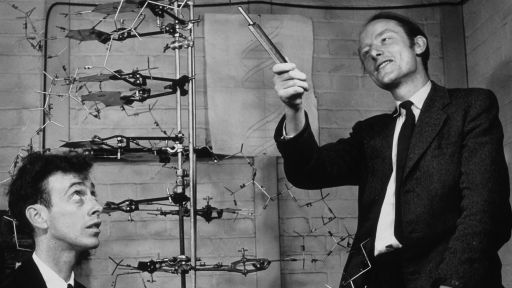

James Watson with a molecular model of DNA, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1957. (Photo by Andreas Feininger/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

by Nathaniel Comfort

“DNA” is a household word. When we read that potent acronym, or see the sinuous twin curves of the double helix, we think “innate,” “fundamental,” “essential,” “science,” “health.” To say something is “in your DNA” is to say that it’s part of your essence, your elemental self. DNA is a meme, a brand, a logo that swivels at the hips like Elvis.

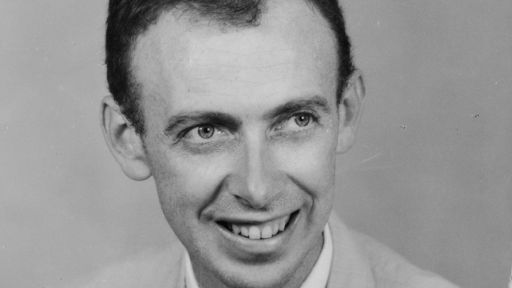

No one has done more than James Watson to make DNA “DNA.” After the double helix, he became DNA’s impresario, its leading promoter and translator, inscribing DNA into both high and popular culture. He gave DNA science its bible — “Molecular Biology of the Gene” (1965) — and the gospel according to Jim — “The Double Helix” (1968).

He rescued from bankruptcy the louche and flyblown Long Island marine station where he had summered with his Ph.D. advisor, his mentor and their merry band of molecular renegades. He transformed it into the modern Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a prestigious institute of science whose lush campus he studded with biomolecular sculpture—simultaneously a gleaming, multinational research university and shrine to DNA.

He led the early Human Genome Project and, when it was deemed complete, he became the first person to have his own genome sequenced, ushering in the age of “personalized” or “precision” medicine.

He became a celebrity scientist, granting interviews, appearing in hip advertisements, going on talk shows. “Think Different,” went the ad for Apple Computer. Think DNA.

Throughout, Watson’s mantra has been that DNA is “the secret of life.” That DNA is not only essential to life but fundamental to it—everything else in biology and society is elaboration.

Did Watson discover the secret of life—or invent it? Suggesting that Watson invented the secret of life takes nothing away from his achievements. But it recasts the DNA story as science’s creation myth—a story, built out of facts, that explains where we come from. With rare, intuitive skill, Watson has spackled those facts together with beliefs and interpretations into a compelling narrative: “the secret of life.” DNA didn’t know it was the secret of life when its cousin, RNA, invented it, billions of years ago. Humans had to give it that meaning. Not alone but like no one else, Watson gave voice to that meaning:

DNA is all and all is DNA.

This is not to deny the value and importance of DNA science. It is to say that the secret of life may have more than one complete explanation.

Like all creation myths, the DNA story has a dark side. As the molecular Moses, Watson spread the word that DNA was the Code and the Code was Good. He became DNA’s leading fundamentalist. He began having racialized visions of a molecular rapture. Many of those closest to him wonder how he could have gone so far astray.

But Watson’s faith in DNA gives him a kind of immortality. The molecule, thread of our existence, will outlive him. It will persist, in nature and culture. DNA abides.

James Watson discovered some secrets of life and spectacularly missed others. But such is the stuff of biography. Our creation myths must be spacious enough to accommodate the messiness of life and those who both live and study it.

—

Nathaniel Comfort is Professor of the History of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, and the author of “The Science of Human Perfection” (Yale, 2012) and “The Tangled Field: Barbara McClintock’s Search for the Patterns of Genetic Control” (Harvard, 2001). He was interviewed in American Masters: Decoding Watson, streaming at pbs.org/americanmasters and PBS apps.