Inspired: People with Disabilities Breaking Barriers

There are 56 million Americans with disabilities alive today, representing approximately one in four people. Disability culture and activism has existed from ancient times to present, but we rarely hear about people with disabilities, who are often seen as victims. Disability culture is the celebration of the uniqueness of disability; it is about visibility, pride, and changing societal perceptions of value and contribution. It isn’t about people with disabilities being included in society but people with disabilities driving and transforming society.

Inspired is a series of essays that tells the story of people with disabilities: renegades, rebels and revolutionaries who changed the world and whose stories should be told.

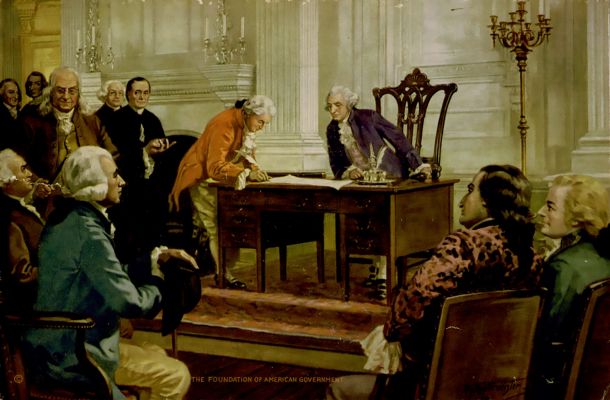

Gouverneur Morris – Playboy and penman of the American Constitution

There is no one better to begin this series with than Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816), who was pivotal in the writing of the United States Constitution and its famous Preamble, changing how Americans think of themselves.

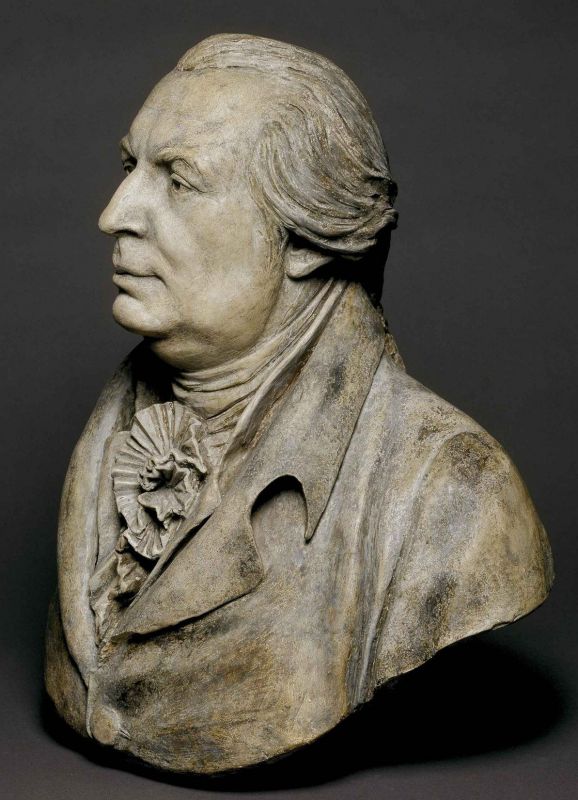

Portrait of Gouverneur Morris by Ezra Ames. Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

The history books typically refer to the Founding Fathers of the United States with pomp and reverence. Paintings and images of the era often show staid men in white wigs who seem to have lived stuffy lives. None of that applies to Gouverneur Morris. This Founding Father was an unrepentant rebel, rogue, diplomat and consummate ladies’ man.

At 6-foot-4, Morris was handsome and witty. He was fond of the ladies, and married or not, they were equally fond of him. In addition to romancing a bevy of women of New York high society and even more in Philadelphia, Morris’ lovers would also include an Italian noblewoman from Milan, the wife of a banker and diplomat in Leipzig, a Prussian King’s mistress, his landlord’s daughter in Denmark, and the wife of the Keeper of the Gardens in the Louvre (and also mistress to the heir to the French throne).

Morris’ left leg was amputated when he was a young man. The official story was that it had been crushed in a carriage accident. However, rumors abounded that it was actually injured when he leapt from a second story balcony to avoid a jealous husband who caught him in bed with his wife. Losing his leg didn’t slow Morris’ romantic adventures down at all. In fact, his friend John Jay even wrote that he wished Morris “had lost something else.”

Morris was born to a wealthy family in 1752 in what would be known today as the Bronx in New York. Even from his early years, he was charming, clever, irreverent and never afraid to say what he really thought – a trait that would get him into and out of trouble his entire life.

He was accepted to Kings College (now Columbia University) at only twelve years old, after which he went on to study law. At twenty four, he became the youngest member of the New York Provincial Congress. It was only a year later that the battles at Lexington and Concord signaled the start of the American Revolution – “the shot heard ‘round the world.” Morris embraced the idea of independence from Great Britain.

His aristocratic family did not approve. His mother was a staunch supporter of the British and his brother an officer in the British Army. In fact, Morris found himself turned out of his own home when his mother donated their house to the British army to use for military purposes. He moved to Pennsylvania and wouldn’t see his mother again for seven years.

Morris was a strong supporter of George Washington. The two were friends from the first time they met at Valley Forge in 1778, a pivotal point in the war. Morris, upon seeing the suffering of the soldiers of the continental army, the “army of skeletons . . . naked, starved, sick, discouraged,” committed to supporting Washington’s troops with funds and supplies so they could continue the battle for independence. The two men would remain good friends for the rest of their lives.

Gouverneur Morris portrait bust by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1789, Paris. Morris would go on to become America’s second minister to France. He left one revolution and found himself right in the middle of another. He served during the bloodiest days of the French Revolution. Morris was eventually thrown out of France when it was discovered he was part of a plot to rescue Marie Antoinette from the guillotine.

After the war, along with George Washington, Morris would attend the Constitutional Convention. Representatives of the original thirteen states were invited to discuss, debate and decide how they would be governed. Morris was very outspoken and forceful about his opinions, especially on slavery. He believed slavery was a “nefarious institution,” and “the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.” Over the three months of the convention, a fiery Morris gave 173 speeches, more than any other attendee. This is especially impressive when you consider that he was away on family business for one of those months.

Morris was assigned the job of writing out the final language of what would become the United States Constitution. He completed the work in three days. However, he didn’t just write down what had been agreed upon; he actually made several sly changes, the most impactful being to the Preamble.

The original language in the Constitution draft said: “We the People of the States of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia – do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.” It’s a document about how states will govern themselves.

Morris changed it to: “We, the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, to establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

At the time, most colonists still thought of themselves as citizens of individual states. Morris’ alteration changed it from a document about a confederation of states working together to states coming together as a new, unified nation – America.