least worth exploring a lab-based release.

Let’s listen to what he told our Dr. Sanjay Gupta earlier this year.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DR. ROBERT REDFIELD, FORMER CDC DIRECTOR: I am of the point of view that I still think the most likely etiology of this pathogen in Wuhan was from a

laboratory, escaped.

Other people don’t believe that. That’s fine. Science will eventually figure it out. I do not believe this somehow came from a bat to a human,

and, at that moment in time, the virus that came to the human, became one of the most infectious viruses that we know in humanity for human-to-human

transmission.

It’s just too hard for me to go from bat to me to the most infectious human pathogen. Normally, when a pathogen goes from a zoonotic to human, it takes

a while for it to figure out how to become more and more efficient in human-to-human transmission.

I just don’t think this makes biological sense.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: So, he doesn’t think that makes biological sense. What do you make of his theory?

LIPSITCH: With all due respect, I think that’s nonsense.

I think SARS-1 did exactly that. And we have from probably bat through civet to human, and had — that was comparably contagious to SARS-2. That

was in 2003. And so we know it can happen. And influenza viruses sometimes do the same thing through other animal hosts.

So, that’s just not — I don’t understand the logic behind that.

GOLODRYGA: So, for those of us at home trying to digest all of this as we have been coming out now after over a year of just hellish headlines, and

the death and the loss and the toll has been enormous, for those that may be asking, why does it matter, why should I focus on the origins here,

let’s just work on the vaccines and getting more people vaccinated and move forward, what is your response to that?

Why is it so important to know where this virus originated? How do we get to that science?

LIPSITCH: Well, I must say, I’m sympathetic to that view. And, in fact, having spent a lot of years in the past on the science policy issues of

laboratory safety, at the beginning of this pandemic, I made a conscious decision to focus on what we can do about the problem, not about the

origin, and to come back to this question at a later date, and did so.

But I think that the — that, for exactly the reasons you say, we need to – – we deserve, as a global community, an honest effort to find out what just hit us and why it hit us. I think it’s one of the biggest events in the

last half-century in terms of world history.

And we should know why it happened. That’s just a human need to know. But, beyond that, I think pandemics are very rare events. They happen a few

times per century. And understanding how they happen means that we can prioritize our efforts to prevent them in the future.

And if — and a single event out of a few per century is a meaningful number. So, we only have a little bit of data to work with. So, if it came

from a laboratory, that argues for a number of efforts to increase laboratory safety, revisit the kinds of work that gets done in laboratories

and which laboratories it gets done in.

If it came from an animal, we need to focus on preventing animal spillovers and detecting them early.

GOLODRYGA: Yes, well, we continue to hear, and we repeat in the media industry ourselves, we repeat, follow the science, we’re following the

facts, we’re following the science.

And I guess it really is difficult to do that, if you don’t know the exact origins and where this came from, to prevent another, God forbid, pandemic

in the future.

I want to just end on something that you wrote in your last paragraph here in your letter, because you said: “In this time of unfortunate anti-Asian

sentiment in some countries, we note that, at the beginning of the pandemic, it was Chinese doctors, scientists, journalists and citizens who

shared with the world crucial information about the spread of the virus, often at a great personal cost.”

Why was it important for you to mention that at the close of your letter?

LIPSITCH: Well, for the reason that I said at the beginning, that the last thing we wanted to do in calling for an impartial and scientific

investigation was to feed the negative, in some cases, deadly negative sentiment that has grown up, anti-Asian sentiment that has grown up or

anti-Chinese sentiment that has grown up.

There are a lot of politics here. That was not our issue. But we wanted to at least try to point out that calling for investigation is very different

from condemning an entire group of people.

GOLODRYGA: Absolutely. And we remember those doctors.

The one doctor comes to mind who actually died just a few weeks after he warned the world in China about the virus, and President Biden obviously

issuing this investigation, wanting to get to the bottom of it.

And he just said today that he hopes to disclose as much as possible when those results are in.

Dr. Lipsitch, thank you so much for your time. We really appreciate it.

LIPSITCH: Thank you for having me.

GOLODRYGA: Well, we turn now to the road ahead and the next big question: How will we emerge from the pandemic?

Ed Yong is a science writer at “The Atlantic.” And he’s been chronicling the outbreak extensively. In his recent piece, he looks at the pandemic’s

mental wounds and asks: “Things are getting better, so why don’t they feel better?”

Ed Yong is joining me now from Washington.

Ed, thank you so much for coming on. We are all big fans of your work here on the show. And I think this piece was just perfectly timed. And it comes

when we’re having so many other conversations collectively as a nation, as things are starting to get back to normal, at least here in the United

States, going back to work, going back to school, summer camps, what have you.

We’re hearing a lot about logistics, right? We’re not necessarily hearing about how we come back emotionally. Why was it so important for you to talk

and delve into this issue here?

ED YONG, “THE ATLANTIC”: I had heard from so many people that they were excited about getting back into the world. I think we have all been looking

forward to this moment for the last year-and-a-half.

But they expected to feel great and actually were hitting a wall. A lot of them were feeling — are more upset than they had been for the last year-

plus. And when I talked to experts who study trauma and how communities deal with it, they said that this is common, that this is actually very,

very, very common.

So, people often, when the adrenalin calms down and they get a chance to recollect themselves, they get moments to reflect on everything that’s

happened to them. And those reflections can be deeply painful. They finally get a chance to actually understand how hard and difficult and full of

stress and hurt the last year-plus has been.

And that can be very damaging, especially if you’re not expecting it to take such a toll, at a moment when you feel like you should be joyful.

GOLODRYGA: And you encapsulate that so well in this one sentence in the piece: “If you have been swimming furiously for a year, you don’t expect to

finally reach dry land and feel like you’re drowning.”

And yet so many people are at that place now. They’re at the dry land. They have made it. They have been vaccinated, but they have been through hell.

And, for many, it still feels as if they’re still grasping for air in the ocean.

YONG: Yes, absolutely.

A lot of people I spoke to said that, often, even incredibly hypercompetent people who are used to dealing with a very regular amount of daily stress

are finding this moment hard, and, again, confused because they’re finding it hard. That could be anyone from teachers, parents, to health care

workers, doctors and nurses, people who are very used to handling adversity, but are still struggling with the aftermath of everything that

we have gone through.

And that could be things ranging from the death of a loved one, to the loss of a job, through just the constant levels of fear and anxiety and

uncertainty about our future that have overwhelmed us for the last 14 months.

GOLODRYGA: And you have spoken to a lot of experts here throughout this piece.

And, for them, given their expertise, and they have been in this industry for so long, they still struggle with defining some of these terms, like

trauma. What does trauma mean? And you talk — and you break it down to trauma with a capital T and trauma with a lowercase T, those, I guess, that

have been directly impacted.

Maybe they had survived COVID after being in the hospital for many months, and those that had been the first responders and the doctors and nurses,

and then perhaps those that have just been absorbing it all and not being able to cope well.

YONG: Right.

That’s — the official psychiatric definition of trauma, that big T definition, is a little bit restrictive, because of this debate about

whether the term is being overused and all.

But I think, even if you’re dealing with little T traumas, which can actually include some massive things, like divorce, loss of a job, like, if

you pile all those things up for months on end, you’re going to rock people’s mental health. And that’s what we’re seeing now.

I think some people will be fine. And if you’re in that boat, I feel extraordinarily happy for you. But a lot of people won’t. A lot of people

will still be struggling with grief, with loss, with stress that they haven’t — haven’t even had a chance to voice. And that is going to take a

long time to recover from.

It’s not just the case that you get a vaccination and you snap back into perfect mental health. And we need to have space in our hearts and in our

societies for people who are still going to take time to struggle with the lasting impact of this crisis.

GOLODRYGA: It’s laughable at the start of this crisis some referred to it as a great equalizer, because it was anything but.

You had sections of the community and pockets of the community that were impacted in ways many others couldn’t even imagine, particularly the black

community and the Hispanic community. And you have trauma on top of trauma over this year. It wasn’t as if we all lived in a bubble. We had murders,

police murders .We had George Floyd. We had protests.

You talk about that sort of collective trauma, trauma building on itself on itself on itself. What are the consequences of that?

YONG: I think it all exacerbates. So, every one of the dynamics that I have just spoken of will be even more keenly felt by people who’ve endured

a disproportionate share of the grief and the trauma from the last year.

And it’s not even just the last year, right? It’s not as if these communities were on equal footing before the pandemic happened. Indeed,

it’s the structural inequities that have left them with poorer health, with less wealth.

That meant that they were more likely to be infected by and killed by the virus. And, as you say, all of the stresses of the pandemic layered on top

all the other crises of the last year and more. And I think that that is going to — those inequalities are going to continue being a problem moving

forward.

It’s like grief from the pandemic will germinate along the very same lines that the pandemic found and widened in our society. And this conversation

about making space for people to grieve and deal with loss is also one that necessarily must have equity at its core.

We must — we must make special — we must give extra care and attention to people who’ve been disproportionately affected by this pandemic and all the

health inequalities that preceded it.

GOLODRYGA: Another term we have heard a lot over the past year-and-a-half is unprecedented, right? And that’s where we were.

I mean, unlike previous disasters and crises, traumatic events — I think back to 9/11 — this one impacted every single age group, every part of the

population, whether they were directly sickened, and whether they knew someone who was sick, whether they lost their job or their business,

whether 5-year-old kids could not go to school.

In terms of the experts that you spoke with, how did they themselves come to a place where they could be of help and know how to respond to some of

the grief and the anxiety that they were hearing from people?

YONG: Yes, that’s a fantastic question that I think we don’t talk enough about.

A lot of the caregivers and the people who — like the guardians, the people who are meant to protect us and look after communities who are hit

by crises are doing really badly, because they, in particular, really have not had a chance to take a — catch a breath.

Many of us, many of the rest of us may have vaccines and may be going out and enjoying — quote, unquote — “normal life” again. But people who work

in areas of emergency preparedness, a lot of health care workers are still stuck with dealing with pockets of unvaccinated people or dealing with

areas where the pandemic is still surging, dealing with the global nature of the pandemic, countries that are still being pummeled by this virus.

Their watch over the rest of us won’t end in — any time in the near future. And that worries me considerably, because we need their strength,

their mental strength and their resolve to safeguard us against future disasters, which we know are coming. This is not going to be the last

pandemic, I’m sad to say.

And in the coming months, we’re going to enter hurricane season, wildfire season. We need the people who protect us to keep on doing that job. And I

worry how much more of this they can tolerate.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

And you talk about the pandemic still being with us. I mean, 4,000 people at least are dying every day in India. It is definitely still ravaging

large pockets of this country.

In terms of PTSD, you note that 30 percent of people in Italy, according to one study, suffered from PTSD following their waves there. And we remember

covering them here. It was just death after death, unprecedented images that we had seen out of Italian hospitals.

From a U.S. standpoint, are the numbers that you found similar? I mean, it’s interesting to think about how each country sort of responds to a

crisis, maybe in a different way, maybe not.

YONG: Yes, I’m worried about that.

I’m not sure we have great stats yet for exactly what to expect with the U.S., but let’s just take a few simple numbers. We have had 600,000 deaths

also. We know that each death leaves an average of nine bereaved people, which makes around — just under six million people grieving loved ones.

We know that around one in 10 people who are bereaved go on to develop prolonged, complicated grief. So, even a year after, they’re still

overwhelmed by intense grief that doesn’t seem to be abating.

If you put those numbers together, that’s the population of something like Atlanta, right?

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

YONG: So, that’s a city’s worth, a large city’s worth of people who are going to be struggling with intense grief in 2022.

And we simply don’t have the mental health infrastructure to care for all of these people. And that’s not even thinking about the other sources of

trauma we’re talking about, the other forms of reaction to the stresses of the last year.

And I think what’s crucial to remember in the United States is not just is that — what’s different about the pandemic than other disasters is,

unlike, say, a hurricane or a terrorist attack or anything like that, it doesn’t just happen and then stop. This has been with us for 14-plus months

now.

And it has just been this collective, rolling cascade of separate disasters that have hit one off to the other.

GOLODRYGA: Right.

I remember, early on, we were covering it is as that this is 10 9/11s, this is 20 9/11s. I mean, you’re sort of putting it into some kind of context

when you see the numbers, which were just astronomical and something we’d never seen in the United States of America.

Let’s talk about solutions and move ahead, because your experts did offer some solutions for you. And they said, when many patients would come to

them and say, I don’t want to talk about this anymore, what should we do, the recommendations were the best way to deal with this, and especially

another pandemic, another crisis, is preparedness.

The significance of preparedness, from a personal household level, to a government level, which we clearly were not there when this pandemic hit,

that really is the key to at least diminishing some of the consequence that we’re still seeing impacted now.

YONG: Yes, the whole concept of public health is about safeguarding the health of communities and stopping them from getting sick in the first

place.

That’s really what we should be doing. And, instead, America’s response focused very much on the people who were the very sickest. We don’t have

this ethic of, like, looking after the health of people in the communities in this collective way. We sort of leave people to fend for themselves.

And I think that is very costly. We know, from experience with past big traumas, that communities do better if they have better solidarity, if they

have a sense of belonging, and if they have trust in authorities.

And, obviously, the pandemic in the U.S. eroded all three of those things. But we can get some of that back. We can certainly get a sense of

solidarity back if we try — make efforts to look after each other now. And I don’t think that that should be — the onus of that shouldn’t just be on

individuals, right?

It’s not all of us to meditate our way to better mental health. The onus should be on better structures to look after people’s mental health.

Employers should make space for the employees to actually take time off, to get the help that they need.

And the country, while it thinks about rebuilding from COVID, needs to put an emphasis on accessible, widespread mental health provisions for its

people.

GOLODRYGA: Well, Ed, I know that you have also spent this time not only educating us — and, at least, for me, I felt as if you were kind of

holding my hand throughout this process. I turned to your work on many occasions throughout these past 14 months.

You have been working on a different project as well. And that’s writing a book about how animals see the world around them. We can’t wait to hear

more about this book and read it.

But just let me ask you as we end here, on a personal note, did that help you? Did the research and the work on that book help you in any sort of

coping that you were experiencing during this time?

YONG: It did help. It was nice to not think about the pandemic for a while. I also got a puppy while I was writing about animal sensors. So,

that — there was a nice — there was a nice overlap there.

But part of why I wrote this piece is that I experienced this myself. When I finished the book and finally got a chance to grieve, my first, like,

week off since the pandemic first started, I found it really hard.

I really struggled in ways that I couldn’t understand. And talking to the experts I talked to for this piece, working through it myself helped me to

understand how I was feeling at a time when I theoretically should have been feeling much better.

So, if you’re in the same boat, if you feel off, if you feel a little lost, if you don’t understand why, you’re not alone.

GOLODRYGA: Well, that is encouraging to hear.

Also encouraging to hear that you have a love for puppies. And, hopefully, that cute little puppy helped you and put a smile on your face as well

throughout this time.

Ed Yong, thank you.

(CROSSTALK)

YONG: He did. He is a corgi. His name is Typo.

GOLODRYGA: What is his name?

YONG: Typo.

GOLODRYGA: Typo.

Well, we can’t wait to see pictures of him.

(CROSSTALK)

GOLODRYGA: Send them — send them our way.

YONG: All right, will do.

GOLODRYGA: Thank you so much, Ed Yong.

YONG: Bye.

GOLODRYGA: We’re going to continue our conversation now on trauma and we’re going to turn to Israel and Gaza. A week-long cease-fire may have

silenced the bombs but the psychological scars from the decades-long conflict remain. Hala Alyan is a Palestinian-American writer and

psychologist who focuses on the impact of generational trauma. Here she is speaking to Michel Martin about how her experience as a Palestinian abroad

has inspired her work.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Bianna, thank you. Dr. Hala Alyan, thank you so much for talking with us.

HALA ALYAN, AUTHOR, “SALT HOUSES”: Thank you for having me.

MARTIN: You are a clinical psychologist and a writer of poetry and fiction. You’ve written some remarkable and critically acclaimed work about

people of the diaspora. We are speaking a few days after the bombing of Gaza and the air strikes directed at Israel have ceased under a negotiated

cease-fire. And I’m just wondering what these last few weeks have been like for you?

ALYAN: It’s been devastating. I mean, I think it’s been devastating for all of us that are in the diaspora with the understanding and the caveat

that it in no way compares to the devastation that people on the ground are experiencing in places like Gaza, but it’s been heart wrenching, and I

think it’s also important to note that for a lot of us, we’re aware that these — you know, a lot of these policies and this oppression and this

occupation is something that’s ongoing. It’s happening. Like there’s a cease-fire right now and that’s very welcome come, but there isn’t a cease-

fire on the human rights violation, there isn’t a cease-fire on the apartheid policies. And so, I think it’s really important to kind of keep

talking about this even when there is an active bombing.

MARTIN: I want to tap into both of your identities, as we mentioned, both as a therapist and as a writer and a storyteller. Like the first thing I

wanted to ask you as a therapist, what concerns you most about what’s just happened? I mean, we know that about a dozen people were killed in Israel.

We also know that more than 200 people were killed in Gaza including 60 children that we know of at this moment. What is the effect of an

experience like this?

ALYAN: Yes, I mean, you know, I’m going to quote the Palestinian psychiatrist, Samah Jabr, who spoke really beautifully and wrote really

beautifully about this idea that the concept of PTSD stands doesn’t really apply to a lot of Palestinians. PTSD stands for post-traumatic stress

disorder. She makes the point quite effectively that there is no post for most Palestinians.

Trauma, in order to heal from trauma, one requires reprieve. And at the end of the day, the conditions that birth trauma for Palestinians endure in

periods, even the periods that the outside world considers to be cease- fires. And so, you need reprieve not just from the conditions that made the trauma that you’re in currently, but you need reprieve from future trauma.

And so, I mean, one of the things that comes to mind is the gut-wrenching story of the 11 children killed a by Israeli air strikes were actually in a

trauma program led by the Norwegian Refugee Council. So, these are children that were already being treated for trauma that were killed in their homes.

And so, when you have a situation where children who are already traumatized don’t have a sense of safety and security in their homes to

access that reprieve for healing, I mean, I think that says a lot about where we’re at in terms of trying to create the conditions for actual

recovery from trauma.

MARTIN: Part of your fiction, at least one of the books that we want to talk about today, “Salt House” is your — an award-winning novel published

in 2017, sort of deals with the experience of diaspora, of being perpetually displaced. But it also deals with the ongoing — the day-to-day

experience of living both here and there. And I’m interested in also the people in your extended network who don’t live in Gaza. How are you

experiencing this? Is this something that they can kind of — that they are living too?

ALYAN: Absolutely. I mean, I think, you know, we can have the conversation of sort of the trauma that’s experienced by folks and (INAUDIBLE), the

trauma that’s experienced by Palestinians with Israeli citizenship facing apartheid policies, the trauma that’s faced when you have Palestinian

cities that can’t access each other because of checkpoints. But there is absolutely also the trauma of erasure that you find within diaspora

communities.

There’s the trauma of — you know, I think there’s a way in which sometimes we think about diaspora as something that kind of gets nostalgic and

sanitized and its sort of like looking at the (INAUDIBLE) through a pane of glass, but the reality is that diaspora doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Diaspora

is the result of violent dispossession.

And so, I think, for a lot of us in the diaspora, as we’re watching this, we are being reminded of the fact that we are, in many ways, very much the

lucky ones. And I want to be very clear about that, right. I am in Brooklyn right now. I am relatively safe. But even to be a lucky one, still at the

tail end of a fair amount of violence and dispossession, my parents did not end up in Oklahoma because they were fans of midwestern winters. They went

there as a result of violent dispossession.

My grandfather’s — my grandparents — maternal grandparents, (INAUDIBLE), was virtually wiped out of existence, you know. And so, I think, for a lot

of folks in the diaspora, we’re watching the Senate sort of — it’s very much a reminder of what our families have already been through.

MARTIN: You know, I’ve had the privilege of interviewing a number of Native American writers and when I asked them what they most want other

people to know, very often they say that we’re still here.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: And your award-winning novel “Salt” has a centrist (ph) on the experience of a Palestinian family through four generations. Would you just

tell us a little about it for people who aren’t familiar with it?

ALYAN: So, it starts in pre-’67, in Nablus, and it centers around a family that has already been violently dispossessed from Jaffa and ended up and in

Nablus. And then post the 6th day of in ’67, they end up in Kuwait. And then, after Saddam’s invasion, which is unfortunately a story that a lot of

people in other countries are familiar, with this idea of multiple displacements. They are displaced once again. And at this point, the family

kind of becomes scattered all over the globe.

And so, the story is, like you said, over four generations, different family members speaking at different points in time and kind of, you know,

just trying to kind of have lives in the midst of diaspora.

MARTIN: We’ve only, I think, recently as just the general public started talking about how experiences even generations ago can influence you in the

present day.

ALYAN: Right.

MARTIN: I’m thinking about in your novel, “Salt Houses,” I am thinking about Salma, the matriarch, and how the decisions that she makes for her

family, for example, sending one of her daughters — or rather consenting to a marriage for one of her daughters that will send her far away saying

she knew she would be safe in Kuwait, her unhappiness, if it came, was worth the price of her life.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: Is that something that you think is a common experience of the people that you think about and write about part of your life? The sense of

constantly having to make that tradeoff?

ALYAN: I think at the end of the day, when we talk about diasporic populations — and I want to be clear. I think sometimes folks leave their

home band voluntarily, right? They leave because they’re looking for like a future. They want to study abroad and whatever. And that’s very, very

different than violent dispossession. I want to just make that distinction.

So, when speaking of the latter, you know, I think that absolutely what ends up happening is that folks within those populations are — there is

often a deeply felt sense, even if it’s several generations back of the world being flipped on its axis. And there — and this is what trauma is at

its core, right? Trauma usually kind of splits the world into pre and post, like before and after. Where — for people who have a single defining

events of trauma where there’s kind of the sense of like the world is no longer to be trusted, the world is no longer to be seen as safe.

You’re not sure even — if there are periods of stability or periods of quiet in your life, in your personal life, you’re not sure that you can

trust that. And so, that manifests, I think, in a lot of ways in hypervigilance, in a constant feeling that waiting that the other shoe is

going to drop and a constant sort of obsession with safety and how to have some semblance of control in a world that has already proven itself to be

way beyond the (INAUDIBLE) control. So, I definitely that’s something that’s true for a lot of folks.

MARTIN: Most of the book is told through the eyes of women, and they are left to internalize and imagine the horrors experienced by the men.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: There’s a horrifying scene, though, I think one of the most disturbing in the book is narrated by a man. It’s about the rape of his

sister. You are left to assume that it is by Jewish insurgents or soldiers trying to intimidate the family into leaving, but it’s described sort of

elliptically, almost as if it could be a buried memory or it could be a borrowed memory, and I was wondering why you chose to describe that scene

in that way?

ALYAN: I think that I really — as a clinical psychologist, one of the things that you often see when we talk about trauma and memory is that

trauma fragments memory that we talk about the way that people who have been traumatized or have experienced chronic trauma is that it does stuff,

it shifts something in memory.

So, you know, when you experience something traumatic, you’re (INAUDIBLE), right? And so, in some ways, the memory can be incredibly vivid and you can

remember, very, very, very specific details, but at the same time, there’s a lot of self-protected mechanisms in our ecosystems that can shut things

down. And so, you will hear people, for example, who are survivors of sexual assault talk about kind of blocking out or leaving their bodies or

sort of like disassociating.

And I think that there is this way in which I — when I write about trauma and traumatic memories through characters, and, frankly, in my own life and

my own mom fiction, I do think it’s important to thread the needle between this way in which some things are really, really, really clear and like

incredibly vivid and then also some things the system shut down to protect you.

MARTIN: We are in a really polarized moment. It’s very hard to have conversations about a lot of things in this country, as well as around the

world. And I’m wondering like how — if, in part, this was a distancing to allow people to say, maybe this happened, maybe this didn’t happen this

way, but we can still talk about it?

ALYAN: No. I mean, I — those experiences of sexual violence did happen and it’s been recorded by historians. It is very important to be able to

name experiences and put language to them. These things that happened didn’t happen to that character. That character is a fictional character

but there are (INAUDIBLE) who did happen.

MARTIN: OK. I’m just saying that I find — I think that people will find that very shocking.

ALYAN: Look, I wrote a story about a Palestinian family, and you can — I am sure you can imagine how airtight my sources had to be when I was

writing it and how carefully I had to do research and to make sure that I did not write about anything that was not documented by both the primary

and secondary sources. So, I think there’s that.

I do think it’s really important for us to all have conversations about the narratives that we have and the stories that folks get attach to. I think

that in this country, there often is — folks are exposed to certain stories and certain narratives about Palestinians, about Israel, and being

about this Israel as a government, Israel as an entity, Palestinians as a people. There’s a lot of erasure. There’s a lot of — if you look at the

media and there’s a lot of — even the depictions of like the dead are different, you know. It’s one — like people get killed versus people are

dying. There’s like — there’s a lot of analysis that’s being done right now around sort of the language use and headlines when we’re talking of

death in Palestinian communities.

There’s a lot of neutral language like clashes or war that implies parody in armies as though there are, you know, two equal armies that are in

conflict with one another. And I think it’s — listen, I have no ill will towards anybody who has not been exposed to different narratives for their

attachment to the narrative. But what I do ask, which I think is the reasonable ask, which I think is very similar the ask that many people that

belong to marginalized identities have, is to educate themselves, because I think, you know, at the end of the day, history is there for anyone to open

a book and engage with it.

MARTIN: One of your specialties is trauma, and of course, you know, American Jews or Jews all over the world still carry the trauma of the

holocaust, as well.

ALYAN: Sure.

MARTIN: And how do you think about that?

ALYAN: Yes. I mean —

MARTIN: I mean, is there a way in which their discussions around the holocaust have, in a way, made some space for other people to talk about

their experiences of intergenerational trauma? What do you think?

ALYAN: When I talk about sort of standing for and fighting against persecution, that applies to everybody, so that absolutely applies to folks

who have been — are sort of the descendants of holocaust survivors, that involves standing up against anti-Semitism, that involves standing up for

black lives. So, I believe that any community that’s been persecuted as many Jewish communities have been are absolutely part of this conversation

of intergenerational trauma.

MARTIN: But I’m just curious, like how do you think about the fact that so fundamental to the way American Jews think about Israel is so connected to

how they think about holocaust as a refuge for — from the holocaust and as a way to offer safety and sanctuary for people who have been so viciously

persecuted not just in that era but throughout centuries? I realize it’s a difficult and a heavy topic, but how do you integrate those parallel

realities?

ALYAN: So, I start separating (INAUDIBLE) Judaism, which I think is really important and which I think a lot of like Jewish community leaders and

Jewish organization, including Jewish voices towards the (INAUDIBLE) have been very precise about. I think it’s really important to make it clear

that holding a state or a government accountable for their human rights violations has nothing to do with anti-Semitism. It has nothing to do with

speaking against Jewish communities. And I think the Jewish voices that have actually been really beautiful and essential in the Free Palestine

Movement are all the evidence I need for that, right?

So, for me, they — I think that it’s really important to think of the Free Palestine Movement as part of a broader collective struggle against

oppression, against persecution. So, I do not — that includes anti- Semitism.

So, for me, I do not think that these things are contradictory. I don’t think that — I don’t think of it as you stand against anti-Semitism but

you also are for free Palestine. I think of it as, you stand against anti- Semitism because you are for free Palestine. So, for me, they are not in any way contradictory. They absolutely are hand in hand.

MARTIN: But what I’m asking you is how you think about people reconcile their realities which are both true, which is that people have a historical

experience of oppression which leads them to a certain place and a certain understanding of the world and a certain desire which conflicts with the

desires and historical experience of other people. That’s what I’m asking you.

ALYAN: I mean, I don’t know that it conflicts with it. I think at the end of the day, and this was captured eloquently in the report that was

published in April of this year by Human Rights Watch. At the end of the day, what we’re talking about are apartheid policies by the Israeli

governments that speaks to the survival of the democracy as a Jewish democracy being predicated on the erasure of Palestinians. So, that really

feels very different than talking about having a place that’s a safe refuge for everybody.

What I think people are advocating for is quite simple, a place where everyone lives alongside each other with equal rights. And to be perfectly

frank, the barrier to that will always be occupation, it will always apartheid policy and it will always be ongoing violence possession. That is

the barrier to everybody living with equal rights alongside each other.

MARTIN: You kind of grew up with parallel discussions, if I can put it this way. There were discussions that I think people who have — who were

Palestinians have had — have been having for generations that have not always been as much — a part of the mainstream political public general

discussion as they are now. The question of the database circumstances of Palestinians. Do you feel like, you know, where you kind of sort of fight

for that story to be told?

ALYAN: Yes. I definitely think so. I mean, I think —

MARTIN: And what do you think has made the difference now?

ALYAN: You know, I go back to this idea that I think the intersectionality, discourse around intersectionality of social justice

movements has been crucial. I think that when you see BLM issuing the statement of support for Flee Palestine, when you see people on the street

that are marching for these protests belong to various indigenous folks from this land, belonged to our Jewish brethren, our Jewish kin, when you

see people rising up together, I think that we are at a moment when we’re realizing — we’re having a reckoning, I think, in this country, as in a

lot of places, where we’re starting to realize that you do not get to pick and choose whose human rights you fight for.

You do not get to choose whose human rights are more worthy over the others. That if we rise, we rise together. And that the offer to stand with

persecuted and oppressed people to not be conditional.

AMANPOUR: Doctor Hala Alyan, thank you so much for talking to us.

ALYAN: It was my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: A really important and informative conversation.

And finally, if you ever wondered what might happen when Bach meets Biggie Smalls. Well, we give you the Grammy nominated duo Black Violin. A

classical hip-hop hybrid. They began their musical journey in the classroom, experimenting and pushing the boundaries of genre.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: Their mission, smashing stereotypes and assumptions about race through their art. Kev Marcus and Wil Baptiste join me now live Fort

Lauderdale, Florida.

Guys, thank you very much for joining us. We’ve been looking forward to this segment all day.

First, let me begin by asking how you — I know you went to high school together, but how did both of you find each other and your mutual passion

for classical music?

KEV MARCUS, MUSICIAN, BLACK VIOLIN: Well, first day at high school, we were stand partners in orchestra class. That’s how we met. So, in a way,

you know, we always had instruments in our hand. We just study — we study classical music, yet, we lived hip-hop. And for us, it just was really

natural for us to put it together. So, I guess that’s why 30 years later, we’re still standing here doing this. So — but it’s been an amazing ride.

GOLODRYGA: And you’re making incredible music. And, Wil, I was watching an interview with you earlier and you would describe people coming up to you

and saying, you? You played the violin? You like classical music? Why are there certain stereotypes and barriers to more black musicians turning to

classical music like the violin?

WIL BAPTISTE, MUSICIAN, BLACK VIOLIN: I think a lot of it had to do with just like society puts us in boxes. You know what I mean? Like, look like

me, I look more like a basketball player. He should be playing for the Dolphins or something. You know what I mean?

So, I think that we’re — that’s what happens in — throughout the years, you know, for us, that’s what we try to do and try to — when we talk to

kids, we try to get them to understand, listen, you’re more than whatever this box that society tries to put you in. You know what I mean? With our

foundation and everything, we really try to really, you know, implement that idea that you can be wherever you want. It doesn’t matter what it is,

you know, classical music has been around for 400 years and we’re able to do something very, very cool and different with it, you know.

GOLODRYGA: And pushing boundaries as well because you also say what you play and what you perform is true to classical music. What has the reaction

been from other classical musicians?

MARCUS: A lot of classical musicians just love that we’re pushing the art form forward. You know, we’re disruptors. So, with anyone that’s doing

something disruptive, some people may kind of pushed back against it, but we find that it’s been amazing. You know, a lot of new people, new young

people are exposed to classical music now because of us and we blended together in a way where we’re very respectful of classical and we’re also

very respectful of hip-hop.

So, we put it together in a way where it’s a really, really well- proportioned cocktail, so to speak. So, you know, it’s just like, if you’re into classical, close your eyes and listen to the classical part, and if

you’re into the hip-hop, you just nod your head be like, oh, man, you know? So, it’s just by putting them together in a really kind of organic way,

we’re able to cast the widest net and be able to bridge the gap, so to speak.

GOLODRYGA: And it works so well. I mean, I think back to the initial cast of “Hamilton,” right, and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s idea of putting it to hip-

hop and people being puzzled, how is this going to work. And yet, you see huge success and the audiences that that has reached that it probably

wouldn’t have been reached had it been performed any other way.

You’re moving forwards and you’re putting it forward ahead. You are really trying to get younger generations, and particularly black children and

black musicians to delve into this area as well. The Black Violin Foundation. Tell us about that.

MARCUS: Yes. So —

BAPTISTE: So, yes. So, the Black Violin Foundation. And that’s our goal, man, because we understood how important it was and representation is

important, you know, growing up, playing the violin, there wasn’t a lot of people that looked like us, you know what I’m saying? And, you know, we

grow — we were very fortunate to grow up in a really great foreign art school, and that’s why we wanted to put out this foundation, shout out to

the wives running the foundation.

And the foundation is really about filling the gaps, because in our lives maybe growing up, we had a lot of individuals who are very influential in

our lives that really filled that gap, whether it’s (INAUDIBLE) flight to a camp, music camp or, you know, paying for an instrument. So, we wanted to,

you know, fill in those gaps and we wanted to really help kids that looked like us, expose them to this new art — this art form. You know what I

mean?

So, that’s one of the things that — that’s why this foundation, we came up with this foundation, it’s really like a year and a half, two years, of us

doing this foundation and really — you know, the goal is really — just to really spread our net as much as possible and to really get kids really

exposed to art and really art in itself. You know what I mean? Not just classical music, just art in general, you know.

GOLODRYGA: And I know your inspiration and the inspiration for Black Violin with Stuff Smith. Kev, can you tell us — I know the pandemic has

sort of curtail any live performances and impacted musicians throughout the world, but can you give us the sense that you get from especially young

children and audiences when they come and see you perform, the reaction that you see from them and does that continue to inspire you?

MARCUS: Oh, definitely. I mean, most of the time, the people are — and when we come on stage, they’re sort of, you know, maybe puzzled, you know.

They don’t quite understand what we’re doing at the beginning. But by the end, you know, the messaging and the music is such that it’s very inclusive

and it’s something that it just feels good, you know, it’s just one of those concerts where just when you leave, you’re like, oh, like, you know,

you felt like you experienced something.

So, you know, we want to make an experience. Obviously, we want it to be musical. We want to have, you know, a five-year-old black kid and then a

70-year-old white lady sitting next to each other. And then after the concert, they have a conversation about what just happened, you know? So,

we want to bridge the gap by being able to make music that everybody is into and then also keep a message of unity and hope and love throughout the

entire thing.

GOLODRYGA: Well, listen, our audiences have also been deprived of hearing music and performances as well. So, I know you are prepared to perform us

off the show today. We’ve been looking forward to hearing this, “Impossible is Possible.” Can you please go ahead? And thank you so much for joining

us.

BAPTISTE: Impossible is possible. There’s a moment when you realize, all the things they said were lies. You’ve got to open up your eyes, because we

were made to fly. We can do anything. Come on. We shine like the sun, the moon the stars. We can go anywhere. They’ll see us matter where we are.

Because we’ve got the fire.

GOLODRYGA: Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.