Early in the twentieth century a new spirit appeared in American life… It was a spirit of change, of dissent–in some minds, the spirit even of revolution. Predominantly it was an upsurge of hopefulness. New directions seemed possible not only in politics and the arts, but also in the quality of life as a whole. Institutions and established ways were subjected to a critical scrutiny that had been rare in the previous generation… Experiment replaced acquiescence to a received tradition as defined by genteel “custodians of culture.”

–Alan Trachtenberg, Critics of Culture: Literature and Society in the Early 20th Century

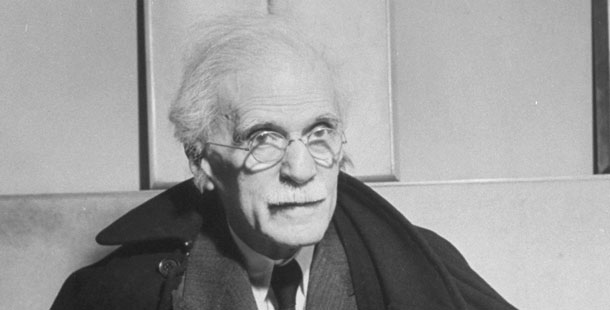

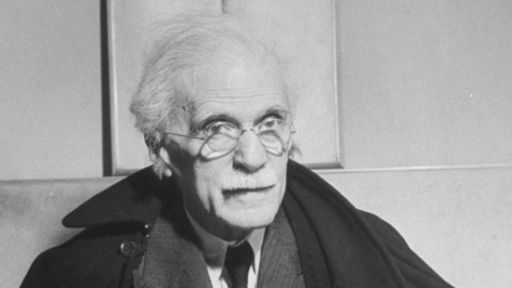

This “new spirit” is perhaps more pertinent to a biography of Alfred Stieglitz than to the life and work of any of his contemporaries working in the arts. The span of Alfred Stieglitz’s life, 1864 to 1946, saw some of the most rapid and radical transformations ever to occur in the landscape of American society and culture. Stieglitz witnessed New York transform from a sleeping giant of cobblestone streets and horse-drawn trolleys to a vibrant symbol of the modern metropolis, with soaring skyscrapers becoming visible emblems of a new age. Alfred Stieglitz’s seminal role as artist and art impresario at a time when American culture was redefining its fundamental ways of seeing, thinking and experiencing the world is the subject of the first full-length film biography of the photographer “Alfred Stieglitz – The Eloquent Eye.” The time is ripe for a major reevaluation of Stieglitz as a photographer, a seminal influence in the arts of the first decades of the century, and as an important interpreter of the emerging modern culture. There is a need to free Stieglitz from the myths–pro and con–that have engulfed him. Stieglitz’s own photographs, and the wide influence of his ideas and activity on photographers, artists, writers and art institutions in the first four decades of the century, define him as a singular shaping force for a new American vision of the arts and culture.

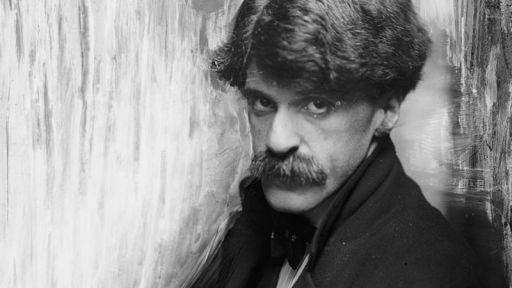

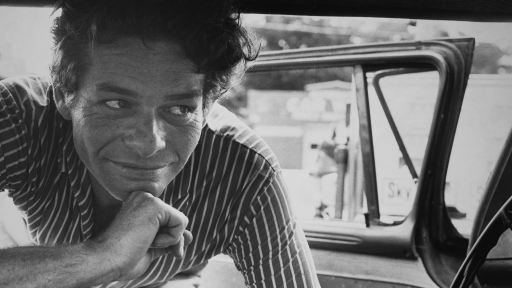

The body of photography that represents Stieglitz’s achievement as an artist was appraised by fellow photographer Edward Steichen as “like none ever made by any other photographer.” The film not only presents some of the most famous Stieglitz pictures, such as “The Terminal”, “The Steerage” and the O’Keeffe portraits, but will give viewers a rare opportunity to see some of the impressive lesser-known photographs, from early images of European peasant life to the late views of New York’s skyscrapers seen from Stieglitz’s window. Stieglitz’s portraits of artists and friends from the ‘291’ period and the subsequent galleries comprise a beautiful and moving record of many of the key figures in Stieglitz’s life and in the art world of the time. By choosing striking and representative images from the different phases of Stieglitz’s career, the film reveals the evolution of Stieglitz as an artist who chronicled the transformation of American society. The strong photographic values regarding subject, composition, tone et. al. formulated early in Stieglitz’s career can be perceived throughout these phases. Some of the great works in the history of modern photography–many made by Stieglitz’s close associates such as Frank Eugene, Clarence H. White and Edward Steichen–will also be shown as the story of modern photography’s history unfolds.

The body of photography that represents Stieglitz’s achievement as an artist was appraised by fellow photographer Edward Steichen as “like none ever made by any other photographer.” The film not only presents some of the most famous Stieglitz pictures, such as “The Terminal”, “The Steerage” and the O’Keeffe portraits, but will give viewers a rare opportunity to see some of the impressive lesser-known photographs, from early images of European peasant life to the late views of New York’s skyscrapers seen from Stieglitz’s window. Stieglitz’s portraits of artists and friends from the ‘291’ period and the subsequent galleries comprise a beautiful and moving record of many of the key figures in Stieglitz’s life and in the art world of the time. By choosing striking and representative images from the different phases of Stieglitz’s career, the film reveals the evolution of Stieglitz as an artist who chronicled the transformation of American society. The strong photographic values regarding subject, composition, tone et. al. formulated early in Stieglitz’s career can be perceived throughout these phases. Some of the great works in the history of modern photography–many made by Stieglitz’s close associates such as Frank Eugene, Clarence H. White and Edward Steichen–will also be shown as the story of modern photography’s history unfolds.

An examination of the evolution of modern photography and of the impact of the medium on the American sensibility opens a window onto many crucial cultural developments of the time. By examining the creative output of the period and the public’s response to it, the photographs become both gauge and index of the public’s and the artists’ responses to the changes going on around them. One can examine the ascendance of the machine, the explosion of urbanization, changes in social attitudes and mores, and the drive for an indigenous modern American culture–all of which often involved a growing tension between the prescriptions of commerce and culture. America also began a new relationship with Europe in which this country was no longer regarded as an isolated anomaly in relation to the rest of Western civilization. As one can see, Stieglitz’s involvement in this dialogue between artist and culture was central enough for cultural historian Bram Dijkstra to write that “it was Stieglitz who… provided the essential example of the means by which the artist could reach out to a new, more accurate mode of representing the world of experience.”