Below is an excerpt from the Bob Dylan autobiography Chronicles: Volume One published by Simon & Schuster.

The moon was rising behind the Chrysler Building, it was late in the day, street lighting coming on, the low rumble of heavy cars inching along in the narrow streets below-sleet tapping against the office window. Lou Levy was starting and stopping his big tape machine-diamond ring gleaming off his pinky finger-cigar smoke hanging in the blue air. The place was like a room used for interrogation, a fixture like a fruit bowl hanging overhead and a couple of lamps, some brass ones on floor stands. Below my feet a patterned wood floor. It was a drab room and cluttered with trade magazines-Cashbox, Billboard, radio survey charts-an ancient filing cabinet in the corner. Besides Lou’s old metal desk, there were a couple of wood chairs and I sat forward in one of them strumming songs off the guitar.

Recently I had called home. I did that at least a couple of times a month from one of the many public pay phones around town. The phone booths were like sanctuaries, step inside of them, shut the accordion type doors and you locked yourself into a private world free of dirt, the noise of the city blocked out. The phone booths were private, but the lines back home weren’t. Back there every household had a party line. About eight or ten different houses all used the same line, only with different numbers. If you’d pick up the phone receiver, seldom would the line ever be clear. There were always other voices. Nobody ever said anything important over the phone and you didn’t ramble on long. If you wanted to talk to people, you’d usually talk to them in the street, in vacant lots, fields or in cafes, never on the phone.

On the corner I put the dime in the slot and dialed the operator for long distance, called collect and the call went right through. I wanted everyone to know I was all right. My mother would usually give me the latest run of the mill stuff. My father had his own way of looking at things. To him life was hard work. He’d come from a generation of different values, heroes and music, and wasn’t so sure that the truth would set anybody free. He was pragmatic and always had a word of cryptic advice. “Remember, Robert, in life anything can happen. Even if you don’t have all the things you want, be grateful for the things you don’t have that you don’t want.” My education was important to him. He would have wanted me to become a mechanical engineer. But in school, I had to struggle to get even decent grades. I was not a natural student. My mom, bless her, who had always stood up for me and was firmly on my side in just about anything and everything, was more concerned about “a lot of monkey business out there in the world,” and would add, “Bobby, don’t forget you have relatives in New Jersey.” I’d already been to Jersey but not to visit relatives.

Lou snapped the big tape machine off after listening hard to one of my original songs. “Woody Guthrie, eh? That’s interesting. What made you want to write a song about him? I used to see him and his partner, Leadbelly-they used to play at the Garment Workers Hall over on Lexington Avenue. You ever heard ‘You Can’t Scare Me, I’m Sticking to the Union’?” Sure I’d heard it.

“Whatever happened to him, anyway?”

“Oh, he’s over in Jersey. He’s in the hospital there.”

Lou chomped away. “Nothing serious I hope. What other songs do you have? Let’s put ’em all down.”

I didn’t have many songs, but I was making up some compositions on the spot, rearranging verses to old blues ballads, adding an original line here or there, anything that came into my mind-slapping a title on it. I was doing my best, had to thoroughly feel I was earning my fee. Nothing would have convinced me that I was actually a songwriter and I wasn’t, not in the conventional songwriter sense of the word. Definitely not like the workhorses over in the Brill Building, the song chemistry factory that was only a few blocks away but might as well have been on the other side of the cosmos. Over there, they cranked out the home-run hits for radio playlists. Young songwriters like Gerry Goffin and Carole King, or Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, or Pomus and Shuman, Leiber and Stoller-they were the songwriting masters of the Western world, wrote all the popular songs, all the songs with crafty melodies and simple lyrics that came off as works of power over the airwaves. One of my favorites was Neil Sedaka because he wrote and performed his own songs. I never crossed paths with any of those people because none of the popular songs were connected to folk music or the downtown scene.

What I was into was the traditional stuff with a capital T and it was as far away from the mondo teeno scene as you could get. Into Lou’s tape recorder I could make things up on the spot all based on folk music structure, and it came natural. As far as serious songwriting went, the songs I could see myself writing if I was that talented would be the kinds of songs that I wanted to sing. Outside of Woody Guthrie, I didn’t see a single living soul who did it. Sitting in Lou’s office I rattled off lines and verses based on the stuff I knew-“Cumberland Gap,” “Fire on the Mountain,” “Shady Grove,” “Hard, Ain’t It Hard.” I changed words around and added something of my own here and there. Nothing do or die, nothing really formulated, all major chord stuff, maybe a typical minor key thing, something like “Sixteen Tons.” You could write twenty or more songs off that one melody by slightly altering it. I could slip in verses or lines from old spirituals or blues. That was okay; others did it all the time. There was little head work involved. What I usually did was start out with something, some kind of line written in stone and then turn it with another line-make it add up to something else than it originally did. It’s not like I ever practiced it and it wasn’t too thought consuming. Not that I would sing any of it onstage.

Lou had never heard any of this kind of thing before, so there was very little feedback from him. Once in a while he would stop the machine and have me start over on something. He’d say, “That’s catchy,” and then want me to do it again. When that happened, I usually did something different because I hadn’t paid attention to whatever I just sung, so I couldn’t repeat it like he just heard it. I had no idea what he was going to do with all this stuff. It was as anti-big mainstream as you could get. Leeds Music had published songs like “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” “C’est Si Bon,” “Under Paris Skies,” “All or Nothing at All,” Henry Mancini songs like “Peter Gunn,” “I’ll Never Smile Again” and all the songs that were in Bye Bye Birdie, a big Broadway hit.

The one song that had hooked me up with Leeds Music, the one that convinced John Hammond to bring me over there in the first place, wasn’t an outreaching song at all but more of an homage in lyric and melody to the man who’d pointed out the starting place for my identity and destiny-the great Woody Guthrie. I wrote the song with him in mind, and I used the melody from one of his old songs, having no idea that it would be the first of maybe a thousand songs that I would write. My life had never been the same since I’d first heard Woody on a record player in Minneapolis a few years earlier. When I first heard him it was like a million megaton bomb had dropped.

In the summer of ’59 after leaving home early spring, I was in Minneapolis, having come down from Northern Minnesota-from the Mesabi Range, the iron mining country, steel capital of America. I’d grown up there in Hibbing but had been born in Duluth, about seventy-five miles away to the east on the edge of Lake Superior, the big lake that the Indians call Gitche Gumee. Though we lived in Hibbing, my father from time to time would load us into an old Buick Roadmaster and we’d ride to Duluth for the weekend. My father was from Duluth, born and raised there. That’s where his friends still were. One of five brothers, he’d worked all his life even as a kid. When he was sixteen, he’d seen a car smash into a telephone pole and burst into flames. He jumped off his bicycle, reached in and pulled the driver out, smothering the driver’s body with his own-risking his life to save someone he didn’t even know. Eventually, he took accounting classes in night school and was working for Standard Oil of Indiana when I was born. Polio, which left him with a pronounced limp, had forced him out of Duluth-he lost his job and that’s how we got to the Iron Range, where my mother’s family was from. Near Duluth, I also had cousins across the suspension aerial bridge in Superior, Wisconsin, the notorious red-light, gambling town and I stayed with them sometimes.

What I recall mostly about Duluth are the slate gray skies and the mysterious foghorns, violent storms that always seemed to be coming straight at you and merciless howling winds off the big black mysterious lake with treacherous ten-foot waves. People said that having to go out onto the deep water was like a death sentence. Most of Duluth was on a slant. Nothing is level there. The town is built on the side of a steep hill, and you’re always either hiking up or down.

One time my parents took me to see Harry Truman speak at a political rally in Duluth’s Leif Erickson Park. Leif Erickson was a Viking who was supposed to have come to this part of country way before the Pilgrims had ever landed in Plymouth Rock. I must have been seven or eight at the time, but it’s amazing how I can still feel it. I can remember the excitement of being there in the crowd. I was on top of one of my uncles’ shoulders in my little white cowboy boots and cowboy hat. It was an exhilarating thing, being there-the cheers, the jubilation, the attentiveness to every word that Truman spoke . . . Truman was gray hatted, a slight figure, spoke in the same kind of nasal twang and tone like a country singer. I was mesmerized by his slow drawl and sense of seriousness and how people hung on every word he was saying. A few years later he would say that the White House was like a jail cell. Truman was down to earth. Once he even threatened a journalist who criticized his daughter’s piano playing. He didn’t do any of that in Duluth, though.

The upper Midwest was an extremely volatile, politically active area-with the Farmer Labor Party, Social Democrats, socialists, communists. They were hard crowds to please and not too much for Republicanism. John Kennedy, before he became president, when he was still a senator, had come up to Hibbing on the campaign trail but that was about six months after I left. My mother said that eighteen thousand people had turned out to see him at the Veterans Memorial Building and that people were hanging from the rafters and others were in the street, that Kennedy was a ray of light and had understood completely the area of the country he was in. He gave a heroic speech, my mom said, and brought people a lot of hope. The Iron Range was an area that very few nationally known politicians or any famous people ever made it through. (Woodrow Wilson had stopped there in the early part of the century and spoke from the back of a train. My mother had seen him, too, when she was ten years old.) If I had been a voting man, I would have voted for Kennedy just for coming there. I wished I could have seen him.

My mother’s family was from a little town called Letonia, just over the railroad tracks, not far from Hibbing. When she grew up the town consisted of a general store, a gas station, some horse stables, and a schoolhouse. The world I grew up in was a little different, a little more modernized, but still mostly gravel roads, marshlands, hills of ice, steep skylines of trees on the outskirts of town, thick forests, pristine lakes large and small, iron mine pits, trains and one-lane highways. Winters, ten below with a twenty below wind-chill factor were common, thawing spring and hot, steamy summers-penetrating sun and balmy weather where temperatures rose over one hundred degrees. Summers were filled with mosquitoes that could bite through your boots-winters with blizzards that could freeze a man dead. There were glorious autumns as well.

Mostly what I did growing up was bide my time. I always knew there was a bigger world out there but the one I was in at the time was all right, too. With not much media to speak of, it was basically life as you saw it. The things I did growing up were the things I thought everybody did-march in parades, have bike races, play ice hockey. (Not everyone was expected to play football or basketball or even baseball, but you had to know how to skate and play ice hockey.) The other usual things, too, like swimming holes and fishing ponds, sledding and something called bumper riding, where you grab hold of a tail bumper on a car and ride through the snow, Fourth of July fireworks, tree houses-a witches’ brew of pastimes. You could also easily hop an iron ore train by grabbing and then hanging on to one of the iron ladders on either side and ride out to any number of lakes where you could go out and jump in them. We did that a lot. As kids, we shot air guns, BB guns and the real thing-.22s-shot at tin cans, bottles or overfed rats in the town garbage dump. Also, we had rubbergun fights. Rubberguns were made from pine wood that were cut into L-shaped pieces. You’d grip the short end, which had a spring clothespin taped hard to the side. The rubber that we’d get from inner tubes back then was authentic, thick rubber that we’d cut into round strips, tie them in bows and stretch them from the hammer position, which was the top of the spring clothespin-stretch that all the way to the business end of the barrel. When you held the L-shaped gun in your grip (you could make them in varied sizes) and you squeezed it, the rubber would snap out with swift, violent force and you could hit a target to up to ten or fifteen feet away. You could hurt somebody. If you got hit with the rubber it stung like hell, burned and caused welts. These games would be played all day, one game after another. Usually you divided up sides in the beginning and hoped not to get popped in the eye. Some kids had three or four guns. If you got hit, you’d have to go to a certain spot under a tree and wait until the next game began. One year everything changed because the mines began using synthetic rubber on their tractors and trucks. Synthetic rubber wasn’t as good or as accurate as real rubber. It just dropped off the end of your barrel with a plop or else flew about four feet and flopped to the ground. This just wasn’t any good. I guess now, if you use real rubber, it would be like using dum-dum bullets.

Just about the same time that the synthetic rubber came into the picture, so did the big-screen drive-in movie. That was a family activity, though, because you had to have a car. There was other stuff going on. Dirt track stock car racing on cool summer nights, mostly ’49 or ’50 Fords, bashed in cars, coffin contraptions, humpbacked cages with roll bars and fire extinguishers-seats taken out, doors welded shut-bumpin’ and rumblin’, slammin’ and swivelin’ on a half mile track, summersaulting off the rails . . . tracks littered with junkyard cars. There were three-ring circuses that came to town a few times a year and full tilt carnivals complete with human oddities, showgirls and even geeks. I saw one of the last blackface minstrel shows at a county carnival. Nationally known country-western stars played at the Memorial Building, and once Buddy Rich and his big band came and played at the high school auditorium. The most thrilling event of the summer was when The King and His Court fast-pitch softball team came to town and challenged the best players in the county. If you liked baseball, this was the team to see. The King and His Court were four players: a pitcher, a catcher, a first baseman and a roving shortstop. The pitcher was awesome. Sometimes he pitched from second base, sometimes blindfolded, at times between his legs. Very few players ever got a hit off him, and The King and His Court never lost a game. Television was coming in, too, but not every home had one. Round picture tubes. Programs usually started broadcasting at about three o’clock in the afternoon with a test pattern that ran for a few hours and showed a few shows broadcast out of New York or Hollywood and then went off at around seven or eight. There wasn’t much to watch . . . Milton Berle, Howdy Doody, the Cisco Kid, Lucy and her Cuban bandleader husband, Desi, the Father Knows Best family, where everybody’s always dressed up even in their own house. It wasn’t like in the big city, where there was a lot more happening on TV. We didn’t get American Bandstand or anything like that. Of course, there were other things to do. Still, though, it was all small town stuff-very narrow, provincial, where everybody actually knows everyone. Now at last I was in Minneapolis where I felt liberated and gone, never meaning to go back. I’d come into Minneapolis unnoticed, I rode in on a Greyhound bus-nobody was there to greet me and nobody knew me and I liked it that way. My mother had given me an address for a fraternity house on University Avenue. My cousin Chucky, whom I just slightly knew, had been the fraternity president. He was four years older than me and an all-around successful student in high school-captain of the football team, valedictorian, class president. It was no surprise that he’d become president of the fraternity. My mom said that she talked to my aunt about calling Chucky and letting me stay there-at least while the place was vacated during the summer and most of its members were gone. There were a couple of guys hanging around when I got there and one of them said that I could stay in one of the upstairs rooms, the one at the end of the hall. It was a nothing room with just a bunk bed and a table by a window without any curtains. I set my bags down and gazed out the window.

I suppose what I was looking for was what I read about in On the Road-looking for the great city, looking for the speed, the sound of it, looking for what Allen Ginsberg had called the “hydrogen jukebox world.” Maybe I’d lived in it all my life, I didn’t know, but nobody ever called it that. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, one of the other Beat poets, had called it “The kiss proof world of plastic toilet seats, Tampax and taxis.” That was okay, too, but the Gregory Corso poem “Bomb” was more to the point and touched the spirit of the times better-a wasted world and totally mechanized-a lot of hustle and bustle-a lot of shelves to clean, boxes to stack. I wasn’t going to pin my hopes on that.

Creatively you couldn’t do much with it. I had already landed in a parallel universe, anyway, with more archaic principles and values; one where actions and virtues were old style and judgmental things came falling out on their heads. A culture with outlaw women, super thugs, demon lovers and gospel truths . . . streets and valleys, rich peaty swamps, with landowners and oilmen, Stagger Lees, Pretty Pollys and John Henrys-an invisible world that towered overhead with walls of gleaming corridors. It was all there and it was clear-ideal and God-fearing-but you had to go find it. It didn’t come served on a paper plate. Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified.

Folk music was all I needed to exist. Trouble was, there wasn’t enough of it. It was out of date, had no proper connection to the actualities, the trends of the time. It was a huge story but hard to come across. Once I’d slipped in beyond the fringes it was like my six-string guitar became a crystal magic wand and I could move things like never before. I had no other cares or interests besides folk music. I scheduled my life around it. I had little in common with anyone not like-minded.

I gazed out the second story window of the fraternity house overlooking University Avenue through the green elm trees and slow-moving traffic, low hanging clouds . . . the birds were singing. It was like a curtain was being lifted. It was early June and a fine spring day. There were just a few other guys in the house besides my cousin Chucky, and they hung around mostly in the mess hall, a kitchen in the basement that ran the length of the building. They had all recently graduated from the university and were working at odd jobs for the summer-were waiting to move on. Most days, they sat around playing cards and drinking beer in torn tee-shirts and cutoff jeans. Cocksmen. They paid me no mind. I saw that I could easily come and go and nobody would bother me here.

First thing I did was go trade in my electric guitar, which would have been useless to me, for a double-O Martin acoustic. The man at the store traded me even and I left carrying the guitar in its case. I would play this guitar for the next couple of years or so. The area around the university was known as Dinkytown, which was kind of like a little Village, untypical from the rest of conventional Minneapolis. It was mostly filled with Victorian houses that were being used as student apartments. School life wasn’t in session, so these were mostly empty. I found the local record store in the heart of Dinkytown. What I was looking for were folk music records and the first one I saw was Odetta on the Tradition label. I went into the listening booth to hear it. Odetta was great. I had never heard of her until then. She was a deep singer, powerful strumming and a hammering-on style of playing. I learned almost every song off the record right then and there, even borrowing the hammering-on style.

With my newly learned repertoire, I then went further up the street and dropped into the Ten O’Clock Scholar, a Beat coffeehouse. I was looking for players with kindred pursuits. The first guy I met in Minneapolis like me was sitting around in there. It was John Koerner and he also had an acoustic guitar with him. Koerner was tall and thin with a look of perpetual amusement on his face. We hit it off right away. We already knew a few of the same songs like “Wabash Cannonball” and “Waiting for a Train.” Koerner had just gotten out of the Marine Corps, was an aeronautical engineering student. He was from Rochester, New York, already married and had gotten into folk music a couple of years earlier than me, learned a lot of songs off of a guy named Harry Webber-mostly street ballads. But he played a lot of blues type stuff, too, traditional barroom kind of things. We sat around and I played my Odetta songs and a few by Leadbelly, whose record I had heard earlier than Odetta. John played “Casey Jones,” “Golden Vanity”-he played a lot of ragtime style stuff, things like “Dallas Rag.” When he spoke he was soft spoken, but when he sang he became a field holler shouter. Koerner was an exciting singer, and we began playing a lot together.

I learned a lot of songs off Koerner by singing harmony with him and he had folk records of performers I’d never heard at his apartment. I listened to them a lot, especially to The New Lost City Ramblers. I took to them immediately. Everything about them appealed to me-their style, their singing, their sound. I liked the way they looked, the way they dressed and I especially liked their name. Their songs ran the gamut in styles, everything from mountain ballads to fiddle tunes and railroad blues. All their songs vibrated with some dizzy, portentous truth. I’d stay with The Ramblers for days. At the time, I didn’t know that they were replicating everything they did off of old 78 records, but what would it have mattered anyway? It wouldn’t have mattered at all. For me, they had originality in spades, were men of mystery on all counts. I couldn’t listen to them enough. Koerner had some other key records, too, mostly on the Folkways label-Foc’sle Songs and Sea Shanties was one that I could listen to over and over again. This one featured Dave Van Ronk, Roger Abrams, and some others. The record knocked me out. It was full ensemble singing, hard driving harmonic songs like “Haul Away Joe,” “Hangin’ Johnny,” “Radcliffe Highway.” Sometimes Koerner and I sang some of those songs as a duo. Another record he had was the Elektra folk songs Sampler with a variety of artists. That’s where I first heard Dave Van Ronk and Peggy Seeger, even Alan Lomax himself singing the cowboy song “Doney Gal,” which I added to my repertoire. Koerner had a few other records-some blues compilations on the Arhoolie label where I first heard Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake, Charlie Patton and Tommy Johnson.

I listened a lot to a John Jacob Niles record, too. Niles was nontraditional, but he sang traditional songs. A Mephistophelean character out of Carolina, he hammered away at some harplike instrument and sang in a bone chilling soprano voice. Niles was eerie and illogical, terrifically intense and gave you goosebumps. Definitely a switched-on character, almost like a sorcerer. Niles was otherworldly and his voice raged with strange incantations. I listened to “Maid Freed from the Gallows” and “Go Away from My Window” plenty of times.

Koerner said that I had to meet a guy named Harry Webber and through him, I did. Webber was an English literary professor, a tweed wearing, old fashioned intellectual. And he did know plenty of songs, mostly roving ballads-stern ballads, ones that meant cruel business. I learned one called “Old Greybeard,” about a young girl whose mother tells her to go kiss a man who has been arranged for her to marry and the daughter tells the mother to go kiss him herself . . . that the old greybeard is now clean shaven. The song is sung in first, second and third person. I loved all these ballads right away. They were romantic as all hell and high above all the popular love songs I’d ever heard. You could exhaust all the combinations of your vocabulary without having to learn any vocabulary.

Lyrically they worked on some kind of supernatural level and they made their own sense. You didn’t have to make your own sense out of it. I used to sing another one, too, called “When a Man’s in Love,” where a boy in love feels no cold-he’ll go through frosted snow to meet his girl, get her and take her to some silent place. I was beginning to feel like a character from within these songs, even beginning to think like one. “Roger Esquire,” another song learned from Webber, was about money and beauty tickling the fancy and dazzling the eyes.

I could rattle off all these songs without comment as if all the wise and poetic words were mine and mine alone. The songs had beautiful melodies and were filled with everyday leading players like barbers and servants, mistresses and soldiers, sailors, farmhands and factory girls-their comings and goings-when they spoke in the songs they entered your life. But there was more to it than that . . . a lot more. Beneath it I was into the rural blues as well; it was a counterpart of myself. It was connected to early rock and roll and I liked it because it was older than Muddy and Wolf. Highway 61, the main thoroughfare of the country blues, begins about where I came from . . . Duluth to be exact. I always felt like I’d started on it, always had been on it and could go anywhere from it, even down into the deep Delta country. It was the same road, full of the same contradictions, the same one-horse towns, the same spiritual ancestors. The Mississippi River, the bloodstream of the blues, also starts up from my neck of the woods. I was never too far away from any of it. It was my place in the universe, always felt like it was in my blood.

Folklorist singers came through the Twin Cities also and you could learn songs from them, too-old-time performers like Joe Hickerson, Roger Abrams, Ellen Stekert or Rolf Kahn. Authentic folk records were as scarce as hens’ teeth. You had to know people who had them. Koerner and some others had them, but the group was very small. Record stores didn’t carry many of them, as there was very little demand. Performers like Koerner and myself would go anywhere to hear one by anybody we thought we hadn’t heard. We once went over to St. Paul to somebody’s house who supposedly had a 78 record of Blind Andy Jenkins singing “Death of Floyd Collins.” The person wasn’t at home and we never got to hear it. I did hear Tom Darby and Jimmy Tarleton, though, at the house of somebody’s father who had owned an old copy of one of their records. I always thought that “A-wop-bop-a-loo-lop a-lop-bam-boo” had said it all until I heard Darby and Tarlton doing “Way Down in Florida on a Hog.” Darby and Tarlton, too, were out of this world.

Koerner and I were playing and singing a lot together as a duo, but we each did our own thing separately. As for myself, I played morning, noon and night. That’s all I did, usually fell asleep with the guitar in my hands. I went through the entire summer this way. In the fall, I was sitting at the lunch counter at Gray’s drugstore. Gray’s drugstore was in the heart of Dinkytown. I had moved into a room right above it. School was back in session and university life was picking up again. My cousin Chucky and his buddies had all moved away from the fraternity house, and the fraternity members, or would-be fraternity members, soon reappeared. They asked me who I was and what I was doing there. Nothing, I wasn’t doing anything there . . . I was sleeping there. Of course I knew what was coming and quickly grabbed my bags and left. The room above Gray’s drugstore cost thirty bucks a month. It was an okay place and I could easily afford it.

By this time, I was making three to five dollars every time I played at either one of the coffeehouses around or another place over in St. Paul called the Purple Onion pizza parlor. Above Gray’s, the crash pad was no more than an empty storage room with a sink and a window looking into an alley. No closet or anything. Toilet down the hall. I put a mattress on the floor, bought a used dresser, plugged in a hot plate on top of that-used the outside window ledge as a refrigerator when it got cold. I was sitting at the counter at Gray’s one day-winter had come early-wind howled across the Central Avenue Bridge outside and a carpet of snow was beginning to form on the ground. Flo Castner, who I’d known from one of the coffeehouses, the Bastille, had come in and sat down beside me. Flo was an actress in the drama academy, an aspiring thespian, odd looking but beautiful in a wacky way, had long red hair, was light skinned, dressed in black from head to foot. She had an uptown but folksy demeanor, was a mystic and transcendentalist-believed in the occult power of trees and things like that. She was also serious about reincarnation.

We used to have strange conversations.

“In another life, I could have been you,” she’d say.

“Yeah, but then I wouldn’t have been the same person in that life.”

“Yeah, that’s right. Let’s work on it.”

On this particular day, we were just sitting around talking and she asked me if I’d ever heard of Woody Guthrie. I said sure, I’d heard him on the Stinson records with Sonny Terry and Cisco Houston. Then she asked me if I’d ever heard him all by himself on his own records. I couldn’t remember having done that. Flo said that her brother Lyn had some of his records and she’d take me over there to hear them-that Woody Guthrie was somebody that I should definitely get hip to. Something about this sounded important and I became definitely interested. There wasn’t much distance between the drugstore and her brother’s house, maybe a half a mile or so. Her brother Lyn was an attorney for the city’s social services-had thin, wispy hair, wore a bow tie and little James Joyce glasses. He had seen me and me him, a couple of times throughout the summer. I had heard him play a few folk songs, but he never said much and I never spoke to him. He had never invited me over to listen to anybody’s records.

He was at home when Flo brought me by. He said it was okay to look through his record collection, pulled out a few record albums of old 78s and said I should listen to these. One was the Spirituals to Swing Concert at Carnegie Hall. This was a collection of 78s with Count Basie, Meade Lux Lewis, Joe Turner and Pete Johnson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe among many others. The other collection was the one that Flo had told me about-a Woody Guthrie set of about twelve double sided 78 records. I put one on the turntable and when the needle dropped, I was stunned-didn’t know if I was stoned or straight. What I heard was Woody singing a whole lot of his own compositions all by himself . . . songs like “Ludlow Massacre,” “1913 Massacre,” “Jesus Christ,” “Pretty Boy Floyd,” “Hard Travelin’,” “Jackhammer John,” “Grand Coulee Dam,” “Pastures of Plenty,” “Talkin’ Dust Bowl Blues,” “This Land Is Your Land.”

All these songs together, one after another made my head spin. It made me want to gasp. It was like the land parted. I had heard Guthrie before but mainly just a song here and there-mostly things that he sang with other artists. I hadn’t actually heard him, not in this earth shattering kind of way. I couldn’t believe it. Guthrie had such a grip on things. He was so poetic and tough and rhythmic. There was so much intensity, and his voice was like a stiletto. He was like none of the other singers I ever heard, and neither were his songs. His mannerisms, the way everything just rolled off his tongue, it all just about knocked me down. It was like the record player itself had just picked me up and flung me across the room. I was listening to his diction, too. He had a perfected style of singing that it seemed like no one else had ever thought about. He would throw in the sound of the last letter of a word whenever he felt like it and it would come like a punch. The songs themselves, his repertoire, were really beyond category. They had the infinite sweep of humanity in them. Not one mediocre song in the bunch. Woody Guthrie tore everything in his path to pieces. For me it was an epiphany, like some heavy anchor had just plunged into the waters of the harbor.

That day I listened all afternoon to Guthrie as if in a trance and I felt like I had discovered some essence of self-command, that I was in the internal pocket of the system feeling more like myself than ever before. A voice in my head said, “So this is the game.” I could sing all these songs, every single one of them and they were all that I wanted to sing. It was like I had been in the dark and someone had turned on the main switch of a lightning conductor.

A great curiosity respecting the man had also seized me and I had to find out who Woody Guthrie was. It didn’t take me long. Dave Whittaker, one of the Svengali-type Beats on the scene happened to have Woody’s autobiography, Bound for Glory, and he lent it to me. I went through it from cover to cover like a hurricane, totally focused on every word, and the book sang out to me like the radio. Guthrie writes like the whirlwind and you get tripped out on the sound of the words alone. Pick up the book anywhere, turn to any page and he hits the ground running. Who is he? He’s a hustling ex-sign painter from Oklahoma, an antimaterialist who grew up in the Depression and Dust Bowl days-migrated West, had a tragic childhood, a lot of fire in his life-figuratively and literally. He’s a singing cowboy, but he’s more than a singing cowboy. Woody’s got a fierce poetic soul-the poet of hard crust sod and gumbo mud. Guthrie divides the world between those who work and those who don’t and is interested in the liberation of the human race and wants to create a world worth living in. Bound for Glory is a hell of a book. It’s huge. Almost too big.

His songs are something else, though, and even if you’ve never read the book, you’d know who he was through his songs. For me, his songs made everything else come to a screeching halt. I decided then and there to sing nothing but Guthrie songs. It’s almost like I didn’t have any choice. I liked my repertoire the way it was-stuff like “Cornbread, Meat and Molasses,” “Betty and Dupree,” “Pick a Bale of Cotton”-but I’d have to put it all on the back burner for a while, didn’t know if I’d ever get back to it. Through his compositions my view of the world was coming sharply into focus. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple. It seemed like a worthy thing. I even seemed to be related to him. Even from a distance and having never seen the man, I could perceive his face with a clearness. He looks not unlike my father in my father’s early days. I knew little about Woody. I wasn’t even sure if he was alive anymore. The book makes it seem like he was a character from the old past. Whittaker, though, had got me up to date on him, that he was in ill health somewhere in the East and I pondered that.

During the next few weeks I went back a few times to Lyn’s house to listen to those records. He was the only one who seemed to have so many of them. One by one, I began singing them all, felt connected to these songs on every level. They were cosmic. One thing for sure, Woody Guthrie had never seen nor heard of me, but it felt like he was saying, “I’ll be going away, but I’m leaving this job in your hands. I know I can count on you.”

Now that I crossed the divide, I was head over heels in singing nothing but Guthrie songs-at house parties, in the coffeehouses, street singing, with Koerner, not with Koerner-if I had a shower I would have sung them in there, too. There were a lot of them and outside of the main ones, not easily to be found. There were no reissues of his older records, there were only the original ones, but I would move heaven and earth to find them, even went to the Minneapolis public library to the Folkways section. (Public libraries were the one place for some reason that had most of the Folkways records.) I’d always be checking the repertoires of every out of town performer who came through to see what Guthrie songs they knew that I didn’t, and I was beginning to feel the phenomenal scope of Woody’s songs-the Sacco and Vanzetti ballads, Dust Bowl and children songs, Grand Coulee Dam songs, venereal disease songs, union and workingman ballads, even his rugged heartbreak love ballads. Each one seemed like a towering tall building with a variety of scenarios all appropriate for different situations. Woody made each word count. He painted with words. That along with his stylized type singing, the way he phrased, the dusty cowpoke deadpan but amazingly serious and melodic sense of delivery, was like a buzzsaw in my brain and I tried to emulate it any way I could. A lot of folks might have thought of Woody’s songs as backdated, but not me. I felt they were totally in the moment, current and even forecasted things to come. I felt anything but like the young punk folksinger who had just begun out of nowhere six months previously. It felt more like I had instantly risen up from a noncommissioned volunteer to an honorable knight-stripes and gold stars.

Woody’s songs were having that big an effect on me, an influence on every move I made, what I ate and how I dressed, who I wanted to know, who I didn’t. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, teenage rebellion was beginning to make noise, but that scene hadn’t appealed to me, not in a wholehearted way. It had no organized shape. The rebel-without-a-cause thing wasn’t hands-on enough-even a lost cause, I thought, would be better than no cause. To the Beats, the devil was bourgeois conventionality, social artificiality and the man in the gray flannel suit.

Folk songs automatically went up against the grain of all these things and Woody’s songs even went against that. In comparison, everything else seemed one-dimensional. The folk and blues tunes had already given me my proper concept of culture, and now with Guthrie’s songs my heart and mind had been sent into another cosmological place of that culture entirely. All the other cultures of the world were fine, but as far as I was concerned, mine, the one I was born into, did the work of them all and Guthrie’s songs even went further.

The sun had swung my way. I felt like I’d crossed the threshold and there was nothing in sight. Singing Woody’s songs, I could keep everything else at a safe distance. This fantasy was short-lived, however. Thinking that I was wearing the sharpest looking uniform and the shiniest boots around, all of a sudden I felt a jolt and was stopped short in my tracks. It felt like someone had taken a chunk out of me. Jon Pankake, a folk music purist enthusiast and sometime literary teacher and film wiseman, who’d been watching me for a while on the scene, made it his business to tell me that what I was doing hadn’t escaped him. “What do you think you’re doing? You’re singing nothing but Guthrie songs,” he said, jabbing his finger into my chest like he was talking to a poor fool.

Pankake was authoritative and a hard guy to get past. It was known around that Pankake had a vast collection of the real folk records and could go on and on about them. He was part of the folk police, if not the chief commissioner, wasn’t impressed with any of the new talent. To him nobody possessed any great mastery-no one could succeed in laying a hand on any of the traditional stuff with any authority. Of course he was right, but Pankake didn’t play or sing. It’s not like he put himself in any position to be judged.

He was a bit of a film critic, too. While other intellectual types might be discussing poetic differences between T. S. Eliot and e. e. cummings, Pankake would come up with arguments about why John Wayne was a better cowboy in Rio Bravo then he was in Legend of the Lost. He expounded on directors like Howard Hawks or John Ford, that they get Wayne when other directors don’t. Maybe Pankake was right, maybe not. It wasn’t that big a deal. Actually, as far as Wayne goes, I’d meet the Duke in the mid-’60s. He was the big male movie star at the time and was filming a war movie about Pearl Harbor, In Harm’s Way, over in Hawaii. A girl I used to know in Minneapolis, Bonnie Beecher, had become an actress and was playing a supporting role. Me and my band, The Hawks, had stopped through there on our way to Australia and she invited me down to the set, a naval battleship. She introduced me to the Duke, who was in full military uniform, an army of people surrounding him. I watched him film a scene and then Bonnie brought me over to meet him. “I hear you’re a folksinger,” he said and I nodded. “Sing something,” he said. I took out my guitar and sang “Buffalo Skinners” and he smiled, looked at Burgess Meredith who was sitting in a canvas chair, then he looked back at me and said, “I like that. Left that drover’s bones to bleach, heh?” “Yup.” He asked me if I knew “Blood on the Saddle.” I did know “Blood on the Saddle,” a little bit of it, anyway, but I knew “High Noon” better. I thought about singing it and maybe if I was standing there with Gary Cooper, I would have. But Wayne wasn’t Gary Cooper. I don’t know if he would have liked that song. The Duke was a massive figure. He looked like a heavy piece of hauled lumber, and it didn’t seem like any man could stand shoulder to shoulder with him. Not anybody in the movies, anyway. I thought of asking him why some of his cowboy films were better than others, but it would have been crazy to do that. Or maybe it wouldn’t have been . . . I don’t know. In any case, I never would have dreamed that I’d be standing there on a battleship, somewhere in the Pacific singing for the great cowboy John Wayne, while back in Minneapolis face-to-face with Jon Pankake . . .

“You’re trying hard, but you’ll never turn into Woody Guthrie,” Pankake says to me as if he’s looking down from some high hill, like something has violated his instincts. It was no fun being around Pankake. He made me nervous. He breathed fire through his nose. “You better think of something else. You’re doing it for nothing. Jack Elliott’s already been where you are and gone. Ever heard of him?” No, I’d never heard of Jack Elliott. When Pankake said his name, it was the first time I’d heard it. “Never heard of him, no. What does he sound like?” John said that he’d play me his records and that I was in for a surprise.

Pankake lived in an apartment above McCosh’s bookstore, a place that specialized in eclectic old books, ancient texts, philosophical political pamphlets from the 1800s on up. It was a neighborhood hangout for intellectuals and Beat types, on the main floor of an old Victorian house only a few blocks away. I went there with Pankake and saw it was true that he had all the incredible records, ones you never saw and wouldn’t know where to get. For someone who didn’t sing and play, it was amazing that he had so many. The record he took out and played for me first was Jack Takes the Floor on the Topic label out of London-an imported record, a very obscure one. There were probably only about ten of these discs in the whole U.S.A., or maybe Pankake had the only one in the country. I didn’t know. If Pankake hadn’t played it for me most likely I would have never heard it.

The record started to spin and Jack’s voice blasted into the room. “San Francisco Bay Blues,” “Ol’ Riley” and “Bed Bug Blues” go by in a flash. Damn, I’m thinking, this guy is really great. He sounds just like Woody Guthrie, only a leaner, meaner one, not singing the same Guthrie songs, though. I felt like I’d been cast into sudden hell.

Jack was some master of musical tricks. The record cover was mysterious, but not in an ominous way. It showed a character with certain careless ease, rakish looking, a handsome saddle tramp. He’s dressed like a cowboy. His tone of voice is sharp, focused and piercing. He drawls and he’s so confident it makes me sick. All that and he plays the guitar effortlessly in a fluid flat-picking perfected style. His voice leaps all over the room in a lazy way and he is explosive when he wants to be. You could hear that he had Woody Guthrie’s style down pat and more. Another thing-he was a brilliant entertainer, something that most of the folk musicians didn’t bother with. Most folk musicians waited for you to come to them. Jack went out and grabbed you. Elliott, who’d been born ten years before me, had actually traveled with Guthrie, learned his songs and style firsthand and had mastered it completely.

Pankake was right. Elliott was far beyond me. There were a few other Ramblin’ Jack records that he had, too-one where he sings with Derroll Adams, a singer buddy of his from Portland who played banjo like Bascom Lamar Lunsford and sang in a dry and laconic witted style suiting Jack perfectly. Together they sounded like horses galloping. They did “More Pretty Girls Than One,” “Worried Man Blues” and “Death of John Henry.” Jack alone was something else, though. On the cover of his record Jack Takes the Floor, you could almost see his eyes. They were saying something, but I knew not what. Pankake let me listen to the record repeated times. It was uplifting, but it was being thrown down at the same time. Pankake said something earlier, like Jack being the king of the folksingers, the city ones, anyway. Listening to him, you wouldn’t doubt it. I don’t know if Pankake was trying to enlighten me or put me down. It didn’t matter. Elliott had indeed already gone beyond Guthrie, and I was still getting there. I had nothing near the compelling poise of self that I heard on the record.

I sheepishly left the apartment and went back out into the cold street, aimlessly walked around. I felt like I had nowhere to go, felt like one of the dead men walking through catacombs. It would be hard not to be influenced by the guy I just heard. I’d have to block it out of my mind, though, forget this thing, tell myself I hadn’t heard him and he didn’t exist. He was overseas in Europe, anyway, in a self-imposed exile. The U.S. hadn’t been ready for him. Good. I was hoping he’d stay gone, and I kept hunting for Guthrie songs.

A few weeks later Pankake heard me playing again and was quick to point out that I didn’t fool him, that I used to be imitating Guthrie and now I was imitating Elliott and did I think in some way that I was equivalent to him? Pankake said that maybe I should go back to playing rock and roll, that he knew I used to do that. I don’t know how he knew-maybe he was a spy, too, but in any case, I wasn’t trying to fool anybody. I was just doing what I could with what I had where I was. Pankake was right, though. You can’t take only a few dance lessons and then think you are Fred Astaire.

Jon was one of the classic traditional folk snobs. They looked down on anything that smelled of commerciality and were vocal about it: groups like The Brothers Four, Chad Mitchell Trio, Journeymen, Highwaymen-the traditional folk snobs considered them all exploiters of a sacred thing. Okay, so that stuff didn’t give me orgasms either. But they were no threat, so I didn’t care about it one way or another. Most of the folk crowd trashed the commercial folk stuff. The popular perception of folk music were things like “Waltzing Matilda,” “Little Brown Jug” and “The Banana Boat Song” and all that stuff had appealed to me a few years earlier so I didn’t feel the need to put it down. To be fair, there were snobs on the other side, too-commercial folk snobs. These kind looked down on the traditional singers as being old-fashioned and wrapped in cobwebs. Bob Gibson, a clean-cut commercial folksinger from Chicago, had a big following and some records out. If he dropped in to see you perform he’d be in the front row. After the first or second song, if you weren’t commercial enough, too raw or ragged around the edges, he might conspicuously stand up, make a fuss and walk out on you. There wasn’t any middle ground and it seemed like everybody was a snob of one kind or another. I tried to keep everything in perspective.

Whatever I heard people say was irrelevant-both good or bad-didn’t get caught up in it. I had no preconditioned audience anyway. What I had to do was keep straight ahead and I did that. The road ahead had always been encumbered with shadowy forms that had to be dealt with in one way or another. Now there was another one. I knew Jack was up there someplace and I hadn’t missed what Pankake had said about him. It was true. Jack was the King of the Folksingers.

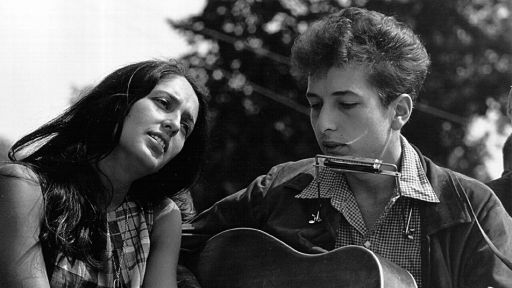

The “Queen of the Folksingers,” that would have to be Joan Baez. Joan was born the same year as me and our futures would be linked, but at this time to even think about it would be preposterous. She had one record out on the Vanguard label called Joan Baez and I’d seen her on TV. She’d been on a folk music program broadcast nationwide on CBS out of New York. There were other performers on the show including Cisco Houston, Josh White, Lightnin’ Hopkins. Joan sang some ballads on her own and then sat side by side with Lightnin’ and sang a few things with him. I couldn’t stop looking at her, didn’t want to blink. She was wicked looking-shiny black hair that hung down over the curve of slender hips, drooping lashes, partly raised, no Raggedy Ann doll. The sight of her made me high. All that and then there was her voice. A voice that drove out bad spirits. It was like she’d come down from another planet.

She sold a lot of records and it was easy to understand why. The women singers in folk music were performers like Peggy Seeger, Jean Ritchie and Barbara Dane, and they didn’t translate well to a modern crowd. Joan was nothing like any of them. There was no one like her. It would be a few years before Judy Collins or Joni Mitchell would come on the scene. I liked the older women singers-Aunt Molly Jackson and Jeanie Robinson-but they didn’t have the piercing quality that Joan had. I’d been listening to a few of the female blues singers a lot, like Memphis Minnie and Ma Rainey, and Joan was in some kind of way more like them. There was nothing girlish about them and there was nothing girlish about Joan, either. Both Scot and Mex, she looked like a religious icon, like somebody you’d sacrifice yourself for and she sang in a voice straight to God . . . also was an exceptionally good instrumentalist.

The Vanguard record was no phony baloney. It was almost frightening-an impeccable repertoire of songs, all hard-core traditional. She seemed very mature, seductive, intense, magical. Nothing she did didn’t work. That she was the same age as me almost made me feel useless. However illogical it might have seemed, something told me that she was my counterpart-that she was the one that my voice could find perfect harmony with. At the time there was nothing but distance and worlds and big divides between her and me. I was still stuck in the boondocks. Yet some strange feeling told me that we would inevitably meet up. I didn’t know much about Joan Baez. I had no idea that she’d always been a true loner, kind of like me, but she’d been bounced around a lot and lived in places from Baghdad to San Jose. She had experienced a whole lot more of the world than I did. Even so, to think that she was probably more like me than me would have seemed a little excessive.

There was no clue from her records that she was interested in social change or any of that. I considered her lucky, lucky to get involved in the right kind of folk music early on, get up to her eyeballs in it-learn how to play and sing it in an expert way, beyond criticism, beyond category. There was no one in her class. She was far off and unattainable-Cleopatra living in an Italian palace. When she sang, she made your teeth drop. Like John Jacob Niles, she was mighty strange. I’d be scared to meet her. She might bury her fangs in the back of my neck. I didn’t want to meet her, but I knew I would. I was going in the same direction even though I was way in back of her at the moment. She had the fire and I felt I had the same kind of fire. I could do the songs she did, for starters . . . “Mary Hamilton,” “Silver Dagger,” “John Riley,” “Henry Martin.” I could make them drop into place like she did, but in a different way. Not everyone can sing these songs convincingly. The singer has to make you believe what you are hearing and Joan did that. I believed that Joan’s mother would kill somebody that she loved. I believed that. I believed that she’d come from that kind of family. You have to believe. Folk music, if nothing else, makes a believer out of you. I believed Dave Guard in The Kingston Trio, too. I believed that he would kill or already did kill poor Laura Foster. I believed that he’d kill someone else, too. I didn’t think he was playing around.

As far as other singers around town, there were some but not many. There was Dave Ray, a high school kid who sang Leadbelly and Bo Diddley songs on a twelve-string guitar, probably the only twelve-string guitar in the entire Midwest-and then there was Tony Glover, a harp player who played with me and Koerner sometimes. He sang a few songs, but mostly played the harp-cupped it in his hands and played like Sonny Terry or Little Walter. I played the harp, too, but in a rack . . . probably the only harmonica rack at the time in the Midwest. Racks were impossible to find. I’d used a lopsided coat hanger for a while, but it only had sort of worked. The real harmonica rack that I found was in the basement of a music store on Hennipen Avenue, still in a box unopened from 1948. As far as harp playing went, I tended to keep it simple.

I couldn’t play like Glover or anything, and didn’t try to. I played mostly like Woody Guthrie and that was about it. Glover’s playing was known and talked about around town, but nobody commented on mine. The only comment that I ever got was a few years later in John Lee Hooker’s hotel room on Lower Broadway in New York City. Sonny Boy Williamson was there and he heard me playing, said, “Boy, you play too fast.”

Eventually, it was time for me to get out of Minneapolis. Just like Hibbing, the Twin Cities had gotten a little too cramped, and there was only so much you could do. The world of folk music was too closed off and the town was beginning to feel like a mud puddle. New York City was the place I wanted to be and one snowy morning around daybreak after sleeping in the back room of the Purple Onion pizza parlor in St. Paul, the place where Koerner and I played . . . with only a few tattered rags in a suitcase and a guitar and harmonica rack, I stood on the edge of town and hitchhiked east to find Woody Guthrie. He was still the man. It was freezing and although I might have been slack in a lot of things, my mind was ordered and disciplined and I didn’t feel the cold. Soon I was rolling through the snowy Wisconsin prairie fields, the looming shadows of Baez and Elliott were not far from my heels. The world I was heading into, although it would undergo a lot of changes, was really the world of Jack Elliott and Joan Baez. However true that might have been, I, too, had the axe in my hands and needed to tear out of there, head off to where life promised something more-felt that my own voice and guitar would be equal to the situation.

New York City, midwinter, 1961. Whatever I was doing was working out okay and I intended to stay with it, felt like I was closing in on something. I was playing on the regular bill at the Village Gaslight, the premier club on the carnivalesque MacDougal Street. When I began working there, the Gaslight was owned by John Mitchell, a renegade and raconteur, a Brooklynite. I only saw him a few times. He was ornery and combatant, had an exotic looking girlfriend who Jack Kerouac had based a novel on. Mitchell was already legendary. The Village was heavily Italian, and Mitchell hadn’t taken even one step back from the local mafiosos. It was a known fact that he didn’t make payoffs out of principle. The fire marshals, the police and the health inspectors were routinely invading the place. Mitchell, though, had lawyers and he took his battles to city hall and somehow the place stayed open. Mitchell carried a pistol and a knife. He also was a master carpenter. During my time there, some Mississippians bought the place sight unseen from a business opportunity ad in a magazine down South. Mitchell didn’t tell anybody he was selling the club or that it would change ownership. He just sold the place and left the country.

The gothic folk club was located in the basement below the street, but it didn’t seem like a basement because the floor had been lowered. About six or eight main performers alternated from darkness until dawn. The pay was sixty dollars weekly cash, at least that’s what it was for me. Some performers might have been paid more. It was a huge step above the Greenwich Village basket-house scene.

Noel Stookey who later became part of Peter, Paul and Mary was the MC. Noel was an impressionist, a comedian and a singer and guitar player. He worked in a camera store during the day. At night he was dressed in a neat three-piece suit, was immaculately groomed, a little goatee, tall and lanky, Roman nose. Some people might have described him as aloof. Stookey looked like someone torn out of a page of some ancient magazine. He could imitate just about anything-clogged water pipes and toilets flushing, steamships and sawmills, traffic, violins and trombones. He could imitate singers imitating other singers. He was very funny. One of his more outrageous imitations was Dean Martin imitating Little Richard.

Hugh Romney, who later became the psychedelic clown Wavy Gravy, also performed down there. When he was Hugh Romney, he was the straightest looking cat you’d ever seen-always smartly dressed, usually in Brooks Brothers light gray suits. Romney was a monologist, gave long, intimate, unestablishmentarian raps, had squinty eyes, you could never tell if they were closed or opened. It was as if his sight was impaired. He’d walk onstage, squint into the blue spotlight and begin talking like he had just taken a long voyage and come back from a distant realm-like he had just gotten here from Constantinople or Cairo and he was going to enlighten you into some archaic mystery. It wasn’t so much what he said, it was just in the way he said it. There were a few others around who did what he did, but Romney was the most known. Romney had been influenced by but was in no way on the same level as Lord Buckley.

Buckley was the hipster bebop preacher who defied all labels. No sulking Beat poet, he was a raging storyteller who did riffs on all kinds of things from supermarkets to bombs and the crucifixion. He did raps on characters like Gandhi and Julius Caesar. Buckley had even organized something called the Church of the Living Swing (a jazz church). With stretched out words, Buckley had a magical way of speaking. Everybody, including me, was influenced by him in one way or another. He died about a year before I got to town so I never got to see him; heard his records, though.

Some of the other musicians at the Gaslight were Hal Waters, an interpreter who sang folk songs in a refined way, John Wynn, who played gut-string guitar and sang folk songs in an operatic voice. Someone closer in temperament to me was Luke Faust, a five-string banjo player and singer who sang Appalachian ballads, another guy named Luke Askew, who later became an actor in Hollywood. Luke was from Georgia and he sang Muddy and Wolf and Jimmy Reed songs. He didn’t play guitar but he had a guitar player. Luke was a white guy who sounded like Bobby Blue Bland.

Len Chandler played at the Gaslight, too. Len had originally come from Ohio and was a serious musician who had played oboe in the orchestra back home and could read and write and arrange symphonic music. He sang quasi-folk stuff with a commercial bent and was energetic, had that thing that people call charisma. Len performed like he was mowing down things. His personality overrode his repertoire. Len also wrote topical songs, front-page things.

Paul Clayton occasionally played sets down here, too. Paul got all his versions of songs by adapting transcriptions from old texts. He knew hundreds of songs and must have had a photographic memory. Clayton was unique-elegiac, very princely-part Yankee gentleman and part Southern rakish dandy. He dressed in black from head to foot and would quote Shakespeare. Clayton traveled regularly from Virginia to New York and back, and we got to be friends. His companions were out-of-towners and like him, a “caste apart”-had attitudes, but known only to themselves-a non-folky crowd.

Authentic nonconformists-scufflers, but not the Kerouac types, not down and outers, not the kind that run the streets whose activities could be recognized. I liked Clayton and I liked his friends. Through Paul I met people here and there who said to me it was okay to stay at their apartments any time I needed it, and not to worry about it.

Clayton was good friends with Van Ronk, too. Dave Van Ronk, he was the one performer I burned to learn particulars from. He was great on records, but in person he was greater. Van Ronk was from Brooklyn, had seaman’s papers, a wide walrus mustache, long brown straight hair which flew down covering half his face. He turned every folk song into a surreal melodrama, a theatrical piece-suspenseful, down to the last minute. Dave got to the bottom of things. It was like he had an endless supply of poison and I wanted some . . . couldn’t do without it. Van Ronk seemed ancient, battle tested. Every night I felt like I was sitting at the feet of a timeworn monument. Dave sang folk songs, jazz standards, Dixieland stuff and blues ballads, not in any particular order and not a superfluous nuance in his entire repertoire. Songs that were delicate, expansive, personal, historical, or ethereal, you name it. He put everything into a hat and-presto-put a new thing out in the sun. I was greatly influenced by Dave. Later, when I would record my first album, half the cuts on it were renditions of songs that Van Ronk did. It’s not like I planned that, it just happened. Unconsciously I trusted his stuff more than I did mine.

Van Ronk’s voice was like rusted shrapnel and he could get a lot of subtle ramifications out of it-delicate, gentle, rough, explosive, sometimes all within the same song. He could conjure up anything-expressions of terror, expressions of despair. He also was an expert guitar player. All that, and he had a sardonic humorous side, too. I felt different towards Van Ronk than anyone else on the scene because it was him who brought me into the fold and I was happy to be playing alongside him night after night at the Gaslight. It was a real stage with a real audience and it was where the real action was. Van Ronk helped me in other ways, too. His apartment on Waverly Place had a couch I could crash on any time I wanted to. He also showed me around the regular haunts of Greenwich Village-the other clubs, mostly jazz clubs like Trudy Heller’s, the Vanguard, the Village Gate and the Blue Note, and I got to see a lot of the jazz greats close up. As a performer Van Ronk did something else that I found intriguing.

One of his patented dramatic effects would be to stare intently at somebody in the crowd. He’d pin their eyes like he was singing just to them, whispering some secret, telling somebody something where their lives hung in the balance. He also never phrased the same thing the same way twice. Sometimes I’d hear him play the same song that he’d done in a previous set and it would hit me in a completely different way. He’d play something, and it was like I’d never heard it before, or not quite the way I remembered it. His pieces were perversely complex, although very simple. He had it all down and could hypnotize an audience or stun them, or he could make them scream and holler. Whatever he wanted. He was built like a lumberjack, drank hard, said little and had his territory staked out-full forward, all cylinders working. David was the grand dragon. If you were on MacDougal Street in the evening and out to see somebody play, he’d be the first and last vital choice of the night. He’d towered over the street like a mountain but would never break into the big time. It just wasn’t where he pictured himself. He didn’t want to give up too much. No puppet strings on him ever. He was big, sky high, and I looked up to him. He came from the land of giants.

Van Ronk’s wife, Terri, definitely not a minor character, took care of Dave’s bookings, especially out of town, and she began trying to help me out. She was just as outspoken and opinionated as Dave was, especially about politics-not so much the political issues but rather the highfalutin’ theological ideas behind political systems. Nietzschean politics. Politics with a hanging heaviness. Intellectually it would be hard to keep up. If you tried, you’d find yourself in alien territory. Both were anti-imperialistic, antimaterialist. “What a ridiculous thing, an electric can opener,” Terri once said as we walked past the shop window of a hardware store on 8th Street. “Who’d be stupid enough to buy that?”

Terri had managed to get Dave booked in places like Boston and Philly . . . even as far away as St. Louis at a folk club called Laughing Buddha. For me, those gigs were out of the question. You needed at least one record out even if it was on a small label to get work in any of those clubs. She did manage to come up with a few things in places like Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Hartford-once at a folk club in Pittsburgh, another in Montreal. Scattered things. Mostly I stayed around in New York City. I didn’t really want to go out of town. If I wanted to be out of town, I wouldn’t have come to New York City in the first place. I was fortunate to have the regular gig at the Gaslight and wasn’t on any wild goose chase to go anywhere. I could breathe. I was free. Didn’t feel constrained. Between sets I mostly hung out, drank shooters of Wild Turkey and iced Schlitz at the Kettle of Fish Tavern next door and played cards upstairs at the Gaslight. Things were working out fine. I was learning all I could and stayed keyed up. Once Terri offered to bring me over to meet Jac Holzman, who operated Elektra Records, one of the companies that released some of Dave’s stuff. “I can get you an appointment. Do you want to sit down with him?” “I don’t want to sit down with anybody, no.” The idea didn’t contain too much for me. Sometime later in the summer Terri managed to get me on a live radio folk extravaganza broadcast from Riverside Church up on Riverside Drive. Things were about to change for me again, to get new and strange.

Backstage the humidity was soaring. Performers came and went, waited to go on and milled around. As usual, the real show was backstage. I was talking to a dark-haired girl, Carla Rotolo, who I knew a little bit. Carla was Alan Lomax’s personal assistant. Carla introduced me to her sister. Her sister’s name was Susie but she spelled it Suze. Right from the start I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She was the most erotic thing I’d ever seen. She was fair skinned and golden haired, full-blood Italian. The air was suddenly filled with banana leaves. We started talking and my head started to spin. Cupid’s arrow had whistled by my ears before, but this time it hit me in the heart and the weight of it dragged me overboard. Suze was seventeen years old, from the East Coast. Had grown up in Queens, raised in a left-wing family. Her father had worked in a factory and had recently died. She was involved in the New York art scene, painted and made drawings for various publications, worked in graphic design and in Off-Broadway theatrical productions, also worked on civil rights committees-she could do a lot of things.

Meeting her was like stepping into the tales of 1,001 Arabian nights. She had a smile that could light up a street full of people and was extremely lively, had a particular type of voluptuousness-a Rodin sculpture come to life. She reminded me of a libertine heroine.

She was just my type.

For the next week or so I thought of her a lot-couldn’t shut her out of my mind, was hoping I’d run into her. I felt like I was in love for the first time in my life, could feel her vibe thirty miles away-wanted her body next to mine. Now. Right now. Movies had always been a magical experience and the Times Square movie theaters, the ones like oriental temples were the best places to see them. Recently I’d seen Quo Vadis and The Robe, and now I went to sit through Atlantis, Lost Continent and King of Kings. I needed to shift my mind, get it off of Suze for a while. King of Kings starred Rip Torn, Rita Gam, and Jeffrey Hunter playing Christ. Even with all the heavy action on the screen, I couldn’t tune into it. When the second feature, Atlantis, Lost Continent played, it was just as bad. All the death-ray crystals, giant fish submarines, earthquakes, volcanoes and tidal waves and whatnot. It might have been the most exciting movie of all time, who knows? I couldn’t concentrate.

As fate would have it, I ran into Carla again and asked about her sister. Carla asked me if I’d like to see her. I said, “Yeah, you don’t know how much,” and she said, “Oh, she’d like to see you, too.” Soon we met up and began to see each other more and more. Eventually we got to be pretty inseparable. Outside of my music, being with her seemed to be the main point in life. Maybe we were spiritual soul-mates.

Her mother Mary, though, who worked as a translator for medical journals, wasn’t having it. Mary lived on the top floor of an apartment building on Sheridan Square and treated me like I had the clap. If she would have had her way, the cops would have locked me up. Suze’s mom was a small feisty woman-volatile with black eyes like twin coals that could burn a hole through you, was very protective. Always make you feel like you did something wrong. She thought I had a nameless way of life and would never be able to support anybody, but I think it went much deeper than that. I think I just came in at a bad time.

“How much did that guitar cost?” she asked me once.

“Not much.”

“I know, not much, but still something.”

“Almost nothing,” I said.

She glared at me, cigarette in her mouth. She was always trying to goad me into some kind of argument. My presence was so displeasing to her, but it’s not like I’d caused any trouble in her life. It wasn’t me who was responsible for the loss of Suze’s father or anything. Once I said to her that I didn’t think she was being fair. She stared squarely into my eyes like she was staring at some distant, visible object and said to me, “Do me a favor, don’t think when I’m around.” Suze would tell me later that she didn’t mean it. She did mean it, though. She did everything in her power to keep us apart, but we went on seeing each other anyway.

This stifling scene was becoming problematic, signaling to me that I needed to get my own place, one with my own bed, stove and tables. It was about time. I guess it could have happened earlier, but I liked staying with others. It was less of a hassle, easier, with little responsibility-places where I could freely come and go, sometimes even with a key, rooms with plenty of hardback books on shelves and stacks of phonograph records. When I wasn’t doing anything else, I’d thumb through the books and listen to records.

Not having a place of my own now was beginning to affect my supersensitive nature, so after being in town close to a year, I rented a third floor walk-up apartment at 161 West 4th Street at sixty dollars a month. It wasn’t much, just two rooms above Bruno’s spaghetti parlor, next door to the local record store and a furniture supply shop on the other side. The apartment had a tiny bedroom, more like a large closet, and a kitchenette, a living room with a fireplace and two windows that looked out over fire escapes and small courtyards. There was barely room enough for one person and the heat went off after dark and the place had to be heated by keeping both gas burners up full blast. It came empty. Quickly after moving in I built some furniture for the place. With some borrowed tools, I made a couple of tables, one which doubled as a desk. I also put together a cabinet and a bed frame. All the wood pieces had come from the store downstairs, and I fastened everything together with the accompanying hardware-galvanized nails, knockers and hinge plates, 3/8-inch square pieces of wrought iron, brass and copper, roundheaded wood screws. I didn’t have to go far to get that stuff, it was all downstairs. I put it all together with hacksaws, cold chisels and screwdrivers-even made a couple of mirrors using an old technique I learned in a high school shop woodworking class using plates of glass, mercury and tin foil.

Besides playing music, I liked doing those kinds of things. I purchased a used TV, stuck it on top of one of the cabinets, bought a mattress and got a rug that I spread across the hardwood floor. I got a record player at Woolworth’s and put it on one of the tables. The small room seemed immaculate to me and I felt that for the first time I had a place of my own.

Suze and I were spending more and more time together, and I began to broaden my horizons, see a lot of what her world was like, especially the Off-Broadway scene . . . a lot of LeRoi Jones’s stuff, Dutchman, The Baptism. I also saw Gelber’s junkie play, The Connection, the Living Theater’s The Brig, and other remarkable plays. I went with her to where the artists and painters hung out, like Caffe Cino, Camino Gallery, Aegis Gallery. We went to see Comedia Del’Arte, a storefront on the Lower East Side that was built into a small theater with enormous puppets as big as people that jiggled and swung. I saw a couple of plays, one where a soldier, a prostitute, a judge and a lawyer were all the same puppet. The puppets, because of their size and the small, confining space, were odd, unsettling and confronting . . . nothing like the funny wooden dummy, the tuxedoed Charlie McCarthy, the Edgar Bergen puppet who we all knew and loved so well.

A new world of art was opening up my mind. Sometimes early in the day we’d go uptown to the city museums, see giant oil-painted canvases by artists like Velázquez, Goya, Delacroix, Rubens, El Greco. Also twentieth-century stuff-Picasso, Braque, Kandinsky, Rouault, Bonnard. Suze’s favorite current modernist artist was Red Grooms, and he became mine, too. I loved the way everything he did crushed itself into some fragile world, the rickety clusters of parts all packed together and then, standing back, you could see the complex whole of it all. Grooms’s stuff spoke volumes to me. He was the artist I checked out most. Red’s stuff was extravagant, his work cut like it was done by acid. All of his mediums-crayon, watercolor, gouache, sculpture or mixed media-collage tableaus-I liked the way he put the stuff together. It was bold, announced its presence in glaring details. There was a connection in Red’s work to a lot of the folk songs I sang. It seemed to be on the same stage. What the folk songs were lyrically, Red’s songs were visually-all the bums and cops, the lunatic bustle, the claustrophobic alleys-all the carnie vitality. Red was the Uncle Dave Macon of the art world. He incorporated every living thing into something and made it scream-everything side by side created equal-old tennis shoes, vending machines, alligators that crawled through sewers, dueling pistols, the Staten Island Ferry and Trinity Church, 42nd Street, profiles of skyscrapers. Brahman bulls, cowgirls, rodeo queens and Mickey Mouse heads, castle turrets and Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, creeps and greasers and weirdos and grinning, bejeweled nude models, faces with melancholy looks, blurs of sorrow-everything hilarious but not jokey. Familiar figures from history, too-Lincoln, Hugo, Baudelaire, Rembrandt-all done with graphic finesse, burned out as powerful as possible. I loved the way Grooms used laughter as a diabolical weapon. Subconsciously, I was wondering if it was possible to write songs like that.

About that time I began to make some of my own drawings. I actually picked up the habit from Suze, who drew a lot. What would I draw? Well, I guess I would start with whatever was at hand. I sat at the table, took out a pencil and paper and drew the typewriter, a crucifix, a rose, pencils and knives and pins, empty cigarette boxes. I’d lose track of time completely. An hour or two could go by and it would seem like only a minute. Not that I thought that I was any great drawer, but I did feel like I was putting an orderliness to the chaos around-something like Red did, but he did it on a much grander level. In a strange way I noticed that it purified the experience of my eye and I would make drawings of my own for years to come.