Artist statement from Alejandro Jimenez

On the afternoon of September 24th, during the Q&A portion of a poetry reading, with 100+ high school students in Northern Colorado, a student raised their hand and asked me, “When did you know you wanted to be a poet?”

The student was sitting cross-legged on a chair in the cafeteria of a brand-new high school building, and I was the first guest speaker to recite poetry within their walls. The student was holding a pen and was ready to take notes on the notepad resting on her right thigh. She waited, eagerly and attentively, for my answer. “I don’t think of myself as a poet…” I felt a wave of shame come over me as those words left my mouth, “…so I am having a hard time thinking about a precise time or moment I knew I wanted to be a poet,” I responded. The student, midway through writing something on her notepad, looked at me, confused.

“You know, I guess growing up brown in this country that wanted me gone,” I continued, “I thought that to be a poet I need to be a dead white guy. I thought poetry existed only in places where people like me were not welcomed. However, I am alive and Brown and I continue to be amazed, and grateful, that I am invited to places where I am wanted.”

I finished my answer explaining that I am learning to be comfortable in calling myself a poet. The student wrote some notes down and looked as confused as I felt about my own answer.

Since then, I have been thinking more intentionally, about why it is that I have trouble thinking of myself as a “poet”. If I am being honest, it is a thought that has crossed my mind at least a few thousand times over the last decade but I don’t allow myself to dwell on it.

We all deal with imposter syndrome. Maybe, I am just ignoring it, the imposter syndrome, so I don’t give it more power. And also, to me, conversations about why we create art can seem elitist. I have never wanted my words spent on that.

I have always preferred creating art, rather than discussing it.

When I lead poetry workshops with students of color, they overwhelmingly express their distaste for poetry because they see it as “art for white people.” I share with them that I also disliked poetry for the same exact reasons they express. I disliked it because of how rigid it seemed. I disliked it because it seemed that only white poets were present. I disliked it because I did not see myself in it. I disliked it because this art form, or at least the way it was presented to me, seemed not to want me.

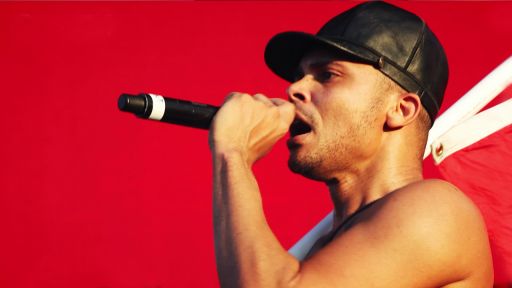

I tell them about spoken-word, and that it has been the type of poetry that made sense to me, and was my access point to this art form.

Before this, I tell them that we have always been surrounded by poetry.

I tell them: corridos are poetry. I tell them that hip-hop is poetry. I tell them that before the written word there was the spoken word. I ask them to think about how their families tell stories. I ask them to describe that setting. I ask them to tell me the smells, the sounds about that setting. I tell them, poetry is storytelling.

It is gossip. It is song. I say that poetry is infinite and there is always a place for them in it.

My number one goal as a poet is to get people who look like me eager to write their stories and dismantle the notion that this art form – poetry – is not for us.

The process of decolonizing is as precise, and intentional, as the process of colonizing. So, while I might have some insecurity about calling myself a poet, the students that I get to work with assure me that I am a poet. The communities I get to visit assure me that I am a poet. Not because I am invited to places where I am not wanted (as I previously believed was necessary), but rather because I am invited to places where I feel complete. And that’s what poetry is for me: following and writing your story to create a home and letting go of any insecurity and/or shame.

Thinking back to that Saturday in the cafeteria, this is what I wanted to say:

I knew I wanted to be a poet when I felt alone, and for whatever crazy reason I decided to share my poetry out loud in public, and people felt a connection.

That was over 15 years ago. I knew I wanted to be a poet when an old Brown lady approached me, crying, after a reading and thanked me for my work – stating that she had waited over 65 years to feel validated and recognized through art. I knew I wanted to be a poet when my grandmother saw one of my performances online and she called me from Mexico and cried while trying to congratulate me. I knew I wanted to be a poet when my mother called me and told me that my father, on his deathbed, asked her to tell me not to let go of the joy that poetry provides me. There are moments in my artistic journey that propel me forward. Sometimes I get to experience those moments often and other times I go months, even years, without feeling purposeful in this art.

But I always come back to this: our stories will always guide us to where we want to be and need to be and will help us build, and strengthen, community. Always. And no one is better at telling our stories than us.

About Alejandro Jimenez

Alejandro Jimenez is a formerly-undocumented immigrant, poet, writer, educator and avid distance runner from Colima, Mexico, living in New Mexico. He is the 2021 Mexican National Poetry Slam Champion, he is a two-time National Poetry Slam Semi-Finalist (US), multiple time TEDx Speaker/Performer, and Emmy-nominated poet, whose work centers around cultural identity, immigrant narratives, masculinity, memory and the intersections of them all. He is a TIN HOUSE Writers Workshop participant. His work has appeared in The Acentos Review, The Latino Book Review, Yellowscene, As/Us Journal, Rethinking Schools and other publications. He has also been featured in Radar2021|Telemundo|NBCUniversal and Tracksmith. His self-published book, “Moreno. Prieto. Brown.” (2017), has sold over 2,000 copies and has been incorporated in curricula across various school districts and universities.

About filmmaker Raúl O. Paz-Pastrana

Raúl O. Paz-Pastrana is a Mexican immigrant filmmaker, cinematographer, and multimedia creator, based in Denver Colorado. His work intersects contemporary art, political documentary, and visual ethnography to explore themes of belonging, alienation, and the concept of “home.” Paz-Pastrana often collaborates with BIPOC artists and academics that are working on bold artistic projects that expose racism and xenophobia, such as the worldwide “Hostile Terrain94” installation and the “Coyotek project” interactive website. His films have screened at museums and festivals worldwide including at the Sheffield Doc/Fest in the U.K., the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI) in New York City, and at the Guadalajara International Film Festival (FICG) in Mexico. His work has received support from the Spark Fund, the Princess Grace Foundation, The Ford Foundation-JustFilms, The LEF Foundation, ITVS, Catapult and the Sundance Institute among others. He is a BAVC MediaMaker Fellow, a Firelight Media Documentary Lab Fellow, a New America National Fellow and a Creative Capital Awards Artist Fellow.

About filmmaker Alan Domínguez

A cultural and national border crosser since birth, Alan Domínguez is a filmmaker who addresses issues such as hate crimes, police corruption, wrongful incarceration and the immigrant experience. Denver based with Nuevo Mexicano roots, Domínguez’s documentaries and narrative films have been screened and distributed in three different continents and in three different languages. His work has been broadcast on Hulu, World Channel, Rocky Mountain PBS, Colorado Public Television, Third World Newsreel and Latino Rebels. Additionally, Alan’s films have been screened at Festival Internacional de Cine en Morelia, New York Latino Film Festival, XicanIndie Film Festival, among others. Domínguez’s films have received support from Imagine2020, Arts in Society, National Association of Latino Independent Producers, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, World Channel. He is a Latino Media Market Fellow, National Association for Latino Independent Producers Fellow, Latino Leadership Institute Fellow and Doing your Doc Fellow.