Read Full Transcript EXPAND

|

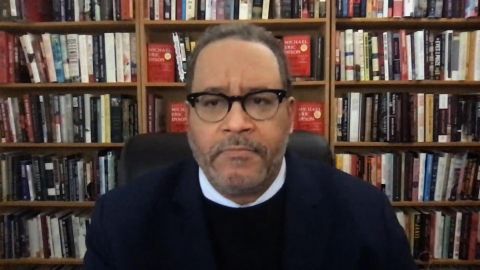

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up. (BEGIN VIDEOTAPE) DR. MONCEF SLAOUI, CHIEF ADVISER, OPERATION WARP SPEED: I will be the first, as soon as I’m authorized, who will take the vaccine and give it to my family, absolutely. AMANPOUR (voice-over): Our Walter Isaacson talks to Dr. Moncef Slaoui, the chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed. Then: JOE BIDEN (D), PRESIDENT-ELECT: We also have to make sure that, when the vaccine is distributed, it’s accessible to people who have been hurt the most, the brown and black communities. AMANPOUR: A pandemic, a presidential election, and historic protests have seen racial inequality come to the fore in 2020. Author and minister Michael Eric Dyson tells me it’s been a long time coming. A celebration, as Yusuf Cat Stevens rereleases two masterpiece albums on their 50th anniversary. (END VIDEOTAPE) AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London. As the delivery of COVID vaccines now gathers pace here, around the world and in the United States, discussions abound about who should get those precious first doses. Mostly care home residents and staff and the elderly will be at the front of the line. But, in their first joint interview, president-elect Joe Biden and his vice president, Kamala Harris, emphasized that vulnerable black and brown communities need rapid access as well to this vaccine. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) BIDEN: Folks who are African-Americans and Latinos are the first ones hurt when something happens, the last ones to recover. And you saw the statistics. You know, they’re somewhere, depending on which report you get and where you’re talking about, from four to five times more likely — three to four times more likely to die if they get COVID. So, they need the help, and they need to get it in immediately. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: And, all week, we have been updating you on the grim records the United States has been setting in deaths, hospitalizations, and now surpassing 14 million cases. Dr. Moncef Slaoui is the chief scientist in charge to Operation Warp Speed, which is the federal program that helped get the vaccine to the United States market in record time. And here he is talking to our Walter Isaacson about the key issue, safety. (BEGIN VIDEOTAPE) WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And, Dr. Slaoui, thank you for coming on the show, and thank you for all you have been doing. SLAOUI: Thank you for having me. ISAACSON: We have been slammed in the past few weeks with another surge of coronavirus, a person dying every minute. So, tell us. Next week, next Wednesday, when the FDA committee meets and the Wednesday after that, do you think we’re going to get the Pfizer and then the Moderna vaccines? SLAOUI: Well, listen, I hope we will have the approvals very quickly after the meeting. However, it’s important to note that the FDA process is totally independent from the operation. And we did that by design to make sure that the independent regulatory body functions appropriately. I am sure that the review that is being made is very thorough and very deep, and I’m sure they are doing everything possible to reach a quick conclusion. I expect it to be positive. The data, frankly, are remarkable. You know, what’s really powerful is the fact that two vaccines using similar technologies, but acting slightly different, broadly similar technologies, developed independently, tested independently in two large trials, come up with almost identical outcome on many different levels. To me, it’s an enormous reassurance that the data are real, are extremely robust, both on the effects of the vaccine and on the safety. ISAACSON: And it’s particularly interesting because these are vaccines that have never been proven before, which is just sticking messenger RNA in our cells and having our cells produce those spike proteins. That’s never been done before, right? SLAOUI: This indeed has never been done as an approved product. There have been many different clinical trials for different diseases using this technology on a few hundred individuals at a time over the last, I would say, at least four years or five years. But there has never been a product approved. I think now we have experience in 70,000 or so people immunized with this platform technology between the two companies. And, really, the data are very reassuring in terms of the short and midterm safety of this vaccine. And what we know is the short and midterm safety are predictive of the long-term safety. ISAACSON: So, you can tell people, just look right into the camera and say, trust us now, we have tested this, these seem very safe, as safe as any other vaccine? SLAOUI: Here’s what I say. Every single data I have seen on the toxicology and animal work that assess potential harm and biological reason for harm show that there is none, and it’s very similar to other vaccine. All the data I have seen on the safety of the vaccine in the clinical trial shows that the efficacy is outstanding and the safety is similar to that of many other approved vaccines. And there — and all the data I have seen from other vaccine shows that, when safety is clear in the first 60 or 90 days after starting immunization — this is one of the reasons the FDA asked for 60 days after completion of immunization — that data is predictive of long-term safety. And it’s the case here. That is one part of the equation. I think it’s important for us to realize the other part of the equation. Unfortunately, we have more than 2,000 people dying every day, and 100,000 people in hospital. Our life has been turned around. We can’t work. We can’t go to school. Everything is stalled. That’s the risk we know. There is maybe a conceptual risk that one person out of a million may have a problem. It’s impossible to predict. The only way to know it is to do it. And in using the vaccine, we will prevent all the harm I just described that we know. And, therefore, I will be the first, as soon as I’m authorized, to take the vaccine and give it to my family, absolutely. ISAACSON: You say that we know the short and medium term. We have already tested it. People like myself have been in trials in 60, 90 days. Is there anything in the science of putting RNA and people cells that could conceivably make it more dangerous longer-term than other type of vaccines? SLAOUI: There really isn’t. What people need to understand is, RNA is not DNA. DNA, people could conceptually say, oh, it may stick around somewhere and then link to your DNA and do some change. RNA is designed to be destroyed. In fact, a lot of the work that the companies have done, BioNTech or Moderna, has been about protecting that RNA from being instantly destroyed as soon as it gets in our body. When the RNA gets into the cell, it lives for a little bit. It helps as a template to make the antigen, and then it’s gone. It’s gone from the cell. The cell produces the antigen, spits it out. The immune system itself comes and deals with that cell because they think it’s like a virus. And it’s all gone. And that’s really what the data shows, is that, over time, you can’t detect the RNA anymore. So, it’s actually a remarkably fast and effective technology. What we — what happens in — with these vaccines is, we trick ourselves to produce exactly the same antigen as if they had the virus in them. And that’s very hard to reproduce when we produce the vaccines in a big fermenter. That’s really what made this technology so fast and so effective now. ISAACSON: The Pfizer vaccine, in particular, requires super cold supply — super cold distribution chains, and even the Moderna one does. You’re working with the Army. Tell me, how are these things — if next Wednesday and the Wednesday after, it gets authorization, how are we going to get it to places like New Orleans? SLAOUI: So, it’s really worked out in every single detail over the last several months. We have planned. We — what I mean by we is the operation, but within the operation, frankly, my co-leader, General Perna, and all the experience of the — and insights and capabilities of the Department of Defense have planned it to the minute how vaccine doses will be transported from where they are manufactured to the immunization spot areas that each state will have indicated to us. In fact, yesterday, with General Perna, we visited UPS Healthcare. UPS will be one of the transportation strategies. UPS delivers millions and millions of parcels every day everywhere, to every zip code in the U.S. And they will do likewise with the vaccine. FedEx will do the same thing. We also visited some of the warehouses in which the vaccine parcels will be directed in virus direction. Yesterday, also, more than 70 different vaccine parcels have been sent empty to test, right, all the system. I think we have worked out, with Pfizer and with Moderna, the process to deliver this vaccine using what already exists. Every year, 80 million to 100 million doses of influenza vaccine are distributed in the same way, using the same routes, the same transporters, the same warehouses that we’re using for this vaccine. So, that makes us confident that it should be OK. ISAACSON: But Pfizer just indicated and may have to cut back quite a bit on its first few months of delivery. Why did that happen? And how can we get confidence that this — this is — after all the testing fiascoes we have had, confidence that we can lick this delivery system? SLAOUI: Right. So, I frankly don’t know exactly what happened, if anything happened at Pfizer. What I know is, we have an agreement with Pfizer for receiving a certain number of doses. And those are the number of doses we are receiving here in the USA. I think the issues, if they have happened, have nothing to do with distributing the vaccine. They have to do potentially with manufacturing it. I do want to stress, because I think it’s very important to realize, that these manufacturing technologies are unbelievably complex and very different than making a phone or a car, because this is engineering. Those vaccines are biology. And biology, we don’t control as well as engineering. So — and it takes months and months for a batch to go from starting point to actually making sure it has all the quality criteria before you can use it in humans. And we just have industrialized all of that process. And there could be glitches. And I think the best way to deal with that is to be transparent about it, if and when it happens, and explain how we recover from it. The good news, frankly, is each batch makes about one to two million doses. There’s a glitch in one batch, it doesn’t change. Overall, it may change by two days the speed with which the population is immunized. At this stage, we have known. We said we will have 40 million doses of vaccine, immunize about 20 million people in the month of December, between Pfizer and Moderna vaccine, and that’s the plan. ISAACSON: So, 20 million in December. How many in January and February? And once we get through February, and you give me the number, how — what percentage of people who want the vaccine will have it then? SLAOUI: So, 20 million people fully immunized two doses in December, 30 million — that means 60 million doses, 30 million people — in January, 50 million people in February. That is representing 100 million. The at-risk population is estimated about 120 to 130 million in the U.S. The good news, frankly, is the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and/or the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine may very well be also approved somewhere in the month of February and start to also participate to add vaccine doses. We can’t exactly count on them yet, because we need to complete the phase three trial and get to the point we are with Pfizer and Moderna. But we may very well have another 10 or 20 million doses to immunize with in February. Definitely, by the month of March, all the really susceptible populations in the U.S., the older people, the health care workers, the first-line workers, people in long-term care facilities, all these populations will have been immunized, if they wanted to be immunized. And we can start immunizing the rest of the population between the month of March in the month of June. ISAACSON: I have got a scientific question, which is, these vaccines so far seem very efficient at preventing people from getting COVID if they have been exposed to the coronavirus. Do they also prevent the transmission of the coronavirus by people who might be exposed to it? And is there a difference between the different vaccines as to which ones may allow transmission to occur, even if people don’t get sick? SLAOUI: Yes. It’s a very important question from a public health standpoint. And we don’t know the answer to it yet in this trial. It’s very, very cumbersome to be able to demonstrate it, because what you have to do is, you have to swap — because this virus, in many cases, people are asymptomatic, even though they have the virus. You can’t rely on people saying, I don’t feel good, maybe I have a swab or — we have to do swabs every day in people. That’s enormously cumbersome. Now that we know that the vaccines work with 95 percent efficacy, we are designing a study in younger population that has high levels of transmission asymptomatic to exactly address that question. Now, my prediction is, these vaccines are going to be highly effective against transmission, at least shortly after immunization, because you don’t get 95 percent efficacy without quite a remarkably important level of protection. The other thing with the transmission really that is important is, what you don’t want is people having a lot of virus, what’s called virus load. This is what — when somebody has a lot of virus, they transmit a lot of virus to somebody else, that could make that person ill. If somebody has 1,000 times or 10,000 times less virus, they may have detectable virus, but, when they transmit it, they transmit very little bit of virus. And our body is able to deal with very little bit of virus, less able to deal with a big load of virus. That’s my prediction. What’s happening is, some people will have complete protection against the virus, and some people may have a little bit of virus, but so little that they — transmission will be irrelevant. ISAACSON: How do you convince people who are skeptical, including some front-line health care workers who have expressed skepticism? SLAOUI: Yes. Well, I think, first, we need to reflect, why is there so much hesitancy? And I really think part of that — I personally thought about two things that have played to enhance or explain hesitancy. One is people told that the FDA requirements of saying, we need 50 percent efficacy as the vaccine will only be 50 percent effective. The vaccines are 95 percent effective. That’s one. And I think that looks like, OK, now I can have an insurance against this pandemic. The second thing, unfortunately, that happened was, there was a lot of political context in which the development happened, exacerbated, frankly, the criticisms and create — or created tension around whether this could happen, whether corners are cut and these kind of things. And we are where we are today. But we — what I tell people is, transparency is going to be 100 percent. All the data will be shown, are being shown to the FDA and to the independent committee of experts that the FDA use to advise it. They will be discussed in public. Experts from all over the country will have access to the data that will be published in peer-reviewed journal. And they could even access the raw data on request with the companies. Everything will be on the table. Frankly, what I ask people to do is, please keep your mind open. Allow yourself to just hear the data and the information from the experts you trust. There will be a lot of them. And then make up your mind. And I think, if we do that, I think that many, many people who hesitate now will change their mind. ISAACSON: Did you get yourself insulated from any political involvement, where the political appointees might say, rush this one or slow something down? SLAOUI: I asked for that to never happen. And, honestly, it never happened. I have absolutely — I mean, I know that people made talks outside saying the vaccine would be at this time or that time, but that’s outside of the operation. Inside the operation, I never have a call, a meeting where I was told, do this, rather than that, or do that, rather than this, by anybody. ISAACSON: Would you have quit if that had happened? SLAOUI: I would have. And I said it many times. I would have said, I’m out of here. ISAACSON: Have you spoken to or have plans to speak to the Biden transition team, the people like Jeff Zients? SLAOUI: So, not yet. I know that there has been an introductory meeting last week. And I know that meetings are planned next week where we will be discussing this. ISAACSON: Would you stay on for a while if Jeff Zients and the new surgeon general need your advice, or are you committed to leaving in January? SLAOUI: I had set objectives for myself, saying, once we have two vaccines approved and two medicines approved and in use in the population, it will – – it’s time for me to go back to my private life. We’re almost there. And, therefore, I am considering how I will move out of this role. I will absolutely not do anything that will derail the operation. And my affinities are actually high for the new administration. So I have no issue whatsoever helping. But I need to go back to my private life. I mean, I’m not compensated for this. I have many other business priorities that I need to deal with. And, most importantly, my value add here is going down, because we have two vaccines. Two are there. Two are coming up. The next two are in the pipeline. And I can continue helping from far, for sure. ISAACSON: Dr. Slaoui, thank you for being with us. And thank you so much for what you have done with Operation Warp Speed. SLAOUI: Thank you for having me. (END VIDEOTAPE) AMANPOUR: It really is an amazing scientific feat. And as we mentioned, those vaccines must also reach America’s black and Latino communities, which are being disproportionately hit by coronavirus. The pandemic bookends a year which has seen a moral reckoning emerge over systemic racism in the United States and across the globe, really, a movement that was most recently triggered by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too, too many others. But can this moment lead to actual change? Joining me now to talk about this is academic, author and minister Michael Eric Dyson. His new book, “Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America,” explores a troubled history in the form of letters that he wrote to all the people he calls martyrs to the cause of the black struggle. And he is joining me now from Washington. Welcome to the program, Michael Eric Dyson. I just wanted to ask you to pretty much let’s talk first about what president-elect Biden and vice president-elect Kamala Harris — and you just heard Dr. Moncef Slaoui — talking about the most vulnerable communities needing to get it pronto, this vaccine. But, of course, in the black community, there has been historical in justices, the Tuskegee scientific experiments and justifiable anger and skepticism. Do you think this is going to play into so many decades later, when a vaccine is so much needed by that very community? MICHAEL ERIC DYSON, AUTHOR, “LONG TIME COMING: RECKONING WITH RACE IN AMERICA”: I think that — first of all, thanks for having me. I think there is skepticism. There is a kind of wariness in regard to the use of science in regard to black bodies. Black people are not afraid of science. They are afraid of scientists. They are afraid of the manipulation of data for the purposes that are nefarious or highly questionable, that are unscientific, but using scientific means toward non-scientific ends. So, yes, there’s widespread conspiracy and skepticism in some pockets of black America. But I think that will be overcome once people begin to see the scientific proof that these vaccines indeed enable and enhance health, and not deter them. AMANPOUR: And, of course, we have heard — I mean, the guy who’s right there in the interface, the call-face, Dr. Slaoui, who is the scientific adviser, attesting to their safety, and people like President Obama, along with Presidents Clinton and Bush, saying that they would take them publicly, on camera, and do everything that they could do help — help people figure out that this is safe. DYSON: Right. AMANPOUR: Is that going to be enough? And I actually want to ask you whether other people should do that. You have dedicated the book that we’re going to be talking about to LeBron James. DYSON: Right. AMANPOUR: So, I just wonder whether you think that some of these very popular and well-known and trusted members of the black community can help here? DYSON: I think they can. I think that, yes, it helps to have President Obama take that vaccine or Presidents Clinton and Bush, perhaps if famous athletes did so as well. And I hope it’s with the recognition that black people have due — in due course, have had legitimate reasons to be skeptical, not enough to prevent them from taking the vaccine. But I think those who are in positions of power and authority scientifically or culturally or even politically should understand that legacy, that it is the legacy of white supremacy through a needle. It’s the legacy of white supremacy through a white coat. It’s the legacy of white supremacy through the manipulation of scientific rhetoric and discourse to justify the unintelligence of black people, the inferior capacity to learn of black people, parts of which persist in our own day, when we think about the work of Charles Murray and other people, who have tried to legitimate a bell curve suggesting that black people are inherently inferior when it comes to intelligence, must be expanded when we look at the range of sciences that are deployed to either enhance or somehow undercut black people. Having said all that, it does make a difference if some of these famous black people and folk get out there and other trusted figures to suggest, hey, we understand why you have skepticism and wariness, but this thing works. And guess what? The disproportionate impact on black and brown bodies suggests that we need to take this vaccine. And, furthermore, we ought to solve not simply the taking of a vaccine, but the lack of access of black and brown people to health care organizations that would prevent them from being so vulnerable to it in the first place. AMANPOUR: And, indeed, what you describe is really grotesque. And I just wonder in general about your book “Long Time Coming.” You do dedicate it to LeBron James. Tell us why before we get further into it. DYSON: Right. Well, I think LeBron James has been exemplary as the most remarkable athlete to put his reputation on the line, to leverage his platform in defense of ordinary black people. He has — not since perhaps Muhammad Ali has an athlete of his stature, of his global recognition, of his enormous popularity been willing to leverage all of that, in the face of that popularity, at the height of his global acclaim, in defense of what some would consider to be a controversial subject. That is that black lives should matter. That shouldn’t be controversial, but it remains so in many quarters. And so he’s been able to do that and to garner awareness in many pockets of the culture, some of which are sympathetic to black people, others of which may not have been necessarily inclined to do so. So, I wanted to celebrate a figure who, in the middle of the Black Lives Matter protests, led basketball players, along with Chris Paul and other figures, to stop their work when Jacob Blake was killed — was shot — I’m sorry — in Kenosha, Wisconsin. And they were saying, enough is enough, and we have got to make this point more poignantly. AMANPOUR: So, it leads perfectly into the substance of your book, “Long Time Coming.” And you talk about the martyrs. You use that word martyrs, which is a very, very evocative word. And you write this book in the form of letters to individuals who have been killed in this terrible struggle. DYSON: Right. AMANPOUR: Tell me about martyrs and the overall message that you are trying to get across. DYSON: Right. Well, victims, of course, of police brutality have died for some time who are black. But I think martyrdom is a deliberate choice. And I thank you for emphasizing that, because their lives, through no intent of their own, right? Most martyrs do intend, I will take up a particular issue, I will bear my cross, I will be willing to die and, therefore, be martyrs for a cause. These people have been forced to become martyrs. The consequence of their deaths have led to enormous changes of consciousness and galvanizing impetus among African-American people. It has also articulated a social imperative to change the structure of society. So, in that sense, Emmett Till didn’t choose to die at 14 years old, but his death has been used since its grotesque and grim occurrence, its grisly enactment in 1955, as a symbol of social resistance among African-American people and the determination to fight back against white supremacy. So are the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and on and on. So, I think these figures that I have highlighted in my book, including Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Elijah McClain, George Floyd and the like, are martyrs because their cause has been taken up. They have been made sacred in the aftermath of their deaths. The posthumous acclaim to which they have been subject, in one sense, enacts a moral utility among black people. What is that moral utility? To express to the culture that their deaths are unwarranted, unjustified, and heinous, because they contradict the fundamental principles of justice, truth and democracy in our culture. And they repudiate the beautiful embrace of all peoples, e pluribus unum, out of many one. So, their deaths serve as a warning, as a reminder and as an encouragement at the same time. AMANPOUR: So, let’s start with the one who — well, the one who you opened the book with, Elijah McClain. He was 23 years old. And in 2019, he’s a young massage therapist. He’s walking back. He’s in Colorado. And somebody calls the police saying that he looks sketchy. And it leads to his death. I want you to tell me a little bit about the facts. And then I think you have got a passage that you’re going to read for us, a particular passage of your letter to him. DYSON: Yes. Yes, exactly. First of all, it was horrible. A 23-year-old young man, some say, on the spectrum, but a beautiful sensitive soul who played a violin to pigeons and birds to soothe them, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, a young man who, one of his co-workers said, had a gold orb that sort of surrounded him as he walked and as he came to work. This was extraordinarily painful because that sweet soul was crushed into nothingness by the brutal force of a police contingent that disregarded his request, please, respect my boundaries that I’m speaking, and they did not. They indeed hugged him so closely that they didn’t asphyxiate him, but they did knock him out. They did put a chokehold on him that rendered him unconscious twice. And then when an EMT showed up, Ketamine was administered, the man went into shock. A week later, after being taken to the hospital, he died. This was an enormous tragedy that didn’t get the kind of acclaim it would have ordinarily receive perhaps had there not been other news to block it out. But with the death of George Floyd it was revived in the itinerary and the agenda of black freedom because his death became exemplary of the kind of hostilities to which black people subject when they encounter the police. AMANPOUR: Would you read a little bit of the passage? DYSON: Yes. Elijah, you showed you were a sensitive and lovely soul. You did this despite enduring bouts of crying and vomiting. Elijah, you, too, like Eric Garner and George Floyd said, I can’t breathe. You told them, I’m just different. That’s all. I’m so sorry. You told them I have to gun. I don’t do that stuff. You promised. I don’t do any fighting. Then you pleaded, why are you attacking me? I don’t kill flies. I don’t eat meat. As if your penchant for peacefulness and your dietary discipline might somehow convince them that your life was worth sparing. AMANPOUR: It’s really heartbreaking. And I want to ask you specifically because you address this book to white people as well. You talk directly to white people saying, my fellow Americans, I beg of you to first consider this. Do you realize how weary I am, how weary we are? Millions of black folks in this country. And right from the start, it’s a troubled we, a complicated we, a dispute we of being denied recognition as Americans or even as human beings. I guess it’s massively important that white people hear this. And we’ve heard, you know, President-Elect Biden say to the black community, when I needed you, you had my back. Now, I’m going have your backs. DYSON: Right. AMANPOUR: Do you think now, finally, a change is on the way? DYSON: Yes, I think so, and that’s a nice tag too, “Long Time Coming,” the name of the book, a change is going to come is the Sam Cook song from which that title was derided. So, I knew that Christiane Amanpour was a remarkably brilliant journalist, as musicologist as well, is beautiful to know. Yes, I think that finally America will begin to grapple with some of the persistent bigotries, the plagues with which black people have been cursed, that have to be addressed, that have to be dealt with. I think that finally, many white brothers and sisters woke up, and we can be in harsh judgement of them. My God, did it take George Floyd’s death, did you not see slavery, did you not see Jim Grow, did you not see the civil right struggle, the black freedom struggle, did you not see white water fountains and black water fountains or brown versus board education? I’m not interested in that. What I’m interested in is that now that people are awake, what can we do? Now, that people are sensitive to the call and claim of black liberation, of emancipation of resistance to being demonized and marginalized in the culture, of the insistence, we don’t want any more than anybody else but we want what everyone else ostensibly and theoretically receives, recognition as a human, the decency of their own identities, the bodies to be protect and served by the police and not to be harmed. I think that this is a pregnant moment to begin to engage in that long conversation, that long overdue dialogue that we need to have in order to transfer the ideals of the Declaration of Independence to march them from parchment to pavement and to make sure that they are not turned in ink but that they are let loose upon the American culture for which they were meant. And so, in that sense, I think we do have the opportunity to make a difference, to challenge some of the madness that has been going on and that perhaps together we can begin to realize some of the noble ambitions of the democracy that all of us have invested in. AMANPOUR: A rallying cry for our time. Michael Eric Dyson, thank you so much for joining us. And now, we take an electrifying stroll down memory lane with singer/songwriter, Yusuf/Cat Stevens. He shot to stardom 50 years ago with music and lyrics that were full of poetry, spirituality and great beats, of course. “Tea for the Tillerman” from 1970 has been called a master and “Mona Bone Jakon,” also that year, featured the haunting track, “Lady D’Arbanville.” Here’s a vintage clip which was unearthed and released for the first time just this week. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) YUSUF/CAT STEVENS, SINGER-SONGWRITER: My Lady D’Arbanville, why does it greet me so. But your heart seems so silent, why do you breathe so low, why do you breathe so low. My Lady D’Arbanville, why do you sleep so still. I’ll wake you tomorrow and you will be my fill, yes, you will be my fill. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: Now, to mark half a century since both hit albums, Yusuf, is not just re-releasing but reimagining them as well. Indeed, over this past half century, the artist has also re-imagined himself to an extent as we discussed when we joined me from home in Dubai. Yusuf/Cat Stevens, welcome to the program. YUSUF/CAT STEVENS, SINGER-SONGWRITER: Thank you very much. Nice to be here. AMANPOUR: So, tell me about the 50th anniversary, re-release and reimagining of your classic “Tea for the Tillerman.” What was the objective? STEVENS: Well, you know, after 50 years, where have they gone? You know, that’s the first question. But after 50 years, you gather a lot of experience and, you know, you’ve learned a lot, you’ve gathered a lot of ideas. And, of course, I’ve been through many, many changes, some of which we will probably talk about today. But, you know, it was — the 50th was coming up. My son, you know, who kind of prods me whenever things, you know, need to be done. He said, well, what are we going to do? And he said, what about — why don’t we re-record it? I said, that’s a good idea. You know, I love a challenge. And that was the idea behind it. And really just kind of to pay tribute really to this very important album, which a lot of people could have recognized me for this album more than any other. AMANPOUR: Well, I mean, “Father and Son” is a classic. Every son, every father can relate to these words and to this notion. So, I’m going to play just a clip of the re-imagined version on “Tea for the Tillerman 2.” (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) STEVENS: Take your time, think a lot, think of everything you’ve got that you will still be here tomorrow but your dreams may not. Oh, how can I try to explain because when I do he turns away again, it’s always been the same, same old story. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: It’s pretty amazing because you are now at, you know, 50 years plus singing the father and your young self of 50 years ago is singing the son as you did back then. It’s a remarkable new way of telling this story. STEVENS: It is. I mean, I’m afraid that I continue to take the son’s side of whatever — you know, even when I’m singing the father side. But to be honest, I’m waiting to get into the son because I was into change, I was into, you know, experimentation and exploring, and I think that the son represents that. You know, the actual origin of these songs, I’ve got to tell you, was originally because I was trying to write a musical, and I chose the Russian revolution, like, you know, something not quite easy to do. But — so, when it came to this story, it was the story of basically two families. One was Alexandra and Nicholas, you know, there (INAUDIBLE). And then you’ve got this little family in the countryside. And the son wanted to join the revolution and the father just said no. Just stay here. Everything is fine, you know. We can work this out. And so, this song was quite revolutionary in its background and its intent, but it hits all sorts of levels. I mean, you know, the family is always at most important, you know, relationship we ever have. It’s our parents, it’s our, you know, brothers and sisters. And so, it really strikes a chord and continues to. AMANPOUR: And, you know, your lyrics have been described as poetic, spiritual. Some have said that it even, you know, belied your very, very young years. I mean, I think you were, I think, 22 when you started having and doing these amazing hits. And as you say, they have actually stood the test of time. But the father/son and the revolution, I just want to ask you, is that — does it have any personal resonance? Was your father against you becoming, you know, a singer, a pop star at that time? STEVENS: No, no. He bought my first guitar. I mean, he was great. Dad gave me all the freedom I need. I mean, he was a journeyer himself. He was an adventurist. You know, he left Cyprus, he went to Egypt, married, you know, had children and then went on to America, you know, during the roaring ’20s. Can you imagine? So, you know, then he came back to U.K. And by that time, he had sort of separated from his first wife and he met my mother. And so, you know, he was an adventurer. And I think I’ve taken on a lot of those characteristics, obviously. AMANPOUR: You talk a lot about transitions, and your life story is, you know — I mean, it’s like 12 different lives packed into one span of time, it’s extraordinary, including a very serious brush with tuberculosis. And that, I think, was a turning point moment for you where you could — tell me about it. How old were you, and what did that mean in your sort of, you know, timeline of being a singer? STEVENS: Well, it was like I’d had — in a way I was very, very lucky because my first song, my first record, you know, it was a hit called “I Love my Dog” back in 1966. But then, of course, I had to get into the — I was doing the business. I was doing everything that they were telling me, working three nights to three shows a night, really struggling and, you know, playing with Jimi Hendrix and all that stuff, it compounded, obviously. And eventually, I became sick. I couldn’t take it. And my body said no. I contracted tuberculosis. And then suddenly, I had to go back to sort of square one, and it was just me in the hospital, you know, kind of reviewing my life and thinking about the future. And I had a book with me about Buddhism, and that was the key really to my journey. The first steps I took on the spiritual journey was because I read this book about Buddhism. And, you know, I was a Christian. I was having, you know, a very strong Christian background in a way, whether it was school, you know, not that (INAUDIBLE), it was the school. They really drilled it into me. But — and then — so, I went on this journey and I started to make my own music again. But this time, my music was mine. I decided to take control. And I was very fortunate, again, to meet somebody who really believed in me, Chris Blackwell, who, you know, ran the Island Records label. AMANPOUR: Yes. STEVENS: And he just — he heard “Father and Son” and he just wanted to sign me up. And then, you know, that’s where my second career began, and that’s when a lot of people in America got to know me, and to a point where everybody almost thinks I’m American. That was just so big. AMANPOUR: We’re going to play another clip from “Hard Headed Woman.” It’s also on “Tea for the Tillerman.” But this is the original. Let’s just play it. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) STEVENS: I’m looking for a hard-headed woman, the one who will take me for myself. And if I find my hard-headed woman, I will need nobody else, no, no, no. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: One of the reasons I actually wanted to play that is because, for me, it’s amazing to hear you, as a man, singing that you want a hard- head woman. I haven’t actually encountered many of those. Is that real? Did you really want a hard-headed woman to make you do your best as you sing? STEVENS: Well, if you think about marriage as a partnership or, you know, the woman who comes into your life has to have a strong personality. I mean, you know, to deal with me, you’ve got to have a strong personality. Probably everybody says the same thing. But, you know, it definitely means that I want somebody who can keep me going in the right way. And that was, you know, until — when I wrote that song, I didn’t really know who I was looking for but I knew it was somebody who was going to be kind of backbone for me. And, you know, when it comes to the differences between or — there’s no war between male or female. It’s just — but, you know, you’ve got to have a mind. And these days, you know, we’re seeing that this is — I mean, every — almost every other song in the hit parade, most of the songs, are, you know, ladies. I mean, they’re all — you’re dominating this whole thing now. Going crazy. I think I’ll retract that song. No. AMANPOUR: No, no. No, you won’t, because we’re just leveling the playing field and taking nothing away from you. But I want to the talk to you a little bit about your — you know, your different journeys and actually identities, and one way to do that is just to ask you about, you know, you have gone through quite a few names. You grew up as Steven Demetre Georgiou. Professionally, of course, you were Cat Stevens. You converted and became Yusuf Islam. And now, we call you Yusuf/Cat Stevens. Tell me about the — well, what was it like growing up in England at that time, being a Greek Cypriot and having a name like that? Did you encounter any pushback or even bullying or anything at school? STEVENS: Yes. I mean, you know, Steven Demetre Georgiou was not going to get you very far, to be honest with the guys. You know, they took the (INAUDIBLE), obviously, and things like that. But my dad had a restaurant. So, I had kind of an up on them. And so, that gave me a little bit of a stature. And I think that if you look at, you know, the whole — the why did I want to start making music, because was something within me that was not being recognized because I was maybe looked at as — like this or like that. And I was trying to find out who I was because my father was from Cyprus and my mother from Sweden and was born — you know, I was born in London. You know, we were living above a shop with a French-sounding name, you know, Moulin Rouge. I mean, so I had to make sense of this. And this was a big, I would say, propulsion in my life, is to go and find out who I was. That means sometimes you change your name. You know, first, I was a song. You know, a brother. More so, you know, now, I’m a daddy, I’m a granddaddy. So, we all have — we have different names as we go through life. But I definitely made some sharp turnings, you know, you can say that. AMANPOUR: And you were a Christian and you became fascinated by Buddhism, and then you converted to Islam. What was the moment that led you to that? STEVENS: Well, I mean, I don’t know if many of the viewers know the story but, you know, essentially, it was — I had kind of reached the top, the summit, you know, of stardom and everything, superstardom you can call it. And everything was kind of — because I wasn’t really happy and I was still, you know, desperately empty inside. I needed something. And I went — one day, I went for a swim, it’s kind of 1975, and it was in Malibu. And it was not a very good time to go swimming, and anyway I did, and then I started to try and swim back. That wasn’t going to happen. Suddenly, I realized there was very few moments left in my life. At that moment — I used that time just to call out to God. I said, God, if you save me, I’ll work for you. That was it. And then a little wave came from behind me. I can’t describe how it was, I don’t what happened exactly, but then I was able to get back to land. This wave had pushed me and suddenly I had the energy. I was back. That was the turning point. I made — I had made a promise after that. My brother visited Jerusalem. He was married to an Israeli girl, and he was having his honeymoon and, you know — and then he saw — and then he discovered Islam in the middle of Jerusalem, he found this dome, you know, and wanted to know more. When he came back to London and we met there, he gave me the birthday present, it was the Koran. And that’s the first time I ever even thought about Islam because it was kind of slightly repulsive to me because, you know, father was Greek, you know, and all the things that we grew up with, you know, Ali and the 40 thieves and all that stuff, you know, you don’t really trust them, do you. So, I had to get past a lot of, you know, barricades. But when I heard this, this book is not going to hurt me, you know, it’s a book. So, I started reading the book, and that was it. I just discovered, you know, Muslims believe in God, and all the prophets and in the day of judgment and the goodness and so many things that I knew already was, you know, intrinsically in my body and in my soul. And it came to the point where I realized that was the promise I made and I fulfilled it, God willing. AMANPOUR: One of the things that clearly saddened your fans was having found that. You also decided to not perform anymore. And I think, famously, you either gave away or sold — anyway, you got rid of your huge collection of guitars and you stopped performing. Why did you — well, I guess what made you come back to it after all that time? STEVENS: Well, you know, I did go through a whole period, of course. I mean, I was so happy to have found who I was, you know, Joseph, by the way, was always my favorite name. And Joseph, well, the chapter in the Koran, which really opened my heart. So — but when I came to sort of living the life of a Muslim, that was fine until things started going wrong in the world, and, you know, I didn’t have anything to do with it. But, unfortunately, I was a bit famous and, you know, I was like a Muslim. It was kind of easy to kind of — well, let’s ask him, you know. And so, then I get involved in all of this stuff. When it came to — first of all, I gave my music up because I had so many other things I was doing. I was married. I had my family. And I was in education and then philanthropy and, you know, relief. You know, but then came Bosnia. And when Bosnia happened, it was a wake-up call because it was the disaster that I couldn’t believe that was happening and the world was not doing anything about it. And I saw these people and they were still singing, and it just struck me so hard that we need music. We really do. When we have knock else, you know, and when we have still the chance to raise our spirits with a song, you’ve got to do it. And that kind of was the beginning of my journey back to music. AMANPOUR: It’s very resonant for me because for myself and my generation of journalists, Bosnia was a defining moment as well. And I just wonder whether now are you back? Are you going to be performing? Are you going to continue or is this a one-off for the 50th anniversary? STEVENS: Well, no, I’ve got so much going on. I’ve got — you know, by the way, I’m writing my autobiography. So, get ready, you know. And plus, I was recording already. I had finished more or less another album, about 11 songs, new songs, and then came the 50th. And then my son said, we’ve got to do something. So, then that diverted us into, you know, making “Tea for the Tillerman 2.” So, that’s where that was. But now, I’ve still got another album ready to go and that will be released probably next year sometime. And there’s some beautiful songs. I mean, you know, I was given a gift, you know, to be able to keep on writing and keep on singing. People, when they hear my voice, they say, how did you do that? You know, how come you don’t sound differently? Well, of course, I don’t drink, I don’t smoke and all that stuff. But anyway. AMANPOUR: Now, can I ask dare to ask you whether you have a guitar at hand or a keyboard and whether you would play a couple of notes for us? STEVENS: Well, I don’t know what you want me to sing. Hang on. AMANPOUR: Well, “Wild World” or “Father and Son” or whatever you want. STEVENS: This is really impromptu. Let’s tune it up a little. I told you it wasn’t my favorite guitar. I listen to the wind, to the wind of my soul. Where I’ll end up, well, I think, only God really knows. I’ve sat upon the setting sun, but never. Never, never, I never want to water once. No, never, never, never. There you go. For you. AMANPOUR: Wow. Oh, wow. That is so perfect. Thank you so much. What a gift. STEVENS: God bless you, my dear. And let’s hope we meet again. AMANPOUR: Let’s hope. Yusuf/Cat Stevens has still got it and that was “The Wind” from his 1975 album “Teaser and the Firecat.” And Yusuf/Cat Stevens’ celebration continues this weekend as 40 artists cover his work at the virtual festival, Cat Song. And finally, we want to recognize some of this year’s most essential workers. This year’s winner of the million-dollar global teacher award is truly inspiring. When Ranjit Disale arrived in — to teach at a primary girl’s school in a small village in Western India, attendance was very low, and the curriculum wasn’t even in the students’ local language. So, he learned that language, translated materials and developed special digital learning tools as well. And they are now used across India. Now, at Ranjit’s school, no one misses a class. Yes, that is it for our program tonight. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” and join us again next time. (COMMERCIAL BREAK) END |