Lena Horne was one of the most recognizable actors, singers and civil rights icons of her era.

Throughout her 70-year career, Horne struggled to forge her own identity amid deep-seated racism and segregation in Hollywood. But ultimately, her fight against discrimination helped break barriers, challenge stereotypes and pave the way for more Black women to find their own place in the industry. Here are five ways Horne revolutionized the entertainment industry and helped improve standards of representation for Black performers:

1. She fused activism and politics with art

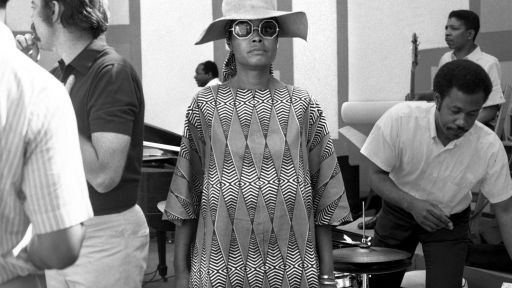

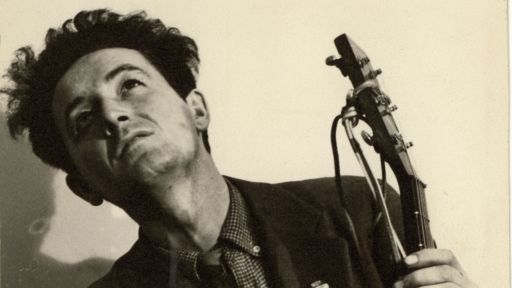

In the early ’40s, when 23-year-old Horne’s career was taking off, she began performing at New York City’s famed Café Society — the only integrated nightclub outside of Harlem at the time. There, celebrities and socialites mixed with performers and left-wing intellectuals — including communists. “I began to thrive,” said Horne, “I was introduced to great writers and painters, actors, and intellectuals. People like Langston Hughes, and Orson Welles, Billie Holiday, Art Tatum, Duke Ellington.”

It was also at Café Society that Horne met Paul Robeson, a Black actor and intellectual who openly supported socialism and advocated for racial justice, economic fairness and civil liberties. Robeson greatly influenced Horne, and awakened her to her own ability to speak out and help others as a tonic to her frustrations about the racism she experienced in the business. “He said, ‘Look, you’re a Negro and that is the whole basis of what you feel and it’s the basis of what you will become.’ And he gave me identity – he grounded me,” Horne said.

Horne then joined groups such as the Council for African Affairs and the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee. A year later when she moved to Hollywood, Horne worked with Walter White, the leader of the NAACP to try to change the way Black women were represented on screen.

2. She was the first Black woman to sign a long-term contract with a Hollywood agency

In 1942, Horne became the first Black woman to sign a long-term contract with a major studio. The actor tells the story of one particular meeting when Horne’s father told MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer that his daughter was “not going to be in a Tarzan picture and run around in a leopard skin.”

“In any case, I became the first Black to a long-term contract. Seven years,” she said. “They said, ‘Well now, you are in a very representative position and you must make sure that you’ve handled yourself circumspectly. That you don’t embarrass other Black women.’ That was a heavy load, you know?”

Charlene Regester, author of “African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility,” said that Horne’s ability to negotiate the contract was in part the result of African Americans’ involvement in World War II. “They realized that because of the Black contributions, the country was changing. So they were gonna have to compromise in terms of the demands that Blacks were making and expecting in view of their contributions to the war effort,” said Regester.

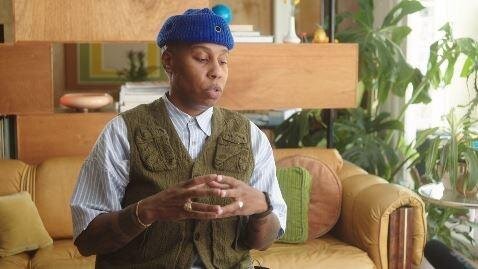

3. She refused to play a maid in any of her films

An important part of that contract was the caveat that Horne would not play servants, prostitutes, or other demeaning roles that were generally the only ones available to Black actresses at the time. Two years before Horne signed with MGM, Hattie McDaniel had been the first African American to win an Oscar for her role as “Mammy” in “Gone with the Wind.” “If you think about that iconic image of Hattie McDaniel kind of tying up the corset of Scarlett O’Hara, the Mammy is completely devoted to perpetuating white womanhood,” said author and cinema professor Jacqueline Stewart.

“For Lena Horne to say, ‘No, I will not play maids on screen,’ was to reject all of these deeply entrenched historical stereotypes of African American women,” said Ruth Feldstein, author of “How It Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement.” “She was saying, ‘No, I can be another kind of performer. I can offer a different kind of representation.'”

Horne said her refusal to play maid roles was somewhat controversial, and got her “into a lot of trouble” with other Black actors who feared that her actions could potentially further reduce film roles for African Americans and make it more difficult for Black performers to break into the industry.

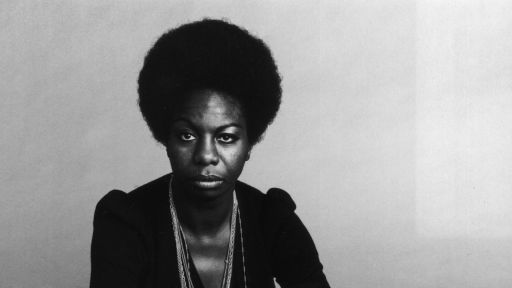

4. She refused to bow down to the industry’s skin color standards

Even as she set off on her trailblazing path, Horne continued to be criticized because of the color of her skin. As a Black woman with a lighter complexion, she was often accused of trying to “pass” as a white woman, which she strongly denied. In the early stages of her contract with MGM, the actor said that the studio put her in the film “Panama Hattie” and tried to pressured her into reinventing herself as a Latina. She refused.

“They said, ‘Why don’t you be Latin? Pass as Latin. I mean, you don’t look colored,’ and all that kind of nonsense,” said Horne. “The very fact that I was one of the first, you know, I was isolated right away because there was no niche for me. I was in the middle. Grey, this pale thing.”

The studio then tried to put dark makeup on Horne to “match the darker actors that I was working with,” she said, but it created a terrible contrast. Eventually, they brought in renowned makeup entrepreneur and inventor Max Factor, who created a brand new makeup tone called “Light Egyptian” especially for Horne.

Visibility as a Black woman and staying true to her culture was important to Horne, and yet she refused to be defined by expectations surrounding her race.

At the age of 80, Horne said during an interview: “My identity is very clear to me now. I am a Black woman. […] I no longer have to be a credit. I don’t have to be a symbol to anybody. I don’t have to be a first to anybody. I don’t have to be an imitation of a white woman that Hollywood sort of hoped I’d become. I’m me. And I’m like nobody else.”

5. She fought segregation in entertainment and beyond

Despite her level of fame, Horne only ever had two speaking roles, in the films “Cabin in the Sky” and “Stormy Weather.” The rest of the time, she appeared in films as a singer. This allowed Southern distributors and censors to cut her scenes out if they wanted to, without affecting the storyline.

“They hadn’t made me a maid, but they hadn’t made me into anything else either. So, I just became a little butterfly pinned up against the wall, singing all these lovely songs. Singing my heart away in Hollywood,” said Horne.

Frustrated and ostracized by a movie industry that was increasingly purging its associations with leftist entertainers during the McCarthy era, Horne returned to singing in nightclubs. In the late ’40s and ’50s, she fought segregation policies in the hotels and cities where she performed by insisting she and her musicians be allowed to stay wherever they performed instead of being relegated to Black neighborhoods in the area, as was the custom.

Horne also continued to fight racial and social injustices throughout her career, fundraising for groups like the NAACP and the National Council of Negro Women, and singing at civil rights rallies, including the March on Washington protest in 1963 where Martin Luther King gave his famed “I Have a Dream” speech.