Written by Louis Black, this article was originally published by the Austin Chronicle on October 3, 2003. Read the original piece here.

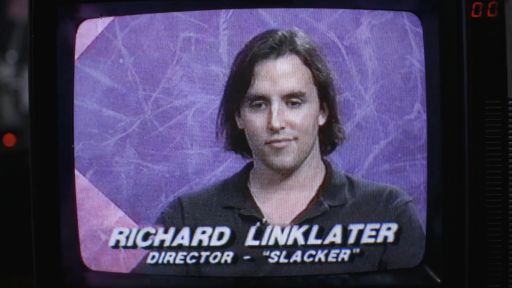

It’s hard to remember how many times filmmaker and Austin Film Society Artistic Director Richard Linklater has been on the cover of The Austin Chronicle. This is not even to consider how many more times we’ve featured interviews with him, articles on him, and pieces by him (as well as film reviews and previews). Many would immediately claim that the first Linklater cover was for Slacker, when Chris Walters’ story actually began on the cover (accompanied by photos) of Vol. IX, No. 47, July 27, 1990. This helped the film kick off its almost three-month successful run at the Dobie Theatre. The run ended only because Slacker had been picked up for distribution by Orion Classics and they wanted to take it out of the Austin market until the national theatrical release in 1991.The Cinema-Fist, Sam Fuller cover of Vol. VI, No. 14, March 27, 1987, is worth thinking about in this context. This was in conjunction with a six-week film series featuring three films by Fuller and three by Robert Aldrich, co-sponsored by Austin Community College and the Austin Film Society. ACC film teacher, well-known writer, and occasional Chronicle reviewer, the late George Morris wrote the story “Cinema Fist Part One: Samuel Fuller.” In April, “Cinema Fist: Part Two” featured three films by Robert Aldrich. Underworld, U.S.A., The Crimson Kimono, and Verboten! were being shown, all good Fuller films though not among his greatest works. (If only George were still alive to argue that point. What joy would that engagement be!)

The “Cinema Fist Part One” cover was of Sam Fuller and by Dan Kratochuil, Rollo Banks, and Rick Linklater, who was, of course, the series co-sponsor by way of the Austin Film Society. Conflict of interest concerns were negligible when it came to celebrating the genius of Fuller. No matter how you want to conceptually score it then, this was the Chronicle’s first Linklater cover.

The following piece on first meeting Rick Linklater and Lee Daniel, the founding of the Austin Film Society, and the making of Slacker is reprinted (slightly revised) with permission from ARTL!ES No. 37, Winter 2002-2003.

In the fall of 1985, Lee Daniel and Richard Linklater decided to promote two shows of avant-garde/experimental films, feeling there no longer were any screenings of such works on any kind of regular basis in Austin. Video had arrived, adversely impacting the UT campus film series. Already gone was CinemaTexas, the Radio-Television-Film department’s graduate-student-run film society, which had shown films to complement classes, Westerns for a course on Westerns, Italian Neo-Realist works for one on that film movement, etc. The remaining campus series scaled back the diversity of their programming, eliminating all but the most reliable Hollywood and foreign classics and most cult films. Daniel and Linklater were determined to show films the way they were meant to be seen, on the big screen, so rather than badger or complain, they decided to try their hands at programming.

They talked Scott Dinger of the Dobie Theatre into letting them use one of his screens. They then approached me about getting free advertising in The Austin Chronicle. Linklater has written that “had not the Chronicle given us a free ad for the show, we wouldn’t have gotten far. I remember someone pointing out Louis Black to me at Liberty Lunch. I approached him between sets and told him how moved I was by his Sam Peckinpah obituary tribute, a recent cover story. I also told him what was going on with the films at the Dobie, and he said to come by the office. They were all very appreciative and supportive of our efforts. The core group at the Chronicle had all come out of CinemaTexas/UT graduate film program and loved movies more than anything.”

My memory is different in that we indeed met at Liberty Lunch with Rick complimenting my Peckinpah obit, but that it was some months before the screening. We had run into each other occasionally, usually talking movies, over the months, so that by the time he asked for the ad, we were well acquainted. Backing up my version is that the Peckinpah story ran in the Jan. 11, 1985, issue of the Chronicle, and the two programs were on Oct. 4 and 5 and Oct. 24 and 27, 1985.

These screenings led Linklater, Daniel, and friends to form the Austin Film Society. (Rick’s quote above was from a 1995 monograph celebrating AFS’s10th year.) In order to qualify as a nonprofit, they needed a board. I was asked to be on it, though for most of the first decade we didn’t meet — Rick just came by once a year asking me to sign papers.

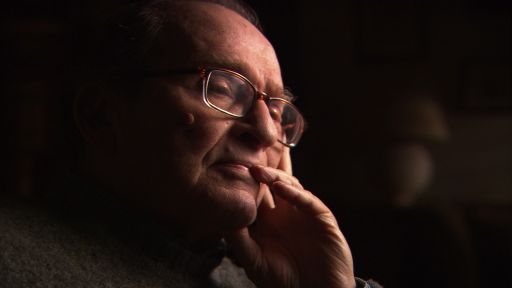

During the late Eighties, the Chronicle gang would often run into Rick, Lee, and others, including D. Montgomery, Clark Walker, and Anne Walker-McBay at screenings and at clubs. Our most notable meetings were at parties thrown by George Morris. A native Austinite, Morris had lived in New York for many years before returning here. There he hung with the film crowd, writing on film. On occasion, George wrote for the Village Voice, had been film reviewer for Texas Monthly (while living in NYC), as well as having written a well-respected book on Doris Day. Before we had even thought about beginning the Chronicle, the CinemaTexas gang had become aware of him for having authored the only serious work we could find on director John Stahl in Film Comment. Morris was a die-hard auteurist who could easily be baited on directors he loved. By dismissing Blake Edwards’ The Party, dissing Darling Lili, and mocking the third of S.O.B. I really despised, I could get him sputtering. Current AFS Director of Programming Chale Nafus, then an Austin Community College professor (referred to by Rick as “The only film teacher I officially ever had”) was not only intimately involved in the Film Society but, socially, was a key participant in these parties. There would be Film Society, CinemaTexas, Austin Chronicle, ACC, UT RTF folks, along with members of bands like the Butthole Surfers, film gluttons all, talking breathlessly nonstop about films, arguing over directors and specific works. The range included everything — silents, experimentals, Soviet films, French New wave, the young German Cinema, independent American movies and, of course, mainstream Hollywood movies (this was a very director-friendly crowd with a comprehensive knowledge of American film). Gibby of the Buttholes often talked about the most unusual films: weird movies of a guy shooting 20 feet of colon out his ass and the like.

Rick would often come by the Chronicle to bum ads for AFS screenings and to politic for editorial, often successfully. We would all sit around talking film. Occasionally, he would hang out for quite a while, hoping space would open up so we would increase his ad size, even when the issue’s production was getting a little too intense. On more than one occasion, I lost patience and threw him out of the office screaming at him. I wish I could claim that this was in some way unique but unfortunately loud, angry, and emotionally wired was my norm at the time. During these first years we thought of Rick as an inspired booker, but not really a filmmaker. Having come out of RTF graduate school with a whole group of film history, theory, and criticism folks, Rick and friends seemed to be of that ilk, though not even academics.

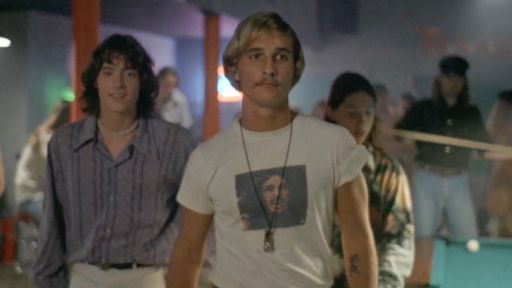

In 1989, Rick asked if I would be in a film they were making. I knew they had shot some Super-8 shorts, but I wasn’t really intimately involved in the group. In fact, it was only years later I found out they had already shot It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, a Super-8 feature. By then I was married, living in the house my wife had from before we were married. I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it. I had been in two feature productions as an extra, and more than a handful of student shorts. These always turned out to be long and boring shoots. Rarely were the scripts finished, never that I can remember did a director know exactly what they wanted, and always after the semester-end RTF film students’ finished-project screening, they disappeared. I had sworn off appearing in films years before. Worse, since Rick and group weren’t even students I was sure the film would never be finished (the mortality rate was ridiculously high among the longer, more ambitious film-student works, even when being done for credit). At this time Rick’s standard look was Prince Valiant haircut, shorts, T-shirt — again, not a confidence inspirer (interestingly, the look didn’t change for years, staying the same through his first four or five films, but that’s a different story). So when asked, I wavered. When Rick called to remind me of the filming and give me the time I needed to show up, he made it even easier, adding that it was only a line, and if I didn’t come he could always get a crew member to do the part.

At just about the last minute, I thought what the hell, threw on a black T-shirt, and drove down to the G&M Steakhouse on North Lamar. Outside was a van with equipment in it and a few cars parked around. I went in; tracks for a dolly holding the camera had been laid down the narrow width of the restaurant, running parallel to the counter. The lighting was mostly set, and we were soon ready to go. It was great; I knew most of the crew and was happy to see them.

The scene began with the Traumatized Yacht Owner (Lori Capp) sitting at the counter muttering “Quit, quit, you should quit. … never, never … you should never, never, never, never, traumatizing … you should never, you should never …”

I’m sitting at a table holding a newspaper; more than reading, I’m crazily gripping it as though I want to tear it apart and devour it.

Happy-Go-Lucky Guy (Frank Orrall of Poi Dog Pondering) comes in; the cranky cook asks, “What do you need?” Happy-Go-Lucky Guy answers, “Uh, can I have a cup of coffee?” and then sits down at the table in front of me.

“Traumatized” is muttering “you should, you should, you, you should, should never traumatize a woman sexually. …”

Sitting under a sign that says “Plate ‘O’ Shrimp” in my role as the Paranoid Paper Reader, almost ripping the paper, I offer my two lines as psychotically as I can, addressing Happy-Go-Lucky Guy at the next table, “Quit following me! (pause) You heard me, quit following me!”

Rick had me do it a couple of times, trying to get me to look and sound even crazier. My part in the shoot took about an hour and a half. I left in a great mood. It was quick, fun, and with people I really liked. If I thought about the film at all after that, it was just expecting it would never be finished.

Sometime during 1990, Rick handed me a videotape of the finished version of the film. The editing, lighting, and naturalistic cinematography really interested me. I admit, though, that after watching the first few minutes and not thinking it was about much, I fast forwarded through the rest (except for my scene). I was especially fascinated by the long takes, admiring how they were shot, wanting to see how they were edited together, so I went through it several times. But I never really watched the film for its story.

Rick had arranged for the film to play at the Dobie in July 1990, with Dinger saying the length of the run would be determined by how well it did. The Chronicle, with Slacker on the cover, featured a story about the film by Chris Walters. The first 22 shows sold out; the film ran for almost three months, and the only reason it stopped was it had been picked up for national distribution by Orion Classics, and they wanted to control all theatrical screenings. Honestly, it wasn’t until I read Walters’ piece that I had any idea the film was about something. Watching the tape all the way through after reading the piece was the first time I realized how special it was.

Without question, the most important moment in Austin filmmaking history, even more than the story of the making of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, was Rick Linklater’s decision to stay in Austin after Slacker and not move to L.A. Given his socially conscious drive, Linklater not only inspired filmmakers across the country, he united the Austin film community into a cohesive cultural force.

CODA: TORONTO, SEPTEMBER 2003

Chronicle Film Editor Marge Baumgarten and I are at the Toronto International Film Festival, where The School of Rock, Rick Linklater’s newest film, is scheduled to be a gala presentation. Only Rick won’t be there as he is in Paris filming a sequel to Before Sunrise. When I mention this to one of the TIFF directors he seems quite surprised, though Jack Black and much of the rest of the cast are still going to be there. Paramount schedules several extra screenings of the film for critics held at non-Film Festival theatres elsewhere in Toronto. Rather than tackle the gala, we decide to attend one of these.

On the cab ride up to the theatre, Marge assures me there won’t be many critics there because it is too far away. She proves more than correct when we are among the half dozen critics seated in the three or four saved, although empty, rows. Every other seat in the theatre is full, while outside is a line of folks hoping to get in to watch The School of Rock. Gradually, the critics’ seats are released, and the theatre is completely full when the film starts.

The screening is a huge success. It is great to see the film with nonindustry folks. They love the movie, laughing and clapping. The ending credits are shown over a scene featuring Jack Black; for one of the few times I can remember not a soul leaves the theatre until the credits are completely over and the lights come up. We sure hope that The School of Rock is going to be a hit, but we know for certain that it is a wonderful, funny, rock & roll-loving film.

Funding for Richard Linklater – dream is destiny is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.