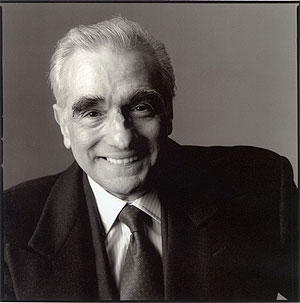

Martin Scorsese

Kent Jones: We started this movie half a decade ago.

Martin Scorsese: We started talking about it a year or so after Kazan passed away. I wanted to make something that honored him and his place in my life and my approach to the work, but that was also honest, that reflected his honesty about himself, and I asked you to work on it with me.

KJ: You wanted to be able to express what you couldn’t express to him when he was alive…

MS: Which eventually became part of the subject of the movie.

KJ: Yes. It had to be.

MS: Exactly.

KJ: It started off as a very different kind of project.

MS: We were going to do interviews. And then it seemed like the right idea to go in a different direction.

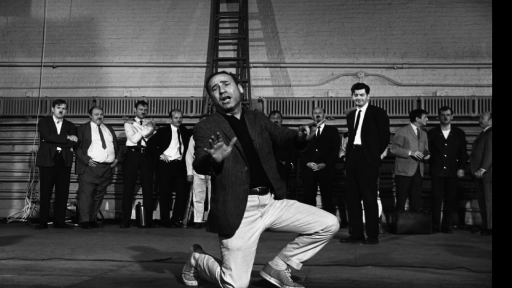

KJ: There’s a very good film to be made about Kazan as a person, as the man who started with the Group Theatre, who acted in Waiting for Lefty, who went on to revolutionize Broadway, then started the Actors’ Studio, then became a friendly witness before HUAC and suffered the consequences, then made a string of great films, changed the face of acting in theater and movies, suffered through the trauma of his first wife’s death, reinvented himself as a writer, and so on. It would be a real epic. But that felt like someone else’s idea.

MS: The thing was to convey something about the relationship, and by that I mean my relationship to the films, and that meant going back to the way that I received them when I saw them as an adolescent.

KJ: And the distinction between your relationship with the films and your relationship with the man, and the way you saw the films when you were young and the way you see them now.

MS: Right.

KJ: I thought that was really interesting, because it doesn’t have anything to do with film aesthetics or official history. Actually, in a sense, it does – it’s the way you receive films when you’re young and wide open to them.

MS: Yes. You don’t know how it’s done or why, you just know that the picture is speaking to you and addressing something that can’t be addressed in your life, by anyone you know, because it’s private, embarrassing. You’re young and figuring out who you are in relation to everyone around you, the adult world around you, but you’re not on the adult wavelength yet.

KJ: Or maybe you don’t want to be, and it’s about finding a way to talk to yourself.

MS: Yes. Which is what a psychoanalyst is supposed to help you do.

KJ: But when you’re a kid, you’re trying to do it yourself. You need to. It does remind me of something Andrew Sarris said, that if you want to psychoanalyze someone, just ask them about the movies they’ve seen.

MS: I wouldn’t know where to start there. I’ve seen so many. So have you.

KJ: I received your movies in the way you’re describing when I was a little older, when I was 16, 17.

MS: And I was 12 and 13 when I saw On the Waterfront and East of Eden.

KJ: You weren’t really aware of the Actors’ Studio or HUAC or any of that when you were young, were you?

MS: Not at all. Of course, we knew about the red scare in general and the blacklist, we knew about the Army-McCarthy hearings, the Rosenberg case. But Kazan’s testimony and the reaction to it we never heard of. And the Actors’ Studio? Another world.

KJ: We talked quite a bit about HUAC and how to deal with that.

MS: I didn’t want to make a movie about the blacklist. It’s been done and done well.

KJ: The issue is: how do you talk about Kazan? Because, of course, you can’t not talk about his friendly testimony. But it’s just as important to not let his testimony overshadow everything else. I was fascinated by his autobiography, the way he circled around the topic over and over again – apologizing for it in a dream, rationalizing it, raking himself over the coals for it, moving past it, returning to it. It was completely unresolved.

MS: The important thing was to not judge him on the one hand, and to not lecture anyone on the other hand.

KJ: And obviously neither of us wanted to condemn him. I think it’s so strange when people do that, and then his movies along with him.

MS: The movies?

KJ: Sure. Like, “He was an informer so his movies were worthless.” I’ve read it over and over again. I always feel like asking them, “So you’re not going to watch Wild River because Kazan named names? Or East of Eden? Or Splendor in the Grass? They’re all bad a priori? Along with Celine’s novels, Ezra Pound’s poetry, and Heidegger’s writings, I guess.” And how about Robert Rossen? He named names, so I guess he’s out too. And Clifford Odets and Burl Ives and Jerome Robbins. And there’s a lot of confidence about what you or I would have done if we’d been on the stand. It’s interesting.

MS: We deal with it in the movie, but it doesn’t overwhelm the movie.

KJ: The amount of time we spend on it is relatively small, but in a way it colors the mood. It’s part of the melancholy. Along with the sense of the immense distance between the artist and their art.

MS: That’s a subject I’d looked at in No Direction Home. That equation between Dylan and his music was terrifying to him, when people called him a prophet and told him that he’d changed their lives and that kind of thing. You hear that, and it’s a wonderful compliment, and then it’s: “Okay – now what?” Can you have a simple conversation after that? Probably not. And ultimately, it wasn’t him, it was the songs. Of course, he’d written the songs, they were his, but then, in a way, they really weren’t anymore – they had a life of their own. Which is painful, and beautiful at the same time. Because ultimately, that’s what you want, for the painting or the movie or the novel to take on its own existence. That’s where the old adage to trust the tale and not the teller comes from.

KJ: We settled on a certain way of looking at the question of style. It’s encapsulated in the moment where we’re looking at Dean and Harris hidden by the tree and Davalos coming to confront them, and you say that at the time, you didn’t know anything about technique, you just responded to what was genuine and what wasn’t.

MS: That’s the key. You don’t get interested in films because of camera angles or editing choices. You get involved in them. You’re drawn into the world of the film and the emotional lives of the characters and the conflicts between them. You get older and more sophisticated, and you begin to understand the differences between the pictures that work and the ones that don’t, you start to understand the way films are assembled from so many elements, what direction and editing and lighting and sound design are, how they all fit together, and you develop a growing awareness that every movie is a series of choices. But then, when you make films, you come back to the understanding of what those choices are for. If you’re making narrative films, you’re dealing with emotions, conflicts, trying to build a world in which the characters come to life and the audience connects with them.

KJ: I remember you once telling me that you’ve been drawn, more and more, to simplicity, in your own work and in the movies of others.

MS: Sure, but that’s what you’re always striving for when it comes right down to it. The term “director” is kind of odd and even wrong in a way, but in one sense it’s on target: you’re directing the audience’s eye, their attention, from one moment to the next, through all kinds of means. And yes, when you look at something like the taxicab scene in On the Waterfront between Brando and Rod Steiger, you have the kind of absolute simplicity you’re aspiring to. Kazan, in his autobiography, says that he didn’t really “direct” the scene, he just allowed it to happen. He made some choices with Boris Kaufman, he let Brando and Steiger, who already knew their characters so intimately, interact, and it came alive. Sometimes, that’s what direction is – letting things happen, not interfering.

KJ: It’s a powerful experience to look at that scene with fresh eyes, after it’s been anthologized and clipped in so many award shows and montages. When I talked to Lois Smith about Kazan, she told me that one of the things she valued most about the Actors’ Studio was learning to “account for what happened right now,” being responsive to the moment. The look on Brando’s face when Steiger tries to put the blame on his manager seems to me to be a perfect example of that – staying in the moment within your character, and surprising yourself.

MS: That’s right, and only an artist as powerful and sensitive and concentrated as Kazan could create the conditions where that happens.

KJ: We mention Cassavetes briefly in the movie, and there is a real link there. Cassavetes admired Kazan greatly.

MS: Sure. They’re so different, but you can understand how one makes the other possible. And then John had an enormous effect on me, personally and professionally. And Kazan had a great effect on Francis Coppola, and so many others.

KJ: I’d forgotten that Coppola wanted to cast Kazan as the Jewish gangster in Godfather II, the part that Lee Strasberg played so beautifully. His work had a great effect on so many people.

MS: Right. I hope we did justice to that with A Letter to Elia.

About the Filmmakers:

MARTIN SCORSESE

Martin Scorsese is one of the most prominent and influential filmmakers of our times. He directed the critically acclaimed, award winning films Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, Goodfellas, Gangs of New York, The Aviator, and The Departed. In 2005, No Direction Home: Bob Dylan was broadcast as part of the “American Masters” series on PBS and released on DVD worldwide. Scorsese’s most recent film, Shutter Island, was released earlier this year. Scorsese is currently at work on documentaries featuring George Harrison and Fran Lebowitz. He is serving as Executive Producer on HBO’s series Boardwalk Empire for which he has also directed the pilot episode. He is currently in production on his latest feature film, The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

KENT JONES

Kent Jones is an internationally recognized critic and filmmaker. His writing has been published in magazines, newspapers, websites and anthologies throughout the world, and he is the author of several books. He and Martin Scorsese have collaborated on several documentaries. Jones is now the Executive Director of The World Cinema Foundation. He lives in Manhattan.