1. His first film prompted the formation of a political party that later overthrew a government.

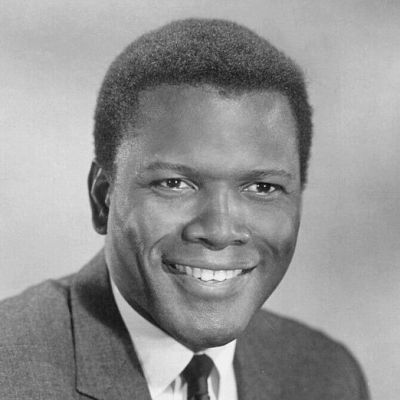

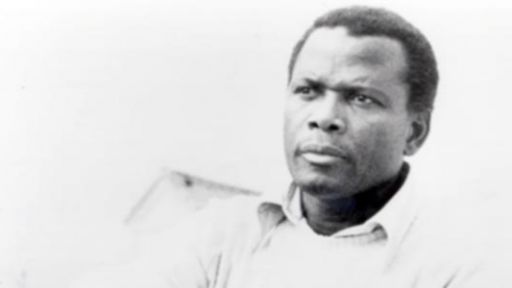

Before he found his way to Hollywood, Sidney Poitier spent his childhood on the remote beaches of Cat Island in the Bahamas, where he grew up the son of poor tomato farmers. The youngest and most rambunctious of seven children, Poitier was on the verge of attending reform school when his father sent him to live with family in Miami, Florida instead. From there, he moved to New York City at the age of 15 with just three dollars in his pocket and decided he wanted to act in the movies. Poitier listened endlessly to radio programs to help him learn to enunciate and lose his Bahamian lilt while working as a dishwasher. The effort paid off, and seven years later in 1950, when the budding actor was 22, he starred in his first film, “No Way Out.” The pioneering noir picture was one of the first films to tackle the topic of racial tensions in America, and broke with typical portrayals of Black characters as subservient and cowering. The film’s release also coincided with the nascent civil rights movement in the U.S., and was subject to strict censorship rules and bans, particularly in Southern cinemas, but also in the Bahamas, where the country’s colonial film board refused to show the film. Outraged Bahamians of African descent soon gathered together to form the Citizens Committee to demand the ban on the movie be lifted. They won.

“They aroused citizens all over this land and demanded that the film be shown,” recalled former Governor-General of the Bahamas Sir Orville A. Turnquest. “After that, they decided to stay together.”

Off the back of their success, a movement arose, and then the country’s first political party, the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP), was born. Formed to advance self government, wider political representation, and call for more government social programs, the party eventually formed a majority party in 1967, leading to the country achieving full independence from English colonial rule in 1973.

2. He chose roles that would advance the depiction of Black actors and characters on screen.

After his first foray into film, Poitier continued to star in features that subverted typical expectations of Black characters and actors of the time and dealt with race head on. “Cry the Beloved Country” (1952), which examined the scourge of apartheid in South Africa and “Blackboard Jungle” (1955), a social drama based on an interracial inner-city school, were just some of Poitier’s acting achievements during this time. In 1958, his role in “The Defiant Ones,” a film that broke racial barriers, earned him an Academy Award nomination for best actor. It was a first for Poitier, and also for any Black actor in a leading role.

Just a year later, producer Samuel Goldwyn offered Poitier a role in the movie adaptation of George Gershwin’s opera “Porgy and Bess” — a tale centered on a poor, Black street beggar who tries to save his object of desire from her thuggish and violent partner. At first Poitier refused Goldwyn’s offer to play Porgy because he objected to the depictions of Black Americans in the opera. But the actor eventually relented after being warned that Goldwyn had the power to end his career, he said. Poitier was noticeably absent from the premiere in 1959. Four years later, Poitier starred as Homer Smith in “Lilies of the Field” – a lighthearted film that steered away from racial commentary. Nonetheless his role in the film helped advance representation in Hollywood when Poitier became the first and only Black person to receive an Oscar for best actor for his role.

After that, Poitier starred in a host of other films that were provocative and had a social conscience. “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” the first big film about interracial marriage in Hollywood, was banned in the South when it premiered in 1967, but it launched Poitier’s career to even bigger heights. That same year, he starred in all three of Hollywood’s biggest box office hits, and was subsequently named the number one money-making film star in the world.

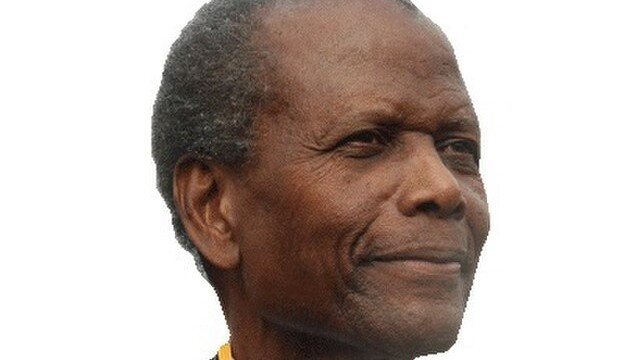

3. He reshaped his career as a director and made movies to advance representation and equity.

When Poitier started out in Hollywood, he lamented the portrayal of Black people as “always negative, buffoons, clowns, shuffling butlers, really misfits,” and said he “chose not to be a party to the stereotyping.” He wanted to reflect the types of Black Americans on screen that he saw in everyday life, but his role in films that favored integration also drew heavy criticism from some Black critics who said he wasn’t revolutionary enough.

Despite his efforts with the civil rights movement and to desegregate Hollywood and beyond, Poitier was rebuked for the very thing he had tried to avoid. One article in the New York Times by a Black writer lambasted him as a “good n—–” and a “showcase n—–.”

“It was a very tough article for me because it came at a very delicate time in my life and my career,” Poitier said. “I had had tough articles before but the extent to which this was — to my mind — totally untrue, bothered me… I never forgot it.”

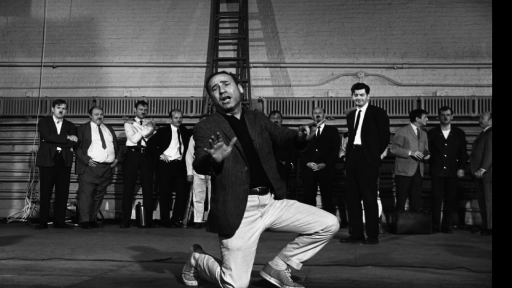

In the wake of such criticisms, Poitier took a break from Hollywood and returned to the Bahamas to reassess his priorities. He flirted with the idea of never acting again, but decided to pivot to work behind the camera. In the 70s and 80s, Poitier returned to Hollywood to direct a slate of films, some of which he also helped write and co-star in. These films created opportunities for actors of color to appear in a new genre of comedy films that were a big hit with Black and white audiences alike.

“I wanted to make movies in which Black people could sit in the theater and laugh at themselves without restraint and feel good about it,” he said.

After 10 years of not acting, Poitier returned to the screen in such roles as FBI agent Warren Stantin in “Shoot to Kill” (1988) and as civil rights icon Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and de Klerk” (1997). Between 1997 and 2007, Poitier was also named as the Bahamian Ambassador to Japan, during which time he continued to make and star in movies, capping off his more than five-decade film career in 2001 with “The Last Brickmaker in America.”

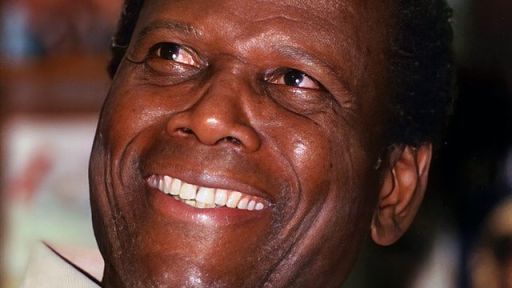

4. While he fought for racial equality, he also rejected efforts by the media to continually center the discussion around his Blackness, and refused to be defined by race.

At a press junket, Poitier famously rebuffed reporters, saying, “You ask me questions that continually fall within the ‘negro-ness’ of my life. You ask me questions that pertain to the narrow scope of the summer riots [referring to the summer of civil unrest in 1967]. I am an artist, a man, American, contemporary. I am an awful lot of things, so I wish you would pay me the respect due and not simply ask me about those things.”

During the making of the documentary Sidney Poitier: One Bright Light, director Lee Grant admitted during an interview with James Earl Jones that Sidney had expressed that he wanted her to “think in broader terms” while shaping the narrative of her film.

“Sidney said to me when I asked him to do this, he said, ‘You know, I want you to think in terms of my being more than a Black man’,” said Grant. “‘I mean I know that we’re going to be talking about civil rights and racism in the country and everything like that, and I want to. But I also want you to think in broader terms. I am not only a Black man, I’m a man with interests, and I’m a thinker, and I’m an ambassador to Japan now… I am tired of always going over the same old question which is, you know, why are you, or why were you the ‘Black actor’?'”

By Liz Fields