In 1997, Bob Dylan was a Kennedy Center Honoree. Below is the text of a speech given by writer and music critic Tom Piazza for that occasion.

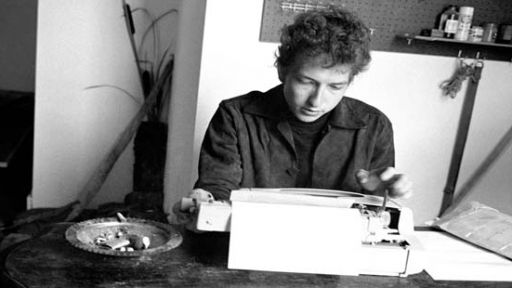

The central question for an American artist – both as an American and as an artist – is how to remain indivisibly oneself while, in Walt Whitman’s phrase, containing multitudes. Few in our time have done both as fully as Bob Dylan.

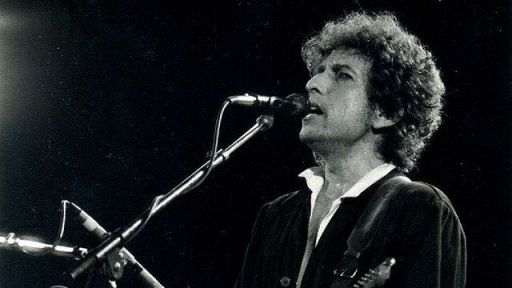

By now it probably goes without saying that he is the foremost American songwriter of the last 35 years. Even a short list of his best known songs, from “Blowin’ In the Wind” through “Mr. Tambourine Man” and the songs from classic albums like Highway 61 Revisited, Blood On The Tracks, Infidels and Time Out Of Mind, would take up half this page. In the course of writing and performing them he has changed everyone’s expectations of the kinds of complexity and meaning that popular songs could deliver.

But beyond his preeminence as a songwriter and performer, Bob Dylan has remained a quintessentially American artist in the largest sense, a true American original. By combining African-American blues, white country music, rural folk music, imagist poetry and rock and roll, Dylan created a new musical and literary form, both popular and serious at the same time, which many have emulated but of which Bob Dylan is still not only the prototype but the unchallenged master.

From the beginning, Dylan’s work has occupied a special, central ground where forms and genres that had previously been seen as separate or incompatible combined and were transmuted into something both wholly his own and wholly in the American grain. From many sources came one voice – E pluribus unum – and in his constant reimagining of these materials he has proved, over and over, that the elements of American culture, in all their contradictory, painful, exhilarating and sometimes indigestible glory, are infinitely elastic, and infinitely renewable.

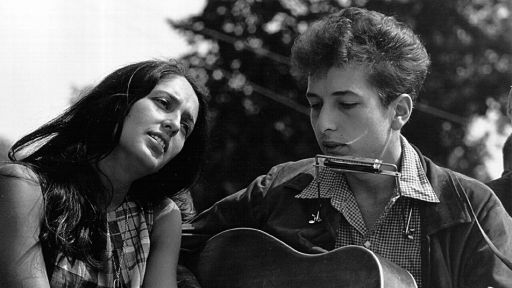

For years, reviewers of popular culture have reflexively referred to Bob Dylan as the voice, even the conscience of a generation. And it is true that the period of the 1960s, in nearly all of its aspects – its political and moral preoccupations, its apocalyptic overtones – was reflected in his recordings of the time as it was in no other single artist’s work, regardless of genre. Yet he has remained an abiding presence in American culture, his work growing and changing as he and the culture at large have grown and changed during the past three decades. He and his work represent something perennial in our culture.

“I always thought,” he said once, “that one man, the lone balladeer with the guitar, could blow an entire army off the stage if he knew what he was doing.” That sense of the power of the lone creative voice can be traced, its pulse felt, through the great river of creative imagery and action that stretches back centuries in the United States: traveling lecturers, tall-tale spinners, itinerant entertainers of all sorts, blues singers, old-time fiddlers. It is there to be heard in the work of Jimmie Rodgers and Blind Lemon Jefferson, Emily Dickinson and Bessie Smith, Walt Whitman and Jack Kerouac, the sense of the individual voice, intensely personal, indivisible, taking on American life, in all its epic contradictions.

In his song “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” on his 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home, the singer spins a long, tall yarn in which he arrives in North America before the arrival of Columbus and has a series of funny, dreamlike encounters, skirmishes, and near-misses with a gallery of bizarre characters. At the end of the song the singer greets Christopher Columbus himself as the explorer arrives on the continent, and Dylan wishes him a deadpan “good luck.”

It is a tall tale in a tradition going back to Mark Twain, and well before him, yet it is something more as well. In it we watch a vivid imagination cutting a mythic reality down to size – projecting itself, in fact, right into the middle of that reality. With wry humor, the singer celebrates a discovery of a land that is confusing and out of whack yet full of possibility, and claims, in a more than symbolic sense, the territory for his own.

There is a recognizable stance here, and in all of Dylan’s work: a sense that the individual sensibility – aesthetic, political, spiritual – could claim a role at the heart of the nation’s ongoing drama, in the middle of its ethnic and regional polyphony, locate what was of value there, and sing a new self, even a new country, out of it. As if the very activity of incorporating, coming to terms with, those multitudes of influence and utterance is itself somehow at the heart of the American ideal.

A large part of Dylan’s enduring claim on our imagination and attention is that his example has restated that ambition and that possibility, year after year, to this day. His has been an example not only to songwriters but to fiction writers, playwrights, poets, and filmmakers, constant proof that this culture, in all its contradictions, is still there to be claimed yet again, seen anew, through the agency of the human heart and imagination.