Black actresses have always faced barriers.

Initially, they were not allowed to be on screen at all. Then, they could only play certain types of roles: typically either as a servant and/or enslaved woman, or as an “exotic” temptress. Never a character that was fully realized, one with depth or nuance.

While we would like to think that things have changed significantly, the facts don’t bear that out. Indeed, even after Black actresses win some of the most coveted awards in the entertainment industry, they still struggle to find meaningful work. Halle Berry, Whoopi Goldberg and Mo’Nique have all publicly discussed this phenomenon as Oscar winners. Berry explains in How It Feels To Be Free that while she expected doors would open for her as the first Black woman to win an Oscar for best actress, she found the opposite to be the case. In fact, Oscar winner Octavia Spencer recounted that she received assistance from Jessica Chastain in negotiating a salary five times larger than it otherwise would have been, because Chastain tied Spencer’s salary to her own. In other words, Jessica Chastain, a white woman, used her privilege to advocate on behalf of Octavia Spencer, the Oscar winner.

The small screen is not much kinder to Black actresses.

Their roles are often not fully realized individuals, but merely the sassy friend of a white character. Diahann Carroll starring in “Julia” from 1968 to 1971 was a significant shift in the zeitgeist. As she discusses in How it Feels to Be Free, this is the first time that we see a Black woman in the lead role of a television show with a non-stereotypical role. Nevertheless, while Carroll won the Golden Globe for her role, it would be more than 15 years before she appeared on another TV series.

Black actresses also face issues on TV and film sets that their white counterparts do not. Hair and makeup are frequently a challenge. Stylists are not often skilled in how to style Black hair, and may not have the correct makeup palettes for darker skin, as Diahann Carroll discusses in How it Feels to Be Free. This results in many Black actresses having to come to set “camera ready,” spending their own time and resources to achieve the look a director wants while sitting in a salon or at their bathroom mirrors.

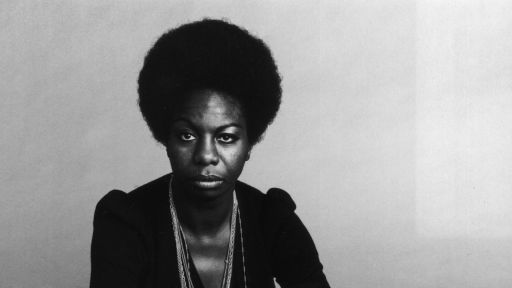

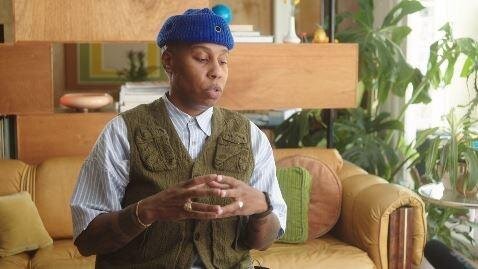

Hair is a particularly controversial subject. One would think that styling the hair that grows out of our heads would be the easiest thing to do. But as we see in How It Feels To Be Free Black women were often not allowed to wear afros on set, even though that was one of the most popular styles in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, it was a revolutionary act when Cicely Tyson wore a short afro on screen, later transitioning into an intricate braiding style. As Lena Waithe said, “Her deciding to wear her hair in its natural state was almost a form of protest.” It is poignant that Mother Cicely has transitioned from this earthly realm and become one of our most revered ancestors. But she left many gems of wisdom behind. Most importantly, she encouraged us to be intentional about our choices in work and to use the platform we have to speak our truth, even through our hair.

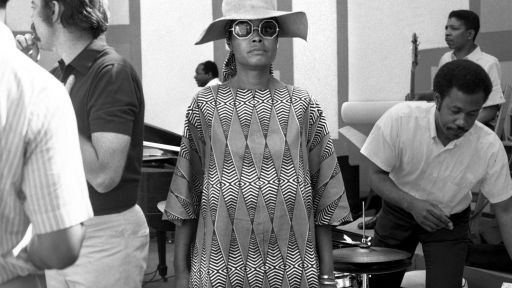

NEW YORK – CIRCA 1967: Jazz singer and actress Abbey Lincoln poses for a portrait circa 1967 in New York City, New York. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Today, Black women are still facing discrimination with respect to their hair, both inside the entertainment industry and out. Many Black actresses choose to wear a wig or weave, styles that protect their natural hair. This is often because a wig might more closely resemble the hair of white women, with which a stylist may have more experience, but also because it protects the actress’ hair from becoming over processed or damaged by someone unskilled. Further, a straight hair weave might more closely resemble the look a director prefers, a preference that is rooted in eurocentric standards of beauty and white supremacy.

Outside of the entertainment industry, Black girls and women fare no better.

Around the country, Black girls have been sent home from school because of their hair. In 1999, Venus Williams was penalized during the Australian Open when some of the beads from her signature cornrow style fell out during a match. Until 2017, Black women in the military were forbidden to wear their hair in locs, a hairstyle that is one of the most natural to Black women.

To combat this discrimination, the CROWN Act was created in 2019. The CROWN Act, which stands for “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair,” is a law that prohibits race-based hair discrimination, which is the denial of employment and educational opportunities because of hair texture or protective hairstyles including braids, locs, twists or bantu knots. To date, the CROWN Act is now law in seven states across the country. It is telling that the issue of hair discrimination has become so rampant that laws are necessary to combat it.

How It Feels To Be Free gave me a sense of pride in watching stalwarts of the entertainment industry break barrier after barrier as Black women. But it also left me longing for what could have been. A world that celebrated Abbey Lincoln as she spoke forcefully about civil rights, instead of shunning her. An industry that did not insist on sexualizing Pam Grier and instead provided her roles in which she could be an action star without the revealing costume choices. A studio that did not relegate Lena Horne to mere singing roles, despite her talent as an actress.

Some strides have been made, but quantity of appearances on the big and small screens does not always translate to quality of roles. We often see the most significant advancement when stories centering Black women are told by Black people as directors, writers and producers; there is an unmistakable cultural context. In other words, representation matters, both in front of and behind the camera.

While there are a few exceptions, Black actresses are still longing to know how it feels to be free.