The following essay on the life and achievements of Bill T. Jones, written by John Rockwell, was presented in 2010 when Jones was bestowed with the Kennedy Center Honors.

Our politicians toss around the term “the American Dream” loosely these days, but Bill T. Jones has lived that dream. Sometimes the dream has seemed more like a nightmare, but the larger arc of his life looks triumphant, a genuine fulfillment of American striving and ambition, very much in the real, waking world.

Jones rose from being the 10th of 12 children of migrant farm workers to one of the most notable, recognized modern-dance choreographers and directors of our time. Through HIV and AIDS, which claimed the life of his longtime partner, Arnie Zane, to controversy and anger and acceptance, Jones now sits on top of the world, even if that world still sometimes seems to him unfair and unjust.

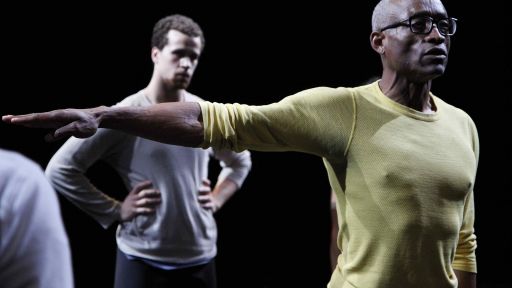

Now pushing 60, he remains a remarkably handsome man, sinewy and commanding with an angular face that might seem to belong on a coin, or a medallion, or Mount Rushmore. Back at the height of his dance career in the 70’s and 80’s, he was one of the most beautiful men many of us had ever seen. As late as 2004, the Guardian in London called him “a dancer of extraordinary grace and beauty.” But even then, he had already transcended physicality into the realms of political statement, moral fervor and intellectual contemplation. “Part showman, part philosopher,” the International Dictionary of Dance called him.

From his earlier dance experiments to his political frescos of “Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” of 1990 and “Still/Here” of 1994 to his more recent meditations on Lincoln (and Martin Luther King and Barack Obama), from dance to Broadway with “Spring Awakening” and “Fela!,” Jones has garnered an overflowing armful of honors and awards and honorary doctorates. Now he is a Kennedy Center Honoree, but before then there was a MacArthur Award in 1994, numerous downtown dance and performance Bessie awards, the Dorothy and Lillian Gish prize in 2003 and Tonys in 2007 and 2010.

Jones was born on the day after Valentine’s in 1952 in Bunnell, Florida; the T either stands alone or for Tass. His parents, Gus and Estella, picked fruit there, traveling north every summer to Steuben County in upstate New York for the potato harvest. “I was a child of potato pickers who wept at the Civil Rights Act of 1964, who had pictures of Lincoln, Kennedy and Martin Luther King on the walls,” he wrote. “I was 12 when I saw the March on Washington with this beautiful orator, Martin Luther King, speaking and holding the world. There was hopefulness. I wanted to be part of that.”

He was raised in Steuben County and starred as a track athlete in high school. At the State University of New York in nearby Binghamton, which he attended on a special program for underprivileged students, he began to discover himself – as a gay man, as a modern dancer and as a performer and provocateur. “When I took classes in West African and African-Caribbean dancing, I started skipping track practice,” he recalls. At college he met Zane, a short, white, Jewish student devoted to photography, cross dressing and Jones, so much so that he too began taking dance classes. “We were shocking even for the Art Department,” says Jones.

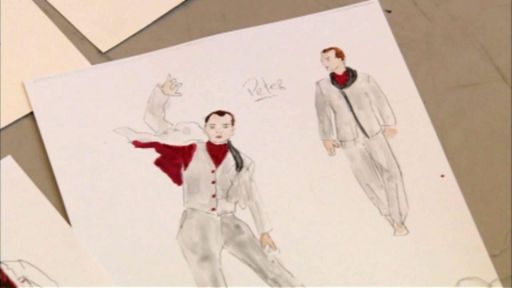

After a year in Amsterdam, Jones returned to Binghamton and helped start a company called the American Dance Asylum. Jones worked in a laundry, Zane as a go-go dancer. From the first, they concentrated on a multimedia approach that transcended pure dance, exploiting their gayness and their physical differences. “Arnie was a photographer, he was painting making water-colors, I was writing poetry, I would sing, talk and dance onstage, all at once.”

They moved down near New York City in 1979, and in 1982 formed the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. “Mismatched physically, they are marvelous foils for one another,” wrote the critic Tobi Tobias. In 1983 they began their long, not-yet-ended (except for Zane’s death in 1988) relationship with the Brooklyn Academy of Music. “Intuitive Momentum,” a collaboration with the jazz drummer Max Roach and the painter Robert Longo, was part of the very first Next Wave Festival. Zane was diagnosed with AIDS a year later, and by 1988 Jones, himself HIV-positive, was on his own.

But the ensemble, to this day still named the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, did not die. While together Zane was perceived as more the conceptualist/choreographer and Jones the dancer, though they shared in everything. Jones quickly proved himself fully adept in the conceptual and choreographic realms. The critic Deborah Jowitt had once described the Zane-Jones partnership as “cool form with hot content.” Jones’s dance style now embraces both extremes, a determinedly eclectic blending of Afro-American folk and popular dance, modern and postmodern dance, ballet and contact improvisation. If some fault him for a lack of a distinctive movement style, he more than makes up for that with his theatrical and political ambitions. The company has always deliberately sought the widest possible diversity of races, styles and body types.

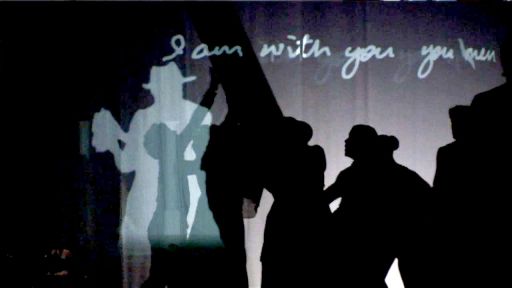

Jones’s dances in the years following Zane’s death focused on political, racial and social issues, and established his reputation for anger. He and his handlers have struggled with some success more recently to modify that image, but it did correspond to his major work in the early 90’s, as well as to his sometimes testy behavior in public forums. Chief among those works were “Last Supper,” a BAM Next Wave commission from 1990, and “Still/Here” from 1994, the result of a residency at the venturesome Lyon Opera Ballet in 1994, which also appeared at BAM. “Last Supper” was an autobiographical fresco blending Harriet Beecher Stowe with Martin Luther King, Estella Jones chanting and, at the end, 60 naked performers onstage. Jones prefers not to dwell on the controversy now, but the critic Arlene Croce’s famous non-review of “Still/Here,” in which she proclaimed the work unreviewable as “victim art,” still rankles. Time Magazine did put him on its cover, and he won his MacArthur “genius” grant.

Jones has continued to make dances that draw attention and lead to worldwide tours, often with décor by his partner Bjorn Amelan. These have included “We Set Out Early…Visibility Was Poor” in 1998, “The Breathing Show” in 1999, a revival of “Still/Here” in 2004, “Chapel/Chapter” in 2006 (a particularly moving, less politically overt interweaving of three stories of murder and death), “A Quarreling Pair” at BAM in 2008, based on a Jane Bowles story of two middle-aged sisters, and a string of Lincoln-inspired dance-theater pieces culminating in “Fondly Do We Hope… Fervently Do We Pray” in 2009.

In 1991, Jones eased into a second, parallel, increasingly visible career as a choreographer and director for theater, musicals and opera. First was “The Mother of Three Sons,” a lurid opera conceived by him with music by the jazz composer Leroy Jenkins, seen in New York, Houston and Munich. The next year he directed Weill’s “Lost in the Stars” for the Boston Lyric Opera, in 1994 a Derek Walcott drama at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, and in 1999 a collaboration with the opera singer Jessye Norman. But his two biggest theatrical projects thus far have been his choreography for the musical based on Frank Wedekind’s “Spring Awakening” on Broadway in 2006 and his direction and choreography for the musical “Fela!,” about the Nigerian musician and Messianic politician Fela Anikulapo Kuti, first off-Broadway and then on Broadway, where it’s still running. “I was afraid my work was reaching sameness,” he said, “and Broadway made me fresh.”

All kinds of projects and performances remain on Jones’s calendar. So it came as a surprise to the dance world when a merger of his company with the venerable downtown Manhattan Dance Theater Workshop was announced earlier this year. “I am not usually a pleasant person to work with,” he conceded after the announcement. “Everything is do or die for me.” How the merger will play out, for the company and the workshop, remains to be seen. What is incontestable is that Jones’s long road, from potato-picking to international star, has no end in sight.

– John Rockwell