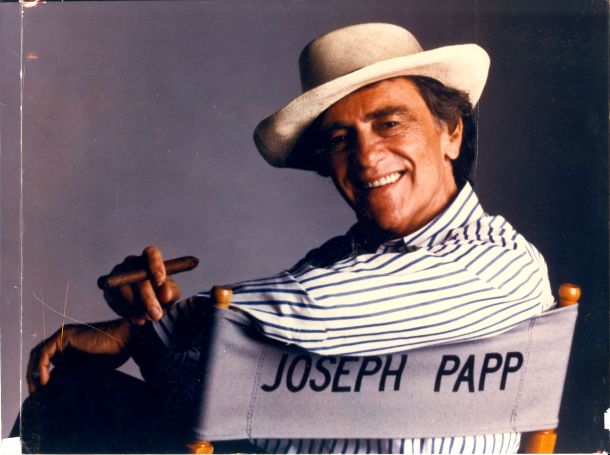

Los Angeles Times theater critic Charles McNulty recalls his time as an intern at The Public Theater under the indomitable Joe Papp, reflecting on the 1989-1990 season amidst the AIDS crisis and Papp’s final years.

Early in my career, long before I had any inkling that I would become a drama critic, I had the privilege of being a fly on the wall at the center of the theatrical universe.

At the time, I was pursuing a master’s degree in playwriting and dramatic literature at NYU. I talked the literary department of Joseph Papp’s Public Theater into offering me an internship for course credit. My apprenticeship was supposed to last for one semester, but I didn’t want to leave and—knowing they had a mountain of unsolicited plays to review—I offered my services as a part-time script reader.

The literary office, under the auspices of Gail Merrifield Papp (Papp’s wife), flowed directly into the boss’s headquarters, giving me a front-row seat to the comings and goings of the 1989-1990 season. (In the summer of 1990, bearing a letter signed by Papp himself, I left The Public to continue my studies at the Yale School of Drama.)

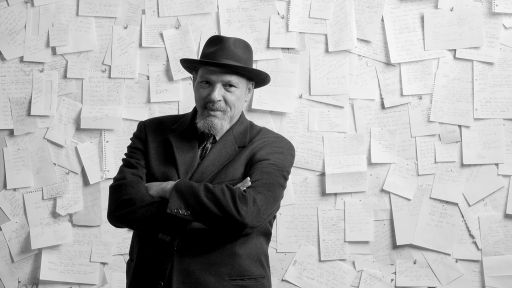

Papp, the founder of the New York Shakespeare Festival, was in his twilight years. He was already grooming his successors, though he vowed that he wasn’t giving up the ship. He was too busy contending with budgetary emergencies, leading the charge against Senator Jesse Helms’s campaign to restrict NEA money on “obscenity grounds” and decrying the make-or-break power of The New York Times’s culture pages.

His death in 1991 wasn’t far off, but he had no intention of going gentle into that good night.

As he was undergoing cancer treatment, his son Tony was confronting his AIDS diagnosis. Silence equals death was the rallying cry of the city, and Papp knew there wasn’t a moment to spare when it came to securing the future of his politically outspoken, communally inclusive theater.

As a young gay man who had seen Larry Kramer’s “The Normal Heart” at The Public while my uncle was dying from AIDS, I shared this dire sense of mission. It was through my work at NYU AIDS Projects, a center for education and training for healthcare professionals, that I was able to go back to school tuition-free. Activism and theater, emanating from the same caring source, were inextricable for me. This confluence of interests is no doubt what prompted Jason Fogelson, The Public’s compassionate literary manager, to cobble together an internship for me.

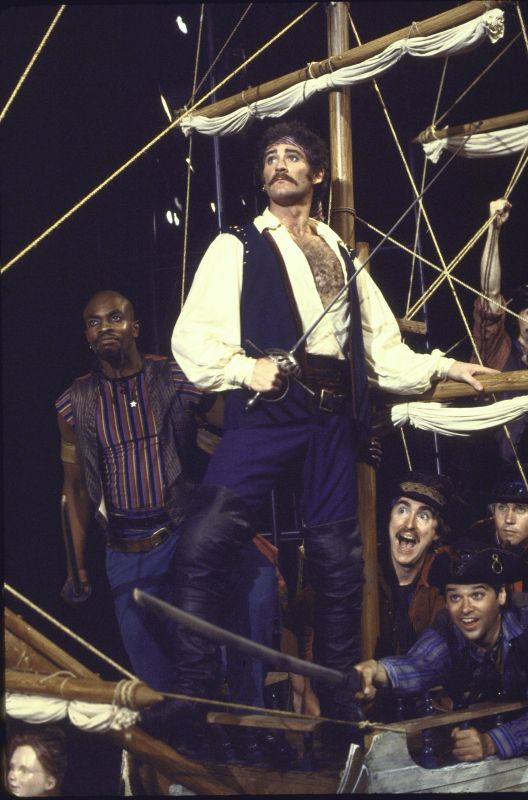

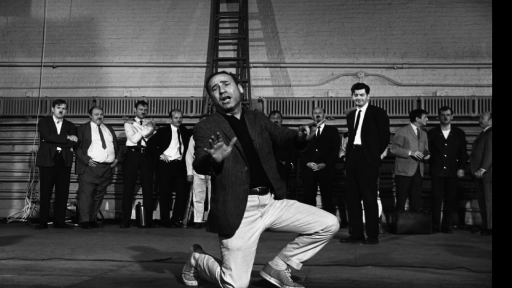

Production of “Twelfth Night“ in 1989. Photo by Martha Swope © The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

I knew that Papp was in his final act, but it wasn’t until he appointed JoAnne Akalaitis as artistic associate and (in a show of remarkable acumen) George C. Wolfe, Michael Greif and David Greenspan as resident directors that I realized how near the end he really was. But when I began in 1989, Papp was still throwing lightning bolts à la Zeus.

King Lear may be the more apt comparison, as many observers began to see him as a wrathful, stumbling monarch railing against any encroachment of his theatrical sovereignty. As an intern, I never bore the brunt of his notorious temper. But his larger-than-life, rough-and-tumble New York personality—something I was completely at home with as a fellow Brooklyn native—informed every aspect of The Public Theater’s identity.

Buffering him at work was a makeshift family that radiated all the loyalty and frustration, love and rage that families are known for. Associate producer Jason Steven Cohen was his right-hand man; legendary casting director Rosemary Tischler was an invaluable artistic consigliere; press director Richard Kornberg provided watchdog protection.

Barbara Carroll, Papp’s executive assistant who stood sentinel outside his office, called him “chief” in the same cadence of Jimmy Olsen on “Adventures of Superman.” Emmett Foster, an actor and performance artist who served as personal assistant, shuttled him around with the discreet tenderness of Edgar (of “King Lear”) guiding his hobbled father through a terrain of trouble.

When Papp would enter the artistic offices on Lafayette Street, the entire staff would spring into military readiness. His energy was unstoppable, his authority incontrovertible, his commands irrevocable. Slunk in my chair, my face buried in a script, I would sometimes find him hovering over me, inquiring about the quality of the hopeless play I was dutifully skimming.

A former stage manager, he enjoyed checking in on the small details of his operation. He wanted to know how many scripts I had read that day and was impressed that I had beaten his daily average when he was a script reader. I couldn’t believe that he even noticed me, never mind that he wanted to hear what I thought. But he was a democratic autocrat, with deep plebeian sympathies.

His afternoon appearances in the office usually augured an important meeting. Harry Belafonte arrived one day for a tête-à-tête that everyone but me seemed to think was perfectly routine. Tracey Ullman turned up to discuss her casting in “The Taming of the Shrew” in a summer Free Shakespeare in the Park production that seemed like something I might have dreamed into existence.

The Public was a magnet for divergent talents, artistic, intellectual and managerial. Kevin Kline was hard at work on “Hamlet,” dissecting the text line by line with Barry Edelstein, who fresh out of Oxford where he studied Shakespeare on a Rhodes Scholarship, would humor my half-baked theories on the fate of playwriting after Samuel Beckett.

Raul Juliá was doing his mighty best to ground Richard Jordan’s flighty production of “Macbeth” with gravitas. Wolfe, adapting and directing “Spunk: Three Tales by Zora Neale Hurston,” was refining the theatrical alchemy that would eventually earn him the keys to the NYSF kingdom.

Tom Ross, The Public’s co-director of play and musical development, was collaborating with rock great Todd Rundgren on “Up Against It,” a musical spun from a Joe Orton screenplay. Getting my friends into a private party for the show may have boosted my social capital in New York more than anything I’ve done since.

There were many occasions for an underling to be star struck, but I was especially giddy when playwrights were in the house. I never did get to meet my hero Caryl Churchill when “Ice Cream with Hot Fudge” was on the bill. But another major British dramatist, David Hare, made himself at home in the artistic offices when his play “The Secret Rapture,” a pointed parable of Britain under Margaret Thatcher, was in rehearsals.

Hare couldn’t resist engaging a literary drudge on what he was reading. He wanted to know what the ideas were that were driving the play, and though I recall being acutely tongue-tied in my response, I now realize that he was quietly educating me on where value might lie.

After a short run at The Public, “The Secret Rapture” opened on Broadway, where it was met with a stinging review by Frank Rich, The New York Times’s all-powerful theater critic. Aware that this spelled doom for the production, Papp and Hare were huddled in a conference downtown when war was declared against The New York Times.

Hare fired off a blistering letter to the offending critic. Papp stormed out of his office and insisted that we take this battle into the streets. He enlisted me to pass out leaflets outside the theater to bring awareness to this urgent cultural problem. “Yes, chief!” I gulped, with red-faced obedience. (Today I’d be assigned the easier task of launching a “tweetstorm.”)

This melee over “The Secret Rapture” inspired the legendary Variety headline: “Ruffled Hare Airs Rich Bitch.” Oh, but what extraordinary luck for a future critic to be in the room where it happened! I witnessed firsthand the effect of criticism on artists who were struggling, however fallibly, to make work that mattered.

Joe Papp had one of the biggest Broadway triumphs of all time in “A Chorus Line,” but he funneled the proceeds to The Public where playwrights and directors could be sustained over the long haul. Off-Broadway, formed in opposition to the commercial theater, was where real work was forged. It was where Shakespeare was renewed and new writing reflecting the cultural richness of New York was born.

For decades, Papp was the pugnacious lord of this realm, fighting, to keep this art form alive and accessible to all. The quality of the work was variable, but institutional success wasn’t measured in hits and flops. The goal was to extend opportunities for artists and audiences to come together to meaningfully engage what was going on in their lives.

Papp’s legacy lives on, not only in the flourishing theater he created, but also in the countless artists, producers and even odd critic he helped shape with the force of his personality and the fervor of his defiant values.