Here—or, more indelibly, heeeeeeere—is John William Carson who, on May 22, 1992, did for the very last time what nobody else has ever done better (or with greater panache and seismic authority), from behind or in front of any desk, performing invaluable national service nightly on a television screen.

There, all cool and bright, he was a man named Johnny (never John, which he had always been—even in boyhood—and would remain to those who knew him best). Moreover, he was a man of unprecedented omnipotence for his line of work: It was October 1, 1962—just a few weeks before his thirty-seventh birthday—when Carson commenced his fabled epoch of hosting The Tonight Show, NBC’s venerable bedtime franchise. Across the next 29 years, 7 months, 3 weeks total, he rose to reign iconic as the smooth midnight sentinel king whose political japes and cultural enthusiasms mightily swayed popular taste at whim or wink. (The Carson wink, incidentally, would be the last best wink known to humankind; it transmitted, among other things, surefire stardom to aspiring personalities, especially comedians, and privileged co-conspiracy to regular viewers who became his spontaneous partners in sly mockery. He made high art, too, of the silent sidelong glance into whatever camera lens available—his eyes impishly saying everything he chose not to speak aloud, only saying it louder.)

Patriarchal broadcast lion Walter Cronkite, a.k.a. the Most Trusted Man in America (arguably a time-share mantle owned in equal part by Carson), once summed up the long-shadow legacy of the late-night stalwart as that of “a cool kid from Nebraska with a cockeyed smile who became the most durable performer in the whole history of television.” True, like sun and moon and oxygen, Johnny Carson was there always, steadfast and suavely reassuring; even when he took time off for restorative behavior, his presence loomed while guest-hosts tarried gamely at his formidable desk. That he was watched and collectively experienced by an impossibly vast constituency during hours most intimate and vulnerable only deepened his American meaning. (Gravitas personified: Halfway through his run he was drawing an average of 17.3 million faithful, whereas today’s comedy night-boys are lucky to lure more than five million captive, albeit in a wholly different cable-splayed universe.) “We are losing a continuum,” fretted critic Tom Shales twenty years ago, evincing the groundswell of abandonment angst burbling as Carson’s final Tonight Show broadcast approached. “For nearly thirty years, at a tender and delicate hour . . . he has cured innumerable cases of the blues, alleviated countless depressions, mercifully interrupted millions of arguments. . . . It’s natural to panic.”

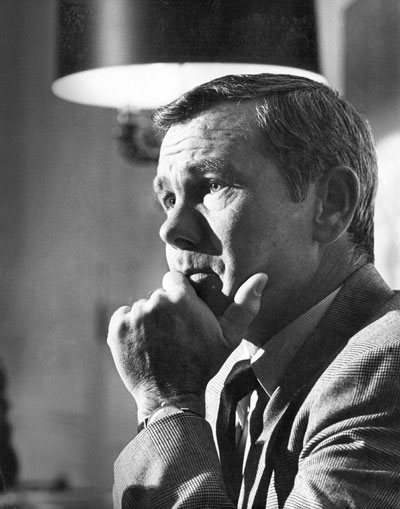

Johnny Carson, circa 1967. Credit: Courtesy of Omaha World Herald

Carson was, for certain, the bump in the night that delivered hope and perspective. His opening monologues (ever his pride and joy) navigated us through seven presidential administrations, rasping out the perfect pitch of populist incredulity, always with subtle precision; the Carson version of history, as it occurred daily, anchored mass sanity funniest in a world gone perpetually mad. Also, like no one else in a latter century lifetime, his was the last face flickering onto the brain before so many billions of slumbers, thus launching the dreams of generations. (Medical science, no less, immortalized him by naming in his honor a form of temporary one-eyed blindness caused by burrowing the other eye into a pillow while nodding off watching TV: Carsonogeneous Monocular Nyctalopia.) Indeed, the great director Billy Wilder once gratefully proclaimed him “the Valium and the Nembutal of a nation.” Only two weeks before the king’s abdication, Frank Rich put it this way in The New York Times: “The actual content of a Carson show did not matter. At a time of anxiety, who cares about the color and material of a security blanket?” The unassailable upshot: No other performer had ever felt so dependably essential to his country’s sense of well-being—or, quite likely, would ever wish to.

Famously the most public of private men and vice-versa (which was only part of his peculiar genius for longevity), he could joke, “I will not even talk to myself without an appointment.” While openly on display for three decades of nocturne, he was at the same time barely spotted anywhere outside of television screens—which was how he liked it, then and ever after. (His gift for hiding in plain sight didn’t diminish during the intractably cloaked thirteen-year retirement he spent relishing spotlight-free living; Garbo and Salinger had nothing on his powers of ordinary civilian invisibility.) Still, a silken aw-shucks Everyman exemplar—confident and dashing and eternally boyish—he was also slippery as the night is long, never easy to pin down, yet always an affirming presence to behold whenever he could be beheld: “And that’s why Carson has no equal—not even Cary Grant, whom he resembled in shyness, smartness, and lethal counter-punching style—as a model of what an American man might be,” wrote David Thomson, the fanciful British expatriate film scholar. “He came away from that scrutiny as both an American ideal and a mystery man; agreeable and withdrawn; good company and intensely alone; attractive yet cold . . . always there, never graspable. . . . I feel he stayed unknowable so as to be seductive, to stay there, on TV.” Carson, the staunch Midwestern pragmatist, would simply ascribe all that to good business sense: “Always leave them wanting more,” he would genially repeat to quell chronic speculation about his personal world—all evasive twinkle, all the time.

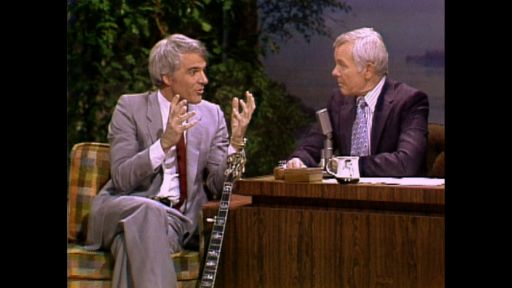

Johnny Carson, circa 1970s. Credit: Courtesy of Carson Entertainment Group

“Johnny packs a tight suitcase,” was the definitive Carsonian metaphor coined by Ed McMahon, his Gibraltar-like sidekick and irrepressible foil since 1958 when they joined disparate forces in New York on the hit afternoon ABC quiz-fizz Who Do You Trust? That glib daily showcase would four years later springboard them (how could he not take Ed?) to The Tonight Show, which beamed from NBC’s 30 Rockefeller Center, Studio 6B, during Carson’s first decade of enthronement preceding its permanent shift westward to California. (Meanwhile, McMahon’s nightly vowel-elasticizing host introduction—“Heeeeeeeeeere’s Johnny!”—would be consecrated in 2006 as the number-one ubiquitous television catchphrase ever, according to the TV Land cable network.) But the Carson personal world was knowable enough—and gingerly becomes only more so in his majestic if complex mortal wake. Devotees had long known, for instance, that he married four times and divorced thrice from a trio of wives with ridiculously similar first names: Joan Wolcott (his University of Nebraska college sweetheart who bore him three sons while absorbing all of his career birthing pains as well), Joanne Copeland (whose impassioned loyalty propelled his early stratospheric Tonight Show stewardship), and Joanna Ulrich Holland (who gracefully enhanced and broadened his relocated lifestyle of California kingliness). He took his final and considerably younger bride Alexis Mass in 1987, making theirs his longest turn at wedlock, inevitable bumps in the last years notwithstanding. “Marriage takes a lot of work,” he once said, certain of his limitations. “Some fellas have a proclivity for that, and some can make model airplanes . . . I do well with this show.”

Most viewers also knew that as a kid he learned magic (enter The Great Carsoni!), largely to overcome shyness, and never stopped creating illusions, especially when trapped at parties (he went nowhere without a deck of cards) or when making hypnotically irresistible television after dark. He entered existence on October 23, 1925, in Corning, Iowa, the middle child of Homer L. (“Kit”) Carson, a kindly power-company yeoman, and the former Ruth Hook, an exacting woman of refinement with thin patience for her future-famous son’s strivings. When John was eight, the family settled in Norfolk, Nebraska, where just under a handful of years hence he snagged a friend’s magic-manual and would, at age fourteen, as Carsoni, earn his first performance fee—three dollars—from the town Rotarians. Thus, as Time’s Richard Corliss saliently suggested, he’d “found within himself the secrets of conjuring—misdirection, poise, timing, a commanding personality—which are also the secrets of standup comedy.” All pieces more or less fell into place thereafter with haphazard surety. Starting in Omaha, where TV arrived the same time he did, at station WOW (true), he began a life of hosting that led him to gilded Los Angeles and local acclaim on KNXT, the CBS affiliate, with quirky novelty programs that eventually beguiled the network to shove him into his own national primetime Thursday night half-hour, The Johnny Carson Show (debut date June 30, 1955), an ongoing experiment in sketch-and-song confusion that crashed after 39 weeks. His promising glimmer resurfaced and shone at last some 18 months later in New York, helming the game show originally (if ironically enough) called Do You Trust Your Wife? before the titular Trust question was generalized ungrammatically.

“I turned The Tonight Show down the first time it was offered to me because Who Do You Trust? was very comfortable and quite easy,” he recalled sometime after he changed his mind, agreeing to replace the legendarily manic sensation Jack Paar who’d worn of the relentless grind not yet five years into his own jangly reign supreme. “My first reaction was, ‘Why do you need that kind of trouble?’ Then they came back [three weeks later], and I said, ‘If you’re really going to take a shot at it, if you really want to entertain, you ought to grab for all the marbles or get out of the business.’ The more I thought about it, the more I became convinced that Tonight was the only network show where I could do the nutty, experimental, low-key thing I like best.”

Forty years after having first seized the night to do what he and his country liked best, and one decade after he had quit, I found myself the beneficiary of his lively company for a long red-wine-sipping lunch, as he submitted to the lone magazine profile (or media visitation of any sort) since the early onset of his retirement vanish. “I think I left at the right time,” he told me that January afternoon in 2002, which also turned out to be almost exactly three years to the day when emphysema took him forever (January 23, 2005). “You’ve got to know when to get the hell off the stage, and the timing was right for me.” (IT’S ALL IN THE TIMING, I knew, was his life’s credo as well as the hand-stitched mantra on a needlepoint throw pillow he treasured.) Unavoidably, among the grand tales and meandering topics that flew from him that day, he gently groused only a little about being asked constantly whether he missed the work whose standard he’d made unmatchable. With a shrug and a whiff of quiet satisfaction, he repeated the three-word response he gave whenever the question arose: “I did it.” Who could argue otherwise?

By Bill Zehme, author of Carson the Magnificent: An Intimate Portrait (Simon & Schuster).