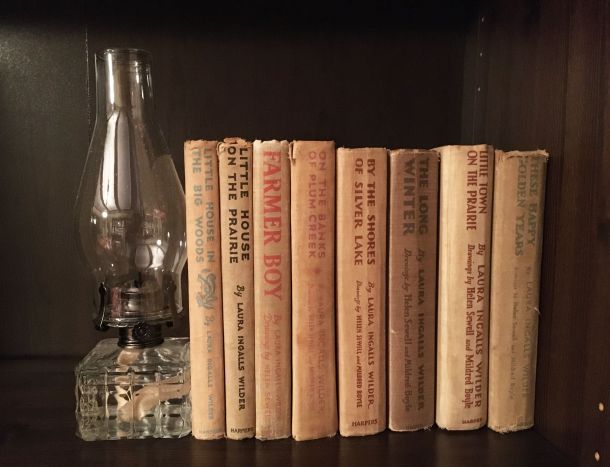

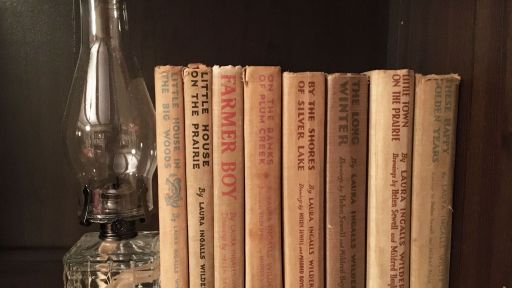

I remember when I first figured out the girl in the “Little House” books was the same person who wrote the books. I was eight and was reading “On the Banks of Plum Creek.” Laura Ingalls, the girl in the book, was about my age. I looked at the cover, at Laura frolicking barefoot in the prairie grass, and then I studied the author’s name on the cover: Laura Ingalls Wilder. The same girl, I realized, but grown up.

I never thought of her as an adult, though. Why would I, when the books practically invited me to play with Laura the girl, to roam the meadows together with our cast-off sunbonnets hanging down our backs? So much of the narrative is infused with Laura’s essential kid-ness — her impulse to roll down haystacks or eat the Christmas candy instead of saving it — that it’s no wonder so many of us feel like we reconnect with our younger selves whenever we curl up with an old paperback from the series.

But while the childhood stuff is always familiar in my re-reading, I’ve found that adulthood looks a lot different in these stories now, different from what I remembered. When I read the books as a child, what they taught me about becoming an adult was pretty grim. For Laura, growing up is marked by stoic milestones: giving up a beloved rag doll she’s supposedly too old for, mourning the death of her faithful brindled bulldog, wearing the corsets that she considers, “a sad affliction.” It means keeping a stiff upper lip and abiding by so many “musts.” It means, possibly, becoming like Ma, with her dull admonishments and “all’s well that ends well” platitudes.

Sure, a few upsides can be glimpsed from time to time — Laura enjoys donning “a young lady’s dress,” and putting her hair up for a party; she feels the satisfaction of earning her own money teaching school. But from what I could tell in my youthful reading, the only truly fun thing about Laura’s coming-of-age was ending up with Almanzo Wilder (I mean, have you seen his photograph? The guy was a sepia tone Adonis.) And even that life event lost its appeal when I got to “The First Four Years,” the novel that serves as a postscript to the “Little House” series, in which all kinds of grown-up misfortunes — debt, illness, child loss, property disaster — befall the couple at every turn. It seemed better to just go back to the beginning, to when Laura was little in the Big Woods.

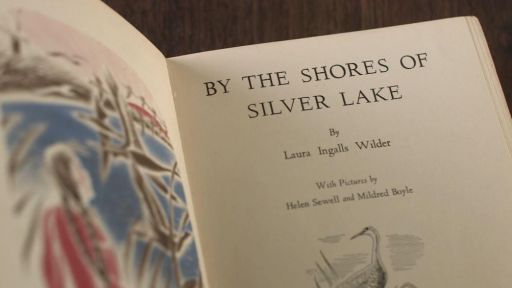

Yet the older I get, the more I’m drawn to those “growing-up” books in the series, starting with “By the Shores of Silver Lake,” where twelve-year-old Laura and her family head west to Dakota Territory. The distance between that fifth “Little House” book and the previous one, “On the Banks of Plum Creek,” feels vast. From the first pages of “Silver Lake,” it’s clear a threshold has been crossed — Mary’s blind; the family has bills; even the land around them is “old and worn out.” Familiar things from the earlier books are gone, like Mary’s golden locks, or else strangely altered: pretty young Aunt Docia from the Big Woods is now the jaded wife of a shady contractor; rough railroad workers belt out a crude parody of the cherished hymn Ma sings in “Little House on the Prairie.” And, of course, Laura loses the reassuring presence of Jack the bulldog (oh, Jack!) and understands she’s “not a little girl anymore.” Grow up, Wilder seems to insist in “Silver Lake,” whether you like it or not.

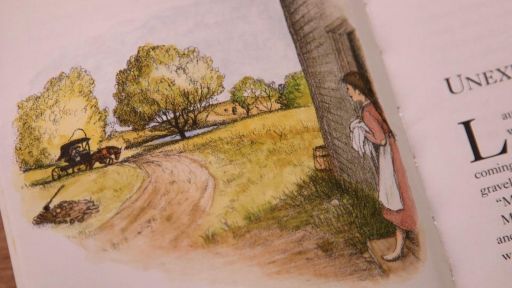

These beginning chapters came as a shock when I first read them as a kid, but now they feel exhilarating, eye-opening. Indeed, the narrative is more open-eyed, more perceptive and self-aware. In previous books, the younger Laura Ingalls always faithfully observes the world around her; in “Silver Lake” she considers, for the first time, the very act of seeing, as she reports the sights on their westward journey to her blind sister. This older Laura understands the difference between the way things appear and the way they are: the telegraph lines outside the window of the moving train aren’t really swooping, but describing them that way is the best way to for her to convey what it’s like to be in motion, traveling at an impossible speed, faster than she’s ever gone before.

Pa made Laura promise to “be the eyes” for Mary, and I used to think of that as just another coming-of-age responsibility for her to bear. But her new-found skills of perception are a gift of maturity, not an obligation. The older we get, the more we understand the power to shape narratives, to choose how we tell our own stories, and to sense the untold stories as well. Consider Ma, that stalwart and uncomplaining vision of adulthood: as the series goes on, a maturing Laura — and we, the older readers — can see things about Ma that Ma herself will never confess: she hates sewing, harbors her own resentments, and won’t be taken for granted. Growing up, it turns out, isn’t about becoming Ma; it’s about understanding who she is.

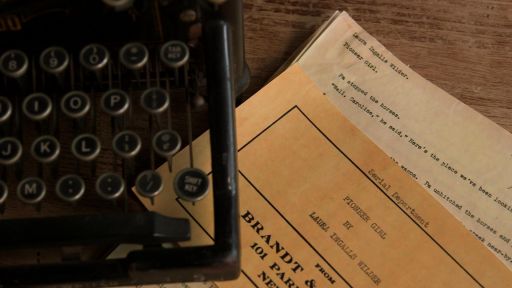

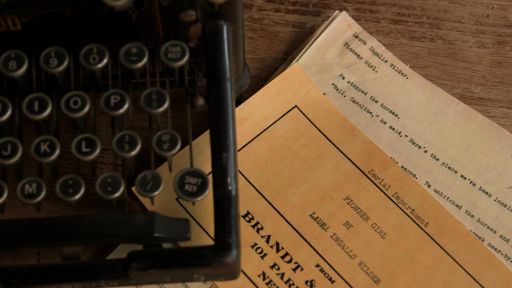

“By the Shores of Silver Lake” could have been a much different novel if Wilder had taken a certain bit of advice offered by her daughter and sometime co-author, Rose Wilder Lane, after the first draft in 1937. According to biographer Pamela Smith Hill, Lane felt that twelve-year-old Laura was too old to be the main character of a children’s novel, and suggested her younger sister, Carrie, replace her. Wilder wouldn’t have it: “We can’t change heroines in the middle of the stream,” she replied in a letter to Lane. With that decision, Wilder made coming of age a key subject of “Silver Lake,” and she continued the theme to the end of the series. She also understood that same audience reading “On the Banks of Plum Creek” in 1937 would be receptive to an older Laura when “Silver Lake” was published in late 1939. In other words, Wilder knew that her readers were growing up.

Perhaps when we re-read the “Little House” books as adults, they stop being children’s books and become something else to us. They invite us to discover what we hadn’t seen before and to reconsider past impressions. Wilder’s willingness to embrace the uneasy journey to adulthood in her novels should inspire us to be clear-eyed about the books themselves, their controversies and modern difficulties, and to welcome discussion and even criticism alongside our fierce original love. Maybe Laura Ingalls Wilder’s novels aren’t quite children’s books anymore, but we can keep growing whenever we read them again.

Wendy McClure is a writer, a children’s book editor, and the author of “The Wilder Life: My Adventures in the Lost World of Little House on the Prairie.” She lives in Chicago.