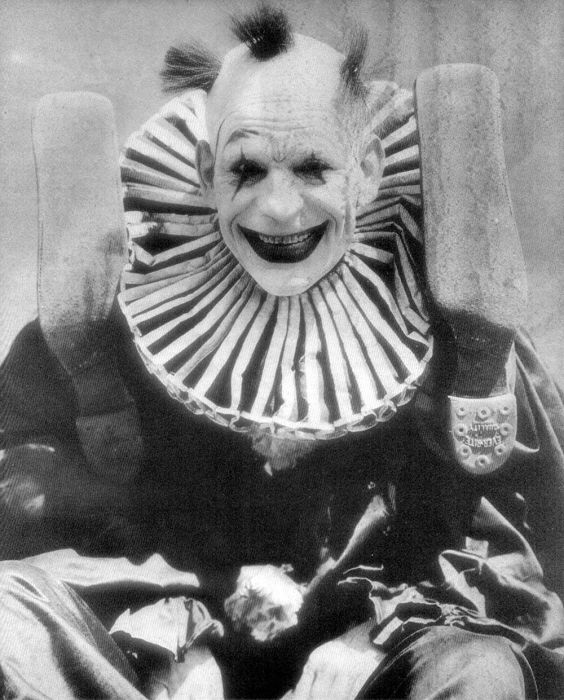

Actor Lon Chaney tested the boundaries of on-screen performance, pushing the limitations of his body and innovating with prosthetics.

While German expressionist classics like “Nosferatu” defined early horror cinema, Chaney’s various incarnations left America’s imprint on the genre. His characters mark some of the earliest experiments in body horror on-screen, and his surreal, yet human, monsters live on in our visual storytelling today. Here are five facts about this horror icon.

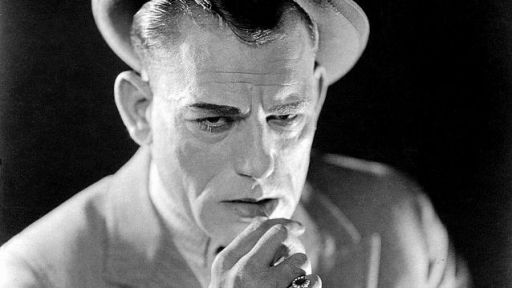

1. Chaney was extremely private.

Born to Deaf parents in 1883, it is said Chaney had a unique ability for non-verbal communication, which allowed him to fully inhabit his characters – especially in the silent era. His acting range and physicality made him an asset for the studios, often portraying more than one role in a production. Incorporating humanity into each character, he defined the early cinematic language of American horror films like “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” and “The Phantom of the Opera.”

One can only speculate about Chaney’s privacy, whether it was out of shyness or a publicity ploy. He was quoted as saying, “Between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney,” and even his real voice was contested amongst audiences as he used five variations of it in his only sound film, the sound remake of “The Unholy Three.”

“Man of a Thousand Faces,” the 1957 biographical drama starring James Cagney, took many creative liberties with Chaney’s story, further perpetuating myths about his life.

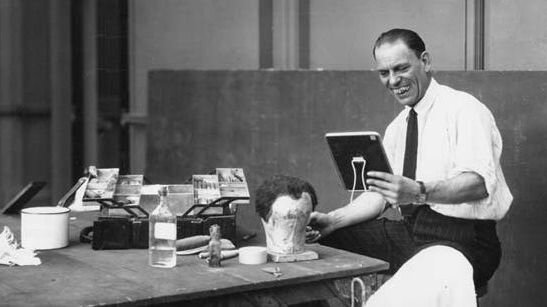

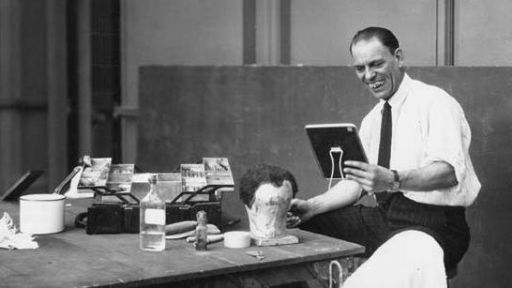

2. Chaney wrote the Encyclopedia Britannica entry on “makeup.”

In contrast to many of the other silent film stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton who perfected their consistent on-screen personas, Chaney’s career was one of continual transformation. In bringing a role to life, he often went to extreme lengths to achieve his characters, such as undertaking painful prosthetic applications and costumes. For both “The Phantom of the Opera” and “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” Chaney used wax, false teeth and greasepaint to change his face, carefully recreating the original descriptions from their respective source material.

He once said that “the success of the makeup relied more on the placements of highlights and shadows, some not in the most obvious areas of the face.”

Chaney’s knowledge of makeup was so vast that he wrote the entry on the subject for an edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1929.

3. Chaney was co-stars with Joan Crawford.

Actress Joan Crawford spoke highly of her time with Chaney, citing him as an influence for her film career and calling him “the most intense, exciting individual” she’d ever met. Together they starred in “The Unknown,” a silent film about circus performers. Charlotte Chandler’s biography of Crawford, “Not the Girl Next Door,” quotes her as saying:

“With him I became aware for the first time of the difference between standing in front of a camera and acting. . . . Until then I had been conscious only of myself. Lon Chaney was my introduction to acting.”

Though “The Unknown” received mixed reviews, the June 13, 1927 review in The New York Times said, “It is gruesome and at times shocking, and the principal character deteriorates from a more or less sympathetic individual to an arch-fiend.”

4. Chaney believed his characters could find redemption.

It is said that Chaney’s upbringing made him sensitive to the experiences of “outsiders.” Early horror movies experimented with non-formative figures, reminiscent of many of the disabled and wounded veterans who had returned from World War I. David J. Skal, a biographer of Tod Browning (one of Chaney’s collaborators), noted that many of these films captured the feeling of powerlessness created by the national trauma of the war and subsequently the Great Depression, likely exacerbated by the growing Eugenics Movement. Known as “The Man of 1000 Faces,” Chaney’s work reflects not just the genre itself, but the vulnerabilities of a society overcoming World War I and empathy for the ostracization of marginalized groups.

Chaney rarely gave interviews, but in a 1925 autobiographical article for Movie Magazine, he wrote:

“I wanted to remind people that the lowest types of humanity may have within them the capacity for supreme self-sacrifice. The dwarfed, misshapen beggar of the streets may have the noblest ideals. Most of my roles since ‘The Hunchback,‘ such as ‘The Phantom of the Opera,’ ‘He Who Gets Slapped,’ ‘The Unholy Three,’ etc., have carried the theme of self-sacrifice or renunciation. These are the stories which I wish to do.”

5. He discouraged Lon Chaney, Jr. from pursuing a career in show business.

Although Lon Chaney, Jr. would also go on to leave his mark on the horror genre with his portrayal of The Wolf Man and other monsters, his father had hoped he would avoid show business and encouraged him to pursue another career. When Lon Chaney, Sr. passed away in 1930, he was one of the most popular silent screen stars. His son, originally named Creighton Chaney, hoped to create a name for himself in Hollywood outside of his father’s shadow, but he was only able to land small roles:

“I did every possible bit in pictures. . . . Had to do stuntwork to live. I bulldogged steers, fell off and got knocked off cliffs, rode horses off precipices into rivers, drove prairie schooners up and down hills.”

He changed his name in 1935 and began to achieve stardom for his portrayal of Lennie in John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” a few years later. When he was cast as The Wolf Man in 1941, Universal dropped the “Jr.” and billed him just as “Lon Chaney”—further creating confusion for audiences. Chaney, Jr. would go onto play The Wolf Man in several sequels, as well as The Monster in “The Ghost of Frankenstein” and Dracula in “Son of Dracula.” On what set his characters apart, he said:

“All the best of the monsters played for sympathy. That goes for my father, [Lon Chaney, Sr.], Karloff, myself and all the others. They all won the audience’s sympathy. The Wolf Man didn’t want to do all those bad things. He was forced into them.”