Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, our next guest, Ted Olson, is the former U.S. solicitor general who fought high-profile cases like Bush vs. Gore, the Supreme Court case that determined the 2000 presidential outcome, and, in 2013, Hollingsworth v. Perry, the case that overturned California’s ban on same-sex marriage.

He’s now turned his attention to fighting for America’s dreamers, the young DACA recipients under fire from the Trump administration. And he tells our Walter Isaacson about the value of listening to the other side in these divisive sides.

WALTER ISAACSON: Ted, welcome to the show.

THEODORE OLSON, FORMER U.S. SOLICITOR GENERAL: Thank you. It’s pleasure.

ISAACSON: In recent years, people have felt the Supreme Court has become more partisan.

Republicans are siding with Republicans, the Democratic appointees siding with others. Some of that seems to stem from the legacy of Bush v. Gore and the legacy of Citizens United, this political polarization on the court and in our society.

You were at the center of both of those cases on the conservative side. Do you worry that that has helped cause a divide, both socially and on the court?

OLSON: I don’t think so. I think that those are each an individual case. Citizens United, which many people talk about and scream about and yell about and so forth, is a First Amendment case. It is to, what degree may individuals express their political points of view with respect to writing articles or, you know, making expenditures supporting the person that they favor in terms of political candidacy?

ISAACSON: But doesn’t it let corporate money come in more than it used to?

OLSON: Well, in fact, it hasn’t. Most of the people that — most of the money that is — now people are complaining about is coming from very, very rich individuals.

ISAACSON: Is this a good thing?

OLSON: It’s not so much a good thing or a bad thing. It is a part of freedom. It is a part of our country. We let people express their point of view. We don’t say, because you have been successful, you must be quieter in the political process. We don’t object when labor unions spend hundreds of millions of dollars with respect to sending people out knocking on doors, do precinct work. We don’t let Congress handicap people because they’re better-looking, they’re better speakers, they have more money, they have more rich friends. We don’t do that. We — that’s a part of the First Amendment, gives an awful lot of license to individual disparities with respect to their skills, their standard, their background.

The greatest advantage in a political election is incumbency. But if we want Congress to start tinkering around with saying, if you’re an incumbent and your name recognition is better, you should spend less money, it gets very, very complicated. And what the Supreme Court decided — now I’m defending Citizens United. You didn’t really ask that. But it’s a matter of individual freedom when we say in the First Amendment you have the right to express yourself in the way that you want.

ISAACSON: Should the government allow, though, people who have big fortunes to have a disproportionate voice in whom we elect?

OLSON: Well, they have a disproportionate voice if they’re a powerful labor union, if they have — if they have — if — some people are really great speakers. Do they have a disproportionate voice? Some people have a name Kennedy. They have a disproportionate voice. Do we start as government deciding disproportionateness? Do we decide to handicap people like they do at the racetrack, put more weight on one horse because it’s faster? We don’t do that. In the political process, we let the First Amendment play itself out. It’s a robust thing. Now, people talk about good or bad. That’s the government that we have. That’s a pretty good government that we have had for 230 years that allows a lot of interplay in the joints.

People express — Citizens United involved a small nonprofit ideological group on the right side of the political spectrum that wanted to make a 90- minute documentary about Hillary Clinton. And the person who was behind Citizens United said, well, Michael Moore can do that on the left. He can make a movie supporting people on the left side. Why can’t I do that on the right side? It was a presidential election. Do we want to tell people you can’t — and he had 1 percent of his funds were corporate funds. Most of them were individual funds. At that point, the law would have put him in jail for five years for allowing 1 percent of that money to contribute to a 90- minute documentary about the qualifications of someone running for president of the United States.

Now, I could go on and on. But I think, to get back to your original point about partisanship in the Supreme Court, it didn’t used to be that presidents were so careful about who they appointed to the Supreme Court. People — they would get suggestions from their own political party and so forth. But President Eisenhower appointed William Brennan and Earl Warren, turned out to be very, very liberal people. President Ford appointed John Paul Stevens, who turned out to be a very liberal justice. What presidents have become aware of is that, because a justice may be on the court for 30 years, if you really want the person to be on the Supreme Court to reflect your political point of view, your ideology, then you have to be very careful on the selection process. That’s why eight of the nine justices now come from federal appeals courts. That way, a president knows how they would vote on the type of issues that come before the Supreme Court. So, it’s now more predictable.

ISAACSON: President Trump has recently said that Justices Sotomayor and maybe Ginsburg should recuse themselves because of bias.

What was he thinking? I mean, what do you think…

OLSON: You’re asking me what President Trump was thinking?

(LAUGHTER)

ISAACSON: No, no, I’m asking what do you think of that.

OLSON: Well, other people have said, Chief Justice Roberts should be recused because he presided over the impeachment trial, and, therefore, he can’t be expected — people a few years ago were trying to ask Justice Scalia to be recused because of his — he had a relationship…

ISAACSON: Yes, yes, but we have the president of the United States publicly attacking two justices. What do you feel about that?

OLSON: Well, I think that this is not a wise thing to do at all, and it’s not justified. I have practiced law for over 50 years. I have practiced in the Supreme Court for a long, long time. I have argued a lot of cases in the Supreme Court. I have never not been impressed with the integrity, the hard work that the justices all across the political spectrum — some of them have ruled against me. Some of them, they haven’t come out the way I would in a particular case. But in — without question, they’re intelligent, hardworking, honest individuals, calling them as they see them. If some president, any president doesn’t like the result — President Obama criticized a Supreme Court decision in his State of the Union address while the justices were sitting right in front of him.

And he was wrong on the facts when he did that. And, by the way, of the institutions of our government, the judiciary, the legislative branch or the president, which branch do the American people — do the American people respect? The judiciary, even if they disagree with the case. I — as you pointed out, I argued Bush vs. Gore. People disagreed strongly. It was a very close decision, very contentious, the presidency of the United States. The American people have accepted that decision. I gave speeches in Europe after the decision, and people in France and other parts of Europe said, that was so hard-fought, and the American people accepted the decision. They didn’t go to the streets. They didn’t start looting. They didn’t start to over — try to overthrow the government. This is a judiciary that’s independent, that makes decisions. And we have to respect those decisions. And we have to accept them, even though we don’t agree on the merits with the particular decision.

ISAACSON: You said, we have to respect the judiciary. And you say, as an American people, we tend to really respect the judiciary. Do you worry that the president, by attacking specific federal judges, like the one in the Roger Stone case, personally is undermining respect for the American judicial system?

OLSON: I think every lawyer, particularly, needs to defend the judiciary and come out and say, we respect their decisions. We may not agree with them. And, now, President Trump is not a lawyer, but anybody in the presidency, in the executive branch has to be very, very careful about that sort of thing. We have a way of disagreeing with judges. It’s called an appeal. We have other ways to disagree with judges. And if we could disagree on the merits, on the issue that was decided, we can write articles, we can say, we think that it should be decided differently. For every decision, there’s a loser. And that individual and the lawyers for that individual have to respect the decision. And they should say so. The framers of our Constitution were brilliant. They decided that judges will have tenure for life, so they can be independent, so they can make unpopular decisions. Well, if they were given life tenure so they could make unpopular decisions, they will make unpopular decisions. We want them to do that. They defend minorities. They defend people. They defend ideas when the — when the populace gets carried away with something and passes something that takes away the rights of individuals, the courts are there to protect that.

So, if they’re making unpopular decisions, it’s because we authorized them to do it, because they — we thought that it was good for our country and good for this government that’s existed for 230 years, that has provided a very, very sound economy and the maximum amount of freedom that anybody in the world has. So, that’s the price we pay. Once in a while, we get a decision we don’t like. Tough.

ISAACSON: You have taken on the cause of the dreamers, the — President Obama’s deferred action plan to help people who came as young kids to this country.

Why did you do that?

OLSON: It’s very, very important issue and a very, very important question. And I was very, very gratified to be asked to represent the dreamers in the Supreme Court. We have something like — no one knows the exact number, but we have something like 11 or 12 million people in this country that could be exported. They’re undocumented and so forth. Congress appropriates money to deport 400,000 per year. The dreamers are individuals who came to this country as children. They didn’t choose to come to this country. They — I talk to so many of them. Some of them came when they were 1 years old, or 2 years old, or 4 years old or 5 years old. They don’t speak the language of the country that they came from. That’s not their country. This is their country. They have been here for a long time. They have children. They have been educated. They have served in our military service.

So, if we’re going to import — deport 400,000 people a year, why would be pick them? They haven’t committed any crimes? We would — if we have to move people out of this country because they’re undocumented, you pick people that have committed crimes, or the people that are abusive husbands or something like that, but not the dreamers. They are part of our society. And it would be cruel to send them to a country that they don’t know, which speaks a language that they don’t know, that splits up their family, takes them away from their children who were born in this country and our citizens.

So there are 700,000 or so dreamers. I felt that the decision by President Obama — and he agonized over whether he would make that decision, but, basically, what he told the dreamers is that you came to this country with — when you were a youngster, you obeyed the law, you have kept your promises, you paid taxes, you have done all these things, we’re not going to deport you. We’re going to put you in a deferred category. So, you can have some semblance of normal life. You can get an education. And while you’re here, you can get a job and support yourself, rather than have the government support you.

So, then President Trump came along, who initially supported this program, and then, for whatever reason, I don’t know, changed his mind and said, the whole program was unlawful to begin with, and it’s over with, therefore, by doing that act, put those 700,000 people and their families and their employers and their children in jeopardy for being deported.

Why would we do that? These are people that — if we’re not going to deport everybody, these are the last people in the world we want to deport. And we made the argument in the Supreme Court that the president had the power to adopt priorities with respect to deportation, but he had to do it with reasonable explanations, a rational process.

We have what we call due process in this country. It was the Administrative Procedures Act. You have to explain why you’re doing that. And the decision can’t be arbitrary or capricious or just plucked out of the air. You have to take responsibility for it, explain why you’re doing it. This administration did not do that. We argued to the Supreme Court, well, whether or not you could do it, if you did it right, you did not do it right. And, therefore, that decision has to be overturned.

We’re still waiting for the Supreme Court. We argued that case in November. We don’t have a decision yet. I’m hoping it’ll come out the right way, because it is the right solution to an important problem. And I spent a lot of time with groups of dreamers and individuals. Indeed, Walter, one of the things we did, one of the members of the dreamer community had gone to law school. He borrowed his roommate’s books in order to stay up all night to go to law school. He graduated from law school. He is admitted to practice law. We arranged for him to be admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, and he sat next to me during the oral argument in the Supreme Court, the first dreamer to be admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court. Think of the symbol, this young man, who’d worked hard, created a family, now a member of the Supreme Court bar. Should he be deported? No.

ISAACSON: And in the past 15 years, you have tried to find common ground. You seem to have shifted a bit, helping the dreamers, gay marriage.

Was there a shift in your philosophy? And, if so, what happened?

OLSON: I don’t think there was ever a shift in my philosophy. I remember wanting to be a conservative Republican going back to college or even before that. But part of that — I grew up in California. Part of that was individual rights, individual freedom, respect for one another. California is a melting pot. It was then, and it is now. I was on the forensics team in college, and we debated the — you know, those debate tournaments? You’re on the affirmative one hour and you’re on the negative the next hour. And one of the things that that teaches you is to listen to the other side, to understand what the other side has to say, what the arguments are on the other side. And I think that helps understand different people and different points of view. So, I don’t think I have changed so much, but the opportunities that may come along in my law practice, if there’s something that I find interesting — and some of the cases you mentioned, I found very, very interesting — I don’t think there’s a whole lot of inconsistency there, although I have been accused of it.

(LAUGHTER)

ISAACSON: And so tell me why you took the gay marriage case with David Boies, who had been your opponent in Bush v. Gore.

OLSON: Let me back up a second say, that was November 8 of 2008. Proposition 8 passed in California, adding a provision to the Constitution that said marriage was permissible and recognizable only between a man and a woman. It took away a right of individuals in California to marry the person they loved who was the same sex. Interestingly, that was the same election that President Obama won overwhelmingly in California. So, here, California was enacting or adopting or electing, the first African-American president, at the same time was taking away rights of its individual citizens.

(CROSSTALK)

ISAACSON: Well, but even Obama wasn’t in favor of gay marriage at that point.

OLSON: He wasn’t. He wasn’t. He finally came around. But it seemed to me anomalous. And it seemed to be inconsistent with what – – I grew up in California. It seemed to me to be inconsistent with the California that I sort of really liked and loved, the respect for individuals, the respect for differences, the respect for people and keeping government out of people’s lives. So, when I was contacted about it, I thought, if I can help the individuals restore their right to their happiness, I’d be happy to do that.

ISAACSON: Respect for individuals, respect for diversity, things you just talked about, do you think conservatives have moved away from that principle of liberty?

OLSON: I don’t think conservatives have. And I wrote a long piece that was on the cover of “Newsweek” at the time I started this case, and the headline was, “The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage. And I made the point that — in that article, at some length, that a marriage between two individuals who wanted to be a part of the community, and who wanted to raise a family, and who wanted to pay taxes, that’s a conservative value. There was no reason why conservatives should be against it. Public opinion was against same sex marriage at the time by about 56 to 44 percent. It changed over the period of time that David and I handled that case. My mother, who was quite a bit older and very conservative said, why are you doing this? We sat down. We talked about it. And she later said, if you understand the issue, you will agree that it is wrong, and we need to change. And now look at this — in this country now, people think relatively nothing of it. There’s gay marriages all over the United States. And people are not threatened by that. It hasn’t threatened heterosexual marriage. It hasn’t threatened anyone. It is a happy thing that has occurred. It’s one of the really good things that has happened in the last 15, 20 years in this country.

ISAACSON: Ted Olson, thank you very much.

OLSON: Thank you, Walter. I appreciate it.

About This Episode EXPAND

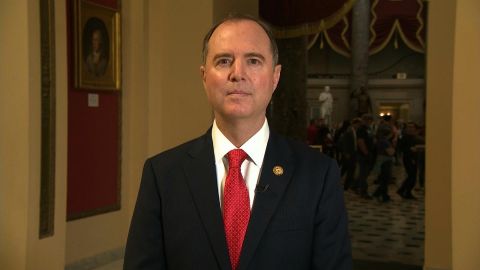

Congressman Adam Schiff gives an update on coronavirus. Journalist Lydia Cacho discusses Monday’s nationwide women’s strike in Mexico. Former U.S. Solicitor General Ted Olson speaks to Walter Isaacson about the divided state of the Supreme Court and the DREAM Act.

LEARN MORE