Claudia “Ladybird” Johnson once said, “art is the window to man’s soul. Without it, he would never be able to see beyond his immediate world, nor could the world see the man within.”

Much of American culture has been shaped by its art – but how might our world be different today if the literature, films, and music that have defined generations of Americans never even saw the light of day? Here are nine of the most iconic American masterworks that were almost never made.

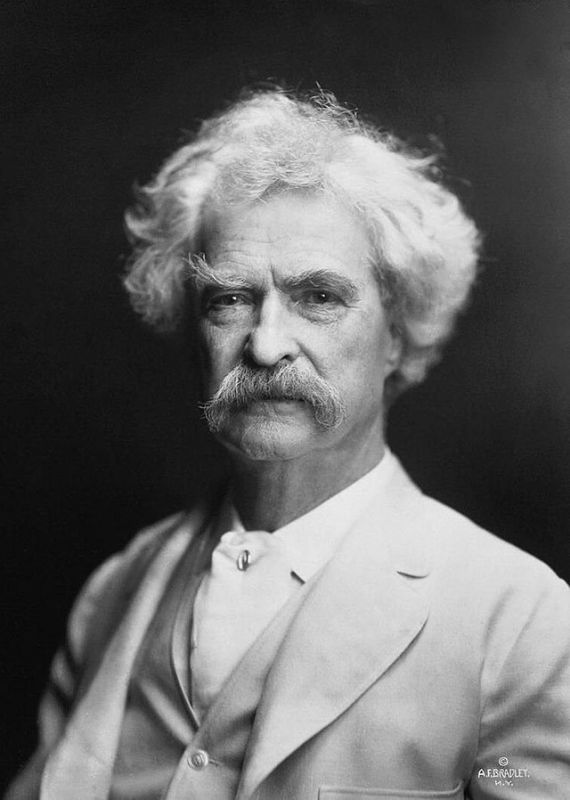

1. “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain

Following the tremendous success of “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” Mark Twain began to pen a sequel starring Tom’s rugged best friend, Huck. The story was meant to be in a similar vein to its predecessor: a thrilling adventure book for children without much complexity. In the midst of writing the sequel, however, Twain took a three year hiatus, during which he embarked on a river cruise down the Mississippi River. No one is sure what exactly Twain may have witnessed on this journey, but when he returned to his manuscript afterward, the book transformed from an uncomplicated children’s book into a charged commentary on slavery, segregation and racial identity. He took yet another three year hiatus before finally completing the book nearly a decade after he started it in 1876.

2. “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

Harper Lee was 31 years old when she took her first draft of “To Kill a Mockingbird” – then called “Go Set a Watchmen” – to publishers at the now-defunct JB Lippincott Company in 1957. Editor Tay Hohoff was impressed with the read, but felt it was not yet ready for publication. She pushed Lee through revision after revision – and Lee became more and more frustrated as the taxing cycle of writing and rewriting moved slowly along. One particularly draining winter night, a fed up Lee tossed the entire manuscript out of her window. It landed in the snow. Lee called Hohoff in tears, ready to give up on the book entirely, but Hohoff persuaded her to run outside and pick up the pages before they were completely ruined. Lee begrudgingly rescued her draft – and not long after, the final draft of the book was published under the new title “To Kill a Mockingbird.“

3. “Carrie” by Stephen King

“Carrie” is Stephen King’s first published novel – and arguably his most popular. Still, King was never particularly attached to “Carrie” – going as far as to throw the first three pages of the story in the trash. In “On Writing,” King wrote that he “never got to like Carrie White.” He told Playboy Magazine that he felt the whole book was “clumsy” and “artless.” He was working as an English teacher when he first started writing it and had only received authorial success through short story publications in magazines. He believed Carrie White’s story was too complex to squeeze into a short story, and decided to trash it. Afterward, his wife Tabitha discovered the pages in the trash can and recovered them. She believed there was something worth saving in the story and encouraged King to continue writing it. He did, and soon he was armed with the novel that would launch him into stardom.

4. “Little Women” by Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott was not particularly interested in stories about women – at least not typical women – so when a publisher asked her to write a “girl’s story,” her stomach filled with dread. Alcott had a fierce and rebellious spirit. She was already a published author under the pen name A.M. Bernard, and she wrote primarily mysteries and short stories about strong women who did not confide to societal norms. She cautiously agreed to try to write a story for and about the average American woman, deciding to base the story on the experiences of herself and her sisters, because she “never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters.” Alcott found the work dreadfully boring and was ready to give up, when a test group of girls read the start of the first draft and became enthralled with it. With that encouragement, she finished “Little Women” and published it. Eventually, she returned to writing stories she was more interested in, admitting in her journal that she was “tired of providing moral pap for the young.”

5. “Rent” by Jonathan Larson

Jon Larson was working as a waiter at the Moondance Diner in SoHo when he conceived of the idea of “Rent.” His most recent musical, “Superbia,” had received relative praise at its workshop in downtown New York City, but no one wanted to produce it. Producers found the story too depressing – musicals were meant to be uplifting. Larson was ready to quit writing musicals altogether, exhausted by the bitter rejection that followed years of hard work. During this time, Billy Aronson, a friend and fellow playwright, approached Larson with the idea for a bohemian style musical set in New York City. Larson fell in love with the idea and his passion was reawakened. He and Aronson, however, disagreed on their respective visions for the musical, and they made little headway on the book and lyrics. Eventually, Aronson left the project and gave Larson permission to pursue it on his own. Larson did, and the devastating and empowering musical “Rent” was finally born.

6. “Take the ‘A’ Train” performed by Duke Ellington and written by Billy Strayhorn

“Take the ‘A’ Train” was Duke Ellington‘s signature anthem – the opening track to nearly all of his bands’ performances. It’s the sound most associated with Ellington’s name, although its most famous cover by Ella Fitzgerald is perhaps even more iconic. Today the tune is beloved and familiar, but it was almost never written in the first place. The song was originally composed by Billy Strayhorn, a teenager who Ellington hired to compose songs when Ellington himself was too wrapped up to begin any new tracks on his own. Legend has it that Strayhorn thought of the song while attending a party, and scrambled to write down the lyrics, before deciding it felt derivative and tossing it in the trash can. Ellington’s son discovered it there and resurrected it. The song was brought to life and quickly became a smash hit.

7. “What’s Goin’ On” by Marvin Gaye

Marvin Gaye had to put up a fight for his label to release “What’s Goin’ On” – both the title single and the album. It was a big shift from Gaye’s previous assembly line love songs, which had made him famous. Gaye was at a crossroads in his personal life and career and was no longer interested in writing love songs. Gaye’s brother had recently returned from Vietnam a different person – his entire personality seemed tainted and damaged. At the same time, Gaye’s marriage was faltering and he was grieving the loss of Tammi Terrell, his beloved duet partner. While facing so much tragedy in his personal life, he also found himself becoming absorbed by the harrowing global and national headlines – from the shootings at Kent State to the Vietnam War to the rising poverty levels. He wanted to create something that mattered – that spoke to the state of the world he found himself in. His label, however, had no interest in risking the big profits that came from Gaye’s original sound, and refused to release “What’s Goin’ On” until Gaye threatened never to record with them again if they didn’t. The glaring success of Gaye’s album and single proved that this was one risk worth taking.

8. “Like a Rolling Stone” by Bob Dylan

“Like a Rolling Stone” is considered by many to be the greatest song of all time – influencing an entire generation of rock stars, including Bruce Springsteen (who said the song inspired him to “take on the whole world” through his music). Before the iconic song was recorded and released, though, Dylan compared it to “vomit.” He wrote it in a long, dizzying draft while touring around Europe, but claimed that “when I got to the jugglers and the chrome horse and the princess on the steeple, it all just about got to be too much.” He finally finished the piece and recorded eleven versions that were each deemed “unusable” because Dylan was singing so fast that the instruments couldn’t keep up. They finally mastered the sound and the song was released to near instant success.

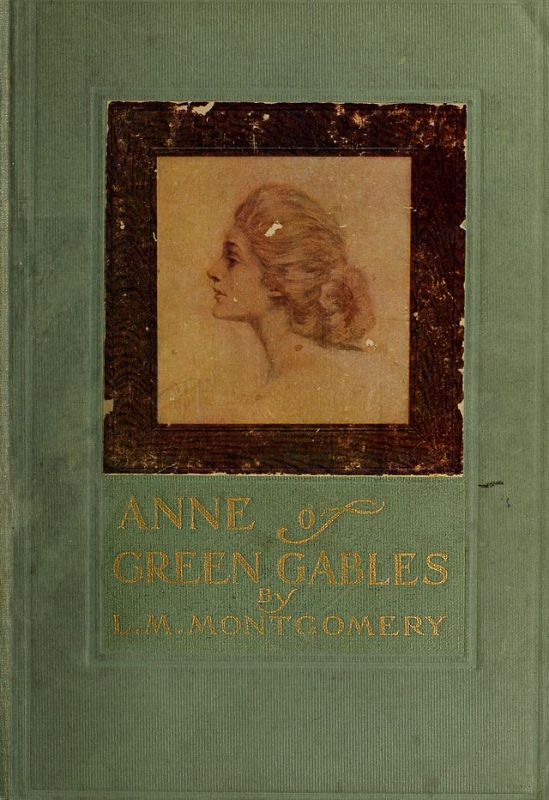

9. “Anne of Green Gables” by L.M. Montgomery

When L.M. Montgomery first envisioned a little orphan girl named Anne, she was planning to write a series of short stories to be published in the Sunday paper. After beginning to write, however, she fell in love with the big-hearted character, her adoptive parents, and her little town of Green Gables. She decided to devote an entire novel to Anne instead. Montgomery considered “Anne of Green Gables” to be a “labor of love” and the most enjoyable story she had ever written. She eagerly sent the draft to publisher after publisher, just to be rejected over and over again. Montgomery later wrote in her diary that after the fourth or fifth rejection she “put ‘Anne’ away in an old hat box in the clothes room.” Montgomery forgot about the book for a year, until she was rummaging for winter clothes and rediscovered it in its hiding place. She decided to send it out one last time – and this time, a publisher finally bit.

Bibliography: