Rissi Palmer, independent country music artist, songwriter, storyteller, entrepreneur and mother, is a Grammy-nominated performer who has worked at her craft since she was 17 years old, and left college in her freshman year to come to Nashville to make a living making music. Under the loving watch of three generations of mothers, Palmer grew up listening to and loving country music women like Dolly Parton and Patsy Cline, as well as gospel, soul, hip-hop and blues. She has made music in all of these genres, but country music is where she’s made her home, despite the gatekeeping of an industry that often made her feel like she was running in place. After landing a recording contract with a label in Nashville, Palmer experienced tight control and surveillance, from the kinds of stories she could tell in her lyrics to how she should wear her hair.

This feeling of running in place was one that many Black women artists navigating country music have experienced, historically. From Linda Martell, Palmer’s biggest inspiration, to Dona Mason, the Black country artist who had been the last Black woman to chart a country hit 20 years before Palmer, Black women have fought to find a place in an industry that is only recently beginning to shift.

Black women have deep roots in country music, and are among the originators of the genre.

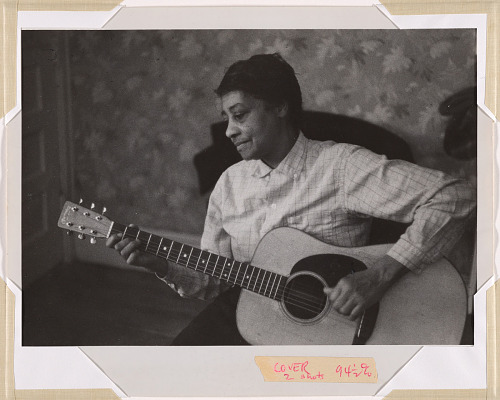

The banjo is, after all, an instrument with African origins, cousin to the current West African instrument, the akonting. Black people are said to have brought their banjos (and the knowledge of how to make them), with them during the Middle Passage. The first string band performers were enslaved people, and this music was appropriated to form Blackface minstrelsy, the United States’ first successful commercial music. A major country music guitar and banjo picking style originated in the Piedmont region’s blues, exemplified by virtuoso Black woman musicians Elizabeth Cotten and Etta Baker.

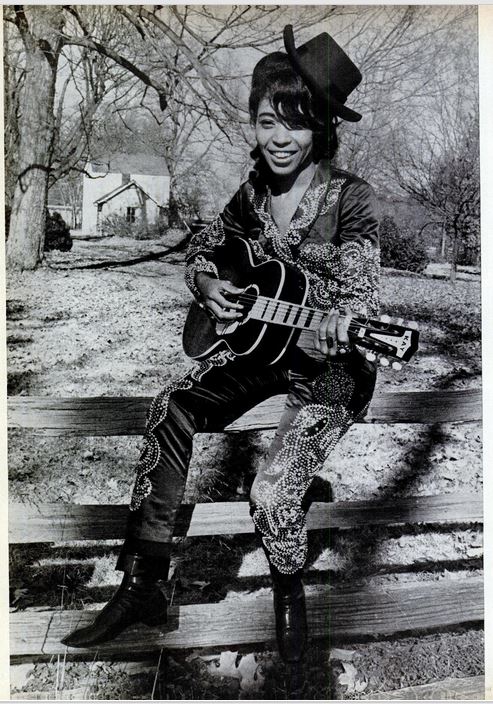

Elizabeth Cotten. Photo by John Cohen, courtesy Deborah Bell, New York/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Some of the erasure of this history of origins can be explained by the ways that from the 1920s on in the record industry, recorded music was segregated into “Hillbilly” records (which was eventually called country and western, or just country music, and was marketed specifically to white audiences), while “Race” music (including blues), was marketed as “Black” music. But both performers and fans crossed these racial lines, despite the rules, and despite the idea that this segregation was “natural” and grounded in the body. In this way, country music, like other American musical genres have reflected the informal, but sometimes deadly laws of Jim Crow. The segregation of country music continues today, upheld by many of the ways that country music is sold, marketed, distributed and written about, with very few exceptions.

For a time, one of those exceptions was Linda Martell, a Black country music artist who was the first Black woman to perform on the Grand Ole Opry’s stage.

Three songs from her 1969 album “Color Me Country” were hits on Billboard’s country charts, including “Color Him Father,” “Bad Case of the Blues” and “Before the Last Teardrop Falls.” Yet soon after its release, and a limited run of public appearances, her album label, Plantation Records, released her from her contract. Martell has since shared stories of racist insults and threats of violence by country music audiences and by television executives, and an almost daily wearing down of her spirit. “Color Me Country” was her only country music album, though she’s continued to make music professionally and semi-professionally.

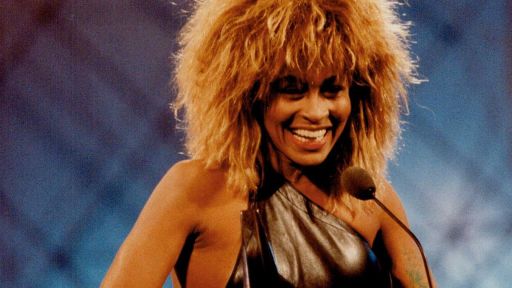

Tina Turner, whose hit “Nutbush City Limits,” chronicled her upbringing in the small town of Nutbush, Tennessee, chose to make her first solo album a country album, “Tina Turns the Country On!” in 1974. This album, made up of covers by country songs by Kris Kristofferson and Dolly Parton, was nominated for a Grammy the following year, but until recently the album was little known except by a small circle of fans, and is still out of print.

Other Black women artists in soul and R&B who have recorded country music include Millie Jackson (on her album “Lil Bit Country”), Anita Pointer (with her hit “Too Many Times”) and The Pointer Sisters (who performed their country hit “Fairytale” on the Grand Ole Opry Stage in 1974 , to a mixed audience response). When in 1987, Dona Mason charted a country hit with her cover of “Green Eyes (Crying Blue),” sung with Danny Davis, she was the last Black woman to appear on Billboard’s country music charts before Rissi Palmer broke her record with her 2007 song, “Country Girl.”

After the initial promise of “Country Girl,” Palmer decided to leave her label and had to fight in the courts to be released from her contract. But that experience taught her the value of her own contributions to the genre as an independent artist. Working independently gives her the place to tell the kinds of musical stories that reflect a full spectrum of Black women’s experiences. As Palmer tells The 19th News’ Jennifer Gerson:

“I think some of the best storytellers, and authors, and thinkers and poets are Black women — and we are as entitled to have our stories told as anyone else. And country music is a place where Black women can tell their stories.”

Along with her own songs, as host of the Apple Music radio show that she created, “Color Me Country,” named after Martell’s album, Palmer brings to the airwaves old and new Black, Latinx and Indigenous country music artists that “for too long have been kept out of the spotlight,” as the show’s opening puts it. Palmer has also created the Color Me Country Fund for emerging BIPOC artists. Color Me Country Radio has become a place for Black, Brown and Indigenous musicians, journalists, critics and producers to discuss the struggles of the country music industry.

Her guests have included Black women country artists Chapel Hart, Miko Marks, Mickey Guyton, Brittany Spencer, Yola, Rhiannon Giddens, Allison Russell, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, Queen Esther, Yola, Madeline Edwards, Lilli Lewis, DeLila Black, Joy Oladokun, D’orjay the Singing Shaman and Reina Robert, among others. One episode features Black queer country fan and activist Holly G., who has created The Black Opry Revue, a collective of Black Country Music artists that tour the country. “Color Me Country” has discussed country music’s roots in the blues, Black cowboys and hip-hop. But the show is also deeply personal. One recent Mother’s Day episode featured Palmer’s young daughters Grace (12) and Nova (4) as guests.

Rissi Palmer’s most recent tour, together with 20 year Black Country Music veteran Miko Marks, is titled “Still Here.” When they sing the title song together, we hear that struggle beneath that boast, as well as the joy of being able to claim it together. What seems to have sustained them is the knowledge of the Black women before them who have fought to claim country music.