Journalist Kayla Stewart reflects on Alvin Ailey’s lasting impression on American culture.

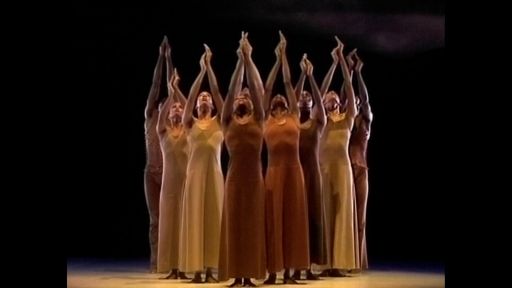

On the stage of the New York City Center, there’s a slight rumbling that emerges from the stage, almost as if it knows the floors will soon be shaken to their core. Black dancers emerge, dressed in garments reminiscent of the Baptist churches that lined the rural south, nightclubs and Biblical stories. The dancers give their full selves to the art, true to the ballet’s creator – Alvin Ailey – a man who no doubt gave his whole self to the ongoing development and expansion of Black American storytelling through dance.

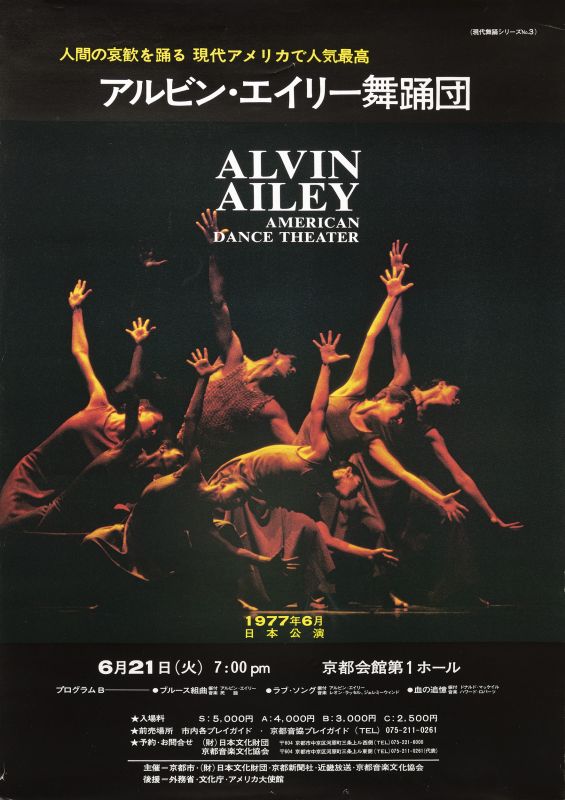

The ethereal movement of dancers captivates audiences – from the concert halls of the Deep South, to theaters around the world. Ailey’s work has mesmerized viewers across generation, border, and time. A dancer, choreographer, and director, Ailey was dedicated to crafting a universal acknowledgement and understanding of Black American life, touching audiences and performers everywhere. When a young Leslie Odom, Jr. saw Alvin Ailey’s work, he was astonished. There were performers – people who looked like him – moving gracefully across the dance floor. Enraptured by the fine, thoughtful movement, Odom saw more than dance – he recognized a story that expressed the nuance and vitality of Black American life.

“He took our everyday and he gave us back beauty,” Odom told the Skimm. “He gave us back fine art.”

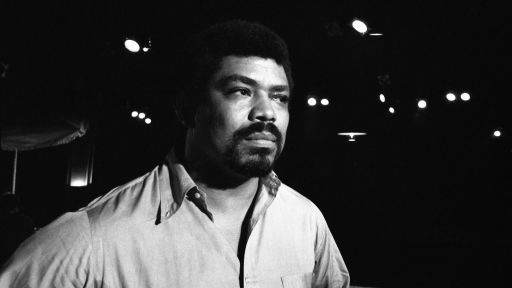

Odom’s reflections express a common sentiment toward Ailey’s work. An expert in capturing the everyday, mundane acts of life and transforming them into high art, Ailey’s contributions to the American ballet landscape and to the global archive of dance allow his legacy to touch generations and people far beyond the concert halls he himself walked during his lifetime. The choreographer used his life, a living demonstration of the challenges and possibilities of Black American life to inform his immense body of work. Born into extreme poverty in Rogers, Texas, Ailey witnessed first hand the brutality of the American South, a visual that would inform the “blood memories” theme he regularly channeled in his choreography. He also, however, witnessed Black exuberance. A young Ailey observed the joy and ebullience demonstrated by Black Americans in the church house, and the nightclubs. Both institutions, albeit constructed for different reasons, provided a space for Black freedom, Black joy and Black movement. These observations would follow Ailey as he moved to California and eventually New York, to pursue a career in dance.

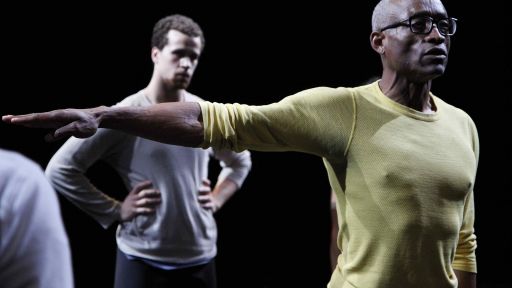

“The most powerful works of art are usually the ones that are the most personal,” artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Robert Battle, recalled Ailey telling him during an interview with The New Yorker.

Ailey’s youth informed much of the work society has come to recognize today. He developed friendships and partnerships with intellectuals, artists, and visionaries. Dr. Maya Angelou, then known as Marguerite Johnson, was one such friend. The two developed an act called “Al and Rita,” one of his earliest public performances. In 1958, Ailey founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which still operates today. The company allowed Ailey to express his perception of Black culture and life. “Revelations,” his signature work, is certainly evidence enough of his genius, but Ailey was responsible for dozens of magnetic ballets and shows. His productions were a reflection of his memory and perception of his surroundings, emblematic of the wide range, yet commonality found within different American experiences. A gay Black man from a small town in Texas, there was perhaps no better person to tackle the oft conflicting lines between navigating identity and humanity in the United States, often right on the dance floor. Ailey’s work was Ailey’s truth.

“The Black pieces we do that come from blues, spirituals and gospels are part of what I am,” Ailey once explained in an interview. “They are as honest and truthful as we can make them. I’m interested in putting something on stage that will have a very wide appeal without being condescending; that will reach an audience and make it part of the dance; that will get everybody into the theater. If it’s art and entertainment—thank God, that’s what I want to be.”

Ailey developed 79 ballets for the public, an astounding offering to the dance world. The choreographer believed that art was a tool to instigate change and believed that through dance, people in and outside of the Black American community could expand their awareness of the diversity of Black American life. Though his work in the United States is certainly valuable, he believed in a common sense of humanity and was eager to address domestic and global challenges in his work. He connected the apartheid of South Africa to the riots of Chicago (1968) in “Masekela Langage“, drawing parallels between both examples of racial hatred. Dance, whether “Revelations,” which documents the line between extreme grief and astounding joy or “Blues Suite,” a delightful meditation on Black American nightlife, were expressions that should be understood by viewers in Senegal, Moscow, France and beyond.

Ailey developed 79 ballets for the public, an astounding offering to the dance world. The choreographer believed that art was a tool to instigate change and believed that through dance, people in and outside of the Black American community could expand their awareness of the diversity of Black American life. Though his work in the United States is certainly valuable, he believed in a common sense of humanity and was eager to address domestic and global challenges in his work. He connected the apartheid of South Africa to the riots of Chicago (1968) in “Masekela Langage“, drawing parallels between both examples of racial hatred. Dance, whether “Revelations,” which documents the line between extreme grief and astounding joy or “Blues Suite,” a delightful meditation on Black American nightlife, were expressions that should be understood by viewers in Senegal, Moscow, France and beyond.

“If you’re a Black anything in this country, people want to put you into a bag,” Ailey once said in an interview. Ailey challenged this boxing of identity and instead crafted an expansive identity that went well beyond choreographer, dancer and Black man. He was, as always, Alvin Ailey. He specifically designed his company to embrace a diverse range of thought and ideology. Especially rare during the early days of the company, Ailey did not require the same dance experience or credentials as some of the other largely white companies. Instead, he hired dancers based on talent and their ability to absorb the meaning of a composition and convey that truth to an audience. Though most of his ballet dancers were intentionally Black American, he strove for an inclusive troupe and would hire dancers from all backgrounds. This method led to some of the most inspired dance displays in American history and is partly responsible for the wide acclaim presented upon the company for decades. Today, the company accepts ballets from all over the world and still employs a diverse set of dancers.

Since passing, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater has presented ballets to discuss the Holocaust (“No Longer Silent“), the Black Lives Matter Movement (“Exodus“) and other socially and politically charged issues and moments in history, such as the ongoing challenge of homelessness in the United States (“Shelter“). The company has also held true to the mission of representing everyday life, showcasing a gay Black couple in “Desire Me” in “Tracks” and “Love Stories.”

Among his many awards, Ailey received the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts, US & Canada, was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP in 1977 and received the Kennedy Center Honors. In 1988, just before his death, he was inducted into the National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame and in 2014 he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. Though Ailey was fiercely private about his personal life, his queerness was integral to his identity and life and in 2019 he became an honoree of the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco’s Castro district, a public demonstration of the world’s appreciation for the fullness of Ailey’s life as a gay, HIV-positive Black man.

Ailey’s life gave the world so much, but perhaps the greatest gift he provided was hope. His work, his art and his thoughtful musings on the complicated world in which society lives constructed one of the most inspired companies in this world. Through his work, he broke down barriers in the dance world, created an expansive display of the diversity of Black American life and created a blueprint for Black dancers and choreographers that would follow. His legacy, evident in the performances that have continued virtually and around the world, show that the dancer’s light didn’t dim when he passed; rather, his work inspired a generation of dancers and thinkers eager to bring hope, joy and empowerment to audiences willing to watch. Ailey isn’t just a choreographer, he’s an American hero and his legacy will live on through every single ballet the audience is blessed enough to see.