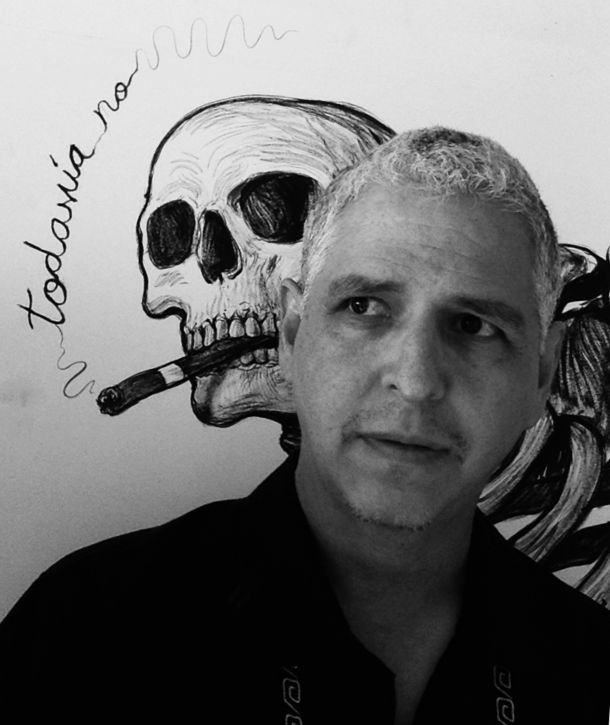

Artist Hugo Crosthwaite fuses portraiture and figurative drawings into dynamic compositions influenced by images from the U.S./Mexico border.

Most known for his stop-motion animation and public murals, Crosthwaite was awarded first prize in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. As part of this distinction, he was commissioned to create a portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci for the National Portrait Gallery.

Months of drawings, photos and observation culminated into Crosthwaite’s piece, not a traditional painting on canvas, but a five minute stop-motion animation covering Fauci’s vast career. In this Q&A, Crosthwaite shares his artistic process, inspiration and interactions with Fauci.

1. Why did you choose to illustrate Fauci in this unique way?

I don’t feel particularly confident as a portraitist, at least when it comes to comparing my work with artists from the past that I admire, like John Singer Sargent or Lucian Freud, so I decided to tackle this important commission in a unique way, by creating a narrative with Dr. Fauci.

Rather than focusing on a traditional portrait that describes his appearance, I wanted to tell a story that is universal and could be understood beyond his likeness. I also felt through our conversations that he is a very modest man. I got the sense that he didn’t want a “grand,” “historical,” traditional looking painting as a portrait.

So I decided to create a stop-motion drawing animation which is an audiovisual medium, showing drawings that include music and sound, illustrating Dr. Fauci’s long career in public service.

2. Why was it important for you to expand the portrait beyond the traditional image of subject? There are colleagues, patients, protestors, etc. within the frame as well.

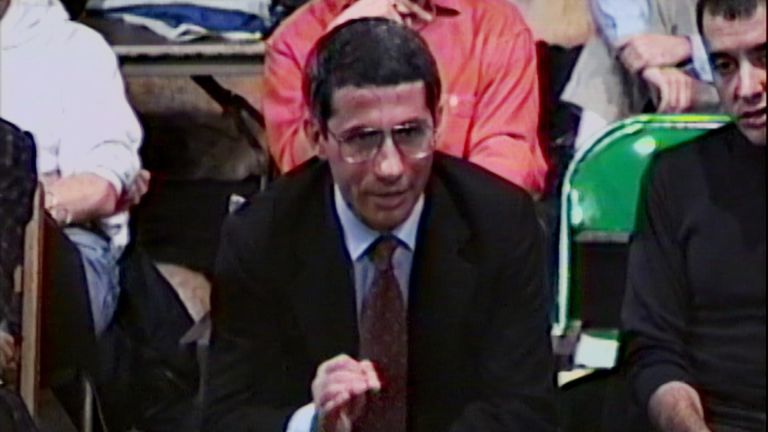

Still from Hugo Crosthwaite’s stop-motion animation portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, on view at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

Making this portrait was an opportunity not just to create a likeness of Dr. Fauci for the National Portrait Gallery, but to capture a particular moment in history that I was living through together with the rest of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic.

So I felt it was important to place Dr. Fauci as part of that living history, with people facing the consequences of rising pathogens, social and political upheavals and the communal attempts to survive disease and pandemics. It depicts the two historical bookends of Fauci’s life: his role in the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and the pandemic of 2020.

The portrait is as much about struggle, suffering and death as it is about Dr. Fauci, so it shows much more than just an individual story about one man.

3. What was it like sharing the piece with Fauci? What was his reaction?

It was incredibly exciting. I felt honored to share this with Tony. Like most of us, I had never heard of Dr. Fauci until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was in awe after learning about his incredible career, his commitment to public service, and I was overjoyed at his reaction to my work. I was relieved after I showed it to him that he didn’t ask for any edits. A huge win for me!

He wrote me a lovely email stating that he loved my drawings and very much appreciated the portrait which portrayed him as taking part of a larger, shared history. He also loved the innovative choice of stop-motion animation drawing.

4. You described Fauci as a “personification of science.” How did that come across in your art?

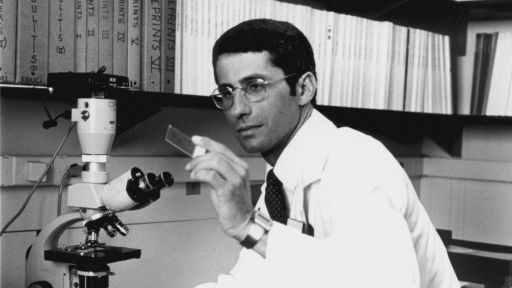

Still from Hugo Crosthwaite’s stop-motion animation portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

Through the narrative of my animation, I wanted to show how perhaps as an accident of history, Dr. Fauci became a divisive figure; to some a “personification of science” at a moment when truth and facts became politicized and rejected by a sector of the population that wants to believe in misinformation and conspiracy theories. It reminded me of Henrik Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People,” where the only person telling the truth and doing his job properly suddenly becomes a pariah.

The overall story in the film illustrates the different roles and meaning that one takes as time passes, but Dr. Fauci’s personal commitment to truth and science remains this constant variable through it all. A doctor not just fighting disease, but anti-reality and anti-common sense.

My film is kind of a public service announcement about the ultimate public servant.

5. How do you view the relationship between science and art?

The majority of science is about observation, what you are seeing, what is there, what you can prove physically. The practice of drawing is an exercise in observation, it is seeing and thinking critically, but art also involves imagination, which is something that propels science. Both are important and serve each other, something that Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michaelangelo took to great heights.