I topple sideways out of a turn and slink back to where I began. “Ugh, I’m just so tense,” I whine. “My neck.”

“Well,” comes Twyla’s dry virtual reply, “relax.” And she waits in impatient silence for my next attempt.

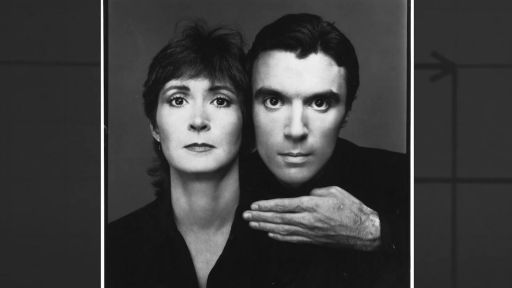

I retired from dancing long before the pandemic forced most of the arts into hiatus. And since my brief and spectacularly dense chapter spent touring with Twyla’s company for her extensive 50th Anniversary festivities, we’ve remained mostly estranged. Still, in the first few weeks of quarantine I feel compelled to reach out to her, admittedly more curious than I am concerned.

“For me, it is always about the water going under, over, around, through the f—–g rock,” she offers in cryptic response to my note.

Within a week, Twyla and I are at work, and by midsummer we’re hours of Zoom meetings into our reconstruction of her iconic “The One Hundreds,” a 1970 masterpiece filled with all of the exploratory, volcanic energy of a young Tharp on the brink. Comprised of 100 11-second phrases and performed first in silent unison by two dancers, next by five dancers completing 20 each, and finally by 100 volunteers simultaneously dancing one phrase, its choreography is laced with a subtly confrontational pedestrian vernacular that epitomizes her rebellious, career-long commitment to finding dance in any movement and in many bodies.

The opening duet offers the dancer’s perfect mental and physical tour de force: a public challenge to recall each phrase in sequence, referencing everything from ballet to baseball while spinning through its complexity as if creating it on the spot. The piece requires exquisite technique and formidable stamina to underpin the trademark Twyla nonchalance so many of us can only aspire to emulate, and remains a comprehensive lesson in the exhilarating, exhausting impossibility of her choreography.

“I don’t think movement should be compromised for the sake of the dancer,” she’ll say, and then weave aggressively fast footwork into agonizingly slow adagio before asking you to reverse your movement as if rewinding yourself on an old VCR. She’ll then reset the whole thing hurtling backwards down the diagonal, demanding the rigorous clarity of your balletic roots as she directs you to mime twirling a baton while channeling James Dean.

“Are you having fun?” And she’ll grin and wait for your “yes.”

Lately, it’s a “no” for me. I hunch close to my computer screen to watch her fold her nimble septuagenarian frame into a yogic approximation, nostalgic for the days my now untrained body felt more affinity for her work. I know when Twyla asks after my daily push-up routine that my apartment’s limitations disguise none of my current weaknesses. Still, Twyla has always been a much better friend than I have to the great dancer in me. Today, and any day, we’ll work until we bring her forward.

Twyla’s initial rehearsal terms are deceptively simple: be punctual (and be warned that her clock consistently runs five minutes fast), bring all the tools of your training, and attack the physical and intellectual rigor of her rehearsals with a curious and open mind.

Or, as she’d put it, “show up every day and do the work.”

As I learned when I danced with her company, eventually she’ll require everything, but she’ll give her dancers even more. First into the studio every morning following her devout attention to her own daily exercises, she greets each dancer in turn with new stakes – a new character or a new metaphor or a new catastrophe – that today’s dancing is tasked with solving. She’s in our flushed faces immediately following the first (and second, and third, and fourth) difficult run of one of her dances, ignoring the obvious technical flaws she trusts we’ll fix and instead evoking the grandiose imagery of the hero or villain we must better conjure.

Meanwhile, she’s by our side on the bus to every tour stop. She’s knocking on the dressing room door to borrow a little lip gloss. She’s backstage warming up with us as we wait for our call to places in the auditorium’s wings.

And now she’s on my laptop, traversing the pandemic’s forced distance with her customary cackle as I repeatedly try and fail to execute to her satisfaction what should be an easy, somewhat improvised shrug. “Kaitlynski, you don’t have to do it again, but tell your students I want them to give me a good Gen-Z ‘whatever’ there.” She follows with a little off-the-cuff brilliance on the subtle difference between acting cool and being cool, offering a humorless reminder that I should be taking notes on everything she says.

A year into quarantine, I’m sharing “The One Hundreds” with the dancers at Marymount Manhattan College. We’ve managed to stage a version without ever meeting, some students learning from their homes or dorm rooms, some masked and separated in the studio according to dance’s new normal. I’m frequently hurtling myself across the floor of my Brooklyn one-bedroom, looming large on my tiny screen in a mere approximation of the phrases I ask my students to fully embody. But their next try is much improved, and the following even better. I relish for my students that familiar sense of achievement and self-confidence borne of an earnest willingness to wrestle with this movement’s superhuman expectations.

Twyla believes adamantly in her dancers. In return, she asks only that you believe just as determinedly in her dances.

My students are stuck on the last count of one phrase, so I jump in. “It’s just a shrug. Like… a whatever. Twyla says be Gen-Z.” I’ve lost her lecture on cool somewhere in my iPhone notes, so my feedback today and always offers only some of her pith with little of her accompanying profundity.

They get it anyway, and soon we’re laughing and comparing our weirdest generationally-inspired shrugs.

“Are you having fun?” I grin and wait for their “yes.”