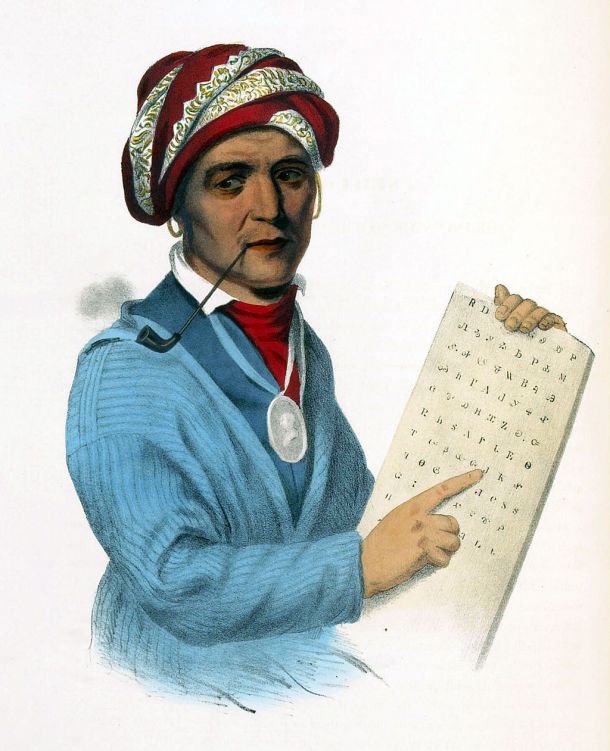

A lithograph from History of the Indian Tribes of North America. This lithograph is from the portrait painted by Charles Bird King in 1828.

Inspired: People with Disabilities Breaking Barriers

There are 56 million Americans with disabilities alive today, representing approximately one in four people. Disability culture and activism has existed from ancient times to present, but we rarely hear about people with disabilities, who are often seen as victims. Disability culture is the celebration of the uniqueness of disability; it is about visibility, pride, and changing societal perceptions of value and contribution. It isn’t about people with disabilities being included in society but people with disabilities driving and transforming society.

Inspired is a series of essays that tells the story of people with disabilities: renegades, rebels and revolutionaries who changed the world and whose stories should be told.

Sequoyah: The inventor of Cherokee writing

His Cherokee name was Sogwali, or Sikwâ’y, but most of the world knows him as Sequoyah. In the 1800s, Sequoyah recognized the value of the European settlers’ “talking leaves,” and set out to create a written language for the Cherokee.

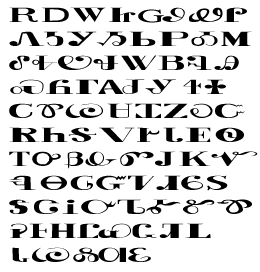

An alphabet uses individual symbols for consonants and vowels. Sequoyah’s writing system was directly connected to spoken Cherokee. Its 86 symbols represented consonant and vowel combinations – syllables. This is why written Cherokee, or Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, is correctly called a syllabary, not an alphabet. His syllabary transformed not only the Cherokee Nation, but had far-reaching impacts beyond North America.

Sequoyah was born in a small town just a few miles from Echota, the old capital of the Cherokee Nation in what is today eastern Tennessee. His mother was of the Red Paint Clan. His father has been described as a white man; some sources say he was a German immigrant, and others claim that he was an officer in George Washington’s army. However, he played no role in Sequoyah’s life. Sequoyah was left to be raised by his mother alone in the traditions of the Cherokee. He would grow up to become a trader and later a successful blacksmith and silversmith. He was self-taught, creating his own forge and tools.

While almost all accounts of Sequoyah mention a significant limp, there is much disagreement as to the reason for his disability. He may have been born with it. One historical account specifically described his “lame and shrunken leg;” another, from the “Cherokee Phoenix” newspaper, reports that, “he was the victim of hydro arthritic trouble of the knee joint…and this affliction caused a lameness that characterized him during life.” Others mention the possibility of a hunting accident when he was young. But regardless of the cause, Sequoyah was a person with a disability.

The story of how Sequoyah came to the idea of creating a written script for Cherokee is another mystery with several potential answers. One version was that he overheard a conversation among Cherokee youth debating how white men communicated through writing. While the young Cherokees ascribed the “talking leaves” to sorcery or witchcraft, Sequoyah believed that it was an invention and right then declared that he could easily create such a system himself.

Another possibility is that when Sequoyah served in the Cherokee Regiment during the War of 1812, he witnessed the power and usefulness of writing for things such as recording events and troop activities, relaying messages to units in other areas, and even simply sending letters home to friends and family.

Regardless of the reason, Sequoyah determined that a system for writing was critical for his people. He would spend the next ten years of his life experimenting with ways to capture the Cherokee language. He started using pictographs with an image or graphic for each word but realized very quickly that it was too unwieldy. When that didn’t work, he moved to a phonetic system, matching symbols to spoken Cherokee, breaking up each word into its basic sounds. His desire to create a language for his people became all-consuming. In fact, several sources talk about how his wife, Sally Waters, burned his work.

“He [Sequoyah] was laughed at by all who knew him, and was earnestly besought by every member of his own family to abandon a project which was occupying and diverting so much of his time from the important and essential duties which he owed his family.”– Chronicles of Oklahoma; Volume 11, No. 1; “Captain John Stuart’s sketch of the Indians.”

By this point in time, Sequoyah and many of the Cherokee had been dispossessed of their lands around Echota, and he was now living in Willstown, Alabama. It was there that Sequoyah finally succeeded in designing a new writing system with 86 symbols to represent the various syllables. Written Cherokee would be the very first written syllabic form of a Native American language. What makes this such an impressive feat is that Sequoyah did not read or write at all. He created a written language from scratch.

In 1821, he was ready to publicly reveal Cherokee writing for the first time. Sequoyah summoned friends, neighbors and community leaders to explain his invention. They didn’t believe him; some even accused him of witchcraft. So, with the help of his six-year-old daughter, Ahyoka, he set up a demonstration. Sequoyah sent her out of the room and asked one of the men present to say a word. He wrote it down and then called Ahyoka back into the room to read the word aloud. They were astonished. Sequoyah’s discovery would go on to have a phenomenal impact.

Sequoyah’s syllabary in the order that he originally arranged the characters. Because of decades of government policies hostile to Native Americans, Cherokee is now an endangered language. Less than 5% of Cherokee today are fluent in Tsalagi. However, there are efforts to preserve the language and because of Sequoyah’s invention, there is a significant amount of documentation of the language that has helped to reconstruct and safeguard Tsalagi for future generations.

The tribal leaders recognized the value of Sequoyah’s writing system. Within six months, more than 25% of the Cherokee Nation had learned how to read and write. In less than three years, the Cherokee were three times more literate in Tsalagi than their white neighbors were in English.

Pressure from the federal government had already forced many Cherokee from their homelands, splitting the Cherokee Nation between east and west. Sequoyah had created a tool to keep its members “united and informed.” But it wouldn’t be enough. Seeing the rising tensions between white settlers and his people in the East, which would culminate in the infamous Trail of Tears, Sequoyah moved to Oklahoma in 1829.

Throughout his life, Sequoyah remained faithful to the traditions of the Cherokee people, never adopting white dress, religion or other customs. He spoke Cherokee exclusively, though many scholars now suspect he did have some knowledge of English. But his focus was always the benefit and elevation of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1839, Sequoyah worked to help Cherokees flee from Texas where they were being killed indiscriminately. Two years later, he set out to find a lost band of Cherokee believed to have wandered far to the south and west, and reunite them with the rest of the Cherokee Nation. Sadly, Sequoyah would not return from this journey, succumbing to illness in August 1843.

Sequoyah’s impact and influence have no parallel in history. His syllabary spread beyond the Cherokee, leading to the creation of syllabaries for many other groups, including the Cree syllabary used by the largest group of First Nations people in Canada, Liberian syllabaries (Vai and Bassa) in West Africa and another in China. Over all, Sequoyah’s work influenced the creation of 21 scripts for more than 65 languages.