Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

It’s caliphate on the brink of extinction. What does the future hold for ISIS? Former head of British Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Richard

Dearlove on why the threat remains alive.

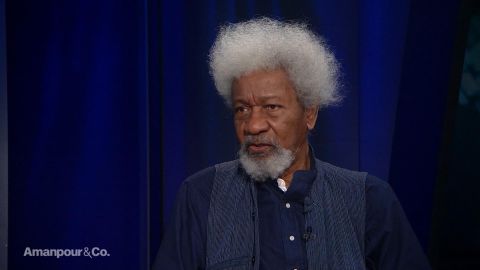

Then to Nigeria, and this weekend’s election in Africa’s biggest economy. I talk to Nobel Prize winning poet, Wole Soyinka about Nigeria’s

relationship with itself and with the United States.

Plus, the immigration lawyer who fought the Trump administrations’ travel ban. Becca Heller talks to our Alicia Menendez. She says xenophobia is at

the heart of politics.

Welcome to the program everyone, I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Civilians continue to flee the last area under ISIS control in Syria as the terrorist groups makes a final stand against U.S.-backed forces there. Its

caliphate is about to be defeated and President Trump says mission accomplished, and he plans a total withdrawal of U.S. troops.

But military and intelligence leaders of the anti-ISIS coalition are not totally convinced. Including the former head of the British Secret

Intelligence Service, Sir Richard Dearlove. He led the organization which is also called MI6 for five years during the time of 9/11 and the global

rise of radical Islamic terrorism.

In a wide-ranging discussion rare T.V. interview, Sir Richard shared with me his views of the dangers facing the West from radical Islam to Russia

and China.

Sir Richard Dearlove, welcome to the program.

RICHARD DEARLOVE, FORMER HEAD, BRITISH SECRET INTELLIGENCE SERVICE: Very nice to be here.

AMANPOUR: ISIS. You were head of MI6 during the 9/11 period, so you know all about this Islamic extreme militantism. What do you make of the

current battle? Is it the watershed moment? Is it being exaggerated? I mean, they’re talking about finally defeating every last inch of ISIS

territory.

DEARLOVE: I think it’s the military defeat of ISIS on the ground but it’s quite rare for terrorist organizations to be occupiers of territory. So,

it gives up the last of its territory, the last village in which it’s installed. But I don’t think you can say that’s the end of the terrorist

problem. That’s a rather complacent and simplistic attitude.

In fact, you could argue that as terrorist movements are defeated, if they can be, they become in their last throes, which can last a long time,

rather dangerous.

AMANPOUR: Because it’s important to try to figure this out. President Trump keeps saying that the last vestiges are being defeated. But I think

you just sort of in capsulated the difference between territory being denied and their ability being denied.

So, from your experience and having, I guess, watched ISIS, at least, from a far, what do you see is going to happen even if the caliphate is fully

and utterly removed from them?

DEARLOVE: Well, I think it goes back maybe to being a conspiratorial terrorist movement and still going to radicalize. I mean, if you are a

terrorist movement, to verify your existence you have to commit acts of terrorism. I mean, it’s simplistic statement. But on the other hand, I

would expect ISIS as loses its military fall to maybe go through a period when it’s going to try again and mount attacks that raises its profile and

reminds us all that it’s still in existence.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s now talk about Saudi and Iran —

DEARLOVE: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: — because those are two pillars of the new U.S.-Middle East strategy. So, in this regard, first and foremost, before we get to how

Saudi Arabia started to try to neutralize terrorism from within when it came to fight them in 2003.

DEARLOVE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Just from your experience, remind us how they actually encouraged all of this radicalism and fanaticism by getting rid of their

own troublesome radical mullahs and exporting them around the world.

DEARLOVE: Well, I think that was a period of time with the Saudi regime interestingly around the time that I was chief of SIS. When the Saudis

were not paying sufficient attention to — I mean, what I mean by that is that, you know, the Saudi security authorities, to the behavior of their

own Islamic organizations, which were frankly funding extremism, and they were very complacent.

I think they woke up to the reality of what they had partially caused rather late in the day. And, you know, by that stage they were willing,

for example, to talk to people like me about the problem, when initially — you know, this is pre-9/11, when we were saying, “Well, there’s a problem,”

they were saying, “Well, you know, “You’re not a Muslin and you can’t really talk to us about this because you don’t understand it,” but there’s

been a, you know, very significant change and a shift in their attitude and their thinking.

But by the time those problems manifest themselves particularly with ISIS and the buildup of ISIS, I think a lot of that money originally came

probably from Islamic sort of — the very equivalent of Islamic non- governmental organizations.

AMANPOUR: So, now, you have this situation on the ground in all its different aspects and you have a policy emanating from the White House to

sort of join up with Saudi Arabia and try to counter what the White House believes is Iran’s malign and terroristic influence.

DEARLOVE: The rearrangement of the strategic pieces in the Middle East has been so fundamental that it’s quite difficult to sort of get one’s head

around the extent of the changes.

I mean, you know, Trump has thrown his cards in like 100 percent with Saudi Arabia. You have this weird situation, you know, where the Saudi and

Israel are now strategically and closely allied against Iran and, you know, the defining issue is this sort of proxy confrontation between Iran and

Saudi Arabia. And, of course, the Americans are trying to line up as much, you know, strategic support as they can on their side of the equation.

I mean, to an extent I can understand their approach because we have created a situation through our various political interventions in a way

that Iranians have become the world’s experts and they are fighting wars just below the threshold of open warfare.

So, their sophistication, their ability to deploy the Quds Force, you know, whether it’s in Syria or whether it’s in Iraq, whether it’s in Libya —

well, I mean, not so much in Libya but in Lebanon, we have a major problem on our hands and —

AMANPOUR: Given that you believe that, and a lot of people do believe that —

DEARLOVE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — certainly the kind U.S. administration and many around the world. Is Mohammed bin Salman, crown prince of Saudi Arabia, the best

alternative, especially right now with —

DEARLOVE: Well, sure he’s the only alternative on offer.

AMANPOUR: What would you say if you were still head of MI6 — let’s just put it like this. You’re M to James Bond, for American audience, and

you’re sitting at the table and you’re thinking, “OK. Here is this issue. But, oh, my goodness, Saudi Arabia, led by Crown Prince Mohammed bin

Salman, is accused by all the U.S. intelligence agencies as well as practically anybody else who’s watching, of being behind the brutal murder

and dismemberment of a journalist. One who was a resident in the United States, working for the U.S. How do you throw your lot behind this kind of

person for such a massive — is there a contradiction in terms? Is it —

DEARLOVE: Yes, there is. Morally with great difficulty. But I think, you know, in a way I would argue that Iran is forcing the West to make

strategic choices. What is the alternative? I’m not sure. I mean, the conundrums of making policy on Iran and the Saudi Arabia are well-known to

anyone who’s been involved. And it’s very, very difficult to develop strategic options, frankly, if you take a moral standpoint.

I’m deeply shocked by what happened to Khashoggi. But I mean, I’ve dealt probably more than — most very closely with the Saudi regime, and upclose,

it’s not a pretty sight.

So, maybe some of us would not quite — it’s a particularly ghastly, a shocking incident. But I mean, look —

AMANPOUR: You’re trying to say you weren’t surprised?

DEARLOVE: I’m sorry to say I wasn’t surprised.

AMANPOUR: Wow. Are you surprised that the president of the United States does not adhere to, listen to, respect, take on board the consensus from

his own intelligence agencies on who was likely behind that despicable murder and dismemberment?

DEARLOVE: Well, I mean, I think you have to make a distinction what he might have said privately and what he says publicly. I think it’s very

hard to contest the evidence as we’ve seen it in the public domain.

AMANPOUR: In general, as a former intelligence chief, when you see the president of United States, and it’s not just on this, it’s on Russia, it’s

on many, many other things, the president dismissing the expert advice of the consensus of his intelligence operations. Does that trouble you?

DEARLOVE: Of course it does, yes.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you about another really difficult issue and that’s cyber war and all the other things which many people are worried about.

So, the U.S. is warning governments against the Chinese tech from Huawei, which is spending about 2 billion in the U.K. to address security concerns.

Let me just play what the secretary of state has said about Huawei and we’ll get your opinion on that.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MIKE POMPEO, U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE: What’s imperative is that we share with them the things we know about the risks that — Huawei’s presence in

their networks presents. It also makes it more difficult for America to be present, that is if that equipment is co-located to places where we have

important American systems, it makes more difficult for us to partner alongside them.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Again, another very complicated set of relationships. What do you read into that?

DEARLOVE: Well, I largely agree with what Pompeo is saying. It’s taken us quite a long time to wake up to the threat from the Chinese, the lies, you

know, in their supply of technology to the world. And the Australian government, I think, were the first to take a clear stand, there is a

danger.

I mean, it’s not this is an immediate danger but, you know, if China aspires to superpower status, there may come a time further down the road,

you know, when we discover that software and the hardware that we’ve bought from them is trapdoored in ways that we may not have clearly understood

when we bought it.

I really think that the general alarm that is being sounded about Huawei is sensible. And I think is important that the Chinese sit up and listen

carefully because it may be that — you know, there’s a lesson for them in this and that in the future we can handle the problem differently.

AMANPOUR: So, when you look around, particularly from an intelligence point of view —

DEARLOVE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — and that you look at the threats and you assess the risks, et cetera, what is your biggest nightmare, your biggest concern? What keeps

you up at night?

DEARLOVE: Well, I think most definitely, you know, terrorism was to the forefront. I’m not sure that it is any longer.

I think China’s rising status to superpower and its behavior in its own area of influence and I think, you know, the decline of Russia and Russia’s

ability to behave really in an extreme fashion in its own area of influence.

AMANPOUR: Is President Putin getting the message?

DEARLOVE: To an extent, probably yes.

AMANPOUR: What do you make of him though using poison gas here, right on our doorstep, here in Salisbury, against (INAUDIBLE) and others — not

poison gas, you know —

DEARLOVE: It’s outrageous. But the Soviet regime, the Russian regime, murdered its dissidents and opponents, you go back to Trotsky, I mean,

that’s exactly to attain —

AMANPOUR: Continuum?

DEARLOVE: Yes. And what’s interesting, you know, about the Skripal. I mean, Skripal, I think, would have been safe in the Cold War because there

was a sort of — and I wouldn’t say there were of rules, tehre were set of constraints. Those constraints that we recognized in the Cold War

situation seemed to have been removed.

So, Skripal, who, you know, had been released from prison had been exchanged in a prisoner exchange or a spy exchange, you know, you would

have thought, “Well, he’s quite safe,” well, clearly, the Russians thought differently.

But although, you know, he was resettled in the U.K. and clearly, it had a role in the intelligence. I’m not going to comment further on that.

AMANPOUR: Your must have known about it?

DEARLOVE: I’m not because I talk about. (INAUDIBLE) don’t say. I did interview. Well, I mean, you can you see the Skripal affair is pretty

peculiar then.

AMANPOUR: Well, it shows the long arm of President Putin.

DEARLOVE: But it shows the long arm. And I think the thing — the point I was going to make is, you know, he — they were to see him as a Russian

citizen. So, if you look at their record of assassination, almost all, you know, through the Cold War, pre-Cold War —

AMANPOUR: How helpful was Skripal to the British?

DEARLOVE: I think I’m not going to comment on that. I have a —

AMANPOUR: Fair enough. Now, Brexit, which I know you support and which the whole world is looking at and I’m not sure what you feel now about

where it looks to be going, whether you are a hardline Brexiter and you don’t mind about a no-deal.

But in any event, the director of U.S. National Security, Dan Coats, addresses Senate, and he actually mentioned Brexit it in the first sort of

10 minutes of his address when ISIS was also the main issue of discussion, he was talking about world threats. Here’s what he said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAN COATS, U.S. DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE: Well, the possibility of a no-deal Brexit said in which the U.K. access the E.U. without an

agreement remains. This would cause economic disruptions that could substantially weaken the U.K. and Europe.

We anticipate that the evolving landscape in Europe will lead to additional challenges to U.S. interests as Russia and China intensify their efforts to

build influence there at the expense of the United States.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: You know, that’s a concern. We’ve just been talking, you and I, about Russia and Chinese threats and he’s basically saying that the

uncertainty and a hard Brexit could complicate the threats.

DEARLOVE: I disagree with him. I think, obviously, a hard Brexit lead to some economic disruption. I just wonder whether that hasn’t been

exaggerated. So, for that point of view, yes, there would be a weakening.

But. I mean, I’ve argued that I think in secure national security terms, us returning to the Mid-Atlantic will not really change much in European

security, the U.K. remains Europe’s leading defense and intelligence power, we have very, very strong bilateral relationships with all the E.U. member

states, particularly with France. I don’t think those are going to change after Brexit. In fact, I think, you know, they might even be strengthened.

AMANPOUR: So, you — I think you do stand out as being one of the rare security and defense chiefs and intelligence chiefs who actually support

Brexit.

DEARLOVE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You’re pretty much alone in that regard because most of that establishment doesn’t think it’s healthy for Britain or for Europe for that

matter. And I actually spoke to John Sawers, one of your successors, and this is what he said about what you said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOHN SAWERS, FORMER HEAD, BRITISH SECRET INTELLIGENCE SERVICE: People in senior positions have different perspectives on this. I would only say

Richard Dearlove left the intelligence world 12 years ago. And the way in which we conduct counterterrorism cooperation Europe is completely

different now from how it was back in 2004 and I think it’s much, much more effective than it was when he was in charge of MI6.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, he’s basically saying you’re an old fogy and actually, that was now it would be 15 years ago that you left and they don’t quite get the

alignment as it as it stands right now and the risks to Britain in this break up, in this divorce.

DEARLOVE: I think I do. I think I understand the problem very well. And a certain amount has change, particularly in terms of data exchange. The

more sophisticated capability we have to track stuff internationally.

I spent nearly 40 years doing this. All I would say is I have great respect for John but he was a diplomat not essentially an intelligence

officer. I spent a lot of time with people like Salana (ph) talking about E.U. capabilities and how we could support them but we wanted them to be of

a specific character, which they are now, and the meat of European security for very good reasons of security is done on bilateral links.

AMANPOUR: So, you’re a bilateralist. It isn’t like Trump. You’re Britain firster?

DEARLOVE: Yes, I am.

AMANPOUR: You don’t care about a no-deal?

DEARLOVE: I didn’t mind about a no-deal.

AMANPOUR: OK.

DEARLOVE: But there are plenty of historical examples of countries on their own doing well in very adverse circumstances. If you’re a historian,

you only have to look at the Venetian Republic or Singapore. I know the Worlds Trade.

AMANPOUR: That was hundreds of years ago.

DEARLOVE: Maybe. But —

AMANPOUR: There were no such unbelievably close links and Britain have 40 years of this, 45 years of this.

DEARLOVE: Yes. But it was a phase in our history.

AMANPOUR: Sir Richard Dearlove, thank you very much.

DEARLOVE: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Mass population flows and refugee crises are another major national security concern facing Western countries. And our next guest,

the immigration lawyer, Becca Heller, has been on the front lines fighting against President Trump’s travel ban on predominantly Muslim countries.

Winner of the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant for her work protecting refugees in the U.S. from deportation, Heller has been speaking to our

Alicia Menendez about her ongoing mission to represent displaced people and immigrants in the Trump era.

ALICIA MENENDEZ: Becca, thank you so much for joining us today

BECCA HELLER, CO-FOUNDER, INTERNATIONAL REFUGE ASSISTANCE PROGRAM: Thanks for having me

MENENDEZ: So, our domestic conversation around refugees has focused largely in the recent weeks and months on migrants coming from Central

America. But before that dominated headlines, there was the so-called Muslim ban, you were corralling resources to act at their disposal. Can

you take me back to that moment?

HELLER: Yes. I mean, one thing that’s worth pointing out is that there is still a Muslim ban, so-called or not so-called, it’s still in place. It’s

preventing millions of people who otherwise should be eligible to come to the U.S. and reunite with family members or get critical treatment for

diseases from coming in. I think it’s been lost in the narrative shuffle quite a bit, but it is it is currently being enforced and keeping out tons

of people all the time.

When the first version of the Muslim ban — because now, we’re on version, you know, 3.5 or 4.5, depending on how you count, came down, my group, the

International Refugee Assistance Project, organized all the lawyers who went to the airport to try to make sure that people weren’t illegally

detained and deported and we were, you know, I think largely successful in the first few days at preventing kind of large scale deportations under the

ban.

MENENDEZ: Can you draw a line for me between the crisis in Central America, the Muslim ban and explain how these two stories fit together?

HELLER: I think that you have an administration that, for whatever reason, has decided that the heart of its policy is going to be the xenophobia and

that the best way to rally support for whatever affirmative policies they want to hatch, which has yet to be seen, that the best way to generally

rally support for that is to discriminate against immigrants.

And I think that, you know, those immigrants tend to predominantly be from, to use the words of our own president, — countries and that’s who’s

bearing the brunt of this and that’s countries in the Middle East and North. Africa and that’s countries in Central America and it may start to

be other countries as well.

But I think it’s mostly countries that produce a lot of refugees and forced migrants trying to come to the U.S., I think it gets defined backwards.

Basically, if you’re trying to get in, we don’t want you.

MENENDEZ: What is the biggest misconception about refugees?

HELLER: Oh, there are so many big misconceptions about refugees. I mean, I think, you know, the right and the left each have their own set of

misconceptions. I think there’s a series of misconceptions on the right that, you know, refugees are terrorists, that refugees take American jobs,

that refugees are a strain on the economy.

I think there’s similarly a set of misconceptions on the left that refugees are sort of these needy helpless victims and that the reason to take

refugees in is that we have some sort of like moral obligation to help them as they’re like strong international brethren, and I think that that’s sort

of like equally ill-conceived.

MENENDEZ: There’s been a lot of attention on this question of family separation in light of the Trump administration —

HELLER: Right.

MENENDEZ: — policy of separating children from their parents at the border. And yet, there is this lingering question of whether we, as a

country, believe in full family reunification and whether or not that should be a priority of our immigration system.

HELLER: I think that most immigration policies in most, you know, so- called like democratic countries focus on bringing families together, like the core of any immigration system is that if I’m here and I have family

who somewhere else that I should be able to bring my family here so that we can be together.

I think that part of why people were able to get so activated around the issue at the border is that, you know, they were able to go witness it,

right. It was not dissimilar to the situation at the airports where, you know, you could go to your local airport and be with a mass of people and

sort of — not that you could see people detained but you could see the airport is sort of the symbol of what was happening.

And journalists were able to get photos of kids in cages and kids being separated from their parents. And it was that kind of imagery and access

that made it possible to have such a visceral reaction. Whereas, if families are still separated as opposed to if like the U.S. is actively

separating them, it’s much harder to document in a way that gives people that visceral reaction.

MENENDEZ: For example, the Yemeni mother who was able to finally visit her dying son in the United States, I mean, that story didn’t get nearly as

much attention as what is happening on our Southern border.

HELLER: Yes. But I think — so that — in that case, there was a there was a two-year-old Yemeni boy, and I believe Oakland, who was dying and his

mother couldn’t come be with him because of the Muslim ban. She applied for a visa to be with her dying son and she was rejected, and that is

actually illegal even under the terms of the ban itself.

Because the ban says in exceptional circumstances like if your — and it doesn’t spell out this precise circumstance but it gets awfully close, if

you’re a mother and your kid is in the U.S. and dying, we will make an exception. We will give you a waiver and say, “Yes, you can have a visa

and you can still come in,” and they didn’t do that for her.

And part of the reason for that is that there is no real waiver system, and that’s something that’s being challenged in courts right now. But I think,

you know, there were three straight days of headlines in a lot of newspapers saying this woman should be able to come in.

And one thing that really struck me is that I think it’s pretty unusual for there to be three straight days of headlines about Yemen that aren’t

talking about like terrorism or famine or civil war or drone warfare, et cetera, they were literally just talking about this mother who needed to be

with their child. But I think, also, the reason that it ended quickly was that it only took three days of public attention for the administration to

just completely reverse itself.

It didn’t take a lawsuit. it didn’t take an act of Congress, it was just three days of public outcry and then they turned around and they gave her

her visa. And I think in the case of child separation, it was the same thing, where, at the end of the day, the administration reversed itself, at

least publicly, we’re now finding out that privately and, in fact, did not reverse itself very much, that there are thousands more children that were

separated from their families that we even know about.

But, you know, publicly the administration reversed the policy simply in response to like a massive public outcry but it still took weeks and weeks

of newspapers, just relentlessly covering it and people going to the border. But in the end, you know, the public outcry worked.

MENENDEZ: You often say that your work is apolitical and I wonder to that end if you can cast —

HELLER: Yes. Don’t I find apolitical right now?

MENENDEZ: — a retrospective critical eye on the Obama administration, when he himself was called deporter-in-chief, when you look back at the

policies of that era, in what ways have they softened the ground for the policies that we’re seeing now?

HELLER: Yes. Obama deported more people than any other president before him. and I think — you know, I don’t have the statistics at my fingertips

right now, but I think, you know, in the first year or two of the Trump administration, he still wasn’t supporting as many people as Obama did.

And, you know, things like the use of tear gas on the border, the, you know, mass detention of children on the border, like these were not things

that began with Trump. These were things — and they weren’t things that began with Obama. You know, they were policies that Obama continued. Like

we — we’re not great with immigrants in this country. We have a long history of treating immigrants pretty badly dating back to before the

Revolutionary War really.

So, I don’t see the mistreatment of immigrants as a partisan issue or even necessarily as a political issue. I think it’s been hijacked as a

political issue like —

MENENDEZ: So, then, what would it look like to get this right?

HELLER: To get immigration policy right? I mean, I think families should get to be together. I think that you can’t look at immigration policy in a

vacuum, right. I think if you’re talking about policy on the southern border, you can’t talk about that without a discussion of like what is our

economic and foreign and military policy in Central America.

And I think all these questions about like how many people should come over the border and whether the border should be open or not, like it’s sort of

missing the larger context of the role that we’re playing in creating a migrant crisis in the first place. If our economic policies are creating

dependent economies where there are no jobs, I don’t think we should be very surprised when people leave those economies and come here looking for

jobs.

MENENDEZ: It does for many people come down to this fundamental question of how many people should be allowed to come into the United States. How

do you sir that practical question?

HELLER: That’s just not how our current immigration policy works even. Like a lot of the — a lot of our sort of vectors of immigration policy of

how people come in don’t have caps. So, even the status quo, like the way that we designed the immigration policy isn’t based on this idea that like

a certain number of people should be able to come in every year.

And if it were, you still want to look at like what types of people are coming in and balancing that, right. Because, for example, like a lot of

spaces are reserved for people to come in and like be doctors at hospitals, which is something that we really need. And, in fact, like since the

travel ban and since the crackdown in immigration policies there have been a bunch of articles about how hospitals, especially in like sort of the

Rust Belt area, can’t get enough doctors and nurses to come in because people don’t want to come work here.

Similarly, with like H1Bs, that’s for people to come work at tech, we’re losing a lot of people who are going to Vancouver instead of to California

now because they don’t want to be in the U.S.

So I think it’s not — you can’t look at it as just one number and say like the U.S. should take in 2 million immigrants a year because a

lot of it should be about like determining both the needs of kind of immigrants to come in but also the U.S. really needs immigrants.

Like we need people to come in and help with agriculture. We need people to come in and study. We need people to come in and just make our country

a more sort of, you know, urbane, cosmopolitan, diverse place.

MENENDEZ: This question of refugees, resettlement, displacement is a global question at this point. Looking at this globally, what is the

greatest challenge facing refugees in the work that you do?

HELLER: I think the greatest challenge facing refugees today is that they’ve been hyper-politicized by the sort of outright movement all over

the world and made scapegoats. And so, you know, people are really afraid to let them in.

I think in the U.S., across Europe, you know you have elections being decided on refugee policy. Like you can look at Germany and see sort of

the rise of the Minister of the Interior over Angela Merkel and say that’s about refugee policy. And you can look at the rise of far-right

governments in certain Eastern European countries and say that’s about refugee policy.

I think that’s really hard to contend with and it prevents a lot of forward movement. I think everyone agrees, no matter where you sit on, you know,

pro-immigrant, anti-immigrant, close the border, open the border, like everyone agrees that the system is broken.

But I think as long as we’re in this sort of hyper-politicized hate-filled, blame-throwing environment where we like can’t even sit down and have a

rational conversation, it’s going to be impossible to change the system one way or the other. And I think that’s the biggest challenge today. I think

the biggest challenge in two years is climate change. I think that the, you know —

MENENDEZ: In the sense that it displaces people.

HELLER: Right. I think the most immediate major effect of climate change on like my generation is going to be that certain places aren’t going to be

inhabitable anymore, right. Islands will be underwater or people who live in desert, it will be too hot to live there. Places will become ravaged by

disease.

None of those people fall under the traditional guidelines of what it means to be a refugee because those were written after World War II with a very

specific political situation in mind. And there is no plan for how to deal with this.

And I think that’s a really big issue that the whole world is going to have to deal with because people are going to end up somewhere. Like if your

island is underwater like you’re going somewhere. And I think we need to start really seriously thinking about where that is and how you can get

there in a safe way that doesn’t involve like a raft or traffickers or smugglers or coyotes, you know, are being turned back by Interpol.

MENENDEZ: This started, you were a law school student, right? 2008. I’m sure you did not imagine that this would become what it has become. You

have been honored with a MacArthur Genius Award. What is it about your work that makes it so unique?

HELLER: I mean I think a lot of things about our work make it really unique. I think one is sort of the legal angle. You know when I first

started — I’m really obsessed with the fish and sea and I was not interested in starting an organization. I think a lot of people go to law

school because maybe they don’t know what else to do.

I went to law school because I wanted to be a lawyer. And as it turns out, when you’re running an organization, you’re not really lawyering at all.

And so I spent the first year just trying to figure out like who else is doing this because it seemed kind of obvious to me, you know, your big

problem is legal.

Like if you’re in Syria and you’re going through like a hearing that’s going to determine whether you get to leave Syria and go to Canada like

you’re basically on trial for your life, right? What do you need the most? You need to make sure that trial is fair and you need to make sure you have

a good lawyer. Like if I was on trial for my life, that’s what I would want to.

And it took over a year to just kind of realize that no one was doing this. I think we have this really unique model of engaging law students and

lawyers all over the world to use technology essentially to provide representation to refugees and places where ordinarily they wouldn’t be

able to get it.

And then I think our model of combining kind of direct legal aid for a large number of refugees every year with more systemic kind of advocacy

litigation work is a way to take a more like interdisciplinary approach to the problem where we see sort of like where are the individual kinks where

people are getting tripped up and then where can we try to go in and fix those.

So we’re not just saying, you know, the answer is to let more refugees and then like hammering on that one really broad point. We can say like it is

really silly that to qualify for this visa for interpreters from Afghanistan, you have to get an original signature from Kabul to Nebraska.

That’s not possible when the Taliban is reading all your mail. Why don’t you just take an electronic copy of a signature?

And that suddenly opens the door for 5,000 people, you know. You can sort of take advantage of being like a legal nerd to find like technical fixes

in the system that can actually open the door for a huge number of people that just like no one has noticed because they haven’t walked through the

system that many times.

So I think taking advantage of the fact that we’re huge dorks have been pretty helpful.

MENENDEZ: Becca, thank you so much.

HELLER: Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: Now, the Trump travel ban includes some African countries, a continent which America has a complicated history with. Especially under

the current administration which has denigrated some of those countries and which seeks to conduct a purely business relationship with others.

For instance, Nigeria, it’s Africa’s most populous country and its biggest economy as a major oil producer and a hotbed of Boko Haram terrorism and

also beset by endemic corruption. What happens in Nigeria has a major influence and significance for the continent and the world which is why all

eyes are on this weekend’s presidential election there.

And to get some perspective on this pivotal vote, I spoke to Nigeria’s poet laureate and the first African ever to win the Nobel Prize in Literature,

Wole Soyinka.

Wole Soyinka, welcome back to the program.

WOLE SOYINKA, WINNER, NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE: That’s true.

AMANPOUR: Good to see you again, particularly at this time as there’s going to be yet another election in your country. How important is this

one do you think?

I mean is the last one where we saw the first peaceful democratic transfer of power, one party lost, another party won, and there was no, you know, no

shooting in the streets so to speak? How much does this one matter in that in the theme of things?

SOYINKA: First of all, in the last time, it was not that peaceful during the election but at least the transition, that’s very important. And so a

follow up would consolidate a kind of Democratic acceptance on a level which is, of course, desirable for everybody. So it is important from that

point of view.

And also, it’s crucial in the sense that the two major parties have become more or less indistinguishable. And so I tend to see it as a contest

between more or less one party and the rest.

AMANPOUR: Do you think the age in the era of coups and violence and military dictatorship are over for good now in Nigeria?

SOYINKA: I believe that in Nigeria, the military cannot attempt to come back and find — will find they’re not acceptable. But we — there’s still

too much militarism in thinking in the government.

AMANPOUR: What does that mean?

SOYINKA: In other words, over-centralization. Under the military, everything was virtually centralized and even the governors. Some of the

civilian governors behave exactly like military governors. Another center itself, the black culture of dictation still continues, you know. But

after so many years, nearly a whole generation of military rule, it’s not too surprising.

AMANPOUR: You have entered this political fray. You back a certain organization. Is it called the Citizens Forum? You had that. And you

have basically decided not to throw your weight behind the two main established candidates who is 70-plus-years-old, both of them, and to back

a new younger one.

And you sort of written a little bit about what Nigeria and Nigerian politics must look like to the rest of the world. I just wonder if you

wouldn’t mind reading in that distinct — undistinguished voice of yours what you feel.

SOYINKA: Oh. Thank God it’s most negative. All right.

Beyond her borders, Nigeria is a tale of citizens designated pariahs of the global community for whom special dossiers are opened, and units of

security agencies are specifically assigned. Humanity litters the sand trails of the Sahara, it lines the Mediterranean Seabed with the bones of a

desperate generation, seeking green pastures. Lines from my poems have been appropriated and embossed as epitaphs on the tombstones of Nigerians

washed up the isle of Catania and accorded dignified burials by total strangers, certainly paid more respect than Nigerians themselves consider

due to their own humanity.

AMANPOUR: I think that is really dramatic, particularly as you depict this wave of people who are trying to get to the west, who washing up

on the beaches of various Mediterranean lands, it’s really profound.

SOYINKA: It’s true. Unfortunately, it’s true. I’ve been involved on so many levels with this exodus. It’s not Nigeria alone.

AMANPOUR: No.

SOYINKA: But I’m afraid we form quite a large proportion of those who perished in the Mediterranean.

AMANPOUR: So why is it Nigerians? Look, Nigeria has a very very strong economy. It has a Nollywood, a great film industry. It has great writers.

It has — you know it’s a rich country. It’s I think the most populous country in Africa. Why are people trying to escape?

SOYINKA: Well, it’s — it narrates the frustration of people like myself because we see the potential. I meet Nigerians everywhere. Go to Dubai,

go to the United States, go to South Africa, go to Australia, there’s nowhere on this globe you do not find Nigerians.

And when I say Nigerians, I’m not talking about the crooks, the criminals. We call them the 419s and so on. I’m talking about really talented

Nigerians. And the front of this talent, this brain, this brain part is not inside the country.

And I believe that the leadership we’ve had so far just does not recognize the enormity of this problem. We are like a nation of potential. I mean

how many decades are we going to live on potentiality rather than performance?

AMANPOUR: I mean let me just read you a few statistics because it is, you know, it’s a really important, important country. I mean let’s just say,

you know, gender parity. Women only hold 5.29 percent of the seats in Nigeria’s assembly.

Let’s just talk about, you know, the election. Millennials make up of the 60 percent of Nigeria’s 160 million citizens. Most of the population is

under 40. The two main candidates are 70-years-old.

And you’ve said your country desperately needs a committed idealist who can build a team around himself or herself and just tell these old fogeys to go

and take a rest. I don’t romanticize youth. I’m just saying I’m tired of my generation.

SOYINKA: Yes, I am. I’m tired of myself even. You know I’m tired of my voice. I’m tired of this Sisyphean cycle of existence. And I think we

just knew — we need new thinking, a new direction. It’s about time.

And part of this is the fault of the young generation themselves. Nobody is going to hand over power to them. And so we try to encourage new

things, not just by age alone, but just encourage equally frustrated but talented but capable people to come out and give these old fogeys a fight.

AMANPOUR: You know Nigeria is very much very well-known for many things, the whole gamut, corruption on the one hand and yet writers like yourself,

Nobel laureates Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, I mean trailblazers, people who are really on the cutting edge and are famous around the world, it’s known

for Boko Haram, terrorism and a lot. What do you think the relation — how should the world look at Nigeria?

The United States, as you know, one of the things it’s known for is President Trump basically lumping all these countries in a so-called you

know what. I don’t want to say it frankly but he made a vulgar reference to African countries including yours. But what is the right relationship

for the U.S. or the rest to have with your country?

SOYINKA: Well, first of all, there’s got to be a realistic approach. In other words, no glossing, no romanticizing. And at the same time, no

Trumpian relegation to this cesspit of history, which is complying. And many people do that.

This is one of the reasons why you still have quite a lot of foreign interest, business interest, technological interest as one goes so to speak

of us tend to come in and say we’ve seen something which the others, you know, didn’t see and they try.

So it’s a question of — a mixture of self-interest. And no businessman comes to you, here’s our country, to go somewhere else. Unless, of course,

there’s something in it for them.

AMANPOUR: I mean it’s quite well-known that you cut up your green card, your special visa when he got elected.

SOYINKA: Yes. Before — I saw what was happening. I listened to this man, know his racist theology, you know, naked, unabashed. And it wasn’t

so much against Trump. It’s really my disappointment with the American people, you know.

Yes, and it may involve — like many of us, I’m a black man and the diaspora is part and parcel of me. And the struggle of the Americans for

their own liberation was a struggle on the continent and some achievement have been made.

And then we saw an individual, listen to this individual literally trying to take that country back to those ideas, the ’60s, the ’70s, and late

’80s. And so I said if you like this man, I’m going to cut up my green card. I didn’t say I was going to abandon, leave, ask for a complete, no.

But I did and now I have a regular B1/B2. There’s no fight between me and the embassies at all. They’re very courteous, understanding. I handed

them the pieces of the green card and they gave me a B1/B2 which, you know, is a kind of status.

AMANPOUR: And I know. And you’re on your way to the United States, to New York —

SOYINKA: Yes, correct.

AMANPOUR: — in the midst of all of this that you describe. But I wonder whether you think that, especially since President Trump became, you know,

President, you’ve noticed a sort of a pushback. For instance, Black Lives Matter. For instance, the young people taking back, you know, their right

to life from gun violence.

For instance, you know, it’s not OscarsSoWhite anymore. There are all these amazing films by black directors, black actors, which are, you know

flooding the award seasons now. Major newspapers or magazines have got much more diversity at the top like at the editor level. How do you see

that going? And do you think it is a reaction to these times right now?

SOYINKA: I believe it is. I mean the — I think Americans know that they have made a terrible mistake. And so this generation you’re talking about

produces this thing. I’ve been looking – I suspect for a way of just putting Trump aside, saying this is just a bad season for us.

Let us at least make sure that we’re not saltified as people, as producers, as leaders in many many directions. And so this reaction to this is to I

cannot breathe that period of American regression. The violence, state violence, the agency violence against the blacks and the minorities. This

xenophobia which expresses itself so coldly in ways in which most civilized societies, you know, transcend it.

And so this development we’re speaking about is one which I’m hoping I will see replicate in my own society. When this young productive generation

says let’s all stop, please salvage something even while we’re struggling to get the political order together.

AMANPOUR: I mean it all sounds nice. You say though that the Americans know they’ve made a terrible mistake. But President Trump still has, you

know, in the 40 percent approval rating.

SOYINKA: Yes. You know the rhetoric of exclusion is very, very easy to infect the people with. What’s happening in the United States, we see it

happening elsewhere.

AMANPOUR: I mean we’ve talked a little bit about this election and your struggle and things. I mean I just — you know, as we’re sitting here

talking, are you actually optimistic after, you know, being on the frontlines of the struggle for your own country’s independence and

democracy? Are you optimistic about Nigeria?

SOYINKA: I’ve given up on expressions like optimism and pessimism.

AMANPOUR: Are you hopeful?

SOYINKA: I just take — including hopeful. I’m hopeless. I become very pragmatic.

OK, this is the situation. These are the cards we’ve been dealt with by history, as well as by leadership and even by foreign self-interest. So

these are the facts on the ground.

I say to the new generation, it’s up to you. We’ve taken it as far as we can and you better take hold of that till and don’t let go.

AMANPOUR: But you are, I think, 84-years-old?

SOYINKA: Yes, I’ll be 85 soon.

AMANPOUR: Eighty-five, 84. I mean you’re not slowing down. You’re not giving up the struggle.

SOYINKA: Well, one needs to breathe. You know, I kind of breath different kinds of breathing. I can breathe fresh air.

And as long as I need air, I like the air to be reasonably purified, clean, not too much. I’m not too idealistic. Just sufficient for me not to feel

ashamed of myself, feel ashamed of belonging to a hopeless society. And I think that’s what keeps me going.

AMANPOUR: There’s just so much conversation these days about colonialism, neocolonialism, the fight, the struggle, what symbols should remain, what

shouldn’t, and all the rest of it. But again, describe your struggle, your role in the struggle for your own country’s freedom.

SOYINKA: I am more interested, for instance, in what we make of our own history and what we emphasize. In Nigeria, for instance, when I go

to Abuja, and I —

AMANPOUR: Which is the capital.

SOYINKA: The capital.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

SOYINKA: And I see a street, a hospital, I see institutions being — still carrying the names of some of the most villainous leaders like Abacha, you

know —

AMANPOUR: Local. Because I mean Nigeria —

SOYINKA: Nigeria, yes, former dictators.

AMANPOUR: Not former colonial masters.

SOYINKA: No. Yes, I’m talking about

AMANPOUR: Your own?

SOYINKA: — our own monsters.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

SOYINKA: So what moral right do I have to go to Oxford or Cambridge and say, “Remove the statue of Rhodes” when we have not cleansed our own

environment of uninhibited history. And the existence of those institutions is a lesson in our challenged leadership again and again,

including the Minister of the Abuja Capital Territories.

Why is this street — I said this to the present president, you know, the one meeting we’ve had. I said what do you say against corruption. And

again, the avenue which leads to Aso Rock, Bezanin (ph) of the most —

AMANPOUR: To your palace?

SOYINKA: To the —

AMANPOUR: Presidential palace, yes.

SOYINKA: Local White House, the Black House. Bezanin of the most corrupt leader we’ve ever known.

AMANPOUR: Just more broadly because you’re an intellectual. What do you make of this sort of snowflake culture on campuses or this culture whereby

you can almost say nothing anymore for fear of being offended, there needs to be safe spaces?

SOYINKA: Yes. I know — is that the one that called political correctness these days?

AMANPOUR: Safe spaces or you could call it whatever you want but my right not to be offended.

SOYINKA: Well, that’s a great era. That’s a great era. We’ve got to learn to give offense if we believe that we’re on the right side of

history. I don’t believe in — if a murder has been committed in the name of anything, and this includes religion, you’ve got to attack the murderers

and then you’ve got to tell them that if you say that’s what your religion teaches you, that then your religion is wrong.

I’m very fond of saying to people, for instance, when they say — when they ask the question what does Africa teach the world. I say this zone of

spirituality. If you go to Africa, you will not find your religion which unlike Christianity and Islam paths a war on behalf — kills people on

behalf of religion.

So people should come to Africa, at least that much, we can both stop. And I make the most of it at every opportunity.

AMANPOUR: I just want to sort of to remind people of what you went through, solitary confinement and all the hardships you went through in

this struggle. And just, you know, throughout your many works, one of the most constant themes is what you say the oppressive boot and the

irrelevance of the color of the foot that wears it.

SOYINKA: Yes. I think dictatorship is dictatorship. Torture is torture. Leadership alienation is alienation everywhere. The relegation of human

beings to stop humanity by anyone, you’re informing the commonality is on the same level.

But one feels the pain more when that is not being administered by your own people, with whom you’ve already undergone some very negative history.

That for me is double treachery.

AMANPOUR: Well, what was it like being in prison? How did you make it through solitary confinement?

SOYINKA: I invented my own world with what parts, elements there were in my little surrounding, played mental games, just did my best to keep sane.

AMANPOUR: You wrote in your prison memoir that the man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.

SOYINKA: Yes, indeed. Still, I believe that very strongly. It’s a question of being able to live with yourself. If somebody next door is

being deprived of his or her humanity and you do nothing, how can you live with yourself? You’re already reduced as a human being.

So sometimes that part of what I do is very selfish. I want to be at ease with myself. I want to be able to enjoy what I do, my writing. I want to

be able to enjoy my beer, my glass of wine with as little, you know, external mental oppression as possible. So it’s all self-interest

ultimately.

AMANPOUR: Wole Soyinka, thank you very much indeed for joining us.

SOYINKA: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Wole Soyinka there reflecting on the nature of humanity and the importance of speaking out.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END