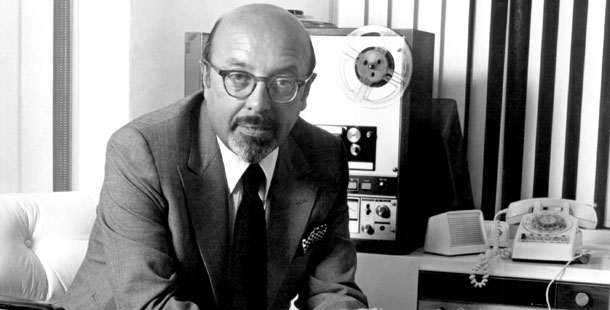

Ahmet Ertegun (1923-2006)

The Greatest Record Man Of All Time

by Robert Greenfield

“I think it’s better to burn out than to fade away… it’s better to live out your days being very, very active — even if it destroys you — than to quietly… disappear…. At my age, why do you think I’m still here struggling with all the problems of this company — because I don’t want to fade away.”

—Ahmet Ertegun

More than most in the $5 billion-a-year global industry he helped build from scratch, Ahmet Ertegun loved the rhythm and the blues. He loved the rock and the roll, jump and swing, and all forms of jazz. More than anything, he loved the high life and the low. When he died at the age of eighty-three on December 14th, about six weeks after injuring himself in a backstage fall at a Rolling Stones concert at the Beacon Theater in Manhattan, the world lost not only the greatest “record man” who ever lived but also a unique individual whose personal and professional life comprised the history of popular music in America over the past seventy years. On every level, the story of that life is just as rich, varied and exotic as the music that Ahmet brought the world through Atlantic Records, the company he founded in 1947 and was still running at the time of his death.

Born in Istanbul on july 31st, 1923, Ahmet Ertegun might never have come to America, which he later called “the land of cowboys, Indians, Chicago gangsters, beautiful brown-skinned women and jazz,” if the Ottoman Empire had not suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Allies during World War I. Occupied by foreign forces, the empire began crumbling in the face of an all-out rebellion led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, a former army major general who would become the father of modern Turkey.

In 1920, Ahmet’s father, Mehmet Munir (he added the surname Ertegun in 1936), a graduate of Istanbul University whose father was a civil servant and whose mother was the daughter of a Sufi sheik, was sent by the sultan to persuade Ataturk to lay down his arms. Switching sides, Mehmet decided instead to become Ataturk’s legal adviser. Two years later, Mehmet was sent to the international conference at which the Treaty of Lausanne was signed on July 24th, 1923, setting the borders of modern Turkey and extending diplomatic recognition to the new republic.

In 1925, Mehmet was named minister to Switzerland and moved with his wife, Hayrunisa; his two sons, Nesuhi and Ahmet; and his daughter, Selma, to Bern. In rapid succession, Mehmet served as ambassador to France (where Ahmet first learned to speak French, the traditional language of the court in Turkey) and then to the Court of St. James (where Ahmet was taught English, which he spoke with a French accent, by a governess who had worked at Buckingham Palace).

In 1932, when Ahmet was nine, his older brother took him to see Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington at the London Palladium. “I had never really seen black people,” Ahmet recalled, “and I had never heard anything as glorious as those beautiful musicians wearing white tails, playing these incredibly gleaming horns.” Two years later, Ahmet was delighted to learn his father had been posted to Washington to serve as Turkey’s first ambassador to the United States during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.

Expecting to be thrust into an America he had only experienced through music, Ahmet was sent instead to the Landon School, an all-boys institution run like a British public school. He then attended St. Albans, whose graduates include Al Gore and George H.W. Bush’s father, Prescott. However, as Ahmet would later note, “I got my real education at the Howard.” Located in the heart of the black district, the Howard was the nation’s first theater built for black audiences and entertainers. At the Howard, the greatest stars of the day – Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton – performed. “As I grew up,” Ahmet would later say, “I began to discover a little bit about the situation of black people in America and experienced an immediate empathy with the victims of such senseless discrimination. Because although the Turks were never slaves, they were regarded as enemies within Europe because of their Muslim beliefs.”

Even as a boy, Ahmet wanted to make records. When he was fourteen, his mother bought him a toy record-cutting machine. Taking an instrumental version of Cootie Williams doing “West End Blues,” Ahmet put it on a Magnavox record player, sang lyrics he had written into a microphone and then amazed his friends by playing the acetate without telling them he was singing. In 1940, the year he enrolled in St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, Ahmet and his brother put on Washington’s first integrated concert at the only venue that would allow black and white musicians to play on the same stage before a mixed audience: the Jewish Community Center.

On Sunday afternoons, the brothers turned the Turkish Embassy into an open house where visiting jazz musicians would jam together in a huge parlor. According to Ahmet, his father soon began receiving letters from outraged Southern senators, saying, “It has been brought to my attention, sir, that a person of color was seen entering your house by the front door. I have to inform you that in our country, this is not a practice to be encouraged.” Mehmet responded by writing, “In my home, friends enter by the front door – however, we can arrange for you to enter from the back.”

When Mehmet died in 1944, at the age of sixty-one, the family left the embassy. Ahmet and Nesuhi were forced to sell their collection of more than 20,000 records, which they had amassed by going door-to-door in the ghetto and hanging out in black record shops. Rather than return to Turkey to enter the diplomatic corps, the brothers decided to stay in America. Moving into an apartment near the embassy, Ahmet began doing post-graduate work in medieval philosophy at Georgetown University, but he spent most of his time at “Waxie Maxie” Silverman’s Quality Music Shop, where he learned the retail end of the record business firsthand.

In 1946, Ahmet and his friends Herb and Miriam Abramson talked Waxie Maxie into putting up the money to start two labels: the gospel-based Jubilee, and Quality, which focused on jazz. After their first few records went nowhere, Waxie Maxie decided he wanted out. Somehow, Ahmet persuaded Dr. Vahdi Sabit, a Turkish dentist who had been a longtime family friend, to mortgage his home and loan Ahmet $10,000 to start his own label in New York. In 1947, Atlantic Records was born.

The rise of independent record companies like Chess, King, Vee-Jay, Modern, Kent, Savoy and Roulette in America after World War II came about because of several factors. The wartime rationing of shellac, a key ingredient in the manufacture of records, had forced the major labels to drop most of their “race music” and country & western artists to concentrate on the mainstream audience. The postwar boom in the economy put money into the hands of working people, many of them black. And then there was payola, a practice that enabled even the smallest label to get its records played on the radio – if it was willing to pay for it.

Atlantic set up shop in a tiny suite on the ground floor of the broken-down Jefferson Hotel on 56th Street in Manhattan. From the start, Ahmet had a vision of what he wanted to put out on Atlantic. “Here’s the sort of record we need to make,” he once said. “There’s a black man living in the outskirts of Opelousas, Louisiana. He works hard for his money; he has to be tight with a dollar. One morning he hears a song on the radio. It’s urgent, bluesy, authentic and irresistible. He can’t live without this record. He drops everything, jumps in his pickup and drives twenty-five miles to the first record store he finds. If we can make that kind of music, we can make it in the business.”

The reason for the demand was simple. America was still a racially divided nation. In even so sophisticated a city as New York, as Ahmet would later recall, “Harlem folks couldn’t go downtown to the Broadway theaters. They weren’t even welcome on 52nd Street, where the big performers were black. Black people had to find entertainment in their homes – the record was it.”

Ahmet’s first major signing was the singer Ruth Brown, whom he had seen perform at the Crystal Caverns club in Washington. On her way to New York to perform at the Apollo Theater in October 1948, Brown was in a car accident and broke both her legs. On January 12th, 1949, Ahmet brought her a contract to sign while she lay in bed. He then handed her a book on how to sight-read and a large tablet on which she could scribble lyrics while she recovered. Atlantic paid the portion of her hospital bill not covered by insurance.

When Ahmet had first seen Brown perform, her biggest number was “A-You’re Adorable,” a Perry Como song that was completely mainstream. As he did with so many black artists who had lost touch with their own musical roots, Ahmet pushed Brown toward a funkier and more down-home sound. In October 1950, she had a Number One R&B hit with “Teardrops From My Eyes.” In 1953, she recorded “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean” with Ray Charles directing her backing band. The song, which Ahmet had her do at four different speeds until he found the one he liked, stayed at Number One on the R&B charts for five weeks and helped put the label on solid ground. By then, many people were calling Atlantic “The House That Ruth Built.”

Because music publishers were not eager, as Ahmet said, to provide material to “a hole-in-the-wall company called Atlantic,” he began writing songs himself. In a recording booth located in a Times Square arcade, he would make a vinyl demo of a song that he would then play for the artist in the studio. Using the pseudonym “Nugetre,” his last name spelled backward, so he would not embarrass his family, Ahmet wrote “Don’t You Know I Love You” and “Fool, Fool, Fool,” which were hits for the Clovers in 1951.

One Friday during the noon show at the Apollo Theater, Ahmet saw Big Joe Turner, who was already thought to be past his prime and had recently been dropped from Columbia, struggling as the vocalist with the Count Basie Orchestra. After the show, Ahmet looked everywhere for Turner only to find him drowning his sorrows in a nearby bar. Telling Turner he was the greatest blues singer ever, Ahmet said that all he needed was new material and persuaded him to sign with Atlantic. He then wrote “Chains of Love” for Turner, which went to Number Two on the R&B charts.

In 1952, Ahmet signed the artist who would come to define Atlantic: Ray Charles. Up to that point, Charles had been playing in the smooth style of Nat King Cole and Charles Brown, and had recorded a minor hit called “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand” for Swingtime. Wanting to push Charles toward a grittier sound, Ahmet wrote two songs for him, “Heartbreaker” and “Mess Around.” Although the session is portrayed in a different manner in Taylor Hackford’s 2004 film biography, Ray, Charles had never before played boogie-woogie piano. As Ahmet began explaining the sound he wanted, Charles suddenly began, in Ahmet’s words, “to play the most incredible example of that style of piano playing I’ve ever heard. It was like witnessing Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious in action – as if this great artist had somehow plugged in and become a channel for a whole culture that just came pouring through him.”

When the Army called Herb Abramson up in 1953 to serve in Germany during the Korean War, Ahmet brought in the Billboard writer who six years earlier had coined the term “rhythm & blues.” Jerry Wexler, an intense, brilliant former street kid from Manhattan’s Washington Heights section, became a partner in Atlantic Records for $2,063.25. Ahmet took Wexler’s money and bought him a green Cadillac El Dorado, the only kind of car in which a self-respecting record man could then be seen. Ahmet, who had always been cooler than cool, was now working alongside someone who generated heat like a steel-mill blast furnace. The two made an incredible pair.

The ultimate story of their time together, which both men loved to tell, concerned the night in New Orleans when they went to find an unknown genius named Professor Longhair who was playing in a joint across the river, where no taxi driver would take them. Their cabbie dropped them off in the middle of a field. After walking a mile in darkness, they saw a brightly lit house in the middle of town so full of people that they seemed to be falling out of the windows as music blared. Talking their way past the guy at the door, who assumed they were cops, the pair made their way inside. Out came Professor Longhair, who played a piano with an attached drumhead that he would hit with his right foot. As people danced, Ahmet and Jerry could barely contain themselves. An utterly primitive, completely original artist was making a kind of music they had never heard before. Rushing up to Longhair after his set was over, they told him just how much they wanted to sign him to Atlantic. “I’m terribly sorry,” said Longhair. “I signed with Mercury last week.” In Ahmet’s version of the story, the pianist then added, “But I signed with them as Roeland Byrd. With you, I can be Professor Longhair.”

By the time Herb Abramson returned from the Army in 1955, Jerry Wexler had physically and psychically taken over his role at the company. Rather than break up their studio partnership, Ahmet put Abramson in charge of a subsidiary label, Atco, and gave him the Coasters and a young piano player named Bobby Darin to work with. By then, Atlantic had moved to a brownstone at 234 West 56th Street. Pushing back the desks at night, Ahmet and Jerry would record in a room with a creaking floor, a sloping ceiling with a skylight in the middle and a young genius named Tom Dowd, who was studying nuclear physics, behind the board. Using the third eight-track recording machine ever made, for which he invented faders to replace the knobs, Dowd recorded “Save the Last Dance for Me” by the Drifters.

During this period, those in charge of Atlantic began to realize that their target audience was no longer rural and black. Rather, it was teenage and white. The message had come through loud and clear for the first time in 1954, when Big Joe Turner’s version of Jesse Stone’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll” was covered initially by Bill Haley & His Comets and then Elvis Presley. In a 1954 essay in Cashbox magazine, Ahmet and Wexler wrote that the blues would have to change to meet the tastes of the bobby-soxers who were looking to find their own sound. What Jerry Wexler chose to call “cat music” would be “up-to-date blues with a beat and infectious catch phrases and danceable rhythms…. It has to have a message for the sharp youngsters who dig it.” To put it another way, the blues had a baby, and they called it rock & roll.

In 1955, Nesuhi, who had married and moved to Los Angeles after his studies for a Ph.D. in philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris were interrupted by World War II, announced he was going to work for Imperial Records, the label on which Fats Domino recorded. Ahmet could not bear the thought of his brother laboring for a competitor and persuaded him to come back to New York to head Atlantic’s jazz division. Within a year, Nesuhi had signed and recorded the Modern Jazz Quartet and jazz bassist Charles Mingus.

Nesuhi also brought Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who had written and produced “Smokey Joe’s Cafe” and “Riot in Cell Block #9” for the Robins on Spark Records. Although the practice was then unheard of in the industry, Ahmet signed them to work as independent producers. In 1957, after two of the Robins left Spark to form the Coasters on Atlantic, Leiber and Stoller’s “Searchin’ ” and “Young Blood” became a huge two-sided hit for the label.

Having failed to produce a hit with Bobby Darin, and feeling as though his time at Atlantic had come to an end, Herb Abramson left the company in 1958. Cash-poor, Ahmet and Wexler managed to raise enough money to buy out Vahdi Sabit. In return for his $10,000 investment in Atlantic, he received between $2.5 million and $3 million, quit dentistry and moved to the South of France. Ahmet and Jerry also bought out Miriam Abramson, thereby making themselves and Nesuhi the sole owners of Atlantic Records.

When Ahmet learned that Bobby Darin was thinking about leaving the label, he took him into the studio in May 1958 and cut “Splish Splash” and “Queen of the Hop,” both of which became big hits because Ahmet wanted Darin to aim his music squarely at the kids who watched American Bandstand on TV each day. Ahmet’s great success with Darin led him to Los Angeles, where he began looking for lucrative pop acts. Concerning the early years at Atlantic, Wexler would later write, “We weren’t looking for canonization; we lusted for hits. Hits were the cash flow, the lifeblood, the heavenly ichor – the wherewithal of survival.” Nonetheless, he found it hard to adjust to the company’s new direction. “As Ahmet grew older,” Wexler wrote, “he grew less judgmental and more interested in a wide range of commercial forms, especially white rock & roll. I stayed with what I knew and loved.”

With money now flowing into the Atlantic coffers, Ahmet was once again living the kind of life he had first learned to love while growing up, with “chauffeured cars, servants, cooks and per diem” in embassies all over the world. In a striking photograph from that era, Ahmet, resplendent in a dark suit with a white silk tie and matching pocket square, can be seen doing some sort of dance step with a gorgeous fashion model named Rosalie Calvert. Both hold drinks in their hands.

During this period, Ahmet hit upon the idea of hiring a bus, which he equipped with a bar so he and all his friends could drink as they went from club to club together. On the rare occasions when Ahmet found himself alone at the end of an evening, he would say, “Let’s go home,” and the driver would take him to the very stylish El Morocco (known as “Elmer’s” to its regulars) on 54th Street for more drinks and more fun.

After cutting the classic “What’d I Say” in 1959, Ray Charles chose to leave Atlantic without giving Ahmet and Jerry a chance to match the offer that ABC-Paramount had made him. Although Ahmet was personally devastated by the loss of someone he considered a friend, he would later note that the relationship between a label and an artist was like a marriage. At the start, there was always a great deal of excitement. Eventually, the artist found someone richer or the label found someone younger. Although Wexler feared the company might not survive, Ahmet said, “Somehow, I wasn’t that concerned. I always figured that we were going to make another hit…. New artists somehow magically appear.”

In the world in which Ahmet Ertegun now lived, the change in sensibility that marked the beginning of the Sixties can best be understood by the fact that the fabled El Morocco was suddenly dead and the place to see and be seen was the Peppermint Lounge, an impossibly crowded dance club on 54th Street, where Ahmet could often be found doing the twist alongside the duke of Marlborough, Jackie Kennedy and Truman Capote.

One night, some friends brought Ahmet to dinner with a woman named Ioana Maria Banu. Called Mica by all who know her, she was, in Ahmet’s words, “a natural aristocrat.” Born in Romania to a family of wealthy landowners, Mica had been forced to flee the country after the communist takeover in 1947. With her husband, an older man who had worked for the royal household, she moved to Canada, where for eight years they ran a chicken farm. Although Mica was still married when she met Ahmet, and he had only recently separated from his first wife, the attraction between them was immediate and intense. Ahmet pursued Mica as only he could. During the time they were courting, he once hid a five-piece band that played “Puttin’ on the Ritz” in the bathroom of her suite at the Ritz-Carlton in Montreal. The two were married on April 6th, 1961.

In a nation reinvigorated by President John F. Kennedy’s promise of a “New Frontier,” civil rights became the predominant issue. “Soul lyrics, soul music,” Ahmet would later say, “came at about the same time as the civil rights movement, and it’s very possible that one influenced the other.” In partnership with Stax/Volt, Atlantic began releasing music recorded by Tom Dowd and Jerry Wexler in Memphis and Muscle Shoals, Alabama. In 1962, Atlantic released “These Arms of Mine,” the first hit single by Otis Redding, who, as Ahmet would later recall, “used to call me ‘Omelette,’ but not as a nickname – he thought at first that this actually was my name.” During this era, Atlantic had big hits by the Mar-Keys, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, Percy Sledge, and Joe Tex. In 1967, Wexler took Aretha Franklin into a studio in Muscle Shoals to record “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You).” While his partner was turning out the greatest soul music ever recorded, Ahmet continued to pursue white rock acts for the label.

Ahmet had first met Sonny Bono through Phil Spector, who had come and gone at Atlantic without producing any major hits. Bono had actually worked as Ahmet’s assistant on recording sessions for the Righteous Brothers, the progenitors of “blue-eyed soul.” When Charlie Greene and Brian Stone, then managing Sonny and Cher, called to say the pair was not happy at Warner Bros., Ahmet signed them to Atco. In 1965, “I Got You Babe” was, as Ahmet would later recall, “a nationwide hit and an international hit – I mean, like nothing we had ever experienced before.”

Greene and Stone then contacted Wexler about another band they had found in Los Angeles. Wexler, who hated dealing with the new breed of stoned-out, longhaired, hippie musicians whom he called “the rockoids,” turned the project over to Ahmet. The band was Buffalo Springfield, and Ahmet was knocked over by the demo of Neil Young’s “Flying on the Ground Is Wrong.” Sitting down on the floor in Los Angeles with Young, Stephen Stills, Richie Furay, Dewey Martin and Bruce Palmer, Ahmet pitched them on going with a record company that would understand their music. “I think they liked the fact that I sat down on the floor,” Ahmet would later tell Young biographer Jimmy McDonough. “When I like an artist, I treat them like a star, and to me these guys were exceptional stars. I thought they were going to be a revolutionary kind of group. It was fantastic to have three great guitar players who were also three outstanding lead singers.” Or, as Young would tell the audience as he was being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1995, “When Ahmet walked into the room, you got good.”

Much to Ahmet’s dismay, Buffalo Springfield broke up after making only two albums. “I think it was one of the few times I cried,” Ahmet told McDonough, “because I just thought that I had the historic group.”

Ahmet, who had been blessed with supreme self-confidence, never worried about failure. The same could not be said about Wexler, who worried about everything, most especially the future of Atlantic Records. By 1967, Vee-Jay had collapsed, and Chess was failing. Wexler told Ahmet and Nesuhi that he wanted to sell Atlantic Records to the highest bidder. When Nesuhi sided with Wexler, Ahmet had no choice but to comply. Atlantic Records was sold in October 1967 to Warner-Seven Arts for $17.5 million, split among Ahmet, Nesuhi and Wexler.

“I didn’t want to sell the company,” Ahmet would later say. “The company was my idea, it was my brainchild, and we were doing well. I saw no reason to think that disaster was imminent. However, they were so insistent on selling, I really didn’t have an option.” In retrospect, with the value of Atlantic Records today estimated between $2 billion and $4 billion, the deal has come to be viewed as somewhat of a catastrophe. Yet Ahmet himself never blamed Wexler for urging him to do it, saying, “I’m thankful for what I’ve got. I’ve lived very well all my life, even when I had no money, and there’s very little I can’t afford.”

In 1969, Warner-Seven Arts was acquired by Kinney National Service, a conglomerate of parking lots, funeral parlors and rental cars, whose chairman, Steve Ross, knew virtually nothing about music. Ahmet announced that he, Nesuhi and Wexler would leave the company once their contracts expired. Faced with the loss of Atlantic’s entire management team, Ross took Ahmet to dinner at 21 in New York along with Warner CEO Ted Ashley. When Ross promised he would give Ahmet anything he wanted without interfering in the day-to-day operations at Atlantic, Ahmet negotiated a new deal for himself, Nesuhi and Wexler. Ross would later claim this was one of the luckiest days of his life.

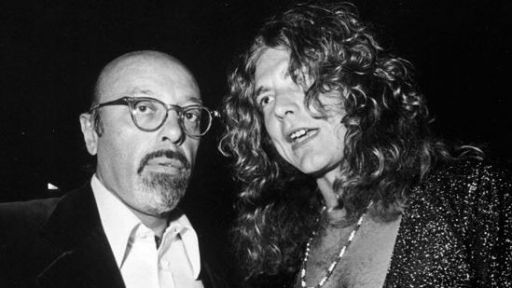

With the era of the small independent label now officially over, rock & roll was big business. Because Ahmet Ertegun was smart enough to understand he would need corporate money to compete in this new industry, he was able to seduce and then sign the world’s greatest rock & roll band.

In 1970, the Rolling Stones’ onerous long-term deal with Decca finally expired. Intent on landing the band, Ahmet flew to Los Angeles to meet with Mick Jagger at the Whisky a Go Go, where Chuck Berry was performing. Before he got there, Ahmet dined with radio programmer Bill Drake, who challenged him to a drinking contest. Both men chugged several bourbons and then enjoyed a dinner that included some expensive wine and more bourbon. Already jet-lagged, Ahmet dragged himself into the Whisky. When Mick arrived, they drank several toasts. As Mick brought up the Stones’ new recording contract, Ahmet’s head sagged forward and he fell asleep at the table. “I couldn’t keep my eyes open,” he told Vanity Fair in 1998. “Mick thought it was very funny.”

While Mick may have been charmed, the deal was far from closed. In London, Ahmet phoned Jagger to say it was time to sit down and make a deal. Mick replied he would be more than happy to do just that after he spoke to Clive Davis at Columbia. Stunned, Ahmet hung up the phone. As he would later recall, “Whenever I saw Mick with someone else, my heart sank. It was a painful, ecstatic courtship.” Picking the phone back up, Ahmet called Jagger and said that while he completely understood his talking to Clive, he could only sign one major act this year and unless he got an answer in a hurry, it was going to be Paul Revere and the Raiders. Then he hung up. For the next forty-five minutes, the phone rang constantly. Ahmet never picked it up. Not long after, the Rolling Stones joined Atlantic.

Landing the Stones confirmed that Atlantic was now the pre-eminent record label in America. Ahmet was so close to Jagger that he had advised him to drop Marianne Faithfull as his girlfriend, warning that her overwhelming drug habit could ruin everything for them both. Shortly after, Mick married the lovely Bianca Perez Morena de Macias in St. Tropez, France. Nor was Ahmet shy about offering musical advice to the Stones. Andy Johns, then twenty years old, was sitting at the board at Olympic Studios in London, having some trouble mixing “Bitch” for Sticky Fingers, when Ahmet sat down in the control room. “Hey, kid!” Ertegun said to Johns, who had no idea who he was. “What you oughta do is add a little bottom to the guitars and turn the bass up.” Johns did as he was told and, as he says, “Bingo! The thing jelled.” After Ertegun left, Johns turned to Keith Richards and said, “Who the f*** was that?” Keith said, “You don’t know who that is? That’s Ahmet Er-te-gun! And he’s been making hit records since before you were born.”

Ahmet trumped everything he had already done for the Stones by throwing them a party on the roof of New York’s St. Regis Hotel to celebrate the end of their triumphant 1972 tour of America. The guest list included Tennessee Williams, Bob Dylan, Huntington Hartford, Oscar and Françoise de la Renta, and a host of titled nobles, with entertainment by Count Basie and Muddy Waters. Culturally, it was a major step in crossing over what had formerly been outlaw music into the mainstream.

On May 3rd, 1975, Jerry Wexler, feeling as though he was no longer involved in decision making at the label, wrote a letter to Ahmet in which he stated, “Under no circumstances, Ahmet, can I be your employee. That’s the bottom line.” Although Ahmet protested, “Man, you can’t quit. It’s unthinkable,” the greatest team in the history of the record business split after twenty-two incredible years. In 1978, Wexler complained to New Yorker writer George W.S. Trow that he never saw his old pal anymore, stating, “Ahmet sees only two kinds of people – social people and morons. And I ain’t either one.” Nonetheless, when Wexler wrote his autobiography, Rhythm and the Blues, in 1993, he dedicated the book to Ahmet Ertegun.

In 1983, after being approached with the idea of doing a television show called “The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame,” Ahmet contacted Rolling Stone founder and editor Jann Wenner, Jerry Wexler, record executives Bob Krasnow and Seymour Stein, and music-business lawyer Allen Grubman with the idea of actually establishing an institution to honor the greatest artists, producers and record executives in the field. Going from city to city, they heard a variety of presentations before deciding on Cleveland as the physical home for the building, which Ahmet insisted be designed by famed architect I.M. Pei. The first Hall of Fame class – which included Jerry Lee Lewis, James Brown and Chuck Berry – was inducted in 1986; the museum opened nine years later. “Ahmet was the guiding moral aesthetic sensibility and consciousness of this thing,” recalls Wenner. “In the end, it was always, ‘What does Ahmet think?’ because Ahmet had the vision. Everyone deferred to Ahmet’s taste, his judgment, his knowledge. I don’t think he consciously thought this through, but he was building an institution to something that he had built. And really memorializing the history of an art form which in great part was his doing.” Ahmet Ertegun himself was inducted into the Hall in 1987. The main exhibition space at the museum bears his name.

In 1988, Atlantic Records celebrated its fortieth anniversary with a gala concert at Madison Square Garden, presenting a marathon twelve-hour show that featured, among many others, a Led Zeppelin reunion, Yes, the Coasters and the Bee Gees. Shortly before the show, Atlantic finally came to terms with Ruth Brown, who had waged a long, protracted and very public campaign on behalf of herself and other artists who had been on the label’s early roster. Atlantic agreed to waive all unrecouped costs charged to their royalty accounts and to pay twenty years of back royalties. Atlantic also agreed to begin limited audits on behalf of twenty-eight additional pioneer artists and contributed nearly $2 million to fund the Rhythm and Blues Foundation, which then pressured other labels to bring about royalty reform and gave money to needy musicians. Of all the companies and record men who had been in business back then, only Ahmet and Atlantic were still around.

At an age when most of the others with whom he’d started in the record business had long since retired, Ahmet was still putting out hits by artists such as Debbie Gibson, Twisted Sister, AC/DC, Rush and Skid Row. When Phil Collins, whom Ahmet considered one of the most impressive artists he’d ever known, played “In the Air Tonight” for him for the first time, Ahmet told Collins that if he wanted it to be a single, he would have to put extra drums on it.

“Labels and artists are never going to get along, because they think we’re brats, and we think they just haven’t smoked enough,” Tori Amos, another artist Ahmet championed when he was already old enough to be her grandfather, told Vanity Fair. “But with Ahmet you know he’s smoked more than you ever did.” She noted that although Ahmet was then seventy-four years old, she could not keep up with him on the dance floor. In 1997, the Atlantic Group, consisting of Atlantic, Rhino and Curb Records, was the number-one label in America, with annual global sales rising to $750 million.

Ahmet began cutting back on his daily corporate duties in 1996. In 1997, he suffered a serious bout of pneumonia. As the result of a shattered pelvis and three separate hip operations, he walked with a cane. Always on the go, he continued to live in unsurpassed style. He and Mica shared a townhouse on 81st Street in Manhattan, an apartment in Paris, a country home in Southampton, New York – with a living room he had demanded be enlarged so that there would be room for an orchestra – and a retreat in Bodrum, Turkey, built with ancient stones from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. His homes were filled with works by Matisse, Magritte, Hockney and Picasso.

In 2001, at the age of seventy-seven, Ahmet produced a session by saxophonist James Carter in Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit, a club so small that a mobile recording studio had to be set up outside. Although it was 110 degrees inside the club, Ahmet, clad in a long wool sport coat, a crisp white shirt without a tie and pressed light tan pants, looked as cool as a cucumber as he ran back and forth from the mobile unit to the stage. Calling the songs, asking players to sit out for a number, telling Aretha Franklin to sing the blues on this one, Ahmet ran the session just as he had done for more than fifty years. The next day, he hosted a lunch for the singer Anita Baker, Kid Rock and Pamela Anderson. That night, Ahmet went right back to the club and did it all over again.

Unlike so many who made it big in the music business only to cash out by selling the companies they had infused with their own lifeblood, Ahmet held fast to the tiller. Until the end of his life, he was still in charge of what he had built from the ground up. That he died after falling backstage at a show by a band whom he truly loved is an ending too perfect for any self-respecting Hollywood screenwriter to have written. A year before he died, Ahmet told an interviewer how he’d like to be remembered: “I did a little bit to raise the dignity and recognition of the greatness of African-American music.”

Although the music business that Ahmet helped create has completely changed, its success still comes down to the quality of a song that people want to hear again so badly that they will happily pay for the privilege. Better than anyone, Ahmet Ertegun understood that need, having experienced it himself from the time he was a child.

And while the fabulous manner in which he chose to live caused all those with whom he came into contact to love him madly, the real reason Ahmet will be remembered is because by dedicating his life to rhythm and blues, rock and roll, jump and swing, and every form of jazz, from Ruth Brown, Big Joe Turner and Ray Charles to the Drifters and Bobby Darin to Buffalo Springfield, Cream, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Phil Collins, Tori Amos, Kid Rock, and Gnarls Barkley, Ahmet Ertegun gave people all over the world, many of whom still do not know his name, the soundtrack of their lives.

—Rolling Stone issue 1018, January 25, 2007M

Editor’s Note: This article has been slightly edited to remove explicit language. The content has not been modified in any other way.