It wasn’t the first time I had seen Twyla at work with her dancers, but it was definitely the most memorable. She was deep into the piece that would become “In the Upper Room” (1987), a vast and thrilling spectacle that juxtaposes ballet with Twyla’s own movement style – not to emphasize the differences but to display each at a peak of power, with both sets of dancers working in constant interchange as they surge through mists towards what might be heaven. But all that splendor was far in the future; today was the nuts and bolts of making choreography. When I got to the studio I found Twyla hobbling around waving a fistful of carrot sticks. She was hobbling because she had pulled on a sweatshirt over her tights, jamming her legs into the sleeves as if it were a pair of pants. There was no rationale here; she had found a heap of discarded practice clothes and this particular improvisation had struck her fancy. “Don’t try to rush this phrase,” she told the three male dancers who were sweating in the middle of the floor and listening to her intently. (They had no choice but to listen intently – she was stuffing carrots into her mouth as she rattled along.) “It’s never going to go fast. It’s always going to be a crude, awkward phrase. That’s why I gave it to you. It has no sense of humor, no sense of humor. No sense of story, no sense of story. No sense of pleasure, no sense of pleasure. Got that?”

“Yeah, at least eight times for some of it.”

The phrase began with a huge, abrupt jump, then barreled into an athletic spree: two of the dancers were working more or less in unison and the third was doing the same movement in reverse. But I barely noticed the structure: what was happening was simply raw vigor, an abstraction of physical power itself. The score, commissioned from Philip Glass, raced along in cascades of repetition without perceptible landmarks. For dancers it must have been like working on a moving sidewalk.

Finally she jumped up. “Lemme see our little tap phrase from the other day. What is the phrase? Da yump, da yump, da yump.” They switched to the tap phrase, while she watched with her arms crossed. The carrots had been demolished, replaced by a clutch of celery sticks. Absorbed in the men’s trio, she jammed the last celery stick into the waistband of her tights and forgot about it. “Try this for me: Keep the arms behind the back one time. Awright, we’ll do it that way, using the back like that. You don’t want people to say, ‘Oh how cute, a tap dance here.’ You want them to think, ‘Gee, I never realized how appropriate a tap dance would be here.'” Sure enough, on the rolling and repeating chords of the Glass, their dry little tap dance was riding as easily as foam on waves.

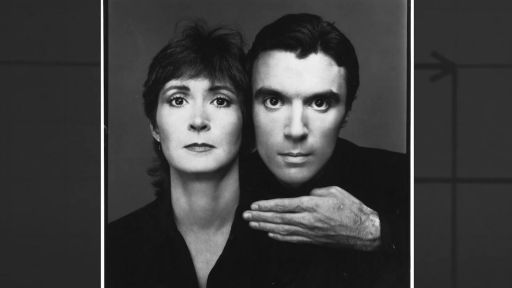

Twyla had invited me to watch her create this piece because the two of us were thinking of doing a book together about her work. As a dance critic, I’d been reviewing her performances for years, but here was an opportunity to probe the actual mechanics of mind, body, and imagination that drove her choreography. For months I made regular visits to the studio, and every couple of weeks I would go over to her apartment with a tape recorder and interview her. That part was no picnic, at least at first. Twyla’s small talk generally consisted of “Okay, come in,” followed by “Now what?” Her response to dumb questions, which I seemed to ask constantly, was a look of polite disbelief. Nowadays she’s a lot more civilized in social situations, but back then I always had the feeling that she expected me to perch right inside her head and chat directly with her brain. I decided, for my own sanity, to pretend the woman sitting across from me was a figment of my imagination – someone possessed with every quality you want in the person you’re interviewing, including brilliance, humor, intuition, generosity, and a willingness to take delight in almost anything. The choreography was certainly like that. How could Twyla herself be any different? And of course what I learned was that she wasn’t any different – she was just keeping all the doors closed until I figured out how to open them.

The book project never came off, but spending those months with Twyla became the most exhilarating experience of my life as a critic. We talked and talked, she worked and worked. Twyla has a number of patron saints – Mozart is one, Buster Keaton is another – whom she apparently keeps on retainer. Whenever she paused a rehearsal to scrutinize a bit of partnering, or to listen to a few bars of music, I could practically see the saints hovering around her with suggestions. Then she’d ask the dancers to try something different – often something impossible – and as they grappled with solutions, a new phrase would break forth. Later on, when I saw “In the Upper Room” in the theater for the first time, I realized that every single thing that had happened in the studio, including all the mishaps and discarded ideas, had helped to propel the 39 glorious minutes unfolding in front of me. Nothing had been wasted – though much of it was now invisible, including the carrot sticks.