Written by Director and Producer Nancy Buirski

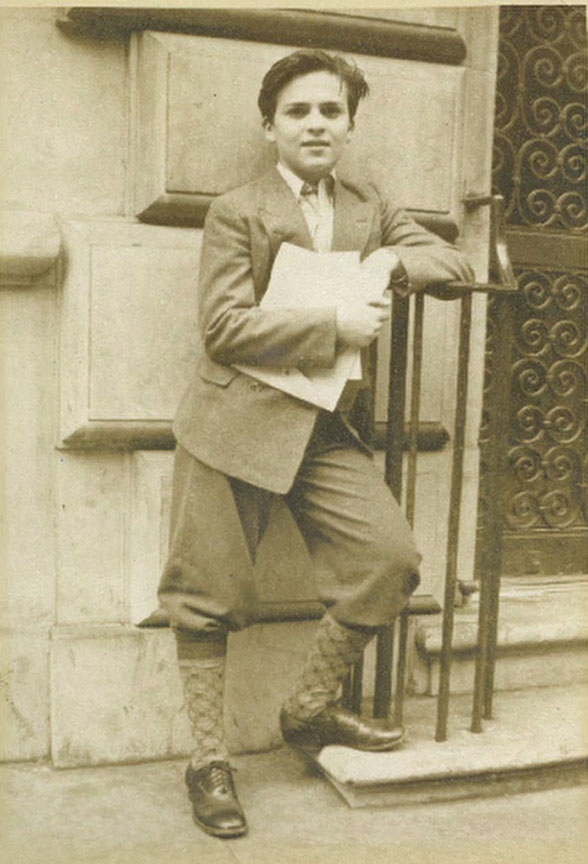

Lumet’s own story began in Philadelphia in the early 1920s. His father, Baruch Lumet, had escaped to America a few years earlier to avoid being drafted into the Polish army, which often forced Jews to serve on the front lines in the battle against Russia. Baruch sent for his wife and daughter a few years later, and in June 1924 Sidney Lumet was born. Two years after that the family moved to New York City, where Lumet’s father hoped to pursue an acting career.

Lumet as a child.

Like many impoverished Jews in 1926, the Lumets settled in tenement housing on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, home to generations of Jews who had left Eastern Europe in search of a better life. Before the restrictive immigration laws of 1924, more than 5,000 Jews lived in an area that encompassed two square miles, dwarfing nearby Little Italy and Chinatown.

By the time the Lumets arrived, conditions had improved but the neighborhood was still known as the Jewish Ghetto. Those who could afford to move out did so. While the Lower East Side had ceased to be the hub of Jewish immigrant life, it had become something much more powerful – a nostalgic touchstone that one only had to mention by name to understand the essence of a time and a place and a people – a primary site of Jewish American identity. For the Jews who still lived there when the Depression hit it also became the very definition of poor. The Lower East Side, which alone had as many as 50 bread lines, became one of the most impoverished areas in the country.

Streets smarts on the Lower East Side were hard earned, and one’s affiliation with the neighborhood was life-long. It was an “ugly, dirty, and dangerous place for children. Most parents worked, so kids taught each other lessons about survival and humanity as they confronted poverty and other privations, as well as ethnic gangs from nearby neighborhoods. “It might have been dangerous to go to the next block and an Italian kid would beat me up, but on my block it was all Jews, all the time,” Lumet said. “It provides you with a standard of behavior that a mutual consideration, mutual teaching, is a way of teaching you not to be selfish. And, even though I haven’t lived up to it that well, I must say it’s something that has been with me all my life…no one talked about a moral code. It was just how you lived.”

Lumet grew up in an orthodox household, stern and moralistic. However, his childhood was unusual. Lumet’s father had brought the family to New York to pursue his acting career and Sidney spent much of his time in the theater. He was only four years old when he got his first acting job and by the time he was seven he and his family had a regular gig on a radio soap opera called The Grandfather from Brownsville. It aired on WEVD, 15 minutes a day, five days a week, and was written and directed by his father. The family earned 35 dollars a week, about ten dollars more than the average family on the Lower East Side.

Still, Lumet recalls extreme poverty, which he said puts one in touch with social issues. As a child, he witnessed the daily struggles of good people in undignified conditions; police officers stealing pennies from the street, domestic disputes in families where tensions were high. Lumet’s family moved once a year to save a month’s rent and bought clothes too big in order to last longer. Lumet understood at a young age that his work as an actor put food on the table. It established in him a work ethic that became a hallmark of his career. His long rehearsals and preparation before filming were legendary. For Lumet, discipline and hard work were not just admirable habits, but reflected the quality of your character.

Working Class Roots, Community

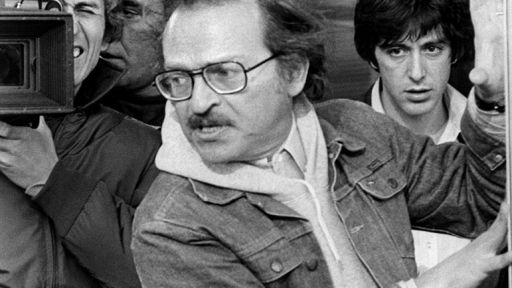

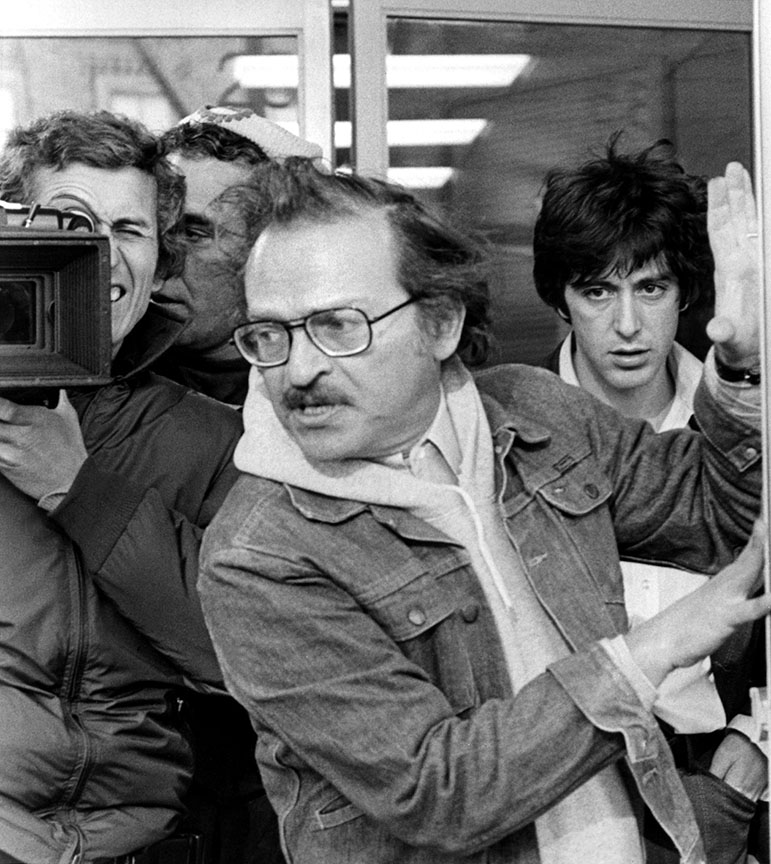

DOG DAY AFTERNOON, Sidney Lumet, Al Pacino, 1975

New York Jews fostered deeply held beliefs about community responsibility. Even years before the Depression, privately funded Jewish mutual aid societies offered health and life insurance to residents. “That kind of mutual protection created a sense of… knowledge of dependency which is to me a very moving idea,” Lumet says. “I am not alone; I am not out on my own. I owe something to other people. I am dependent on other people. We are a society, not an individual fighting the society. And that communal sense explains a great deal about Jewish life in New York particularly.”

One of the most remarkable mutual aid societies was the International Worker’s Order, established in 1930. The IWO was affiliated with the communist party, whose political ideology at that time made sense to working class people and intellectuals who were critical of out-of-control capitalist’s success and their indifference to the hardships of most Americans. The IWO started as a Jewish insurance organization that supported schools that taught Yiddish and camps, like Camp Kinderland, which Lumet attended when his father was a drama counselor. As part of the Popular Front social movement, the IWO offered low rate insurance to people of all races and ethnic backgrounds and became a multi-ethnic, multiracial organization that supported the working and cultural life of all its members. In 1947 its successful schools and cultural lodges, caught the attention of the Attorney General and the IWO was included on a list of subversive organizations. “The IWO, which was ‘the largest, most successful left-wing organization in modern American history’ was a particular target; and the only court case in American history in which an insurance company was prosecuted for its political views,”_ writes Michael Denning in The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century.

The New York of Lumet’s youth was a working class town steeped in the national fight for workers’ rights and racial and religious tolerance. These were the years when thousands of people gathered for annual May Day marches. Lumet marched with his family as a child and then later with Actors’ Equity. “It was a lovely feeling because there was a great feeling of protection because of the mutual dependency,” Lumet said. “The idea of a society built on mutual dependency came as such a natural thing to Jews, who were doing it already on a social level. They could not do it on an economic level. So it really formed a basic vulnerability to injustice and a reaction to injustice that is still part of me today.”

Yiddish Theatre and Literature

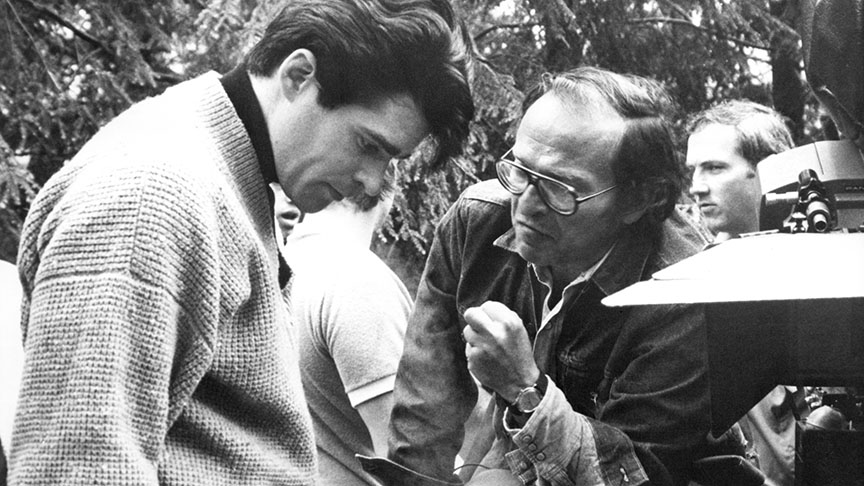

Prince of the City (1981)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Shown on the set from left: Treat Williams, Sidney Lumet

For a Jewish actor in Manhattan, the center of creative expression in the early 1930s was Yiddish Theater. The shows were unsophisticated and melodramatic but beloved. Theaters were plentiful and tickets were cheap, sometimes sold in large blocks and passed out to business patrons. Yiddish Theater’s importance at that time cannot be underestimated. The stories were needed as much as enjoyed, as they mirrored concerns of the immigrants’ lives – assimilation of children through mixed marriages; fear of poverty; longing for loved ones left behind in Europe; anti-Semitism, and the frustrations of trying to understand and cope with American society and values.

As a child, Lumet was immersed in the world of theater, where his father lived and worked, and he absorbed it all: the words, the staging, and the storytelling. The theater gave him an escape from life in the ghetto and introduced him to a more sophisticated expression. Lumet recalls “the wonderful adventure” in his family’s apartment, listening for hours as his father rehearsed the writing of Joseph Opatoshu and Shakespeare (which he first heard in Yiddish). At a young age he developed a deep respect for the language and rhythm of great writing.

Theater remained a rich source of material for Lumet once he began making movies. He often adapted scripts from stage to screen, exposing larger, more diverse film-going audiences to the important literary works of playwrights and screenwriters such as Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, Anton Chekhov, Paddy Chayefsky and David Mamet. He also worked with authors such as E.L. Doctorow, Peter Maas, Gore Vidal, John Le Carré, and Larry McMurtry adapting their novels to the screen.

One of his earliest films introduced filmgoers to Eugene O’Neill’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, A Long Day’s Journey into Night, starring Katharine Hepburn. The play is a family drama—a theme Lumet would return to often—centered on one day in the life of a family crumbling under the weight of addiction, isolating self-interest, and family dysfunction. “Probably the most brilliant adaption of a play” wrote Robin Bean in Sidney Lumet: Interviews, edited by Joanna Rapf. Shot, “word for word almost entirely on one set without any ‘expansion’ or opening out of the story…he uses his camera to intensify the atmosphere evoked by the author’s dialogue, examining in minute detail the character, feelings and reactions of the Tyrone family.”

Actors, Influences of the Group Theatre

PRINCE OF THE CITY, from left, Treat Williams, director Sidney Lumet, on location in New York, 1981, ©Orion Pictures. Courtesy: Everett Collection

In 1935, 11-year-old Lumet made his Broadway debut in a play called Dead End, written by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Sidney Kingsley. Lumet quickly became a child star, appearing in at least 14 plays. His skill working with film actors as a movie director no doubt began with this early exposure to the talent around him, which included the actors and playwrights in the Group Theatre, of which Kingsley was a member, as was Lumet briefly. The Group was an historic and influential ensemble of actors and playwrights, whose idealistic structure was based on a popular Soviet theater model. Members were deeply committed to the idea of realism, in writing and performance, and to art’s social relevance. It incubated Method acting, as well as important playwrights and actors, including Clifford Odets, who wrote Waiting for Lefty, and Elia Kazan, whose career would travel a similar trajectory to Lumet’s but with a very different flavor.

Known in the industry as an actor’s director, Lumet had a reputation for drawing out great performances in his films. During his long career he worked with the most accomplished actors in motion picture history including: Marlon Brando, Katharine Hepburn, Al Pacino, Henry Fonda, Rod Steiger, James Mason, Sophia Loren, Vanessa Redgrave, Paul Newman, and Sean Connery.

Lumet said his method involved understanding their fears and insecurities and then establishing a mutual trust that would encourage self-revelation; a very different technique from a director like Elia Kazan, who Lumet says conjured great performances by exploiting those same neuroses. On Lumet’s sets, actors were encouraged to collaborate on their roles, not simply follow his lead, and rehearsals, which Lumet considered critical to establishing trust, lasted up to several weeks before filming began.

According to film scholars, one of the best acting performances in any of his films is Al Pacino’s in Dog Day Afternoon, which earned Pacino, Lumet, and Chris Sarandon Academy Award® nominations. Pacino, a Method actor, had just finished The Godfather II when Lumet convinced him to take on the challenging role of Sonny Wortzik, a morally ambiguous character who attempts to rob a bank on a hot August day. Based on a true story, the film required a sweaty, intense, and sympathetic performance from Pacino, whose character is gay; the robbery intended to pay for his lover’s sex change operation. The film came out in 1975, only a few years after the Stonewall riots had awakened the nation to the struggle for gay rights. The challenge for Pacino was to keep the audience engaged; to not judge Sonny as an outcast but simply as a man who is suffering.

“Talk about radical,” says Lumet. “What could be more radical than a guy robbing a bank so that he can get the money to pay for his boyfriend’s sex operation? The thing that I think makes Dog Day what it is, is Pacino’s performance. Because it could have easily degenerated into a sensational piece,” he says. “We have got to reach, on a fundamental level, into anybody watching this movie, to make them aware of the humanity of these two men. And I couldn’t have had a better person unearth that feeling than Pacino because he is like an open wound up there.”

Lumet elicited a similar performance from Rod Steiger in the 1965 film The Pawnbroker, which garnered the actor an Oscar® nomination. The story centers on a man who survived a Holocaust concentration camp but lost his entire family. He is now living with his sister’s family in New York struggling to find his soul again. The film examines a person’s strength of character, a recurring theme in Judaism, as seen through the stories of Abraham and witnessed by countless stories of Holocaust survivors. “[The] idea of can you survive,” Lumet says. “Can one survive total destruction when you are already dead? That’s the story of a man coming back to life, and the only way you can start coming back to life is through pain

Golden Age of Television

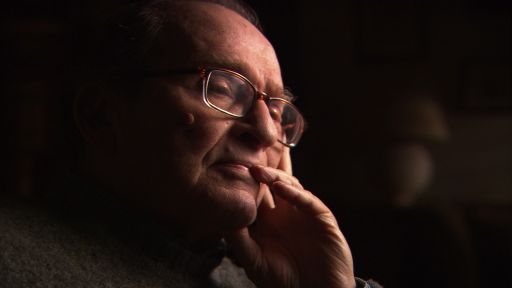

“I consider that fight for your individuality, for me it’s the essence of what life should be about; what a good life should be about.” – Sidney Lumet

THE FUGITIVE KIND, Anna Magnani and director Sidney Lumet on-location, 1959

Around 1950, as the 20th century hit its mid-point, Americans began moving beyond the economic and emotional gravity of the Depression and WWII. Manufacturers rolled out more televisions, a luxury during the war years, and by 1948 about 2.6 percent of U.S. households owned a set. In five years that number hit 50 percent. In 1953 The Tonight Show debuted, as did Romper Room, and millions of people tuned in to see Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz welcome baby Desi on The Lucille Ball Show. In June, Walter Cronkite anchored coverage of the first worldwide television event: the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Into the exciting young medium of television came a 20-something Sidney Lumet, who had spent time in the Army’s Signal Corp and assumed he would live an actor’s life. However, Lumet was offered a job at CBS studios in New York as assistant director to his good friend Yul Brynner and he suddenly found himself working in live television just as it was exploding with possibility. Lumet had never seen a camera when he walked on the set for the first time. “I didn’t even own a television set. I was totally new to it,” he said. “One of the things that CBS did that was just sensational, when you were an A.D. there they trained you everywhere… God knows how many different writers, production people, video engineers, audio men… the exposure was brilliant.”

His first regular show as a director was the live black and white TV classic You Are There. As with all early TV productions, the crew learned on the job. In this show Walter Cronkite took the audience back in time to critical moments in world history, such as the death of Socrates and the signing of the Declaration of Independence. “The You Are There series is gonna sound ridiculous to most people,” Lumet said, “and you are allowed a smile, but I promise you it worked like a dream. The show would begin with the anchor desk, just like you would be with an anchor desk today, but in this instance it was Walter Cronkite. It really, in a way, made his career in the big sense ‘cause the show became a big success.”

After a short introduction, Cronkite would cue the audience with what became the show’s signature dramatic lead-in: “All things are as they were then except, you are there!” At that time, Broadway had an abundant supply of great actors with time on their hands every Sunday when theaters were dark. Eager to experience the new medium of television, the actors agreed to receive scripts on Monday and then show up the following Sunday evening for dress rehearsals, followed 30 minutes later by the show’s live broadcast at 6 pm.

Episode one, directed by Lumet, took viewers to the Hindenburg disaster and its smoky crash. Cronkite recalled special challenges of live television. “What they hadn’t figured out was that I was going to be sitting there 15 feet away,” he said. “So here I’m supposed to be in modern times at the CBS studio in New York, and it came back to the final scene with the Hindenburg going down, and I’m breathing smoke. I can hardly get the words out.”

The unforgiving nature and brisk pace of live television sharpened Lumet’s skills at working quickly with multiple cameras, and he eventually took on challenging live TV adaptations of Broadway classics like Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh. His efficient methods became a hallmark of his career as a film director, where he was known for lengthy rehearsals followed by compact shoots, often refusing actors more than one take on set. “It was a baptism of fire and taught him his craft—the ability to work very fast and yet obtain high quality results,” wrote Gavin Smith in Film Comment.

The Blacklist and Radicalism

For people working in the entertainment industry, the excitement of the times had a capricious shadow. The burgeoning of mass media had coincided with the Cold War and the conflict in Korea; soon a fevered anti-communist movement, which had been simmering for decades, became the majority opinion in America. The entertainment industry was accused of being under the sway of communism and exacting a subversive influence over its American audience.

Indeed, leftist politics had long been embraced by many in the industry. Although Lumet was never a member of the communist party, Gavin Smith pointed out in Film Comment, that Lumet and some of

his colleagues constituted, “a Fifties New York new wave generated by TV and shaped by leftist politics and Method acting.”

“Fear is accurate but inadequate,” said Lumet. “It was terror.” Everyone was under suspicion. Colleagues were expected to inform on each other, to give up names, even without factual knowledge. Many, like Elia Kazan, became friendly witnesses for the government. Lumet was accused of attending a Communist Party meeting before the misunderstanding was clarified.

In the midst of this madness, three of Lumet’s colleagues were blacklisted; Walter Bernstein, Abraham Polonsky, and Arnie Mannoff, top writers at You Are There and considered some of the greatest scribes then working in television. They continued working under pseudonyms. Lumet and a few of his colleagues knew about the arrangement but were protected by not being told which writers were writing which scripts. The entire CBS network was heavily targeted. “They were tougher on CBS because their real objective was to break the CBS News department, which under Fred Friendly and Ed Murrow, they considered left wing,” Lumet recalled.

In concert with Edward R. Murrow’s 1954 program on Senator Joseph McCarthy, Lumet and his colleagues used You Are There to criticize McCarthyism. They aired episodes of other well-known examples of intolerance, including the Salem witch trials, Galileo, and John Milton. Walter Bernstein, in an interview with the Archive of American Television, said, “You have to be true to yourself, to what you believe in… You have to have the bottom line. You have to have some place beyond which you know you can’t be pushed. It’s not politics, it’s morality.” Lumet was the first person to hire Bernstein once his name was cleared. They made two films together: That Kind of Woman, featuring Sophia Loren, and Fail-Safe, a cold war thriller.

“Lumet began his career at the height of McCarthyism,” wrote Gavin Smith. “In retrospect, 12 Angry Men was a definitive rebuttal to the lynch mob hysteria of the McCarthy era, and his 1960 adaption of Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending, The Fugitive Kind, added a postscript… Along with Fail-Safe and The Pawnbroker these films are sophisticated ideological critiques of postwar American society.”

By 1955 Lumet was a top director of live TV dramas on shows like Danger. He now had the power to choose his scripts. Many reflected current issues of justice and morality, such as Tragedy in a Temporary Town, a teleplay written for the Alcoa Hour/Goodyear Playhouse by Reginald Rose, with whom Lumet had worked before and would again on 12 Angry Men.

Stephen Bowie, a film and TV historian with the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, writes on his blog that Tragedy in a Temporary Town had a clear link to McCarthyism and showed “sly cynicism” and “political courage.” About the main character, played by Lloyd Bridges, Bowie wrote: “Begg’s ineffectual liberalism and hypocrisy point a finger at various players on different sides of the blacklist, and the provocative casting of Lloyd Bridges (a House of Un-American Activities Committee friendly witness) must have resonated with Lumet…”

In 1953, at the height of the McCarthy era, came news that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were accused of conspiring to pass atomic bomb secrets to the Soviets. They maintained their innocence. Their lawyers argued they were victims of communist hysteria. They were convicted and became the first and only American citizens to be executed for espionage during peacetime.

Lumet remembered it as “chilling” and, years later, collaborated with E.L. Doctorow adapting his epic novel based on the Rosenbergs, The Book of Daniel, to screen. Daniel premiered in 1983 and took a critical hit because the public mistook it for a factual account of the Rosenberg story when it was actually a more nuanced examination of the role of the radical. They made a joint statement upon the release of the film: “Through Daniel’s search for self-discovery in his own memories, as well as his contacts with people who were involved in his parents’ case, we see from the inside three decades in the life of American dissent—from the Depression and World War II to the McCarthy period and the anti-war movement of the 1960s. The effects of parents on children, of ideologies on life, of history on individuals, are questions considered in the story of two generations of a family whose ruling passion is not success or money or love, but social justice.”

The critical failure of Daniel led Lumet to try again with Running on Empty, a similarly themed family drama this time written by Naomi Foner Gyllenhal. Running on Empty featured River Phoenix as a teenager coming of age while living on the run with his fugitive parents, two idealistic radicals from the 1960s who are aware their children are paying for their passion. Frank Cunningham writes in Sidney Lumet: Film and Literary Vision, “Having learned to abandon violence, they have not abandoned their social and political ideals, and stand with Lumet’s memorable rebels and outsiders, from The Fugitive Kind through Daniel and Night Falls on Manhattan in the director’s continuing cinema of conscience.”

Jurisprudence and Justice

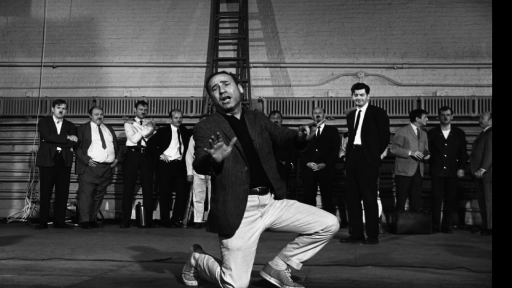

12 ANGRY MEN, (aka TWELVE ANGRY MEN), director Sidney Lumet (hat), on set, 1957

”I’ve never been aware of it as wanting to do movies about the criminal justice system, and then I look back and there are seven, eight, nine of them involved with it,” he said. ”I guess when you’re a Depression baby, someone with a typical Lower East Side poor Jewish upbringing, you automatically get involved in social issues. And as soon as you’re involved in social issues you’re involved in the justice system.” Sidney Lumet to The New York Times critic David Margolick

In 1956, Reginald Rose and Henry Fonda commissioned Lumet to turn Rose’s stage production of 12 Angry Men into a Hollywood movie. This began to define Lumet as one of the industry’s most socially conscious directors. Themes of justice, personal integrity, and radicalism would later appear in the scripts he chose, the characters he brought to life, and the writers he chose to work with, including Rose, who was considered the conscience of television.

The film 12 Angry Men cost $349,000 to make and premiered in Los Angeles on April 10, 1957 to wide critical acclaim. A few days later it opened with great anticipation in New York, followed by a special screening at the United States Capital and eventually a spread in Life magazine.

In the film Fonda plays Juror 8, who casts the lone ‘not guilty’ vote as he and his fellow jurors deliberate the fate of a young Puerto Rican boy facing the death penalty for his father’s murder. A metaphorical counterargument to the witch hunts of McCarthyism, it is also another quest for social justice, this

time by way of the American jury system, which Alexis de Tocqueville believed was a cornerstone of American democracy and made for better citizens.

“The movie 12 Angry Men starts by showing lay participation at its worst,” writes Cornell Law Professor Valerie Hans, an expert on the American jury system, in her paper, Deliberation and Dissent: 12 Angry Men Versus the Empirical Reality of Juries. “The discussion is cursory,” says Hans. “The jurors exchange insults and putdowns. The comments about the trial and the defendant reflect snap judgment and prejudice. In short the men are really bad jurors. But the deliberation transforms the men into thoughtful jurists who consider the evidence more deeply and reason through it to their collective verdict.”

Critic Roger Ebert called it “a masterpiece of stylized realism.” Even New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, who would often criticize Lumet for lacking a cohesive style, said in her review that it was, “so sure-fire it has the crackle of a hit.” More than 50 years after its premiere, the film is analyzed by critics and discussed in university classrooms—from law to humanities—to generate discourse on justice, gender, race, group dynamics, leadership, and American jurisprudence. Two Supreme Court justices have cited 12 Angry Men among their favorites: Justice Steven Breyer said in 2005, “The longer I’ve been a judge the more I like it…you feel, ‘my goodness, he got it, the power of the jury.’” Justice Sonia M. Sotomayor has credited it with inspiring her career in law. “It sold me that I was on the right path, “she said. “This movie continued to ring the chords within me.”

The film directly addresses American jurisprudence but also examines the philosophical and ethical questions surrounding ideas of justice, fairness, personal integrity, compassion, and honor. It raises questions about the law itself and examines how members of society treat each other within that context. The quintessence of a Lumet film is a character who questions morality, questions society, even if there is no easy answer. The film 12 Angry Men never reveals the defendant’s guilt or innocence, because it’s not intrinsically important. “I don’t really know what the truth is. I don’t suppose anybody will ever really know,” says Juror 8 to the group. “Nine of us now seem to feel that the defendant is innocent, but we’re just gambling on probabilities—we may be wrong. We may be trying to let a guilty man go free.”

Questioning Authority, Taking the Moral Path

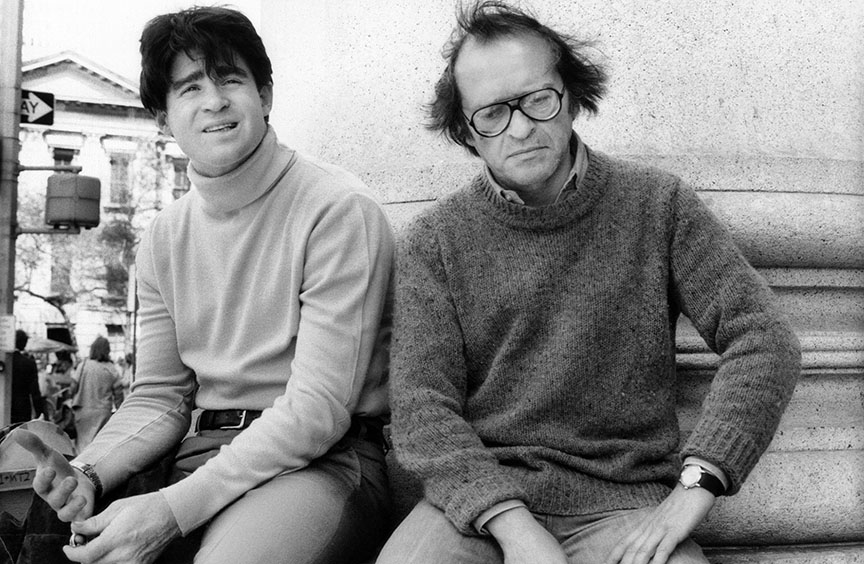

Serpico (1973)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Shown from left in foreground: Al Pacino, director Sidney Lumet

In 1995 Professor Terry Diggs’ interviewed Sidney Lumet during a seminar on Film and the Law at the University of California and asked what drew him to films about jurisprudence. “It seems as if you always come back to the subject of law, whether you’re dealing with an outlaw, a lawyer, or a police officer. Why do you find this metaphor, of law, to be such an expressive one?” Lumet answered, “Let’s start with a very simple statement: If the law doesn’t work, nothing can work in a democracy. It’s the basis of everything.” He went on to say, “There’s your instinct and there’s your life experience. I grew up very poor in the roughest sections of New York and you simply become very interested in justice because you see an awful lot of injustice around.”

Lumet’s film career took off in the 1960s as a new generation of Americans were beginning to protest current injustices—namely civil rights and the Vietnam War—and as Hollywood was on the brink of a renaissance from which emerged some of American cinema’s finest films. By mid 1960s studios were seeing big returns on Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music but were, nevertheless, aware they had lost touch with America’s radically changing culture. A new generation of directors who did have their finger on the cultural pulse stepped up to re-shape the landscape of American cinema. This heyday for directors was further enhanced by the influence of the French auteur theory that put high value on consistent and individualized style and was embraced by notable critics like Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice.

“Lumet threw a wrench in the whole notion of the auteur theory because he ignored it,” said Bryn Mawr Professor Andrew Douglas in an interview. Douglas uses Lumet’s work in his film classes and created a course called “Dogged Defiance: Sidney Lumet.” He says Lumet’s filmmaking defied classification because it changed with every story he told. Instead, Lumet focused his artistic expression on “telling stories of counterculture figures questioning authority, which was en vogue at the time.” The result was a string of hits that evinced the energy and consciousness of the moment, including the triumvirate of Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network.

Lumet’s films during this time knocked hard on the door of justice, exploring abuses of power and radical stands against corrupt institutions. He shot almost every one of them in his hometown of New York City, which he felt provided a more realistic gritty urban palate for his stories. The city began to appear so often in his films it was almost considered another of his characters.

Serpico (1973) was a police thriller featuring another acclaimed performance by Al Pacino, this time in the role of an isolated and intense undercover cop whose radical idealism defines his search for justice as he blows the whistle on payoffs and corruption in the police department. Based on a true story (the book written by Peter Maas; screenplay co-written by former blacklisted writer Waldo Salt) the movie showed Lumet at his best, filming on New York City streets with a talented crew of actors playing characters in moral conflict and a story that was in perfect sync with the mood of the country.

The radical searching for social justice, often alone against an institution, is the common trait among Lumet’s characters, says Andrew Douglas, who calls Serpico, “smart storytelling, smart filmmaking and smart character development.” He adds, “If we went down a list of Lumet’s characters…we would see that even the characters of Diana Ross (The Wiz) and Henry Fonda are similar in that they have hostile enemies, are trying to achieve the impossible and convince others of their way of thinking, and up against an institution they don’t know how to navigate.”

“I love characters who are rebels, because not accepting the status-quo, not accepting the way it has always been done, accepting this is the way it has to be, is the fundamental area of human progress, and drama,” Lumet said. “Clearly I am not denying for a minute that I am attracted to the radical, that I am attracted to the questioner… I do not know if life is possible without them… one of the staples of drama, is question authority.”

In 1976 The Six Million Dollar Man was one of the most watched shows on TV, Your Erroneous Zones topped book charts and Afternoon Delight was a top selling single. The memory of Watergate was still fresh for Americans and the government remained locked in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. The American people, in spite of a recent recession, seemed over the radicalism of the 30s and 60s and were now absorbed in what Tom Wolfe declared the “Me” decade. “The word proletarian can no longer be used in this country with a straight face,” Wolfe wrote in the August 23, 1976 issue of New York. “So now one says lower middle class.”

Less than two weeks after Jimmy Carter unseated Gerald Ford to win the presidency, Lumet and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, premiered their film Network, a tale of power run amuck in the corporate world of network television where both men had spent their early careers. Network was a landmark film that garnered immediate respect for its portrayal of greed. The following spring it was honored with ten Academy Award® nominations, including Chayefsky for best screenplay and Lumet for best director. As of January 14, 2015 it is still the only film to receive five acting nominations: Faye Dunaway, Beatrice Straight, William Holden, Ned Beatty, and Peter Finch.

The film was set in New York in the world of network news where ratings and shares determine an anchor’s worth. When longtime anchor Howard Beale, played by Finch, is fired for low ratings, he announces on air that he will “blow his brains out” on the following week’s show. Network executives gleefully take advantage of the unexpected boost in their numbers. The film was called a satire, but Lumet said it was “sheer reportage.” Chayefsky’s prescient script about the power of corporate America, for which he won an Academy Award®, was even referenced during recent social unrest: “A literate, darkly funny and breathtakingly prescient material that prompts many to claim it as the greatest screenplay of the 20th Century,” wrote actor Rob Lowe in The New York Times in 2014.

One of the most referenced scenes is Beale’s unhinged on-air call to action:

“I want you to get MAD! I don’t want you to protest. I don’t want you to riot. I don’t want you to write to your congressman, because I wouldn’t know what to tell you to write. I don’t know what to do about the depression and the inflation and the Russians and the crime in the street. All I know is that first you’ve got to get mad. You’ve got to say: ‘I’m a human being, god-dammit! My life has value! So, I want you to get up now. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs. I want you to get up right now and go to the window. Open it, and stick your head out, and yell: ‘I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this anymore!”

In addition to Chayefsky’s Oscar®, Faye Dunaway, Beatrice Straight, and Peter Finch, who died shortly after the film premiered, also received awards. Writer David Itzkoff described the film’s impact in his 2014 book, Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in the Movies: “…by arriving at a moment of maximal national frustration, the movie made itself the center of an argument about society and personal identity and inserted itself into the cultural lexicon…”

The courageous characters of Lumet’s 70s-era films displayed a tangible, almost explosive, challenge to injustice. In the 1980s Lumet continued his examination of the radical, but now, rather than group protest or solidarity against an oppressive authority, we began to see noble often self-defeating loners standing up against corrupt systems.

VERDICT, Charlotte Rampling, Paul Newman, Sidney Lumet, 1982, directing the actors

His 1982 film The Verdict featured a screenplay by David Mamet (who referred to Lumet as “the maestro”), with Paul Newman as Frank Galvin, a worn-out negligence lawyer with whiskey on his breath and a client roster culled from funerals. The possibility for personal redemption comes when a routine malpractice case turns into a chance to stand up to societal greed and defend the rights of a comatose woman. “Its courtroom setting harkens back to 12 Angry Men, Lumet’s first picture, and the character played by Newman (brilliantly, it must be said), wrapped in a blanket of furious, self-ordained solitude, recalls similar little-guy-against-the- system characters in Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Prince of the City,” wrote critic and author Don Shewey in a 1982 article in Film Comment.

The Verdict was nominated for five Academy Awards®, including best director, actor, and screenplay, and is noted for Galvin’s moving jury summation towards the end of the film, in which he speaks of justice as if its real meaning is coming to him at that very moment; a surrendered summation of his own life not just trial evidence.

“You know, so much of the time we’re just lost. We say, ‘Please, God, tell us what is right; tell us what is true.’ And there is no justice: the rich win, the poor are powerless. We become tired of hearing people lie. And after a time, we become dead… if we are to have faith in justice, we need only to believe in ourselves. And act with justice. See, I believe there is justice in our hearts.”

The urban police drama Prince of the City, based on a true story, premiered in 1981 with Treat Williams as Daniel Ciello, a New York City undercover narcotics officer who makes so much money from bribes that he and his fellow officers are deep into profiteering. Ciello’s moral dilemma begins when he’s asked to assist in an internal investigation against corruption and to inform on his friends. “The plight of the informer in Prince of the City, (Lumet) admits, directly reflects his memories of the panic and moral ambivalence of the McCarthy era,” wrote Shewey in The Reluctant Auteur. In our film Lumet says, “I did not know how I felt about Daniel until I saw the first cut and I ran it…and I said ‘Oh, I made him a hero.’ I had no intention of doing that; everything was questions, questions, questions, questions. Consciously I had no feeling of hero, villain, what-have-you… I think that element of not knowing can lead to some wonderful work.”

Conclusion

Lumet’s use of ambiguous characters and his non-judgmental gaze are fundamental to the philosophical query: What is moral? There is no definitive answer. But the asking of the question, as Lumet does with each character in his films, reveals a piece of their humanity. Morality is an abstract concept without people; it becomes reality when people question justice, fairness, corruption, religion, courage, and duty. For Lumet it was all about the characters, how they made decisions and what mattered to them. An examination of Lumet’s films takes you straight to his characters: Juror 8, Daniel Ciello, Frank Serpico, and Howard Beale.

“Even if he believed—and he did—that art ultimately does not have the power to change anything, his art, reflective of his conscience and craftsmanship, had something to say about human life in a system that too often is rigged against a smooth sail. It is this emphasis on human life that is at the heart of his humanity,” said Joanna Rapf in her correspondence with the filmmakers.

Pursuing reality through cinematic stories is what Sidney Lumet spent his life doing. “It’s not a privilege, it’s your work,” he says in our interview. “My job is to just do it. And I’m delighted if it has a manifestation for you larger than its manifestation for me. That thrills me. That just means I did it well.”

“For him, it was a matter of empathy, but it was also a matter of the cathartic theater of movies. The more he could show you a character who had fallen from grace, and the more he could make you see you had something in common with that character, the more he could produce an almost physical feeling, a shudder of recognition. For Sidney Lumet, that was grace.”

– Critic Owen Gleiberman, upon Lumet’s death in April 2011