Ric Burns has written, directed and produced award-winning historical documentaries for nearly 20 years. His latest project is a two-part film on pop artist Andy Warhol, a Pittsburgh native who found beauty in everything from soup cans to movie stars. Below, Burns answers some questions about his film.

Q: Eugene O’Neill, the Donner Party, Coney Island, Ansel Adams, New York, and now Andy Warhol for AMERICAN MASTERS. What is it about these seemingly disparate subjects that attracts you as a filmmaker?

A: I think what most filmmakers are looking for in a subject is something which is transfiguring. If you look at the history of New York or the story of Andy Warhol or the story of the Westward migration or the story of Coney Island, the central thing that ties it all together is each one of these events, personalities, institutions, or cities transfigured the reality of American culture completely and continues to do so. The contribution of someone like Warhol in terms of how he changed and continues to change our culture is inestimable.

Q: What interested you in the story of Andy Warhol?

A: The amazing thing about Warhol is that he was so successful at projecting an image of who he was that he actually mesmerized posterity. People have taken him at his word. “If you’re looking for Andy Warhol,” he once famously said, “don’t look any further than the surface of my paintings or the surface of me. There’s nothing behind there.” There’s nothing recherché about the story of Andy Warhol. It’s there in print, in biographies, in letters, in paintings, and movies and friends and memories. If you walk behind the image that he created for himself, you discover one of the greatest stories in the history of art, in the history of American culture, a Horatio Alger story like nothing you’ve ever seen. There is not a person in America who cannot relate with their heart as well as their head to the rags-to-riches story of Andy Warhol, this kid with everything going against him in Pittsburgh – immigrant parents, in the Depression, growing up in two rooms with two older brothers, sleeping in the same bed with them, no indoor toilet, no radio, no hot or cold running water. Not a regular guy, clear to everybody but his mother from the start, small, frail, very bright, very vulnerable, incredibly shy, a host of childhood ailments culminating in St. Vitus dance when he was eight, which basically kind of put the kibosh on his schooling for a while.

He really had every challenge he possibly could have: a gay, dyslexic, poor kid from the wrong side of the tracks who grasped American culture as it came out of the ground in the 20th century more viscerally, more intuitively and more brilliantly than anybody before us and who came to New York, implausibly, in 1949, with $200 in his pocket, and 10 years later bought a townhouse on Lexington Avenue. He transformed himself into the most highly paid and most successful and well thought of commercial artist in America. At which point the story hadn’t begun yet, at which point he still wasn’t Andy Warhol, the Andy Warhol.

Q: Put your film in the context of the culture of that time.

A: We will probably never fully tally what happened in the 1960s. It was a transformative few years which really began in November ’63 when JFK was shot and ended in ’68 or ’69. In the film, we start in Pittsburgh in 1928 and end with Andy’s death. But it’s a film about the 1960s because Andy was about the 1960s. Andy lived the life of his culture. He was the opposite of the cloistered artist who goes into his studio and shuts the door. He couldn’t have made art under those circumstances. He was about opening the door. He was absolutely the supreme multimedia artist of the 1960s. Not a hippie. Who knows what his politics were?

Q: Are there any misconceptions about Andy Warhol that your film addresses?

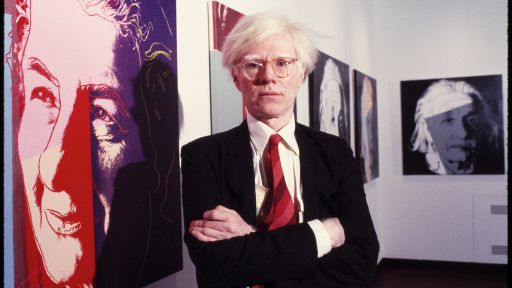

A: That he wasn’t an artist, that it was all a fraud, that it was all about marketing. You can go out and find people today who think that he was a sham and a travesty and that it was all smoke and mirrors. And they think that they have all the arguments marshaled. He didn’t make his stuff. It was all reproduced. Those are people who are not willing to confront his artistic output. It’s so wonderful to work on a project like this because you’re surrounded by great art basically every minute of the day.

Q: Where did a poor kid from Pittsburgh get his imaginative spark?

A: The great cultural critic, Wayne Koestenbaum, who’s interviewed in the film, said, “Imagine that an artist, Andy Warhol, learned his art not from Picasso and Matisse and Rembrandt but from Lana Turner, Shirley Temple and his mother, Julia Warhola.” By the time he was eight, he was obsessed with Shirley Temple, and he understood the narratives of poor little rich girl, which became the title of one of his own films with Edie Sedgwick in 1965. At a time when it was thought that everything commercial, everything representational was by definition debased and non-artistic he said, no, the commercial is just as artistic as the non-commercial. The fallen world of soup cans and Brillo boxes and iconic Hollywood images tells us as much about who we are than action drip paintings, than color field paintings, all by artists whom he admired: Pollock, Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, Bob Rauschenberg. He was tremendously erudite in contemporary art and in the history of art.

Q: Was Andy Warhol a great artist?

A: He was absolutely the greatest artist not only of his generation but of the second half of the 20th century. He may have been the greatest artist of the 20th century. Already it’s the case that if you asked anybody on the street who knows perhaps nothing about art, to think of two painters and name the painting, one painting of each of them, I guarantee you, I could tell you what the answer is already. Leonardo, The Mona Lisa. Andy Warhol, and I’ll name one of two or possibly both paintings: Soupcans and Marilyn. The very greatest artists leave the holy precincts of fine art in terms of their impact. They escape the specific gravity just of the art world, and Warhol was obsessed with doing that. He wanted to make art that was immediately legible and powerful to not just the priestly sect of people who buy, sell, collect and argue professionally about art, but to anybody who could come up and go “Wham! That means something to me.” It was crucial to him.

Q: What did he think about fame and celebrity?

A: He wanted to be successful. He wanted to be rich. He had to be famous. If he was not himself famous, he would have, somebody once said, killed himself. He understood that fame and celebrity were the most important reality in a mass media culture. The glue that holds us all together is a glue whose table of contents is Babe Ruth, Jackie Kennedy, O.J. Simpson. We know who we are, and we know we belong to the same group because of this extraordinarily complicated sort of currency called fame and celebrity, distributed through the mass media. It tells us who we are. It tells us what we want to become. It’s where we find our commonality, and he was going to be the poet laureate of that media culture and the supreme archaeologist of the society devoted to celebrity and obsessed by fame. And the fact that he himself was obsessed by it in no way, it seems to me, either contradicts or invalidates his desire to be the supreme archaeologist for it.

Q: Why do you think he seized the imagination of the general populace?

A: He was like a Jacksonian Democrat. He understood that what art is about is what human beings are about. Art is about transformation. Art is about the desire to be or imagine yourself as something other than who you are. And that it’s something which all human beings participate in. All children play those games. That’s why Shirley Temple was more important to him than Jackson Pollock. It’s all about who you would like to be. Art is about the most basic human desire, which may be as powerful as the need for food and sex – to transubstantiate yourself into something else. And that the iconic images, which became the subjects of his paintings, whether they’re soup cans or Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley or electric chairs, are the images that galvanize us at the most basic level. It was like he had a geiger counter in his imagination that went, “This is hot. This is what someone cares about. This is what they hope for or fear at the deepest level. I will make that the subject of my next painting.”

Q: How has the value of his artwork changed over the years?

A: As time goes on, literally year by year, not only do the prices of his paintings go up, his value on the stock market of critical opinion simply gets higher and higher and higher and higher. The paintings that once scandalized people, people no longer can even understand how to ask the question, “Is that art?” anymore. The Marilyns, the Triple Elvises, the Soupcans, which sold scarcely one in 1962 in their original exhibit in the Ferris Gallery in Los Angeles, they’re probably worth $100 million now, those 32 paintings. He’s created works of art which have penetrated to a very elite realm. They’re invaluable. And why are they invaluable? Nobody we know is going to go out and buy it. It’s at MoMA now, those 32 “Soupcan” paintings.

Q: What about his screen tests?

A: They were three-minute screen tests. But they were not screen tests for anything because there was no movie that was going to be made. They were the movie. There’s Salvador Dali, Bob Dylan, Dennis Hopper. The list goes on and on and on. Baby Jane Holzer. Edie Sedgwick. Gerard Malanga. Everybody in the Factory, every crazy person who walked in the door. They’re overcranked, which means they’re shot at one speed and projected at another speed, which means they’re all slightly slowed down. Slowing them down, so that you’re watching someone blink, so that you can see the blink take place, are ways to make you see the object world, the real world, in a way that you wouldn’t see. And what you’re doing is you’re watching somebody. There’s no cross-cutting. There’s no different camera angle. All the frame flashes and the light leaks, the accidental jerks of the camera are included in there. Why? Because he’s not interested in the fiction that you and an actor and a filmmaker are typically making up in the course of making a movie. He’s interested in two real things: The real thing that’s before the camera and the real thing that’s watching the movie.

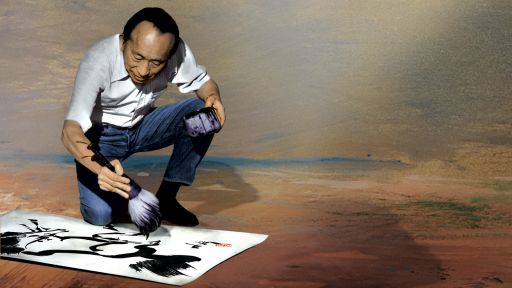

Q: He produced an incredible amount of work in his lifetime. Tell us about that.

A: His great mentor and rival in this respect was Picasso. He was always obsessed with, “How many paintings a year did Picasso do? How am I going to do it?” And he was like a great businessman. “How do we do it? Volume.” He was intent on producing at a prolific rate that’s really frightening and astonishing and not just in painting but across so many different media. Wayne Koestenbaum said in our film, which is so moving to me, “Why do we look at art? We look at art because we want to redeem the garbage in our lives.” And that’s what Koestenbaum sees when he looks at Andy Warhol: the maximum redemption of lost meaning. In an almost spiritual way, Andy was going to redeem it all for us.

Q: Was Warhol religious?

A: His entire life he went to church. There are many Catholics who feel that such a man certainly did not go to Heaven when he died, and there are many ways in which he comported his life which were outside the radius of the catechisms. But he was absolutely religious. Believed very powerfully in God. Try looking at his films, which are going to become much more widely seen. I’m talking about the movies made between 1963 and 1968, which are astonishing. Absolutely astonishing. Kiss, Sleep, Couch, some of them, in some literal sense, pornographic. But even the ones which are pornographic in that they show straightforward sexual coupling, gay or straight, what you very quickly realize is they’re as unpornographic as they could possibly be. The same unvarying intensity of gaze is watching the world in Sleep, a six-hour film about a man sleeping, as is going into any of the ones that are more obviously erotic and it’s the same impulse to look at the world and to see its beauty. And at some level it’s about art and maybe in a funny way it makes it powerfully Christian art. In any case, Andy wanted every moment to last. He wanted to see the beauty because he knew that if things were beautiful, then they last. Things that have beauty have a kind of fame to them.

Q: How did the city of Pittsburgh influence his art?

A: He once said, “We all live a kind of a double life. We all have our real America – Pittsburgh, Texas, Wyoming – and then we have a fantasy America, which is our dream of what everybody else is doing and all the places that we’re not.” And in a way what his art is about is those things that flash between the places we really are and the places we’re dreaming of being, and so I think his art is always about Pittsburgh. It’s always about that kid who sat looking out a window, because there was no radio, for hours at a time. He’s the kid who walked three miles each way with his mom to a church to sit for hours on end watching the absolutely flat screen of the altar. No works of art more resemble Andy Warhol’s paintings of Marilyn or Liz or Jackie than the iconic images in a Byzantine Catholic church, totally representational and absolutely not naturalistic at the same time. When it came to 1962, the day news came out that Marilyn had killed herself, when he decided that day to do a painting of Marilyn, in a sense he was reanimating the Pittsburgh experience that told him that movie stars were our religious icons. I think he meant it in a very literal way. “These are the images that have impact. These are the things that speak to us deeply.” Go look at a Marilyn painting and try to tell me it’s not one of the most moving paintings you’ve seen.

Q: What role did commercialism play?

A: Andy’s the amateur. He’s the guy who’s the commercial artist who’s absolutely condemned and derided for being just a commercial artist, who comes in and takes the world by storm. Why? What did he learn as a window dresser at Bonwit Teller? He learned that as you walk down the street, and your head swivels over towards the window at Bonwit Teller, wham, something grabbed you or didn’t. He had a total respect for those things that grab. What is most artistic is also what’s most commercial. It’s that thing that leaps out and grabs. It’s the hook. It’s the ploy. It’s the McGuffin that makes you turn your head and keep looking for a heartbeat and then pretty soon you’re standing there watching and looking and you’re caught and you buy. He understood that art and commerce and democracy were three sides of a holy triangle and that they were all about out transformation of reality.

Q: What did you learn about him from his brother, John Warhola, who is interviewed in the film?

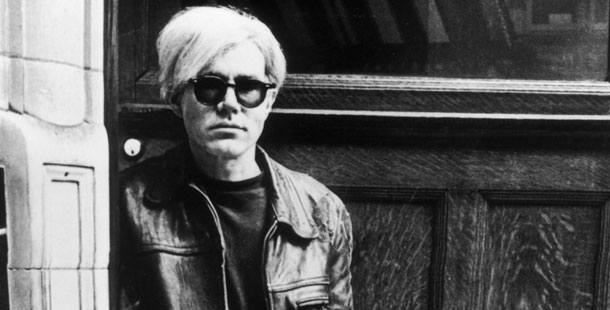

A: That he was vulnerable like a snail without a shell and like people who are vulnerable like that, he had to create a barrier around him. He had to create a prosthetic psychic armor. That’s why you see him with his leather on and his sunglasses sitting in his chair because he really feels it’s all coming in, hurtling in, and he has no protection. So he created a sort of psychic device, which is an armor to take the place of the kind of inner armor most of us have, that we carry around with us, that allows us to feel buffered from the world. Andy didn’t have that. You know, the image of Andy Warhol, seven, eight years old, lying in bed for months on end trying to recuperate from this neurological siege, taking in fanzines, movie magazines, compulsively drawing pictures, both taking in and generating images, as if there was just a kind of free flow in both directions for Andy, no barriers, a free flow of images and feelings. It made him a very complicated person.

Q: Tell us about the attempt on his life.

A: People often were seduced by him, wanted things from him, thought he’d proffered things, held out things which weren’t going to be there. Here was a person who could seem infinitely open – a stranger could walk in the door and in five minutes find themselves in rapt conversation of the kind where time would seem to be abolished. The promise he seemed to hold out to a lot of people was that everybody would be famous for 15 minutes, and when that turned out not to be true for somebody named Valerie Solanas, the psychic impact was so great, she had to kill him. It was like kill or be killed. When he turned his back on her, as he had to, he’s not his brother’s or his sister’s keeper, when that turned out to be the case, that lack of boundaries was literally almost fatal to him. And, hence, this tremendous coherence to his story. It was not an accident that he was shy. It was a non-accident waiting to happen. When you let everything in, sooner or later, everything is going to come in. There were symbolic boundaries and real boundaries that were put up in the wake of the shooting in ’68.

Q: How did things change at the Factory after the shooting?

A: The Factory was like the most porous social creative environment ever created, 24 hours a day, people in and out, anybody, socialites, contessas, drag queens, drug addicts, Walter Cronkite, Judy Garland, you name it. During a five-year period from January ’64 until May ’68, it was the Grand Central Station of our culture. The shooting took place in May, the week before Bobby Kennedy was killed. And the doors were locked at the Factory. Now it was, “Who are you? Why are you here?” You had to show your identity papers, in some sense metaphorically. And that meant that the cast of characters in the Factory changed. In large part the transvestites were driven out. It was quite bad for the drug addicts and it became a straighter place, and he became more business-like, and he didn’t want to die. One of the most moving things I’ve ever read, he said, “I’m afraid of God. And having died … I’m afraid of God. And I’m afraid of death. And having died once, I should be. But I am. I’m afraid of God.” He heard the doctors say, “He’s gone,” on the gurney at St. Vincent’s. He was revived, and he really understood that he was living on borrowed time. Every organ except for his heart and lungs was perforated by the shot. It is a miracle he lived through it. His life changed, and the life of the culture changed. And he knew it.

Q: If he’d lived, what would Andy Warhol be doing today?

A: For the man who said in the early 1960s, “In the future, everyone will be world famous for 15 minutes,” for the man who is the master of all media – way before Howard Stern – he would have understood what the Internet was all about. He anticipated what multimedia was all about. He really was a prophet. He understood where culture is going. He could draw out the lines of ramification and sometimes, in a funny way, he was so far ahead of himself and the world that by the time his own interest was up, the world hadn’t even begun to catch up with him. Looking back from the standpoint of 500 years, he will loom so, so large.