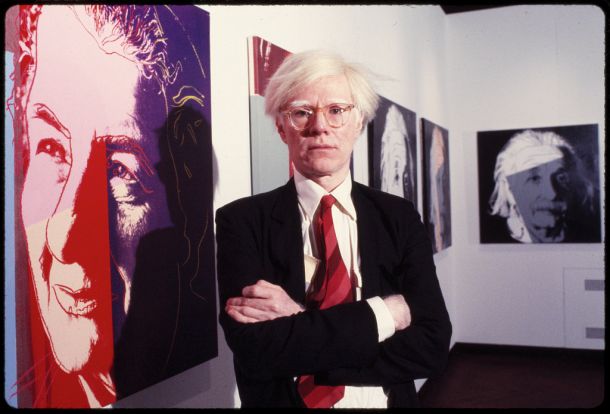

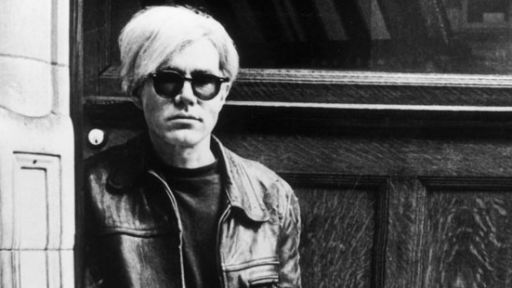

American Masters Multimedia Producer Cristiana Lombardo looks at how a fascination for the thin line between reality and fiction drew Andy Warhol and author Truman Capote together.

In the mid 1960s, Andy Warhol dramatically declared his retirement from painting to pursue other art forms. In his 1980 memoir “POPism: The Warhol Sixties,” he reflected that “art just wasn’t fun for me anymore; it was people who were fascinating and I wanted to spend all my time around them, listening to them, and making movies of them” (142). Just as he had prophesied that “in the future everybody will be world famous for fifteen minutes,” his pursuit of interest in everyday life, people and conversations presaged social media. To record his conversations with “fascinating” people, Warhol chronicled his life with a Sony Walkman, affectionately referred to as his “wife.”

One such fascinating subject was famed author and playwright, Truman Capote. Although the two eventually bonded, Warhol’s fixation with Capote predated their friendship by decades. In fact, Warhol’s first solo exhibition in 1952 was called “Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote,” years before they officially collaborated. In 1956 and 1957, Warhol also depicted collages of shoes further inspired by the author.

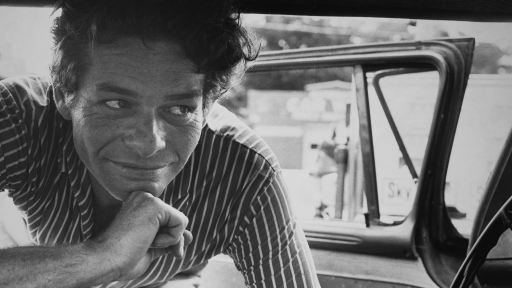

The author, screenwriter and playwright was no stranger to being an artistic muse— he was also childhood friends with Harper Lee, serving as the inspiration for character Dill Harris in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” In a 1973 interview with Rolling Stone, Capote said Warhol pursued a friendship by mailing him letters and drawings. Gary Comenas’ oral history of Warhol quoted Capote as saying:

“When he was a child, Andy Warhol had this obsession about me and used to write me from Pittsburgh . . . When he came to New York, he used to stand outside my house, just stand out there all day waiting for me to come out. He wanted to become a friend of mine, wanted to speak to me, to talk to me. He nearly drove me crazy” (LG187).

Katharine Graham and Truman Capote at a party, 1966. Library of Congress. Credit: World Journal Tribune, Inc.

After the success of “In Cold Blood,” Capote’s celebrity as a successful author was nearly matched by his notoriety as a socialite. In 1966, Capote threw a masquerade party at New York’s Plaza Hotel dubbed the Black and White Ball. The guest list included hundreds of notable attendees, including an unmasked Andy Warhol eyeing Capote. Their paths finally professionally crossed in 1969 when Warhol traded a portrait of Capote in exchange for a year of columns for Warhol’s magazine, Interview. Known as “the crystal ball of pop,” the magazine often published unedited conversations with artists and celebrities.

Eventually, Capote and Warhol struck up a unique kinship—one based in a mutual appreciation for the thin line between fiction and non-fiction. Unlike artists who revel in privacy, Warhol chronicled his experiences with hours of audio recordings, leaving behind roughly 3000 audio tapes—six of which were between him and Capote. The creative collaborators preserved more than 80 hours of documented conversation—some published in Interview and some encounters recalled in “The Andy Warhol Diaries.” The recordings straddled between performative and authentic. One diary entry dated Thursday, June 29th, 1978, noted that Warhol aspired to use their conversations as the basis for a play:

“I told Truman I would tape him and we could write a Play-a-Day, he could act out all the parts himself . . . I think Truman likes me because I like everything he doesn’t. He’s so nuts, you’re embarrassed sitting there with him.”

Although Capote was excited to write a fictional “Play-a-Day,” Warhol recalled clarifying, “can’t I just tape you, the real thing, and do plays about real people?”

“Conversations with Capote,” as they were called in Interview, were advertised as “talk so brilliant it reads like a play, by the one and only [Truman Capote].” Warhol, in his fashion of merchandising art, used Capote as a promotional vehicle for the magazine, running ads and promotions such as Capote-autographed issues in exchange for a two-year subscription.

However, friendship and admiration did not protect Capote from Warhol’s notoriously biting criticism. Writing in his diary on August 28, 1978 upon Capote’s return from rehab for addiction, Warhol said:

“ . . . maybe Truman never did write any of his own stuff . . . Truman showed me a script he did and it was just awful, and when he shows you these things you can’t imagine that he could ever THINK they’re any good, they’re so bad . . . the things Truman SAYS are interesting so somebody else could find clever ways to make them good on paper.”

It seemed their relationship would continue to be hot and cold as Capote struggled with finances and health. Late in 1978, the two affectionately graced the holiday cover of High Times magazine together. By then, they had become staples of New York’s night scene. Among Capote’s literary archive is an oil painting by Warhol of a Studio 54 “VIP” invitation—the storied night club where the two often partied in the 70s. Both Warhol and Capote were regulars at the nightclub. Warhol gifted the painting with the inscription, “To Truman Love Andy ’78.”

Though the two remained friends until Capote’s death in 1984, Warhol struggled to empathize with Capote’s withdrawn demeanor and personal struggles with addiction, making remarks in his diary like: “Truman wasn’t drinking so he was boring again.”

On February 1st, 1980 Warhol recalled:

“He’s like a different person now, he’s very distant, not friendly. . . it’s strange, he’s like one of those people from outer space—the body snatchers—because it’s the same person, but it’s not the same person.”

On Sunday, December 22, 1985, a year following Capote’s death, Warhol wrote about his frustration over never finishing their plays:

“If I’d only looked at it all before he died, I would’ve followed him some more for three days and kept my mouth shut and really gotten something.”

Orbiting one another throughout their careers, it’s clear that Warhol and Capote bonded over a fascination with the intersection of art and reality. Though they never completed a “Play-a-Day,” these two American icons left behind numerous recordings of their interactions — left to us to discern what’s real or imagined.

Works Cited