Singer-songwriter Bob Dylan’s enigmatic career has captivated audiences for decades. Writer Tom Casciato dissects Dylan’s most recent installment of the Never Ending Tour and the artist’s evolving persona.

Bob Dylan was 47 in 1988 when he began playing a relentless schedule of live dates, now known as the Never Ending Tour. Anyone who’s been going fairly regularly to his shows these past decades, as I have, has pretty much seen it all: Dylan being great; Dylan being far from great; Dylan radically rearranging his classics; Dylan introducing a new song or two. Often there would be some minimalist, cryptic comment from the stage that may or may not have been intended as funny. Those who don’t value his work as highly as I do might wonder why someone keeps going back to see him again and again. For me, the reason is somewhat mysterious: no matter how many times I’ve seen Bob Dylan in concert — the feeling usually hits me shortly after he leaves the stage and the house lights come up — I always end up feeling like I’ve never seen him before.

Maybe this isn’t altogether unsurprising. Despite his multitude of accomplishments — the Nobel Prize and all that — Dylan always feels like a work in progress, not just reimagining his compositions, but reimagining himself as some new kind of temporary vessel that the words and the music just flow through before it disappears. Not to mention the fact that this is the guy they made a movie about called “I’m Not There” (2007). But this sense of not having seen him is unnerving nonetheless, particularly, even ironically, because I have such strong memories of his performances.

I remember a show in Portland in 1993 where Dylan was far less than great, erratic even. I was sitting nowhere near the stage, but even from the cheap seats it appeared to me that the drummer, Winston Watson, was playing defense all night, sticks in the air, wondering when Dylan would change chords, hoping, I was certain, that it would be on the beat. Dylan’s solo acoustic set was flat, uninspired. The whole event was a shambles.

Just a year later at a show at the old Roseland Ballroom in New York City it was another story altogether. Dylan and the band were more disciplined. There were still rough elements — notably, Dylan’s idiosyncratic, sometimes wandering lead guitar stylings — but overall it was a tight and muscular show: Dylan at his best.

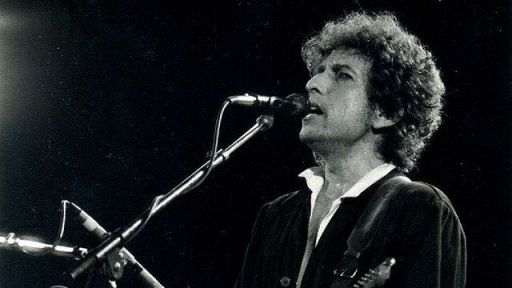

Which brings me to his current tour, which I caught at New York’s Beacon Theatre in November. It felt like a particularly special occasion, the Never Ending Tour having been temporarily ended by Covid-19. Not only that, the word was out that Dylan was skipping the classics that are often his concert staples — no “Like A Rolling Stone,” no “All Along The Watchtower,” no “Tangled Up In Blue” — and instead was introducing no fewer than eight new compositions at each show, all from his 2020 album “Rough And Rowdy Ways.” Oh, and he had recently turned 80.

Dylan. Eight new songs. 80. Finally, a show that I genuinely hadn’t seen before.

And there were, of course, the requisite rearrangements of older songs. “Serve Somebody” had none of the snaking menace of the original version — rather it rocked. As one of my companions at the show, the writer Bruce Handy said, it sounded more like a rave-up from Dave Edmonds and Nick Lowe’s Rockpile than anything on “Slow Train Coming.” The sweet “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” from “Nashville Skyline” was also turned into a full-on rocker. And the folky “When I Paint My Masterpiece” became a swing number (complete with Bob’s idiosyncratic, wandering piano stylings, which in recent years have taken the place of his aforementioned guitar work).

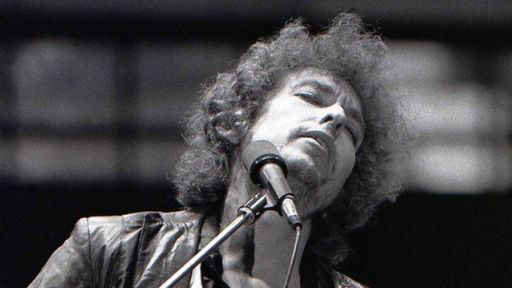

But on this night, it was the new tunes that mattered the most. For “False Prophet,” one of the strongest, Dylan got out from behind the piano, took the mic in hand and assumed a kind of poised crouch. Was it the bent posture of a man a few generations past his prime? Or that of a prize fighter ready to take a punch and return one far more devastating? Or both? Whatever it was, as he growled out the verses he seemed to have arrived on a mission:

Well I’m the enemy of treason

Enemy of strife

I’m the enemy of the unlived, meaningless life

I ain’t no false prophet

I just know what I know

I go where only the lonely can go

Was he telling us that if he isn’t a false prophet, he must be . . . a prophet? That’s a title he was saddled with throughout the 1960s, one he never quite rejected. Maybe, at 80, he had come to claim it.

Bob Dylan sings “The Times They Are A-Changin” Feb. 9, 2010. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Or maybe not. His new songs, which break no original melodic ground, mostly serve as sturdy vehicles that transport verses full of pop culture references and the many moods of a poet who has yet to run out of fuel. Dylan is rueful. Dylan is regretful. Dylan is philosophical. Dylan is threatening to hurt, or maybe kill you. (Go home to your wife, stop visiting mine / One of these days I’ll forget to be kind).

Whatever the mood, Dylan delivered each new number with a vitality suggesting these tunes mean as much to him as anything he’s ever written. And that spirit was infectious: the audience responded as enthusiastically for the new stuff as they did for the old. (Think of what a rarity that is at a show with an audience full of Baby Boomers!)

And there was even a hard-to-figure comment towards the end, something about New York City being the home of both Herman Melville and Sylvester Stallone. I figured that one as funny for sure, until Dylan told everyone they should have seen Stallone’s latest movie, “Last Blood” (actually entitled “Rambo: Last Blood,“ and in fact not his latest movie) and went on to lament that it should have won an Oscar (which it shouldn’t have). I immediately changed my assessment to the usual “cryptic.”

It all added up to the most satisfying Bob Dylan show I’ve seen in years, maybe decades. You can take my word for it — although I’m not altogether sure that I can take my word for it. You see, there are tapes circulating of those performances I saw in the ‘90s. The ’93 recordings from Oregon sound no less tight than what I heard in ’94. Similarly, the New York recordings are far more ragged than I remember. My memory tells me one story, the music another — which makes its own kind of sense.

After all, I’ve never seen him before.