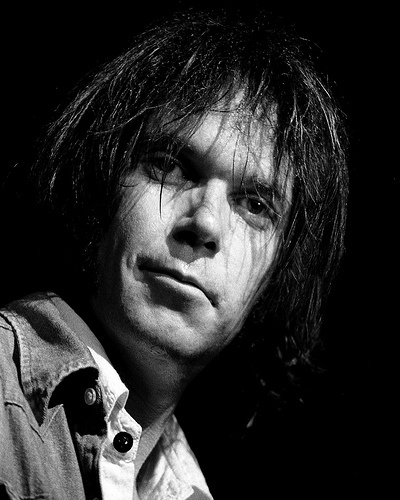

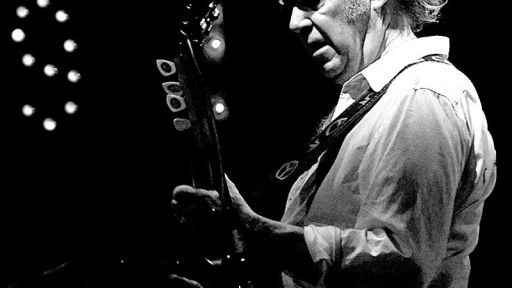

There’s a short bit of film from 1970, famous among hardcore Neil Young fans, in which the then-25-year-old musician visits an L.A. record store only to find a Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (CSNY) bootleg album for sale. Bootlegs, of course, were those unauthorized LPs (and later CDs) featuring live performances by your favorite rock star, usually originating from a concert tape poorly recorded by an audience member. Neil Young bootlegs were prevalent and popular in underground record stores, apparently much to the artist’s displeasure. In the old footage, Young simply claims the record as his property as the perplexed store clerk phones for help.

You’d be right if you said all he was doing was disrupting a supply chain in which not only was an inferior version of his work being sold, but he wasn’t even getting paid a royalty! It turns out, however, that there was much, much more going on.

Before we get to that, it should be noted that in the ‘70s Neil Young was at one of his several artistic peaks: his output included After The Goldrush, Harvest, Tonight’s The Night, and Rust Never Sleeps, which still regularly wind up on critics’ best-of lists. In a decade when some big-time rock artists might take years to record a single album, Young released no fewer than 10 of his own, plus two with CSNY and another with The Stills-Young Band, not to mention a film soundtrack and a triple-disc career retrospective.

But even at the time, Young’s live shows proved that that was only a fraction of what he was producing. Case in point: when Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young went out on their massive reunion tour in 1974, Stephen Stills debuted five previously unreleased songs, David Crosby and Graham Nash just two each. Neil Young debuted 18, five of which weren’t released for 40 years. But now, thanks to a career’s worth of careful collecting on Young’s part, we can experience what his most loyal fans of the era never could, all at the Neil Young Archives.

Young saved just about everything: multitudes of recorded concerts, many albums’ worth of unreleased studio recordings, photos, news clippings, scraps of paper containing lyrics in various drafts. Since he began slowly releasing this material in 2006, Young has created a portrait of an artist as almost preternaturally creative as he is obsessive. “Prolific” doesn’t even begin to describe his work in the ‘70s. Including his most recent massive archival set released on his website in November of 2020 (along with a 10-CD collector’s version), he has now released nine more new and complete albums from the ‘70s (seven live albums and two studio records) along with a live CSNY album, and additional material that comprises over 200 performances, including some 30 songs unreleased at the time of recording – and that’s only up through 1976! At least two more complete studio albums from the late ‘70s and another live set are promised in the coming years.

Dr. Daniel Levitin, a musician, neuroscientist and author of the bestseller “The Organized Mind,” once visited Young’s studio in the early ‘80s. Tim Mulligan, one of Young’s long-trusted recording engineers, showed him around. “He told me that Neil archived every tape himself and paid staff to catalog and inventory all of his master tapes and concert tapes,” says Levitin. “He wanted to have complete control over his archive and his output.”

The result of all that work – over 50 years of it – is that Young now reigns over what is surely the most vast and well-documented oeuvre in all of rock.

Which brings us back to that bit of film footage from the ‘70s. It, too, lives within the Neil Young Archives, and is screened there occasionally as part of a rotating set of video features shown on his site’s Hearse Theater. Watching it half a century later, one witnesses not just an artist protecting his assets, but a sophisticated, even obsessive self-chronicler who had someone film the whole scene, no doubt to be catalogued for who knows what use at a later date. Now, thanks the Archives, we know what use. And we know a lot more than that.

Some highlights from the archive include:

Wonderin’

A song he would eventually release on “Everybody’s Rockin’” in 1983, “Wonderin’” was first recorded for 1970’s “After The Goldrush.” Its jaunty melody wouldn’t have been a good fit for that album, but it makes for a great outtake that reveals the range of Young’s songwriting at the time.

Homefires

With a melody reminiscent of the Beatles’ “I’m A Loser,” 1974’s “Homefires” has figured in Young’s concerts at various points over the years, but never received a release until 2020, one of a slew of plaintive acoustic numbers from the period that can be found on the Archive’s site.

Give Me Strength

A heartbreak song this beautiful with a melody this memorable might be a career highlight for another songwriter. For Neil Young, it was just another acoustic outtake from 1974.

Separate Ways

Speaking of heartbreak, “Separate Ways” is a killer from a 1975 album called “Homegrown” that Young didn’t release at the time because he deemed the songs too personal. It came out in 2020, and it’s easy to hear why he thought that. (The beautiful drum pattern, by the way, is played by The Band’s Levon Helm.)

Vacancy

A song that provides an angry flipside to “Separate Ways,” this one is Young at his most ominous, and features a menacing guitar/harmonica vamp unlike anything else he ever put on tape … at least as far as we know.

Powderfinger

One of Young’s most beloved songs, originally released on “Rust Never Sleeps” in 1979, it was originally recorded four years earlier. This is a slower, rambling version that nonetheless still packs a punch.

Hawaii

Included in Young’s ‘70s output was a batch of compositions with lyrics so enigmatic – “Yonder Stands The Sinner,” “Ride My Llama,” and “Sedan Delivery” come to mind — that listeners were perhaps best served by providing their own meanings. “Hawaii” joins that group as another prime example.