Three dancers in striped costumes performing In The Upper Room. Passé position arms stretched. Photo: Twyla Tharp Foundation

Throughout her career, the dancer and choreographer Twyla Tharp has blazed a singular path that has shaped and reimagined the modern American dance scene as we know it today. Tharp seemingly draws from an endless well of creativity, often bringing together disparate elements from various types of movement, music, and art in each of the more than 160 works she has created and choreographed in her lifetime. With a Tony award, two Emmys, 19 honorary doctorates, a National Medal of Arts, and many more accolades under her belt, Tharp is indisputably a master of her craft. Here, we share some takeaways from the documentary Twyla Moves in which Tharp imparts some key creative lessons and tenets that have helped shape her life and career.

1) Just get out there and do it.

In the early ’60s while Tharp was studying at Barnard College, she was also taking dance classes at various studios around New York. The dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor had started a dance company that Tharp wanted to be part of. In true Twyla Tharp fashion, she marched into one of Taylor’s rehearsals one day, sat at the front of the room and told him, “My name is Twyla. I’m going to be dancing here.” Taylor was apparently so shocked, he let her stay.

Tharp admits that she wasn’t a very pleasant company member. She felt the work was not challenging enough, and so she told him.

“He just looked at me and said, ‘Well, maybe you better go out and try trial by fire,’ and I said, ‘”Okay,'” she recalled.

Soon, Tharp was out on her own, but quickly formed her own dance company that began performing in the park and any space they could find, including streets, building rooftops and art galleries, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tharp didn’t let physical space nor traditional frameworks limit her movement, but rather incorporated or merged her surroundings into her work.

“We were doing work that fit into spaces that were not stage spaces,” Tharp said. “Stages were for ballet companies, I was not in that tradition. I was in the tradition of ‘just get out there and do it.'”

2) Sometimes less is more.

Tharp’s first publicly performed piece of choreography in 1965 was called “Tank Dive” — a play on the improbable nature of finding success and notoriety as a dancer. She equated the chances of success to “about the same as somebody jumping off a 100-foot pole into a thimble of water.” And so the name “Tank Dive” was born.

In “Tank Dive,” Tharp was already beginning to innovate by doing things that “nobody else was doing,” such as, “standing still on relevé for a minute and a half.” She also stripped the piece back to its raw elements, with a conscious decision to omit music.

“What I needed to learn was ‘what could movement communicate [without music]?’,” said Tharp. “Because if I do a phrase to happy music, everybody will be happy. If I do the same phrase to sad [music], they’ll all be sad. What if I just do the phrase? What will they feel?”

“And it did what it was supposed to do, it launched a career,” she said. “Like the diving board that you use to dive down into the water, and then you gotta learn how to swim.”

Tharp didn’t use any music in any of her pieces over the next five years.

3) Breaking boundaries and reinvention is key.

Tharp returned to New York after a short break from dancing, during which time she moved to a farm with her husband and gave birth to her son, Jesse. She began building dances with her troupe that would appeal to a broader audience, as well as provide an income.

“We used to be in the avant-garde, ragged hair hanging down however, blue jeans are torn. So on and so forth,” she said. “We started realizing if we are going to become a commercially viable entity we have to put on a show. And it was suggested that our hair needed to have attention.”

The dancing evolved and so did the look. Tharp decided to cut her hair into a floppy bob. She adopted jazz music into her routines as well as elements of humor and comedy. She even took on one role as a dancing silent clown.

“It was a sort of progression from austere kind of in-silence pieces to showbiz pieces. Show the folks a good time,” she said. “Those early pieces were kind of tribute pieces to American theatrics.”

The desire to break boundaries — both creatively and socially — was an important aspect of Tharp’s work.

“I didn’t wanna be stopped by any of the sort of clichés about what women could do or couldn’t do,” she said. “In vaudeville, women did not do the stuff Buster Keaton did. So, I said, ‘Well, I can do that stuff. Okay, guys can do it. I can do a sprat fall.'”

The desire to reinvent the wheel never left Tharp. In 2020, she imparted some wisdom to the Russian ballet dancer Maria Khoreva on breaking from convention, telling the younger dancer:

“Keep your technique for your whole career. It’s beautiful. Don’t ever lose it, but learn how to work around it. You pass through academically correct and go somewhere else with it and come back to it.”

4) Blend the old with the new.

In the early ’70s, Tharp began blending modern dance and ballet in a unique way into her pieces. This caught the attention of Robert Joffrey, who invited Tharp and her modern dance company to fuse with his classically trained company.

“Deuce Coupe” turned out to be a piece about the vitality and spirit of adventure of teenagers, and Tharp took this merging of styles one step further by choreographing it to music by the Beach Boys.

“I thought that the Joffrey Ballet audience wanted something with energy and something that was fresh. And the Beach Boys had a vitality and a let’s-get-going-ness here,” said Tharp. “All their songs are about motion.”

The scenic design was equally as fresh. Tharp hired graffiti artists to spray paint the perfect background for the ballet at a time when graffiti was illegal, but omnipresent everywhere on the streets of New York.

“[The artists] were wanted by the police. We had to lock them up upstairs so that they wouldn’t get arrested between shows. They were outlaws,” she recalled.

On the heels of her success with “Deuce Coupe,” Tharp was asked to choreograph a dance for Russian ballet superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov — “Arguably the greatest dancer in the world,” she said.

“Baryshnikov had just come to this country and he was displaced,” Tharp said. “He’s Russian, classically trained. I’m from the Midwest, modern dancer. You could not have found more disparate elements to try to gather together.”

Tharp worked through enormous expectation and pressure to create what she described as “lightning in a bottle.” It was the beginning of many more partnerships between the Midwestern modern dancer and the classically trained ballet master.

5) Know what you want and work hard to get it.

After initially choreographing silent pieces in the early days, Tharp’s return to sound and movement was a triumph.

“During the course of my career, I’ve used many different kinds of music. Every kind of music that moves me, I use it, whether it’s pop, whether it’s classical, whether it’s jazz, whether it’s historic,” she said. “I grew up totally exposed to music, practicing it, hearing it, loving it, living in it. So, having spent five years dancing with no music, I felt that I understood that, and then I could use anything.”

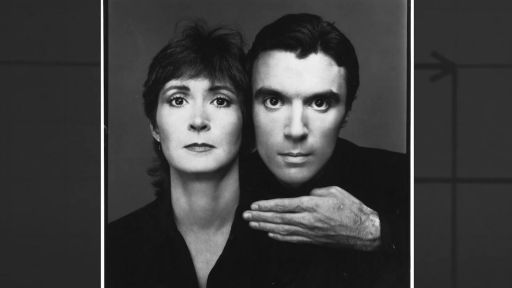

In the late 70s, Tharp choreographed the anti-war musical feature film “Hair.” She later also partnered with composers and musicians such as Philip Glass, David Byrne and Billy Joel, who worked with Tharp on the Broadway show “Movin’ Out.”

“She had a vision in her head about what she wanted. It was so intense, it was something I couldn’t say no to,” recalled Joel. “A lot of energy in a small woman, almost intimidating. And I thought, ‘Oh, this is somebody who is — you don’t wanna get in the way’ … And that’s how the collaboration worked. I pretty much stayed out of the way and she ran it.”

Byrne recalled that Tharp pushed the dancers physically very hard — sometimes to their limits — and then pushed them further to see if they could go further.

“In the same way she was driving the dancers, she was driving me, kind of pushing me to raise the level of what I had done. We got to about a little over an hour’s worth of material, and she’s asking for more, and then more, and then more,” he said. “I’d never had anyone push me like that before. Turned out to be really good for me.”

6) Don’t spread yourself too thin. You can’t be everything for everyone.

In the early ’80s, Tharp’s career was crescendoing at a dizzying pace. She was touring around America and the world, running a business, and partnering with many collaborators from across the musical, art, and dance worlds. It was starting to take its toll.

“In order to support this mechanism we were doing a very large number of fundraising events, galas, photo shoots, federal subsidies, state subsidy, patronage. We were touring 150 shows a year over the world,” she said. “I was very fragmented. … Jesse was becoming further distant as I’m bouncing around here. I was being very, very distracted from myself. I was going to have to stop working the way I was because this could not be sustained.”

On top of that, Tharp says that her level of fame actually began stifling the creative process for her.

“It is the irony of success. They want you to look like what they think you ought to look like and it becomes about repetition rather than trying new things,” she said. “There was no time left to make dances or to work in the studio with dancers to evolve.”

“The result of that period, and it should be fine to say, that I broke down,” she said. “You wanna be everything for everyone. You can’t.”

7) Redefine what’s possible. The only way out is forward.

When the realities of the Covid-19 pandemic set in and the world of dance shut down in 2020, Tharp immediately began to devise opportunities to create connections between dancers and keep working through quarantine. She choreographed a Zoom piece “in two dimensions and four squares.”

“The pandemic totally closed the opportunities for dancers to work, dances to get made, dances to get presented,” said Tharp. “Maybe I can connect a dancer with another dancer through Zoom and we can create a single thing and we can pull this together even though we’re miles apart.”

“Even in this stage of her career and her life she’s setting the standard for where dance is evolving to,” said Misty Copeland, who was one of the dancers participating in the virtual dance piece.

“Whenever I see Twyla’s name come up on my phone I’m just like, ‘I don’t know what to expect. But I know it’s gonna be exciting’,” said Copeland.

“Dancers give me their hopes and their dreams. And together we work to redefine what is possible, for they will find unimaginable solutions to my dilemmas,” Tharp said. “All dancers know that there is only one way out — and that is forward.”