Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR (voice-over): As Afghanistan verges on a humanitarian catastrophe, Zalmay Khalilzad, the former U.S. envoy who struck America’s

deal with the Taliban, joins me.

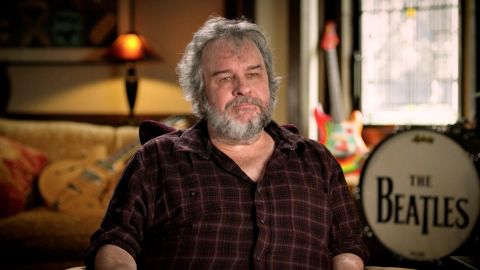

Then, “Get Back” director Peter Jackson shows us The Beatles as we have never seen them before.

And:

TOM MORELLO, MUSICIAN: The world is not going to change itself. That is up to you, like literally you.

AMANPOUR: Tom Morello from Rage Against the Machine talks to Hari Sreenivasan about social justice and making music through voice memos.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Afghanistan is bracing for winter amid a crisis of hunger and deep, deep poverty. Three months since the chaotic withdrawal U.S. and allied forces,

a U.N. envoy is warning that ISIS has now entered almost every one of the country’s provinces and the Taliban continues its relentless crackdown on

women.

So how did it get this way? And was there any alternative to the U.S. withdrawal?

Joining me now is Zalmay Khalilzad. He advised President George W. Bush when the U.S. invaded Afghanistan after 9/11. And he also negotiated the

U.S. withdrawal some 20 years later with the Taliban under President Donald Trump.

Zalmay Khalilzad, welcome from Washington, D.C.

Let me start by just putting what we have just said to you, because you have got the withdrawal, you have the abandonment of many Afghans who

supported the American war effort. You have the crackdown on women, and you have this looming famine.

Was there any — did you expect it to get this bad in the intervening a couple of months since the withdrawal?

ZALMAY KHALILZAD, FORMER U.S. SPECIAL ENVOY FOR AFGHANISTAN: Well, the situation is not good. The situation was not good before either. There was

a war going on that had gone on for a very long time. People were tired of war.

And now the situation is one of what to do on humanitarian front, as well as what to do to address the human rights concerns. And United States and

the international community needs to do its part, using diplomacy using what the Talibs want as leverage to address these issues.

But war was not the solution either. It had gone on for too long.

AMANPOUR: Well, we will talk about that in a minute.

But, right now, it is much, much worse in a humanitarian way than it was before the withdrawal. The Afghan economy is expected to contract by 30

percent this year. More than 95 percent of the population could fall into poverty and famine, many of them in the coming months. That’s according to

the U.N.

So should the United States lift the financial sanctions? Should it recognize the Taliban government in order to help the people with financial

aid and food and the like? Or should the World Bank, the IMF resume lending to the country?

KHALILZAD: I think the people of Afghanistan should not suffer as a result of disagreements that exist between the international community, including

the United States, and the Taliban.

What I have been advocating is to provide substantial humanitarian assistance, and to do that as soon as possible. But, in addition, the

Taliban have a list of demands from the international community. They want to be lifted — the sanctions to be lifted on them, including travel and

the lists that they are on. They want normal relations with the international community.

And they want to get assistance and recognition. And the international community has its own list of concerns, including humanitarian access,

including people having the right to travel, respect for the rights of all Africans, including women, and on terrorism front.

So, the two need to continue to negotiate, that is, the international community, the United States, and the Talibs, to fulfill the parts of the

Doha agreement that have not been fulfilled, what we, in other words, would be willing to do an exchange for what the Talibs do.

It has to be negotiated. And it has to be in writing. It has to be a step for a step by each side.

AMANPOUR: Yes, OK.

I guess you’re saying all that because, clearly, there were a lot of holes in the deal that was negotiated with you in the lead position. So I just

want to ask you personally, as you know, I have watched you battle diplomatically from the very beginning after 9/11 to get rid of the

Taliban, to bring a modicum of democracy and freedom and human rights to that country, to get rid of Talibanism.

And then, 20 years later, you go, as Trump’s terminator, to so-called negotiations in Doha, which brings them back full circle into power. Given

your career, given everything you have done, as an Afghan American, how do you feel about that?

KHALILZAD: Well, the question is, realistically, what were the alternatives?

And the alternative was the continuation of a war that we were losing. I mean, every year for the previous seven years, the Talibs were winning, and

there was no support for continuing that war effort in the United States.

And, second, that there was no desire to escalate, so the decision was made it’s better to negotiate. I wish the situation had been different. But we

can’t wish things. We have to deal with realities that we have. And the president of the United States, a Democrat and a Republican, actually,

three presidents, starting with Obama, wanted to end the war.

The world that change. China become a bigger problem to focus on. Terrorism was not the same as it was before. And the Afghan situation was not moving

in the right direction. Given those circumstances, the agreement was the best option possible that could be arrived at.

That the Afghan government and the Talibs didn’t take advantage of the opportunity provided by the United States, that is, to start inter-Afghan

negotiations that had not taken place for the previous decades, that is a historic a mistake that they made.

But the business of Afghanistan and our concerns are not over. Now, using diplomacy, assistance, release of funds, political normalization, those are

the leverages that are appropriate for the current circumstances.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KHALILZAD: I wish things had been different, but they weren’t. And we had to deal with the situation that we have.

AMANPOUR: OK, so let me tell — OK. OK.

But you knew everything about Afghanistan. You were probably one of the most knowledgeable of the country. And, of course, nothing was perfect. And

many of those things you say are true, that the country was fed up with war, and the three presidents you mentioned wanted to withdraw.

However, there are still many people who criticize your negotiating tactics, and suggest that you gave away too much to the Taliban without any

— without them fulfilling any of the conditions or promises. Even a Trump administration official, Lisa Curtis, who worked with you on this issue: “I

believe Ambassador Khalilzad was too willing to make concessions to the Taliban and to throw the Afghan government under the bus.”

One of your former allies in Afghanistan, a former vice president, said you were the architect of a great deception.

So react to that. And also I want to ask you myself, did you have — did you really think that the Taliban was interested in anything else than a

military victory, which they actually achieved?

KHALILZAD: Well, I mean, there are people in the United States who were supportive of continuing war in Afghanistan. And I respect that. But they

were not the people in decision-making.

President Trump and President Biden are elected leaders of the United States. They are the one who decided and they are the one who decided on

the terms of the agreement. So, I think commentary is one thing, but the reality was that, given the circumstances and the trends, the agreement was

the best that could be achieved, and it gave the United States what it wanted, a safe withdrawal of its troops.

Not a single American was killed since — by the Talibs since the agreement was signed. The Talibs agreed that we could come to the defense of the

Afghan forces if they attacked them after the agreement. The Talibs agreed with both sides they will set together and negotiate.

That was introduced, agreed to in the agreement. The fact that the government wanted the war to continue, and some in the United States for

reasons of their own wanted the war to go on, ending a war is not easy. There is a lot of interests involved in continuing the war. That is their

point of view.

But the United States government, the president, several presidents decided this war was not going well, it was better for the U.S. to cut its losses,

focus on the problems of the current period, and give the Afghans the chance to negotiate with each other.

And there was a lot of pessimism whether the Afghans would agree to with each other on a political settlement, and the pessimists turned out to be

right. But we have to continue the effort.

AMANPOUR: Right.

KHALILZAD: Why did — the Afghan forces did not fight? Why did President Ghani run away? These are questions that have to be asked. Lessons have to

be learned.

But there was no realistic option for continuing the war.

AMANPOUR: Well, so let me ask you.

Many Afghan — many of the military forces that the United States backed are very upset, and they believe they’re being slandered by all the

Americans who say they refused to fight, which we know they did fight, and they lost tens of thousands of their own people over the years in a joint

effort.

Many say it was when the United States made it clear that they would no longer support them that they had nowhere to turn. And you know

Afghanistan, and you know how people roll over allegiances, depending on where they think — and who they think is going to be in power.

But you also, and you admitted yourself, asked the government — you suggested your old friend Ashraf Ghani, the president, that he resign, as

the Taliban demand demanded at Doha. Tell me why you thought that was a good idea at the time as part of the negotiations.

KHALILZAD: Sure.

First, I do agree that individual Afghan soldiers did fight bravely. But when push came to shove, and they, to our surprise, to everyone’s surprise,

the armed forces collapsed. There are lessons to be learned from. Did they collapse because they were too dependent on the United States

psychologically and operationally? That raises questions about how we help build security forces for other countries, although the fact is that, in

the agreement, we retained the right to come to their — to the defense of the Afghan forces when they were attacked.

And we did that. That was an extraordinary concession from the Talibs, that they wouldn’t attack us, but we could attack them.

Regarding the — a political settlement, I have to say that, given the balance of power, when the negotiating teams from the two sides were not

making progress, the United States did propose a possible compromise, that the government will be made up of elements from both sides, perhaps as

50/50 percent, and that the head of the government would be someone acceptable to both sides.

Now, wouldn’t that have been better, given what happened? It was a terrible miscalculation on the part of the President Ghani and his team that they

thought that was unacceptable. And look what happened, given realities on the ground. Wouldn’t Afghanistan have been better off with a mutually

accepted head of state with power-sharing and a legitimate government not subject to the kind of steps that the current government is subjected to?

AMANPOUR: Did you feel your hands were tied, given that President Trump made it very clear that there was no more leverage because they were —

they had a set date to withdraw?

KHALILZAD: Well, I had to deal with the situation that I had, not the situation I wished I had.

And the president, President — I negotiated a condition-based agreement. And the four conditions were U.S. withdrawal, but in exchange for Talib

commitment and the Afghan government commitment on terrorism, negotiations among Afghans and a comprehensive cease-fire, that, ultimately, President

Trump and President Biden both decided to follow a calendar-based withdrawal, not a condition-based withdrawal.

Those were decisions way above my pay grade. But I think, given those realities, the war not going well, the desire to adapt to the new

international environment, the new terror environment…

AMANPOUR: OK.

KHALILZAD: … Afghanistan’s leaders not willing to negotiate with each other, all caused the president of the United States to say, we should just

get out there on a calendar, on a timetable.

AMANPOUR: OK. And the result is a disaster. I mean, let’s just not beat around the bush.

The result is a disaster, when more than half the country about to be — have famine conditions and poverty. They need help. They’re not getting it.

Women are being completely abused and their rights taken away by the Taliban.

This is what Fawzia Koofi, who I know you know very well — she was the Afghan government representative at the talks — this is what she told me

more than a month after the collapse of Kabul and the withdrawal of U.S. forces about the women.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

FAWZIA KOOFI, FORMER AFGHAN LAWMAKER: The expectation of people in Afghanistan, especially the woman of Afghanistan, is that the world

continue to use their leverage for the rights of women, because, after 20 years, Christiane, for us to talk about the rights to education, it’s

heartbreaking.

Honestly, as a woman, it’s heartbreaking for us to see that we’re still struggling for our right to go to school.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

KHALILZAD: Well…

AMANPOUR: So, Zalmay Khalilzad, it is heartbreaking because of the great successes that came after the U.S. invasion in 2001. Women’s rights and

children’s rights were a huge success.

So I guess I want to ask you, did you expect the Taliban to do this?

(CROSSTALK)

KHALILZAD: It was a great success for part of Afghanistan’s society.

AMANPOUR: Right.

KHALILZAD: And those who were benefiting from the U.S. presence now are — some of them are upset because the U.S. has withdrawn.

But I believe the women’s rights issue is an important issue. It will — should be a central factor in affecting U.S. and international policy

towards Afghanistan. But we shouldn’t be driven by revenge or by the desire of part of the Afghan society who are nostalgic about the days that they

were dominant, but they couldn’t really conduct a policy that was successful.

And they couldn’t also be realistic enough to make a peace agreement. The time has come for Afghans to accept each other. They are different in terms

of their values. They have to come to an agreement on a formula for Afghanistan to work and for the international community to assist in that

regard.

AMANPOUR: OK.

KHALILZAD: But continuing the war, in which thousands of Afghans lost their lives, and parts of Afghanistan was devastated…

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Yes, yes, yes. You have said this before. You have said this before. I have…

KHALILZAD: … and the American decision that that was not sustainable…

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KHALILZAD: … that those were also not the realities that could be sustained.

AMANPOUR: OK, Zalmay Khalilzad, I hear the hand — I hear the sound of water as you on behalf of the American government wash your hands of

everything there, including the women.

So I’m going to ask you a last question. Do you share the outrage of the American military service members, the American military members…

(CROSSTALK)

KHALILZAD: We’re not going to wash our hands off, but the mission of the U.S. military was not a humanitarian mission, except in exceptional

circumstances.

AMANPOUR: Mr. Khalilzad — right.

KHALILZAD: The mission of the U.S. military was to go to after the Taliban because of 9/11. And the Taliban have been…

AMANPOUR: OK. I understand.

KHALILZAD: Have paid a high price for that mistake they made. They say they will not make that mistake again.

But as far as the future of Afghanistan is concerned, the U.S. uses — will have to use…

AMANPOUR: But they are. They make the mistake again now.

(CROSSTALK)

KHALILZAD: … instruments.

AMANPOUR: I just need to ask you one more question, one more question.

What about the American servicemen who are absolutely crushed that the people they gave a sacred promise to who helped the war effort have been

abandoned? Do you share that sense of a betrayal?

KHALILZAD: No, none at all.

We — the — these people fought for themselves, not for the United States. Afghans fought for Afghanistan. The self-flagellation that some suffer from

is unwarranted.

Afghans fought for themselves, not for the United States. The U.S. fought for itself and helped Afghanistan. But it didn’t work. It worked in some

ways. The Talibs were punished. Hopefully, they will be deterred from doing what they did the last time.

AMANPOUR: All right.

KHALILZAD: And Afghanistan was transformed.

But the time has come for Afghans to come together, agree on a political road map for themselves, and the international community should assist.

AMANPOUR: All right. All right. Well, let’s see if that all comes true.

Zalmay Khalilzad, thank you so much for joining us.

KHALILZAD: It’s great to be with you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: And, next, we go back 50 years to an unseen treasure trove of music and film of The Beatles.

You think all there is to know about the Fab Four. Think again. None other than the Oscar-winning director Peter Jackson has worked his “Lord of the

Rings” magic on this ancient archive to give us a whole new view of some of the last Beatles recording sessions and a whole new take on whether the

famous rooftop concert was in fact a break up offering to their fans.

Here’s a clip from Jackson’s film “Get Back.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PAUL MCCARTNEY, MUSICIAN: We’re talking about 14 songs we hope to get.

GEORGE HARRISON, MUSICIAN: How many have we already recorded good enough?

JOHN LENNON, MUSICIAN: None.

MCCARTNEY: And none of us has had the idea of what the show is going to be.

LENNON: I would dig to play on the stage. Nobody else wants to do a show.

MCCARTNEY: I think we have got a bit shy.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, all of this drops as a three-part series on Disney+ later this week over the Thanksgiving break.

And I have been speaking to Peter Jackson about the amazing new light that he’s shedding on John, Paul, George, and Ringo.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Peter Jackson, welcome to the program.

PETER JACKSON, FILMMAKER: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So what is your earliest memory of The Beatles? I mean, were you a fan from being a child, or what?

JACKSON: Well, I was born in 1961. So, theoretically, I was alive when all their albums were coming out.

But I had a mother and father who were not Beatle-orientated. I mean, they — like my — at home, we had the soundtrack album of “South Pacific” and

those were sort of things, not a single Beatles record.

So I have no memory particularly of The Beatles during the ’60s, apart from the fact that I must have liked them. I must have heard them on the radio.

I must have seen them on TV, because as soon as I could save up enough pocket money, which took me until I was about 12 — I went out about 12.

I went into the city, went to the record store, and I bought my very first Beatle album. And they’d already broken up at this stage, which was about

1972 or ’73. But I spent my first bit of pocket money buying my first ever Beatles album.

So I must have liked them. Yes. So, yes.

AMANPOUR: I guess this was then meant to be. I mean, Peter Jackson was meant to put this incredible series together.

Are you surprised that one of the most mega-groups of all humankind of all time actually had 50-plus hours of unseen film footage that’s been — or,

no, more — that hasn’t been seen for so many decades?

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MCCARTNEY: The best bit of us always has been and always will be is when we’re backs against the wall.

LENNON: All we have got is us, don’t you think?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

JACKSON: It completely blows my mind.

And I’m not describing my — the film that I have made and anything else, just the fact that this stuff, after 50 years — over 50 years, all the

documentaries, everything, we — you have got to think you have seen everything there is to do with The Beatles.

So, the documentaries you see tend to recycle the same footage, “Ed Sullivan,” press conferences, so that you just sort of think, OK, well, we

have sort of seen it all. And now we’re just looking at interviews and various things.

Suddenly, out of nowhere seemingly out of nowhere, there’s — and it’s not just that there’s 60 hours of new Beatles footage. It’s actually the best

Beatles footage that has ever been seen.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg shot it in 1969. And it was used for his movie “Let It Be,” which was about 80′ minutes long. So we’re talking about the outtakes

from “Let It Be,” which is essentially 60 hours, that The Beatles, because of the whole stigma of the breakup when “Let It Be” was released, they

actually — I mean, it’s The Beatles themselves that have ordered this to be locked in a vault and never be seen.

It’s not just that it was lost and forgotten about. They have never wanted anyone to see it.

AMANPOUR: OK, so that’s — that’s incredible. I actually didn’t know that nugget. So that’s really interesting.

JACKSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So I guess the next question is — well, clearly, you obviously got the key to the vault.

JACKSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: But did you negotiate or talk with the two remaining Beatles, the two living Beatles? Were they part of the creative process at all for

you?

JACKSON: I didn’t. I didn’t talk to them when sort of the actual thing was being hatched. That was done with the chiefs of the company, Jeff Jones and

Jonathan Clyde, who worked for Apple Corps, who are the — is The Beatles’ company.

So, discussing the idea of the film and me jumping on board was all done there. I got the idea that they weren’t going to give me access to Paul and

Ringo until it was all kind of — until it was under way. And then, certainly, once it was happening, and I was on board, everything had been

sorted out, then Paul and Ringo have been available to me ever since, incredibly supportive, and has Sean Lennon and Olivia Harrison and Dhani

Harrison.

The entire group have been incredibly supportive, and in a way not just supportive. They have done — they have given me the greatest gift that I

could ever have, as they have they have left me alone.

(LAUGHTER)

JACKSON: They have always been there if I want to ask them something, but they never — they have never — they have always just had — they have

always let me make the film that I want to make, which I really am very, very grateful for.

AMANPOUR: Well, really interestingly, Paul McCartney has been interviewed, obviously, about this and on “Fresh Air” with Terry Gross.

He said that what you provided was this incredible sort of like — almost like a family scrapbook. He — even his memories had dulled over the years

and maybe been overtaken by the chat that the world was having about what this original film was.

Let me just play what Paul McCartney said.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP)

MCCARTNEY: Overall, I think it proves that there was a great loving spirit in The Beatles that entered into the music and everything we did.

And that, for me, was more than a relief to see it. It was great. It was very emotional and very lovely to be able to see John and George again and

just remember how sweet it was to work with them and to make this music.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I think that’s really nice, because, certainly, from what we hear, Peter Jackson, is that the original film “Let It Be” was almost

considered to be a breakup film. Did you find that when you looked at all the outtakes?

JACKSON: Well, just to talk about “Let It Be” for a second, because, I mean, Michael Lindsay-Hogg shot all this footage of — the footage that my

film is being from. And he shot it in 1969. And he made his film, “Let It Be.”

And his movie is absolutely — it’s not a breakup film. And it’s — and his movie had the bad luck of being released after The Beatles had broken up,

because, of course, once he had shot all the footage — I mean, he shot the 60 hours of footage that I have in January ’69.

That wasn’t the movie finished. He had to go away for a year and all the editing. I mean, it’s taken us four years to edit it, but Michael managed

to cut his film in just over a year. And so he was working on that. And The Beatles, in the meantime, before his film came out, they broke up.

So, his movie, obviously, he shot the footage as this incredible fly-on- the-wall look at The Beatles. Then you go — in January ’69, you go to May 1970. “Let It Be,” his movie, comes out. The Beatles have just broken up.

The headlines are saying they have broken up.

People go to this fly-on-the-wall film. And people would assume that this movie was shot a month ago, two months ago. This must be The Beatles in the

process of breaking up. They imposed the newspaper headlines onto Michael’s film, which was actually very unfair for the movie.

But, nonetheless, that stigma has — it has survived for 50 years. So much survived, that it actually become a fact. It’s become the absolute — but

how can it be a breakup film when it was shot for 15 months earlier? It just can’t be. It’s impossible.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

And you were saying, I wanted to know what was going on. Well, clearly, what was going on was unbelievable songwriting and music-making.

JACKSON: Yes. Amazing.

AMANPOUR: And in those 22 days, they created 14 songs that became and have remained iconic Beatles songs.

How surprised were you by the work ethic or the method of their — of how they worked and how they produced together?

JACKSON: So, you’re quite right. In that time, they — they write and record the 14 songs on “Let It Be.” They — also the “Abbey Road” album,

which is about — this is going to come out in about six months from this period — 17 songs on “Abbey Road,” 12 of those songs are done during this

period as well.

Probably about 10 or 12 songs that appear on their solo albums are actually done. You have got — George Harrison released a solo album called “All

Things Must Past.” It’s a song. We have got the we have got The Beatles performing “All Things Must Pass.”

“Gimme Some Truth” is a very famous song that John had on a solo album. It’s on the “Imagine” album. The Beatles are performing “Gimme Some Truth.”

All the solo songs that I have always thought of them as being solo songs, you have actually got the group performing them.

And, in addition, during this period, they perform about 220 old rock ‘n’ roll songs at the same time. So, point of fact, yes, they are incredibly —

this is a very — and it’s actually — in this 22 days, the last 12 days, they work every day. They don’t have the weekend off. It’s like 12 days in

a row.

Their work ethic — the actual worker ethic is extraordinary, focused, professional, but also full of humor as well.

AMANPOUR: And really full of affection for each other.

JACKSON: Oh, yes.

(CROSSTALK)

JACKSON: Yes. Yes. Yes.

AMANPOUR: And it was so interesting to see Yoko there as well. And this was in the early days of her relationship with John, and to see Linda, who

at the time was Linda Eastman, taking the pictures there.

What can you tell us about that dynamic, what you gleaned from the 60 hours of video? And, of course, Paul has said recently that he just wants to

clear up once and for all with this film and with the book that he’s writing that he didn’t break The Beatles up.

JACKSON: Look, Yoko sits with John in the studio, which, as I was a Beatle fan, younger, you would see photographs of John and Yoko in the studio, and

you would think, oh, that’s a bit weird.

But when you see the footage, and you just watch them work, she’s very respectful. She never interferes. She never has an opinion. She doesn’t

say, oh, I think solo should be faster or things. She writes — she reads newspapers.

She’s — and she is only there because Yoko and John are completely in love. So, what is wrong with that?

She’s not there to make trouble. They’re in love and they want to stay — you know, John doesn’t want to leave the house and leave her alone and be

away from her for eight long hours, and why should he? So, it’s sort of — it’s strangely normal. It’s always felt weird when I’ve looked at photos.

But when you see them sitting there and they’re all working, it’s amazing. OK. It’s fine. It’s fine.

AMANPOUR: And I mean, it’s extraordinary, I hadn’t known that in the middle of it — or the beginning of it, George Harrison just announced very

matter of factually, I quit, and he left.

JACKSON: Yes, yes, yes. Oh, no. he does. You see, the interesting thing, Christiane, is that — you know, you had talked about how much love and

affection they have for each other. And in way, where that comes through strongest is when things go wrong. So, there are moments like George walks

out and you see the affect that that it has John and Paul and Ringo.

You know, first of all, they’re Northern sort of macho boys from the North of England. So, it’s all macho, you know, Eric Clapton. And — but that

drains. That macho, they can’t actually sustain that and they sink into a depression. And, you know, because they are devastated by George leaving,

even though they’re trying to hide it. You can see how they are.

And, you know, the overall plan that they’re trying to do derails. And so, in a way, we see more of The Beatles personality, more of their friendship,

their deep friendship and their love because they are all having to deal with this kind of crisis. I mean, if at all was playing soundly, you sort

of wouldn’t (INAUDIBLE) that you’d actually get much of a sense of who they were. But the fact that they’re having to deal with enormous problems sort

of really shows you who they are. And ultimately, they get through because of a long hard friendship.

I mean, when The Beatles — when these kids in our Liverpool got together as a group, George Harrison was 13 years old, John Lennon was 16. I mean,

these guys are all childhood friends. You know, by the time we see them, there is a deep brotherly trust and almost a psychic bond between them.

AMANPOUR: And then, there was the magic of the actual performance. Because let’s not forget, this was meant to culminate in a performance and they

hadn’t performed, if I’m not mistaken, for three years previously.

JACKSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And it says, they just decided to walk upstairs and go and do it on the roof, which clearly surprised everybody in the neighborhood. Talk me

through how that impacted you when you saw that and all the different cameras that the original film had employed to capture every angle.

JACKSON: Well, the rooftop concert, which is they go up and perform nine times. They perform five songs nine times, because they’re not only doing

actual concert on the roof, they’re — it’s a recording session. They have all the amps and the mics — you know, go down five stories to the

recording studio in the basement, you know, there’s cables down the staircase. So, they’re actually there to record for an album. It’s not sort

of technically just a bit of fun on the roof. So, they play a few songs multiple times to get them right.

And anyway, I’ve seen bits of the rooftop concern. I mean, I’m sure that we all have in various documentaries of it, you know, one or two songs. And

the 16mm film has all been grainy and a bit dull. And to be honest, I’ve never really liked (INAUDIBLE). So, I’d prefer to watch the stadium or, you

know, watch The Beatles play. So, I’ve never really been a huge fan. It’s always failed a bit.

And I’ve also projected all the break-up stuff the same everybody else onto the footage. So — but when I looked at the rushes and I thought, OK, I

just want to look at the rooftop rushes because I know that they did — it’s 45 minutes long, the full thing and they had 10 cameras filming. So, I

just sat there and I looked at all these 10. And we had it so that all 10 was sort of going at the same time. I just sort of watched it over.

And I just thought, you know, I — and I just though, this is the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in my life. I mean, this is the most

extraordinary footage shot of The Beatles in performance. And in a way, it has to be seen as fully to appreciate that because what you get apart from,

you know, the angles and the shots, you get the sense of these guys up on the roof. They haven’t played together for — as you say, for three years.

They want to be — they want go back, get back as the name of the film. They want to get back. They don’t want to be Sergeant Pepper anymore. They

don’t want to do the show stadium laptops. They’re going to be — they want to go back the (INAUDIBLE).

They want to go back to their teenage and just play rock ‘n’ roll, four guys. And they haven’t actually done that for a long time. And they were

nervous. They don’t know whether they can recapture that. And the first song, you know, OK, a little bit rough. The second one gets better. And by

the third song, they are cooking.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

JACKSON: So, you actually see it around. You really are emotionally on their side. And by the fourth song, they are having a blast. So, in a weird

way, they’re playing. They’re surprising themselves at how great they are. Because they’ve actually forgotten how great they are. You sort of see —

you see on their faces. And they’re take it so intimate. God, they’re tight. And such a great performance. So, you know, seeing the full thing

has become my all-time favorite Beatles performance. And I hope other people will feel the same way.

AMANPOUR: It’s amazing. Did they approach you because of this incredible film that you did about World War I, “They Shall Not Grow Old,” a way you

took, you know, original pictures and restored them and added color. And I mean, we know how great that film was. Is that what led them to you as you

also had to sort of restore or adjust, I think, somehow some of the film, right, because it was not —

JACKSON: We certainly did — so the “They Shall Not Grow Old” helped us, ultimately with the restoration. No, no. This is the ultimate being in the

right place at the right time story. I was — you know, I work in New Zealand at the time. This is four years ago and maybe five years ago. I was

traveling to London to do “They Shall Not Grow Old,” going to the imperial war machine, film vaults and look at them. So, to be honest, making these

sorts of trips.

And one of these trips (INAUDIBLE) must have heard. Obviously, I don’t know how they did it. They must have read an interview with me because I hadn’t

met any of these guys before. Because I had been — at the time, I was interested in VR, AR and all the, you know, putting sort of glasses on and

I still am, but — so, I must have talked about that in an interview that they’ve seen. Because I got this note while I was in London to ask if I

wouldn’t mind dropping by Apple Chords (ph) and have a chat with Jeff (INAUDIBLE) and Clyde about VR and AR.

And I go there. They tell me that they’re thinking about a Beatles exhibition of some sort, a live exhibition, and they are thinking about the

technology — you know, could they have — not necessarily can you do it, but it was just like, can you — you know, we’re hear you’re interested.

Could you explain to us how this works?

And so, I sort of — we talked about that for a bit. And, you know, as a Beatles fan, over the years, I’d always had this thought in my head,

(INAUDIBLE), Michael shot this footage. His movies — I know he shot a lot more than that, I don’t know how much. I wonder if the film survives. I

couldn’t really get the answer for any books, but I’ve always wondered, is there other B outtakes that no one’s ever seen?

So, the right moment in the meeting and trying not to sound like a fan trying to (INAUDIBLE). I say to them, you know, let it be. There’s

obviously more footage. Did any of those outtakes survive? Because, you know, because that might be interesting. We could use some of that for AR,

VR thing, which was not really the reason. I just wanted to find out.

And they said, oh, yes. Yes, yes, yes. No, there’s 60 hours. 130 hours of year. All that is saved. And they said, it’s strange that you mentioned it

because, you know, we’re actually — we’ve been having eternal conversations that maybe we should look at it and there might be something

we could do with it. Maybe as a documentary we could make with the outtakes, but we’re not sure. You know, we haven’t seen it. We have — and

I said, oh, you gotten anybody, a filmmaker involved? No, no, no. We haven’t got that they.

And they only said, oh, actually, let’s forget the AR, VR thing. If you want someone, I’m pleased. Think of me. And so, they almost immediately

said yes. So, I arrived at the meeting to talk about AR, VR. I walked up as a director of get — right place at the right time.

AMANPOUR: Indeed. And a Thanksgiving treat for everybody when it drops on Disney Plus. Thank you so much Peter Jackson.

JACKSON: Thank you very much.

AMANPOUR: We look forward to seeing it.

JACKSON: Thank you so much.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: A treat indeed. And our next guest is also a musical star but a very different one. Tom Morella is best known as the guitarist of the rock

band Rage Against the Machine. But you’ll find his latest work in print as he’s writing a series of essays on his music and on social justice for the

“New York Times” or while preparing to release his new album next month. As he discusses in conversation with Hari Sreenivasan now.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, thanks. Tom Morello, thanks for joining us.

How did you pull off a collab album in the middle of a pandemic?

TOM MORELLO, GRAMMY AWARD-WINNING MUSICIAN, NEW YORK TIMES COLUMNIST: It was my only choice. How it began was, I have a studio at my home but I

don’t know how to work it. Normally, there’s an engineer who is moving a knob. The only one they allow me to touch is the volume know, and that

rarely.

So, during the — you know, during the beginning of lockdown, I was staring at a future without making music. An inspiration struck at a very — from

an unlikely source. I read an interview where Kanye West was bragging about recording the vocals for a couple of hit albums into the voice memo of his

cell phone. And I thought, perhaps I can record my guitar into the voice memo of my cellphone, and I did and it sounded fantastic.

So, I began sending out these voice memos of guitar rips and guitar lyrics to various engineers, producers and artists around the world and began

creating this kind of rock N roll pen pal community that, while I was in complete isolation here, was able to create a lot of music globally.

SREENIVASAN: So, you basically tapped into a bunch of frustrated musicians all figuring out like, wait, this is part of who I am, and that has been

pent up for these days and they’re like, play some music, I can do this.

MORELLO: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, this record, “The Atlas Underground Fire,” it’s just a record, “The Atlas Underground Flood” come

out on December 3rd where as much life raft and antidepressant as they were sort of creative endeavors. It was a way to — you know, during the really

sort of anxiety-filled time to remind myself that I am a guitarist, I’m an artist, I’m a songwriter and allowing — and also, when — at that time

when every day felt like it was kind of exactly the same, to have the unknown in these collaborations. You send something out. It comes back

transformed. And that really felt like a life raft during a pretty troubled time.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: When I look at “Atlas Underground Flood,” I mean, what do Ben Harper and Manchester Orchestra and Break Code have in common besides you?

MORELLO: Yes. What they have is they’ve picked up a phone when I called them that particular day. It’s just — it’s like-minded musicians of

different genres coming together to create something that we both love. Now, part of the mission of this, and I use the word literally like a — as

a missionary work, you know, I firmly believe the electric guitar is the greatest instrument ever invented by humankind from its nuance. Spreads

nuance to its power. But I also believe it’s an instrument that has a future and not just a past.

And so, by integrating my vision of electric guitar into whether it’s a song with country artist, Chris Stapleton, or EDM artist Break Code or

alternative artist, Grandson, or Palestinian DJ, Sama’ Abdulhadi, finding a — like having my curation and the voice of my guitar to be the common

thread through these different genres to find a way — a forward — facing forward way for rock N roll and for the electric guitar.

SREENIVASAN: So, what is it about the guitar? I mean, you have said before that it chose you. What does that mean?

MORELLO: Yes, yes, yes. I had a myriad of interests. I started playing the guitar late. I didn’t start playing until I was 17 years old. So, it was

really two years in. I was a freshman at Harvard University when I was, you know, toiling away, playing some cover song in a basement rehearsal room

between the foosball table and washing machine when the skies parted. I stumbled upon sort of a moment sort of improvisational bliss.

And it was literally felt like a calling. The skies parted and I knew then that I would be a guitarist. I had to find a way to sort of them my

political science major, you know, to pass my courses while at the same time practicing four to eight hours a day, but that was my burden to bear.

SREENIVASAN: You know, there are times when you listen to some of your early work and it is powerful, it’s rocking. I mean, it’s just super energy

filled. And then, there’s times where I listen to some tracks and you’re like, this guy is at some sort of a coffee house doing an open mic night.

And you wrote in one of your columns, one of the things that kind of was a distinguishing, I just want to pull up this quote. These songs enabled me

perhaps for the first time to peek into my own soul when I found that it might be haunted. On the surface, I was affable, reliable, cheery rocker.

When I picked up acoustic guitar, I tapped into a deep vein of the union (ph) shadow, the dark repressed aspects of my personality, they’ve cut much

closer to Edgar Allen Poe than Edward Van Halen.

So, are you trying to juggle these different parts of you?

MORELLO: Yes. Well, I’ve — I mean, I’ve been drawn to heavy music. For me, first, it was heavy metal then it was punk rock and then hip-hop. But

it wasn’t until my 30s where I tapped into like folk music and whether it was the early Dylan records or Woody Guthrie or Springsteen Nebraska and

Johnny Cash and realize that, you know, three acoustic guitar chords and the truth can be just as heavy as anything in the Metallica catalog.

And that was where I began sort of finding a different way to express myself, which has always been sort of cranked to 11, through a marshal

stack and here, I’m going to attempt to reinvent the electric guitar. I realized that I had a more to say and I had a lot more to say. And it

really began with — there’s — it was on that same “New York Times” article where I was at a teen homeless shelter in Hollywood and it was like

a Thanksgiving talent show kind of thing and I was there.

And some young man got up there. Again, a lot of problems in his life. His guitar was out of tune, his voice shook but he played as if every person’s

soul in the room was at stake. And I was like, hold on. Like there’s — like do I have anything like that to say? And I found that I did.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Let’s go back a little bit. You grew up in the Midwest. You had a father who was from Kenya. A mother who was Irish American. And the

identity struggles is what intrigues me, is did you or were you identified as a black man, an African American young man and did that change over

time?

MORELLO: Yes. Yes, definitely. I literally integrated the Town of Libertyville, Illinois in 1965, according to the real estate agent that

helped my mom and I find our first apartment. And, you know, it was quite a journey. Yes. I was — in the town I grew up in, I was the — you know, for

years, I was the only black person in town and my mom who had an excellent teaching credentials was looking for a job teaching public high school and

couldn’t find a job in some of the surrounding communities because we were an interracial family. My dad did not live with us. But I was the

interracial part. I was a one-year-old half African kid.

And so, Libertyville offered us the — the school offered opportunity to teach there, provided that we could find a place to live. So, the real

estate agent went door to door in the apartment complex across the way and explained to the other people living there, this is no normal American

negro child, this like like sort of an African princeling who is going to be living there, which was — which, you know, allowed us a toehold until I

was old enough to date their daughters. And then, that whole situation changed. But it was — you know, one morning when I was 13, I woke to find

a noose in my family’s garage. It wasn’t the only noose I saw, you know, growing up. The N word was a thing that was a constant. People touched my

hair, marveled at the color of my gums and palms and questioned openly if I was their intellectual equal throughout my growing up.

It was a bucolic community with grade schools and whatnot too, but I was black, super black. Then, years later, I played in rock bands that were

traditionally heard on radio stations that were traditionally reserved for music made by white artists and in magazines where — which normally

featured white artists. And, you know, my speech was not stereotypically urban and there’s a wide swath of my audience that to this day is unnerved

when I mention that when I self-identify as black in an interview.

They’re like, this is cognitive dissonance that kicks in. Like someone who makes music like that must look like me, mustn’t they? And it’s very

strange. Because my — while my skin color hasn’t changed through the years, I have changed color in the eyes of people that I encounter.

SREENIVASAN: You know, you’re successful by most measures now but come out of Harvard, moved to L.A. And I don’t have any YouTube proof of this, but I

heard you were literally taking the shirt of your back to make ends meet.

MORELLO: There was exotic dancing stints between Harvard University and — between graduating from Harvard and working as the scheduling secretary for

a United States senator. Yes, I did work as a stripper at national rep parties because the rent is not going to pay itself. Sorry.

SREENIVASAN: Is that in the Harvard alumni listing for you?

MORELLO: My resume has some rich eddies.

SREENIVASAN: You know, you have been talking about social justice issues for — as long as I can remember. I mean, I came into your music when I was

in college and Rage Against the Machine was all the rage. And, you know, at the time, you were singing about a different presidency. You were singing

about kind of a war that was raging for kind of a different reason. And I wonder, here in the past two years, so many of the lyrics that your band at

the time had written found a new residence. And are you sad that they’re still relevant?

MORELLO: First of all, all credit to Zack de la Rocha, the lyricist of Rage Against the Machine and Timon Brad (ph), my brothers in arms. But —

yes, I mean, I think that’s — it would with naive to assume that, you know, you make a few albums and be, you know, a socialist utopia erupts

around you. And the way I look at it is, is that, you know, each day and each work of kindness and resistance is another link in the chain to try to

fight for a more just and humane planet.

If there’s one threat that runs through 22 albums is that the world is not going to change itself. That is up to you, like literally you, whoever’s

watching or listening or whatever. And while that may sound daunting, there is great historical precedence for — on your side. And when the world has

changed and progressive radical or even revolutionary ways, there’s been changed by people with no more power, influence, money, creativity or

intelligence than anyone listening right now.

History is not something that happens, history is something that we make, and we are agents of history. And it’s just a matter of standing up in your

place, whether it’s your home, your school, or your place of work or your country to, you know, aim for, you know, the world you really want without

compromise or apology. That’s what I’ve tried to — you know, what I try to do when I’m trying to have my music be about.

SREENIVASAN: You are one of the people who doesn’t hesitate from the word class in conversation and lyrics. And I wonder in the last year or so, we

have seen more union struggles, for example. People — this sort of great resignation. People are also saying, maybe it’s a great reassessment that

people are not willing to work the kinds of jobs for the kinds of renumeration that they have today. And I know one of your recent songs

“Hold the Line” was explicitly about sort of union protests.

MORELLO: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: I mean, do you find the things have change? I mean, is it just a drop in the bucket? Where do you see in the larger arc?

MORELLO: Yes, yes. Well, I mean, this — what we were calling Striketober was like the most people on — the most individual unions and people on

strike or walkouts to create unions that we’ve seen in a very, very long time. And I think that like leaning into the five-letter dirty word class

is something that we have to do if we want to see any sort of real change.

I think there is so much power in the working class and in unions. I’m a proud member of Musicians Local 47, a proud card carrying — red card-

carrying member of the Industrial Workers of the World. The Morello’s were coal miners in Illinois. And just the idea that we should have agency in

deciding in the place we work what happens there is something that should not be a foreign notion. And the way you make that happen with the simply

word solidarity. That’s how it’s happened before.

And I’m hopeful that there is a significant resurgence, not just in union membership but in militant union action to continue to create the kind of

world that serves the people in it. Because the people who own and control the world do not deserve to. And clearly, their actions are not only

endangering environmentally civilization and life on earth but in a real paycheck to paycheck way, people who are trying to make better lives for

themselves and their family. And the only way to fight back against that is together.

SREENIVASAN: Right now, given the way the two-party system is structured in the United States, how do you think the labor movement or the working

class get a voice at the table?

MORELLO: There’s a couple of ways to look at. Do you — how do you find — get a seat at the table or do you overturn the table entirely? Like

everything — I think everything needs to be on the table now where we’re literally looking at sort of potential environmental — like a reorienting

of how people are going to live based on criminal capitalist endeavors. Like are we going to be OK as a species based on how we look at the — how

we weigh profit over the sustainability of humanity? I think those are things less — those are things that people have to look at.

Now, as I’ve said, like I am currently — I’m stuck being guitar player. I think there are other ways where I might sort of effect change in the

world, but I’m just going to keep making songs about it.

SREENIVASAN: Is the “New York Times” column kind of in the lineage? I mean, is this sort of — you’re trying to be a change agent or what are you

trying to do with it?

MORELLO: Yes. Well, it’s funny you mention it. Like these records in the “New York Times,” it’s one more way to stay sane during an insane time,

like sort of hang on — during an inhumane time to hang on to my humanity. I never set out to be a, you know, “New York Times” columnist and I had

great trepidation about it, you know, there’s sort of mixed feelings about the venue.

But it has been — you know, those articles have resonated in a way. And I hear from people every day sort of dwell outside of the normal circle of

people I hear from who, you know, find something in them that’s worthwhile.

And again, I will say this. This is something which I’ve also found in my music is when I was asked to do a column for — or when it was brought up

to — potentially doing a column for the “New York Times,” I thought, well, I’m going to be doing, you know, a lot of research on these particular

topics about Guatemala and labor unions. And then, at the end of the day, I decided to write personal politics, and that seems to have resonated in a

way that rewarded my laziness.

SREENIVASAN: You know, I got to ask, during the pandemic, I mean, this might be just sort of a dad pride moment. But there was video with Nandi

Bushell, who is an amazing, a phenomenal drummer and she’s in her own right, wow, right? And then, I’m watching your son play the guitar. And

about a minute into the video, like, wow. This kid can shred and there’s literally you in the background, it’s like, that’s my son.

MORELLO: Yes, yes, yes.

SREENIVASAN: Like, you’re having this moment. And how did he — what happened? How did he get there?

MORELLO: Yes. What the hell happened? Like I started playing at 17. He started playing at nine and he’s also already better at nice, you know, it

was a pandemic discovery. You know, the kids — no kid want to do — they don’t have anything nothing to do with — there’s instruments around the

house, they don’t want anything to do with it.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

MELVIN: But during — you know, during the month or two in where the days were stretching out endlessly, he’s a fan of classic — my son, Roman, he’s

a fan of like rock music a little bit. And so, I timidly suggested, you know, since we had a lot of time on our hands, would you like to learn the

first three notes of Stairway to Heaven?”

And he was like — you know, that didn’t sound like it would interrupt his videogame playing too much. And so, he did. And we built on these small

successes. And eventually, he was coming to me and saying, now, can we learn the solo to the song? And he had an ear and aptitude for it that I

had to work harder for. For him, it came a little bit more naturally. And so, now, I’m like the rhythm guitarist in the family, and he could just

blow over whatever I throw at him and it just so much — he just loses himself. He was 10 years old. He just losses himself in it. And I’m just —

like my job now — let me tell you, my rhythm guitar straps are together because I haven’t been allowed to play — he didn’t let me in.

SREENIVASAN: Tom Morello, thanks so much for joining us.

MORELLO: Hey, thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And that’s it for now. Thanks, and good-bye from London.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END