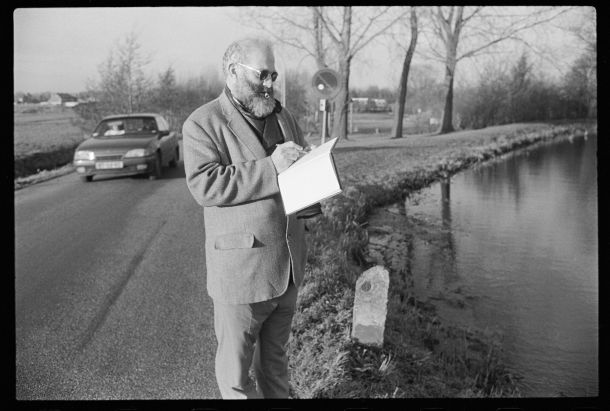

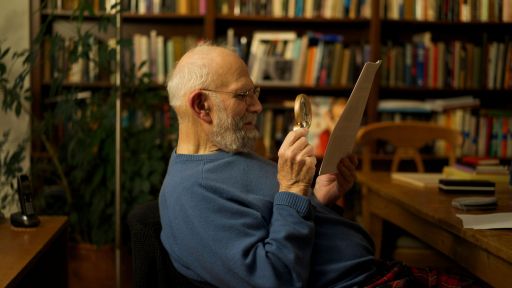

Excerpt from “A Bolt from the Blue,” from MUSICOPHILIA by Oliver Sacks

Courtesy of the Oliver Sacks Foundation

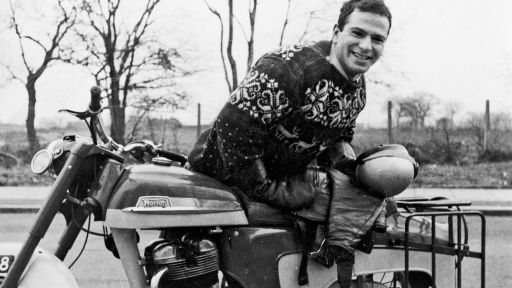

Tony Cicoria was forty-two, very fit and robust, a former college football player who had become a well-regarded orthopedic surgeon in a small city in upstate New York. He was at a lakeside pavilion for a family gathering. It was a fall afternoon, pleasant and breezy, but he noticed a few storm clouds in the distance; it looked like rain.

He walked by a pay phone outside the pavilion to make a quick call to his mother (this was in 1994, before the age of cell phones). He still remembers every single second of what happened next: “I was talking to my mother on the phone. There was a little bit of rain, thunder in the distance. My mother hung up. The phone was a foot away from where I was standing when I got struck. I remember a flash of light coming out of the phone. It hit me in the face. Next thing I remember, I was flying backwards.”

Then — he seemed to hesitate before telling me this — “I was flying forwards. Bewildered. I looked around. I saw my own body on the ground. I said to myself, ‘Oh shit, I’m dead.’ I saw people converging on the body. I saw a woman — she had been standing waiting to use the phone right behind me —position herself over my body, give it CPR. . . . I floated up the stairs — my consciousness came with me; I saw my kids, had the realization that they would be okay. Then I was surrounded by a bluish-white light . . . an enormous feeling of well-being and peace. The highest and lowest points of my life raced by me. No emotion associated with these . . . pure thought, pure ecstasy. I had the perception of accelerating, being drawn up . . . there was speed and direction. Then, as I was saying to myself, ‘This is the most glorious feeling I have ever had’ — SLAM! I was back.”

Dr. Cicoria knew he was back in his own body because he had pain — pain from the burns on his face and his left foot, where the electrical charge had entered and exited his body — and, he realized, “only bodies have pain.” He wanted to go back, he thought, he wanted to tell the woman to stop giving him CPR, to let him go; but it was too late — he was firmly back among the living. After a minute or two, when he could speak, he said, “It’s okay — I’m a doctor!” The woman (she turned out to be an intensive-care-unit nurse) replied, “A few minutes ago, you weren’t.”

The police came and wanted to call an ambulance, but Cicoria refused, delirious. They took him home instead (“it seemed to take hours”), where he called his own doctor, a cardiologist. The cardiologist, when he saw him, thought Cicoria must have had a brief cardiac arrest, but could find nothing amiss with examination or EKG. “With these things, you’re alive or dead,” the cardiologist remarked. He did not feel that Dr. Cicoria would suffer any further consequences of this bizarre accident.

…

A couple of weeks later, when his energy returned, Dr. Cicoria went back to work. There were still some lingering memory problems — he occasionally forgot the names of rare diseases or surgical procedures — but all his surgical skills were unimpaired. In another two weeks, his memory problems disappeared, and that, he thought, was the end of the matter.

What then happened still fills Cicoria with amazement, even now, a dozen years later. Life had returned to normal, seemingly, when “suddenly, over two or three days, there was this insatiable desire to listen to piano music.” This was completely out of keeping with anything in his past. He had had a few piano lessons as a boy, he said, “but no real interest.” He did not have a piano in his house. What music he did listen to tended to be rock music.

With this sudden onset of craving for piano music, he began to buy recordings and became especially enamored of a Vladimir Ashkenazy recording of Chopin favorites — the Military Polonaise, the Winter Wind Étude, the Black Key Étude, the A-flat Polonaise, the B-flat Minor Scherzo. “I loved them all,” Tony said. “I had the desire to play them. I ordered all the sheet music. At this point, one of our babysitters asked if she could store her piano in our house — so now, just when I craved one, a piano arrived, a nice little upright. It suited me fine. I could hardly read the music, could barely play, but I started to teach myself.” It had been more than thirty years since the few piano lessons of his boyhood, and his fingers seemed stiff and awkward.

And then, on the heels of this sudden desire for piano music, Cicoria started to hear music in his head. “The first time,” he said, “it was in a dream. I was in a tux, onstage; I was playing something I had written. I woke up, startled, and the music was still in my head. I jumped out of bed, started trying to write down as much of it as I could remember. But I hardly knew how to notate what I heard.” This was not too successful — he had never tried to write or notate music before. But whenever he sat down at the piano to work on the Chopin, his own music “would come and take me over. It had a very powerful presence.”

I was not quite sure what to make of this peremptory music, which would intrude almost irresistibly and overwhelm him. Was he having musical hallucinations? No, Dr. Cicoria said, they were not hallucinations — “inspiration” was a more apt word. The music was there, deep inside him — or somewhere — and all he had to do was let it come to him. “It’s like a frequency, a radio band. If I open myself up, it comes. I want to say, ’It comes from heaven,’ as Mozart said.”

. . .

Last spring, Cicoria took part in a ten-day music retreat for student musicians, gifted amateurs, and young professionals. . . . It was, Cicoria felt, a good time, a good place, to make his debut as a musician.

He prepared two pieces for his concert: his first love, Chopin’s B-flat Minor Scherzo; and his own first composition, which he called Rhapsody, Opus 1. His playing, and his story, electrified everyone at the retreat (many expressed the fantasy that they, too, might be struck by lightning). He played, said Erica, with “great passion, great brio” — and if not with supernatural genius, at least with creditable skill, an astounding feat for someone with virtually no musical background who had taught himself to play at forty-two.

. . .

Looking at him from a neurological vantage point, I felt that his brain must be very different now from what it was before his lightning strike or in the days immediately following this, when neurological tests showed nothing grossly amiss. Changes were presumably occurring in the weeks afterwards, when his brain was reorganizing — preparing, as it were, for musicophilia. Could we now, a dozen years later, define these changes, define the neurological basis of his musicophilia? Many new and far subtler tests of brain function have been developed since Cicoria had his injury in 1994, and he agreed that it would be interesting to investigate this further. But after a moment, he reconsidered, and said that perhaps it was best to let things be. His was a lucky strike, and the music, however it had come, was a blessing, a grace — not to be questioned.