Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Western democracies besieged by extremes from violence on the streets of France to paralyzing political infighting in Britain to divided government

in the United States. Can the center hold against this rising tide of nationalism? Former Greek Finance Minister, Yanis Varoufakis, tells me

about his plan to build a progressive way.

Then, iconic fashion designer and activist, Stella McCartney, who says luxury designers and fast fashion must unite to save the environment.

Plus, shell shock, the emotional war that soldiers face even after coming home from the front. Our Hari Sreenivasan talk to a retired veteran and the

producer behind a new docuseries, “The War Within.”

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The leaders of Europe’s three biggest democracies, the biggest economies, are reckoning with populist upheavals, while the United States faces

chaotic divided government. It seems like the only thing uniting the West these days is division with little room for a centrist voices all

bipartisan compromise.

Look at Britain, Prime Minister Theresa May has overcome a motion of no confidence that was triggered by members of her own party who want a hard

Brexit. To placate those dissenters, she had to vow not to lead her party to the next general election.

Similar to Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel, whose own hand was forced to nominate her successor as party leader after 18 years at the helm.

Meanwhile, the French President has been rocked by the biggest crisis of his young presidency. The violent yellow vests protest described by the

country’s government as symptomatic of a European (INAUDIBLE) caused by low wages.

And the United States is trapped in its own dysfunction and divide, seen this week during a very public display of policy differences between the

president and prominent Democrats, Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi.

So, why now? Why are these political extremes so pervasive?

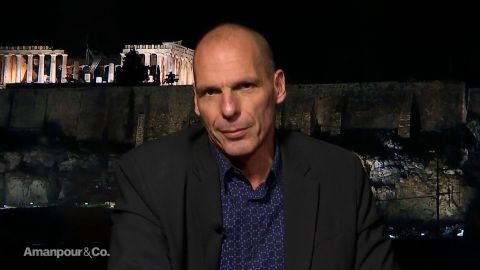

My next guest is launching his own global counter movement while also running to become a member of the European Parliament. Yanis Varoufakis is

the former Greek finance minister who resigned in 2015 amid contentious debt negotiations at the time with the E.U. and he’s joining me now from

Athens.

Yanis Varoufakis, welcome to the program.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS, FORMER GREEK FINANCE MINISTER: Thank you, Christiane, to be on it.

AMANPOUR: So, you know, I brought up 2015 and it seemed that you couldn’t go a day without hearing about Brexit and a potential Greek default and

chaos in your land and across Europe and reverberating all over the world. And here we are nearly four years later, Brexit It is in chaos but it’s

happening, these populists and extreme waves of nationalism that you were talking about back then seemed to be the order of the day way beyond

Greece. I mean, you were pretty prescient back then.

VAROUFAKIS: Well, Christiane, in 2008, we — our generation experienced our version of 1929. It began a Wall Street just like in 1929. And very

soon, the world cease to make sense in terms of works was conventional wisdom up until very recently.

We — well, our regimes, are liberal establishment, to put it this way, just like the Weimar Republic in the 1920s, pretended that business could

continue as usual. Of course, the major fault (ph) lines in finance made it that essential in order to pretend that business could continue as

usual, to shift the pain, loss, debt onto the shoulders of the weakest of citizens, especially the United — in the European Union but also in the

United States.

And very soon you had discontent. And that discontent begot political monsters, both in Europe and in the United States.

AMANPOUR: So, political monsters, some — you know, people would potentially describe the extreme right and the extreme left as being this

sort of political monsters, if you like, at least they’re gobbling up any sense of a centrist future, any sense that you can even find a majority for

anything and a consensus to make policy.

So, you have described the threat from this nationalism and this populism and you are launching DiEM25, which you hope to be a progressive

international, a progressive wave to counter this mostly extreme right nationalism. Can you explain how you plan to do that and what is DiEM25?

VAROUFAKIS: Well, DiEM25 is an acronym for the Democracy in Europe Movement but we are also using, you know, the Exultation Carpe Diem seize

the day because we need to seize the day.

As you can see in Europe, we have a domino effect or take orders or fire (ph) polities by extremists of their (INAUDIBLE) who are exploiting the

discontent of the anger in order to turn against one proud nation against another, turn Italians against the Roma against migrants and so on. So, we

need to seize the day.

But allow me just to put it very simply. What we are trying to do is to take one brilliant idea from Franklin Roosevelt’s administration in 1973

from that new deal. And that simple idea is to utilize, to find smart ways of utilizing existing idle cash, idle money, savings that are not being

invested into productive useful things for humanity into the good quality jobs that can uniquely quell the discontent caused by the fact that most

people can see that their children are not going to have as good a life as they did.

And press this idle cash into service in order for green transition, green technologies to green energy, green transport systems. That basic idea

which, in a sense, allow the United States in 1973 onwards to avoid the decline of Europe, the degeneration of Europe at the same time into a kind

of fascist equilibrium, that is that an idea that we want to salvage from the period, to bring it to Europe and indeed, to internationalize if we can

so as to counter an internationalist level, both the failures of a globalization divorce, if you want, establishment that caused the crisis of

2008 and the political representation of the extremists who are now are taking over one company after the other.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, let’s take one country after the other. Let’s start with France where we’ve seen the most violent manifestation of this

discontent. And you have what many in the liberal democratic sort of moderate kind of center saw as a beacon of hope, the election of President

Macron who defeated precisely the voice of nationalism and extremism Marine Le Pen on the right and Melenchon on the left.

And now, we’ve had these massive and violent protests and we simply don’t know even whether the president is, you know, backsliding, is going to

placate them. What is it that — first of all, do you agree with this demonstration of discontent and what will it take? Because they want

something that sounds very counter positional, they want more social services, more help from the state and less taxes. How does this

progressive wave that you envision work in the face of these demands?

VAROUFAKIS: Well, I think it is important to answer that question using what the President Macron has himself said, not very recently but before he

was — before he moved to the Elize when he was still a candidate.

I remember Emmanuel Macron very vividly saying that there have to be reforms in France but at the very same time, unless we have a federalist

reform of the eurozone, of the way the European Union is conducting its business, unless there is a common budget, a federal treasury of sorts in

Europe, unless we have a proper banking union so that we end to this pretense that we can have national banking systems without treasuries that

can actually do that which the U.S. Treasury is doing in salvaging them.

He himself, President Macron, predicted that without these moves towards federalism, towards that kind of serious eurozone reform the center cannot

hold. And the European Union, he said, would be dismantled, that was Emmanuel Macron. He gets elected and he puts forward an agenda for

eurozone reforms, which was a moderate and quite sensible. But the way in which he tried to carry out was a two- phase negotiation with Berlin.

Phase one, he would Germanized France, especially with the labor market (ph) and the national budget and then go to Mrs. Merkel and say, “OK. Now,

I’ve Germanized France, let’s have a federal eurozone.” That failed, it was a colossal miscalculation on his part because he Germanized France, he

introduced prosperity to the national budget, he made it easier for employers to fire workers, he increased taxes for the poor and reduce them

for the rich. And then, when he put forward the proposals for reforming the eurozone, which for him were absolutely essential necessary

prerequisites, Mrs. Merkel said mine (ph). And very soon after that she lost power.

So, the explanation lies in the narrative of President Macron himself. The center is not holding because we are not consolidating the European Union’s

economy the way that — even Mr. Macron who is much more moderate than I am in his politics, had specified as absolutely necessary (INAUDIBLE).

AMANPOUR: OK. So, let me put the little devil’s advocate then to you because some economists do believe that some of the reforms he did put

forth have actually produced results, the labor reforms and others. And the question here is that some also saw, not of galloping French economy,

but a move towards the French economy doing a little bit better and predictions that it would continue to do better if the reforms continue.

The same in Germany, a still galloping economy. In Britain, the economy doing really, really well. In the United States, the economy is doing

actually really, really well. And yet, this Malez (ph) and yet this rebellion against the governments whose economies are doing well for them.

So, if this is the result when the economies are going well, what happens when they go really badly, if that seems to be the — if that — if you

predict that to be potentially the case down the line?

VAROUFAKIS: Well, I think the key to understanding what’s going on and answering your question is to look at these economists and manage to

discern the fact that they’re not uniform. You talked about Germany. Germany is indeed swimming in cash, it is swimming in surpluses, everybody

seems to be having surpluses. The federal government is in surplus, there is a majestic, gigantic trade surplus that Donald Trump is targeting, there

is — there are corporations that are saving money and there are households that have savings.

And yet, Christiane, and yet — and this is the great paradox which I think answers your question, half of the German population are far worse off

today than they were 50 years ago. Similarly, you spoke about France and their reforms. Yes, it is true that Macron made business easier to conduct

in France. But at the same time, he introduced austerity which was effectively exported from countries like Greece into France, and that

created all the regions in France that resemble Greece. In other words, areas of a great depression. And it is in those areas that the movement of

the gilets jaunes, the yellow vests emerged before descending upon the streets of Paris.

You mentioned the United Kingdom. Well, why did Brexit succeed? It did not succeed because of some deep antipathy towards the E.U. It succeeded

because a very large percentage of the population were being treated or felt that they were being treated like cattle that had lost their market

value, they felt discarded, they felt completely disenfranchised from a London based economy which was, as you said, expanding very rapidly while

large sections of the population and of the country were being left or held behind.

This is the issue here, division within our countries and between our countries growing while statistics at the macro level seeming to be

prospering. So, you have effectively national statistics about prospering and large proportions of the population that are being discarded.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, now, let me put this notion of division and nationalism and populism to you in this context. Steve Bannon, President Trump’s

election campaign genius wiz who helped him win the election has as, you know, been in Europe, trying to round out all these extreme right

nationalist parties and elements into what he called “The Movement” to contest, most particularly, the upcoming European elections in May of next

year. This is what he says about his movement.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

STEVE BANNON, FORMER WHITE HOUSE CHIEF STRATEGIST: The beating heart of the globalist project in Brussels. If I drive a stake through the vampire,

the whole thing will start to dissipate. We’ll call it “The Movement” or the “The Cause” or something like that. Everything converges on May of

2019 and that’s literally when we take over the E.U.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: That is pretty frank and rather chilling talk actually from a guy who’s got a proven track record of getting a president elected with

some of those views. Are you concerned or do you see your movement as going up directly against his movement?

VAROUFAKIS: Listening to Steve Bannon sends shiver down my spine. Because while nobody can accuse me of being uncritical towards Brussels and the

European Union, this disintegration nationalist narrative is what is going to lead to a great deal of pain being inflicted upon a majority of people

in a majority of countries in Europe. This coalescence of nationalists is working towards disintegrating the European Union in a way that will only

bring into power strong men like Mr. Salvini in Italy, like Mr. Scurtz (ph) in Austria, Mrs. Le Pen in France, the result being a dystopia, the result

being a genuine post-modern version of the 1930 S.

And yes, DiEm25 or Democracy in Europe Movement, while being very critical of the European establishment, we’re going to fight Mr. Steve Bannon on —

in every rail with upon European humanist narrative, one that seeks to bring together the peoples of Europe not to divide them and to disintegrate

them.

AMANPOUR: So, I wonder whether you think that you will succeed, whether you are optimistic about the challenge you have at hand. And particularly,

I want to ask you about one of the biggest rallying calls and cries to these nationalists is the issue of immigration. And, you know, the

Hungarian foreign minister talked to me about this. I mean, they just do not want practically anybody except for White Christians to come in. And

you know the U.N. migration charter pretty much failed in Marrakesh with all the relevant countries sort of pulling out and refusing to sign on and

the United States not even sitting at the table.

Listen to what the Hungarian foreign minister said about this central issue to me when we spoke in September.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PETER SZIJARTO, HUNGARIAN FOREIGN MINISTER: My question is, what is the legal or a moral ground for anyone to cross, to violate a late border

between two peaceful countries? These people came through Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, all peaceful and safe countries. So,

it’s not a fundamental human right that you wake up in the morning, you pick a country where you would like to live in, like Germany or Sweden, and

in order to get there you violate series of borders. This is not the way it should work out.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, I mean, there’s a lot to question there. But nonetheless, you get his point. What does your movement seek to do to address the fear

and loathing around migration today?

VAROUFAKIS: Well, isn’t it interesting. You will recall the Hungary was a communist country and lots of Hungarian Democrats fled the country and

sought refuge by crossing borders, they’ve — they sought refuge in Europe. And indeed, when the regime collapsed, we opened up our borders to

Hungarians, to the Czechs, to the Slovaks and so on.

That is the fundamental basis of a democratic Europe. That we feel is stronger when we bring border fences down, not when we are acting (ph).

AMANPOUR: Right.

VAROUFAKIS: Europe does not have a problem with migration. Europe has a problem with austerity, with a failed economy, with a failed economic

system. And let me remind you, something else which I think is of interest, Hungary has no refugees. Hungary has very few migrants.

In my country, which is already suffering a monumental economic collapse, we have tens and hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants. You do

not have an antiimmigration feeling in this country.

But you asked me whether I am optimistic. Christiane, I do believe very strongly the when it comes to politics, when it comes to fighting for

democratic rights and for humanism, we don’t have the right to issue predictions. We have a moral right to do what is right and then simply to

expect that hope is going to be the fuel that drives the success in the end.

AMANPOUR: We will be watching. Yanis Varoufakis, thank you so much for joining us from Athens.

So, as we were discussing centrist politics are kind of out of vogue, of course, in the fashion world it rarely pays to stand in a crowd when it

comes to the environment and climate. However, some of the world’s biggest fashion houses are finally gathering under one roof. Dozens of leading

brands and designers have signed a charter which was unveiled at the United Nations COP24 climate conference in Poland this week. Aimed at fighting

climate change and curbing greenhouse gases by the fashion industry, which is among the world’s biggest polluters.

At the forefront of this movement is Stella McCartney, the highly respected British designer who’s following in the footsteps of her parents Paul and

Linda McCartney who are both animal rights activists. She has forged her own cutting-edge brand of sustainable fashion.

Stella who has been designing standout pieces since she was 11 told me about the ambitious new targets when she came to the studio this week right

after taking part in a Bloomberg climate event here in London.

Stella McCartney, welcome to the program.

STELLA MCCARTNEY, FASHION DESIGNER: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: So, I never knew that the fashion industry was the second biggest polluter in the world. I mean, how does that happen? Walk us

through how polluting your business is?

MCCARTNEY: Oh, my goodness. Well, basically, it starts at the very beginning. So, the sourcing of all the materials and the supply chain, the

manufacturing is just filled with really sort of old-fashioned manufacturing skills. This close realm (ph) is basically comes from

forests, from ancient, forest cutting down trees, a hundred of million were cut down last year, a 150 million will be cut down this year. Plastics,

the oil that is used in so many fabrics, the chemicals that is used, you know, leather is cutting down forests, it’s using water inefficiently.

I mean, at the end of the day, there is very little connection between all of the sort of dots.

AMANPOUR: Let me read a few of the statistics that you mention and then we’ll talk about the solution. So, in terms of plastics, the Ellen

MacArthur Foundation report says, “One garbage truck of textiles is wasted every second, less than 1 percent of clothing is recycled into new clothes.

And of course, if nothing is changed, the industry will consume about a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050.”

And then Kashmir takes so much environmental damage, cotton, as you mentioned, cost so much environmental damage. So, what can you do to

change that dynamic and what are you doing? Because you are the leader in this part of the sustainable development.

MCCARTNEY: You know, if I can do it, anyone can do it. You have to ask questions and you have to start that very starting point of basically

agricultural farming. You know, cotton is one of the materials that I use the most but I use organic cotton. I look at regenerative farming in

agriculture.

So, I’m looking at the soil. One — basically, the soil holds twice as much carbon in it as there is in the atmosphere. So, if we release that,

we are screwed. So, I don’t want to do that. So, I look at different ways of putting nutrients back into the soil. I’m very mindful of how I treat

my fellow creatures.

You know, the reality is, is when I — I don’t use any leather or any fur, I don’t use any animal glues or any chemicals that are involved in that,

and that has the biggest positive impact personally in my business on the environment.

And, you know, it’s basically connecting all of the dots, working together, circular economy when you talk about fast fashion and the landfill every

second or it’s in exonerated or it’s landfilled essentially. We can’t actually accommodate that anymore. It’s not a sustainable business model.

Over 500 billion worth of waste is being, you know, lost. And that is, for me, a business opportunity.

AMANPOUR: Let’s unpick some of that, the landfill. You showcased your latest collection, right. I think is in 2017, that collection, in fact.

In a landfill to highlight the issue. What were you saying, what did you hope the impact would be?

MCCARTNEY: I wanted to sort of try and keep it light at the same time. I think it’s really important that Stella McCartney to have the tone of voice

that doesn’t completely terrify everybody, try and keep a sense of humor, trying to keep a sense of hope. So, I shot in the landfill and it seemed

like a sort of great idea at the time and then I actually had to go — I had to find a landfill actually in the first place that would let me shoot

in it. There was only one, it was in Scotland, sadly for Scotland.

But, you know, it’s not an industry that people have to keep proud of or that they actually want to show. I think that kind of, you know, contrast

between fashion and the lack of glamour that there is in the landfill was of interest to me. We — the massive part of the shoot was on — it was a

dust bowl speaking of soil, speaking of just over farming and just raping the soil of its nutrients, which is what we do. You had to wear masks, it

stank, it was just horrific, it was really horrific to be there.

AMANPOUR: So, it’s a real landfill, smelly and oozing and gross.

MCCARTNEY: I was like, “This is not what I signed up for when I wanted to be a fashion designer.” And then we had one area where we did clean

rubbish, clean waste, which is apparently the recycling. Now, only 2 percent of plastics are recycled, 1 percent of fashion, as you say.

So, it was ery small area actually on the shoot, which was really disappointing because you think wouldn’t — you know, we’re kind of led to

believe that we are recycling especially in the culture like Great Britain but that the statistics are really, really tiny and, you know, we have to

make change.

AMANPOUR: Did you ever think that your world, your life would be as much designing as being a science lab? I mean, you’ve recreated your entire

store and you’re constantly looking at tech innovation and material innovation.

MCCARTNEY: Yes. No, I thought that it would be much more sort of glamorous and kind of, you know, creative. But, you know, I still —

luckily, I have that side and it drives me. But the other thing that really inspires me is the future of fashion, looking at all of these

problems that we face and what we contribute negatively to the environment and using technology is a solution. So, I went with tons of new

environmental technologies looking at growing leather in laboratories, looking — I work with a company in San Francisco that grown — we’re

basically making spider silk in labs. I have clean air in my store in London where its 98 percent filtered and its sort of amazing.

And just looking at technology for the future of fashion for me, I find really sexy. And trying to make it — China make sustainability something

that you’re not sacrificing in order to be fashionable. I think that educating people is critical, trying to have a kind of positive tone but

also giving people information because the consumer really counts.

AMANPOUR: You know, you come at it with such passion but also, it’s in your DNA. It’s very, very well-known that you were the daughter of Paul

McCartney and Linda McCartney. And she was the pioneer, almost vegetarianism and animal cruelty to the public conscious, fighting against

that. What was it like being her daughter, living and growing up with that? And also, actually, what she would be a little bit ridiculed and

attacked for those positions all those years ago?

MCCARTNEY: Yes, yes. We know it’s never easy. It doesn’t matter who your parents are, you want to protect them and you want them to feel safe and

you know. Yes, she definitely got a lot of ridicule, a lot of sort of anger and — you know, pointed at her because of her belief system and

trying to save animals lives essentially really and educate people. You know, and (INAUDIBLE) there was a veggie sausage or a veggie burger in this

country until she came along. And that was really born out of her desire to save animals lives.

I think that brought me in awareness and the consciousness, it made me see the you can be fearless and you can make change if you believe it and you

have a passion, you know. And we really believe in this, in our family. It’s something that we’re massively committed to.

And it’s funny, you know, I’ve seen the same things in me, I’ve been ridiculed for the majority of my career as a fashion designer, in luxury

and not use leather and not use fur and sort of challenge the future of fashion in the way in which we work in an unsustainable way. I mean, I’m

kind of the freak of the fashion industry.

But, you know, now, I think it’s — I can have this conversation. So, I see change. I’m incredibly proud of everything that mom did and how she

inspired me to do what I do and my dad.

AMANPOUR: Did he get it from her or was he inclined?

MCCARTNEY: I think they were — I — you know, I’d like to think it was a group effort.

AMANPOUR: You are not a freak, you are actually on the cutting-edge. You might know that L.A., the whole city of L.A. has just banned the sale of

new fur, Gucci, Burberry, Versace, Calvin Klein, Armani also going fur free.

MCCARTNEY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So, you are actually having a major impact but also so are people on the street, young people, they are really, really concerned. You

know, you also say that you were kind of ridiculed at the very beginning. Again, how — you were at first known as Paul McCartney’s daughter. How

difficult was it to forge your own way and your own platform and your own cutting-edge view of design and materials?

MCCARTNEY: Well, you know, it wasn’t easy. Every interview I started out doing was sort of like with a little help from her friends and it was all

sort of Beatle headline driven. And I had to kind of justify my place within the industry. I had to prove that I had a validity and that makes

sense. You know I get it but I trained to be a fashion designer. I did sort of the similar training that every other fashion designer I know did.

I went to Saint Martin’s and, you know, it’s something I — you know, I was interning at 15. It’s my passion. I was very committed.

But I think that at the end of the day, my grandfather used to say stay in power. And so first it was, I was Paul and Nancy’s daughter, then I was

the sustainable kind of weirdo. And now, I think that — I think creativity is at the core of everything. I don’t think I’d be sitting here

talking to you if my product was rubbish. It would just be landfill too if I was sitting here making humbugs, you know, handbags. Sorry. Humbugs?

It’s OK like it works.

AMANPOUR: It works.

MCCARTNEY: But I think at the end of the day, you have to have sort of — now, I have a great team of people and I think that we create beautiful

desirable products. And I don’t think I can even open a conversation with someone like you on this type of platform unless I have something at the

core of it and create in a creative way.

AMANPOUR: And you say you studied at the correct schools, you interned, you worked for Christian Lacroix in Paris as an intern. And then you took

over Chloe at a very very young age from the great Karl Lagerfeld who, it must be said was not entirely supportive. This is what he said, “Chloe

should have taken a big name. They did but in music, not in fashion. Let us hope she’s as gifted as her father.” Wow. That’s a little sexist —

MCCARTNEY: How great.

AMANPOUR: — a little misogynistic, a little nepotistic.

MCCARTNEY: You know what, it’s kind of hilarious too.

AMANPOUR: But you sort of proved him wrong. I mean how much of you increase the profit? Did you increase the profit at Chloe?

MCCARTNEY: At least 600 percent in a very short period of time. But you know what, I’m very happy to be here listening to that quote. I feel like

just being here and you reading out to me maybe proves it wrong.

AMANPOUR: Well, bigger. And again, you were 11-years-old. This is all part of the Stella McCartney fashion — sustainable fashion legend. You’re

11-years-old when you made your first design and it was a pink faux suede bomber jacket. At 11, what did you know about faux suede?

MCCARTNEY: Yes. Well, you know, I just knew — when I found it really interesting because basically most upholstery is made from faux suede. You

can wash them. You can throw it in the washing machine. So things like that I found really interesting even then, sort of technical side.

I now work with obviously faux suedes overtime that are biodegradable. And that’s sort of what I do when you talk about me being more of a scientist.

Every single day, I’m questioning this sort of same 10 materials that the fashion industry has been using for hundreds of years. I’m challenging it.

And I think that’s part of the creative process now for me.

AMANPOUR: What about women? You say that you don’t only create for women and you’re constantly looking to make them beautiful and professional and

also affordable. But you also — don’t you have a massive percentage of your employees are women?

MCCARTNEY: I think it’s something like over 80 percent. Yes. Not intentionally. I mean I just think — I don’t know. We kind of joke that

the man — where are the men in Stella McCartney?

AMANPOUR: Do you ever worry with all this mayhem? I don’t want to get too political but Brexit might affect your very particular supply chain.

Because again, you talked about rayon for the Americans. You have sustainable forests in Sweden. There are malts in Germany. The thread is

made in Italy. Some of your clothes are made in Hungary. Are you worried about the supply lines?

MCCARTNEY: Well, I mean it’s certainly a topic of conversation that we’re looking at. We’re a very global company. I mean on a very base level,

those over 80 percent of women employees are from all around the world. So yes, we have to safeguard and look at all of the implications from Brexit.

AMANPOUR: And finally, one of the things we haven’t really talked about and I think you think it’s for the next wave of discussion is to focus on

the animal cruelty aspect of being a vegetarian, of not using real leather, et cetera. And I just go back to what your mother said, “If

slaughterhouses had glass walls, everyone would be a vegetarian.”

MCCARTNEY: How ahead of her time was she.

AMANPOUR: She really was.

MCCARTNEY: I talk about that now because there’s a lot of challenges. There’s a lot of bodies that have a lot of power, and money, and financing

behind in the fur industry for example. And they can challenge a faux fur and they can say it’s more natural to have a fur. If it was more natural

fur, would just biodegrade. Obviously, there’s tons of chemicals involved in that process that prevent that from happening.

But the reality is that the core of that is animal welfare and the mass slaughter of billions of animals in the name of fashion every year. And I

don’t know where these farms are. I don’t know where they’re making all the leather. Like if it’s such a proud, beautiful, luxurious,

desirable product, then why are we not openly allowed to go in and see how they kill these animals, how they’re grazing, what conditions they’re

living in.

You’re allowed to go in. Has CNN ever been an open —

AMANPOUR: Not that I know of to be honest with you.

MCCARTNEY: — to be greeted by a fur house. So I think those are the questions to next be asked. Because at the end of the day, we are

inhabiting this planet with our fellow creatures and their welfare is important.

AMANPOUR: And at the end of the day, you are a businesswoman. You run a fashion empire and therefore profit, the price point is very important to

your business but also to your consumers. What do you say to people who say, “Well, all of this sustainability is just great but it jacks up the

price”? At Stella McCartney, what do you do with your margins?

MCCARTNEY: We suck it into our margins. But you know, at the core of why I’m doing this, it’s because it’s my core principle and value system. So I

can’t put that on to my consumer and I’ll price myself out of the market so then it becomes a redundant sort of way of working. I’m in a very

privileged position that the core of everything for me if everything goes horribly wrong, I can sort of go home and go, “Oh, can you look after me?”

And I know that and I see that as a privilege. It’s enabled me to sort of not compromise my ethics.

But I think one of the main things to talk about there is I shouldn’t really have it. I shouldn’t be hit for having the right principles in my

business model. I should be incentivized. When I take leather, non- leather products for example into the United States, I can be hit with a 30 percent taxation because it’s not real leather. Now, that sort of got to

be a medieval law that’s still in place. It should be the opposite.

There should be policies now in place to incentivize people in the industry to do better business and just to be less harmful to the planet.

AMANPOUR: On that edge, on that edge — on that note —

MCCARTNEY: It is an edge though. It’s an empty conversation.

AMANPOUR: Well, it actually is a cutting edge is what I meant because it is cutting edge. And you are staking out a position. You talk about the

United States where the current government calls climate change a hoax and doesn’t believe that it’s manmade. So it is actually edgy and quite brave

and economically successful. That is a lesson.

MCCARTNEY: Well, hopefully, it’s the future.

AMANPOUR: Hopefully. Stella McCartney, thank you very much.

MCCARTNEY: Thank you so much for having me.

AMANPOUR: And now we turn to an issue that will be close to many viewers’ hearts. On average, 20 U.S. soldiers are loss to suicide every day. A new

documentary series “The War Within” tells the story of three retired Veterans. Assal Ravandi is an Iranian refugee who came to America when she

was 12. She decided to enlist but after returning from Afghanistan, she struggled with PTSD. And, of course, all these families are affected. Our

Hari Sreenivasan sat down with her and one of the series producers Lauren Knapp.

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: Lauren Knapp, tell me what is The War Within series? What are you trying to accomplish?

LAUREN KNAPP, SENIOR PRODUCER, THE WAR WITHIN: The War Within is focusing on three — the experiences of three different veterans who have all been

coping with PTSD over the past several years. And as a filmmaker, my goal is really twofold.

One, I’m hoping that civilians will watch their stories and understand a little bit more about the lingering effects of war and how it can often

stay with soldiers for the remainder of their lives. And the second is really to reach out to people who might be experiencing PTSD or mental

illness themselves or family members of people with PTSD. So that they can benefit from hearing Assal, and Scott, and Dave on stories.

SREENIVASAN: Assal Ravandi, you are one of the people that she profiles. For our audience, tell us a little bit about your background.

ASSAL RAVANDI, U.S. ARMY VETERAN: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me. I’m an Iranian-American. We moved here with my mother and my brother

in 1993. My father immigrated to United States prior to us moving here. However, he was killed in a plane crash about a few months before we

arrived so it was just me, my mom, and my brother. We’ve kind of started over after.

My father was a political activist in Iran against the Islamic regime and he was a political prisoner for a while and so we found ourselves all alone

for the most part of my childhood. And my mom raised us as much as she could and took care of us with the family.

SREENIVASAN: What made you want to join the army?

RAVANDI: You sort of become — as an immigrant, I feel like you sort of become an idealist when — it just depends on how America was presented to

you when you first arrived. And America was presented to me as, you know, exactly what it truly is, a land of opportunity, a land of the free. And I

was so moved by the 2008 election and I sort of became obsessed with the idea of working for President Obama.

I admired him. I looked at him and I wanted to be just like him. And I — whenever I looked at him on television or listen to his

speeches, I felt like he represented the best of America and that is what I believed at the time and started campaigning for him. And then after the

election, once the economy crashed, instead of taking a break from the entertainment industry, I felt that this would be a perfect time to serve.

And in my own little bubble, idealistic bubble, I wanted to say that I worked for Barack Obama one day.

SREENIVASAN: Through the military?

RAVANDI: Through the military. He was the commander in chief so.

SREENIVASAN: Right. You were a green card holder at the time, you’re not a citizen, and you volunteered. What role did you play?

RAVANDI: I went in as a logistical specialist. And once I obtained my citizenship, they cross-trained me four months later to become an

intelligence analyst and where I utilized my language skills to teach Farsi to infantry soldiers and officers. And when I was down range, I was able

to use my skills as well.

SREENIVASAN: In addition to assault story, you also have the stories of two other veterans. I want to take a look at a clip from Davon Goodwin.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAVON GOODWIN, VETERAN: August 31, 2010, my vehicle hit an IED and that led to having a fracture in my lower back and a traumatic brain injury. I

was diagnosed with narcolepsy and the PTSD.

The bomb goes off every single day. The Davon that it took, I will never get that person back. I didn’t do it to be a better American. I’ve done

it because I didn’t want to be in debt over my head once I graduated from college.

Met a recruiter and he’s like, “Well, they’re giving all this money. I mean, they got student loan forgiveness, they got Montgomery GI Bill. I’m

going to put you in a non-deployable unit. You’re going to be fine.” I’m thinking, hell, it’s a win-win. What’s the worst that can happen? And

boy, did I know that’s not how the Army works.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Lauren, one of the episodes, he talks about how there’s “only so much rage you can bottle up.” How does this play out in his real life

with his family, with his child?

KNAPP: Yes. So when Davon came back from Afghanistan, he was dealing with the aftermath of a traumatic brain injury and part of that manifested as —

in narcolepsy which he still has today. He had headaches. And then with the PTSD, he experiences very extreme anger. One of his triggers was the

sound of crying.

And a few months after he came back from Afghanistan, he had a baby. And so that was —

SREENIVASAN: A little bit of crying involved.

KNAPP: A little bit of crying of baby. So that was a difficult period for him and for his girlfriend and for them as a family. He eventually was

able to finish college and moved out to the farm that we just saw in the clip. And he found a lot of therapy and solace in that farm and in that

space where he could feel safe, he could feel like he could control his environment which is really important. And he is, you know, still with his

girlfriend. He’s now kind of becoming the father that he always wanted to be. And he says he’s making up for lost time but it’s really amazing to

see them as a family unit connecting and his son is 7-years-old now.

SREENIVASAN: Assal, I want to hear a little bit about the kinds of stresses that you experience when you’ve got to Afghanistan versus what you

prepared for when you actually got there and you were in the theater. What was it like?

RAVANDI: Well, prior to my leaving to Afghanistan, we were told that this particular mission, this nine months of deployment is not going to involve

leaving the wire. And knowing —

SREENIVASAN: Meaning being in a compound, not being out?

RAVANDI: Not being out. My boss is very open-minded. He was an excellent intelligence officer and I told him knowing fact that I am a neutral

gender, I can speak to women and men and I don’t need an interpreter and I’m armed. They’re going to have me run missions so we need to just

prepare for this. Physically, mentally, we were ready. But I think there was this little emotional aspect of it that I think there is a mental

readiness, physical readiness, and there’s an emotional readiness.

And, of course, as a soldier, you’re mentally and physically tough but when they keep telling you, “You’re not going to do something,” you start

believing it. We hit the ground running immediately. I mean we started just working with the unit that was leaving. And so when I found out that

we are going to be going outside the wire, especially there was that high demand for my skill.

SREENIVASAN: So what happened the first time you were under attack?

RAVANDI: We were attacked every day. And the first time was the second day that arrived in Afghanistan. And this is something that most people

don’t acknowledge. Indirect fire is one of the most traumatizing events in theater. And although I ran 85 missions in 275 days outside of

my compound but inside the compound, you are constantly under attack.

SREENIVASAN: So what happens to your brain when you’re in a situation where you hear the sound of it coming but you don’t really know where it’s

going to hit?

RAVANDI: I think the first time I was able to utilize my training, you know, hit the ground, do all the — what you need to do. But after the

second or third time, you start thinking today’s the day, today’s the day that I’m going to die in Afghanistan. And after a couple of weeks, when

you start learning that somebody’s throat got cut by shrapnel on flight line or a pilot had a rocket land on his chest the day before he was taking

his first flight and the day after he had arrived from United States, after that he was indirect fires or no longer indirect in your mind. I think

they have a tendency to inject a sense of trauma and it’s daily and it’s more than once a day. Sometimes, we were rocketed 5 to 12 times.

SREENIVASAN: Lauren, are you seeing any commonalities in how these three different people, they had very different experiences but how are their

brains different? I mean if you lived through something like this or an IED blast or some of the other things that they describe in your

documentaries or — is there some sort of change that’s happened to them that would be visible to civilians?

KNAPP: We talk a lot about invisible wounds with this series. And that’s actually the challenge for me as a filmmaker, to film something that we

can’t see and that’s one of the contributions to the stigma surrounding mental illness is that you can’t see it. And so it manifests in different

ways and that depends on the complex personalities of each of the individuals.

With Davon, it manifested in anger and extreme irritability. I’ll let Assal speak for herself. With Scott, it’s depression.

SREENIVASAN: So I want to ask, I mean what did you expect when you were coming back home? And compare that to what actually happened.

RAVANDI: I think our experience kind of splits in three sections. First, you don’t want to be there and you start getting comfortable. And then by

the time it’s time to come home, you don’t want to. And so when I was coming back, I was already nostalgic about my environment. And I remember

my boss telling me no matter what you do for the rest of your life will never compare to what you did here, the contributions you made.

So when I was coming back, I was already sad. When we were in Romania, we — I was happy that I was coming home but I was starting to feel depressed.

However, that sense of vigilance that you maintained throughout deployment is still with you so it doesn’t manifest the depression and anxiety,

doesn’t manifest itself until you get back stateside. And once I got here, I don’t even think it took more than a week because my mom and my brother

came to visit me about 11 days after I arrived. And their two weeks’ visit turned into three days.

SREENIVASAN: Why?

RAVANDI: They just couldn’t be around me. I couldn’t function like a normal person.

SREENIVASAN: What do you mean?

RAVANDI: We went to a restaurant and I wanted to eat and leave. And we couldn’t even stay and have a good time because I just wanted to eat the

food and leave. There was no — I had no sense of purpose and I wanted to just rush through the day so that became an issue.

I was bothered by every sound, every — I remember my brother was playing something that was so beautiful Rumi which — he is a poet and a

philosopher, a Persian philosopher but the language bothered me so much. I immediately thought it was Arabic and immediately it just kind of — I came

downstairs and started screaming that I just came back from Afghanistan and I don’t need to hear this in my house and three days later they were gone.

SREENIVASAN: This seems not just anti-social but almost in a way, she’s putting herself in a place where people can’t reach her, people who love

her can’t reach her. And you kind of see this in the other characters that you’re following too.

KNAPP: Yes, absolutely. Isolation is a big side effect of PTSD. There’s a real tendency to shut people out. And unfortunately, that is — that

kind of creates a negative feedback loop and that can exacerbate the other symptoms. And one of the things that is definitely common

between Assal, Davon, and Scott is that they’ve all gone through these periods of isolation and you’ve all come out and reengaged with communities

in different ways.

RAVANDI: Absolutely.

SREENIVASAN: Tell me what was the point — the turning point? What was rock bottom for you?

RAVANDI: One day I noticed that I was just drinking every day from 11:00. That’s when I think my mom noticed there was something seriously wrong with

me. So she came to Washington D.C. from San Antonio and I made our differences of opinion and excuse to separate our accommodations so I got

her an apartment so like it shut — like put her out.

SREENIVASAN: Just physically put her at a distance?

RAVANDI: Exactly. So — and I said I’ll support you, I’ll take care of you but I wanted to be home alone so I can drink and be depressed. And I

didn’t want anyone to tell me, “What’s wrong with you?” I didn’t want anyone to get in my way of falling into this rabbit hole.

And I remember the day before I hit rock bottom, she came by to see me and she knocked on the door. She said, “I’ve been calling you. You’re not

answering your phone.” And I said mom, can you just leave? Sorry. I’m sorry.

SREENIVASAN: It’s OK. What made you realize that this was not the right path, that there was something better?

RAVANDI: So the next day was one of the worst days. I remember I had a bottle of Honey Jack Daniels. It was a whole bottle. And I started

drinking around 10:00 a.m. and by, I think sometime around two or three in the afternoon, I had already blacked out.

SREENIVASAN: Have you ever thought of taking your own life?

RAVANDI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: Were you ashamed of feeling this way?

RAVANDI: I was.

SREENIVASAN: Why?

RAVANDI: Because I couldn’t build new relationships. And you couldn’t — you can’t go walk up to someone and say, “By the way, I just want you to

know that I have post-traumatic stress and I could lash out any second. And I just want you to know that it’s OK. I will be fine in two minutes.”

And — but you can tell someone that you know I have cancer and I’m going to do chemo next week for the entirety of the week and I’ll be weak and

I’ll throw up at the end of the day.

SREENIVASAN: And they’ll accept you for that.

RAVANDI: And they’ll accept you for that but they won’t accept you for this person who is — something triggers with every inconsistency. Like

inconsistency is one of my triggers. So if you are late to a date, I’m already sick. So I figured there’s something seriously wrong with me.

And that day that everything just kind of went black, I felt most ashamed. And when my mom came to the hospital, I promised myself that that day was

never going to define me. And I’ve been hiding that story for so long until Lauren came to me and wanted to tell the story. And through the

trust we’ve built, I was able to share my story.

SREENIVASAN: Lauren, do you find this with the other characters that there’s a significant reluctance even to get into this because maybe we

wouldn’t understand or we wouldn’t accept them?

KNAPP: They each told me in different ways that in sharing their story now through this series, it’s giving the pain that they’ve experienced meaning.

It’s hopefully reaching another veteran, another individual who might be in a very dark place who might need to see that there is hope. It’s giving

them that sense of hope and that is their — everyone’s motivation as they’ve told me to participate and I think that that’s incredibly admirable

because they are sharing some very intimate and difficult things.

SREENIVASAN: You know you built an organization kind of out of the ashes of this. Tell us a little bit about that and why you did this.

RAVANDI: So AUSV was — Academy of United States Veterans was created to one — it was an excuse for me to bring all the vets together. I just kind

of wanted to be around all of them. That’s how it started. Their mission was let’s do some — let’s throw a party for me and get everybody to come

to see me. But then, when they arrived, they were all happy to see each other and that we all felt the same. It was about 600 of us the first time

veteran supporters, family members at the George Washington University.

SREENIVASAN: You have an annual awards ceremony every year?

RAVANDI: Yes, yes.

SREENIVASAN: And what do you honor?

RAVANDI: We honor organizations and programs for profit and nonprofit that work towards the wellbeing of the veterans’ community on the ground in

different categories.

SREENIVASAN: Lauren, as you look into this, as you research this material, what kind of infrastructure is capable of making sure that we can intercept

these trips to these places of rock bottom, that we can stop that from happening in the first place?

KNAPP: I think a big key is awareness. What Assal is doing, and Scott and Davon is sharing their stories and hopefully normalizing mental illness and

PTSD, building community, and incorporating civilians into that space.

SREENIVASAN: What should a civilian know? How should we act? What can we do?

RAVANDI: There is not one or two things that I want the civilian community to know. But I can tell you this, over the past four years that I have

been able to co-exist with others who have not served, I have found it easier to be able to interact with the veterans’ community, our dark sense

of humor, and some of our ways of just kind of conducting ourselves just makes it easier.

But there is another way to be able to reach one another, whether it’s us reaching our civilian loved ones or the other way around. And I honestly

think the only solution for any mental health problem is love. And I know it’s cliche but it’s really true because that’s what healed me.

SREENIVASAN: Senior producer Lauren Knapp, Veteran Assal Ravandi, thank you both for joining us. The series is called The War Within. It’s

available on Facebook now.

KNAPP: Thanks so much for having us.

RAVANDI: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Love, it is a sobering reminder of a human toll and the struggles of transitioning from frontline to civilian life.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END