This excerpt was written by Richard Zoglin and originally published in the introduction to his biography, Hope.

Memorials to Hope have proliferated across the American landscape. You can walk down streets named for Bob Hope in El Paso, Texas, Miami, Florida, and Branson, Missouri; cross the Cuyahoga River on the Hope Memorial Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio; and bypass the congestion at Los Angeles International by flying into the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, California. Hope’s name is memorialized on hospitals, theaters, chapels, schools, performing arts centers, and American Legion posts from Miami to Okinawa. The US Air Force named a transport plane for him, and the Navy christened a cargo ship in his honor. Bob Hope Village, in Shalimar, Florida, provides a home for retired members of the Air Force and their surviving spouses. The World Golf Hall of Fame, in St. Augustine, Florida, features an exhibit celebrating Hope’s passion for the game, “Bob Hope: Shanks for the Memory.” A dozen colleges offer scholarships in Hope’s name. Another dozen organizations give out awards in his honor, among them the Air Force’s annual Spirit of Hope Award and the Bob Hope Humanitarian Award, presented by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences.

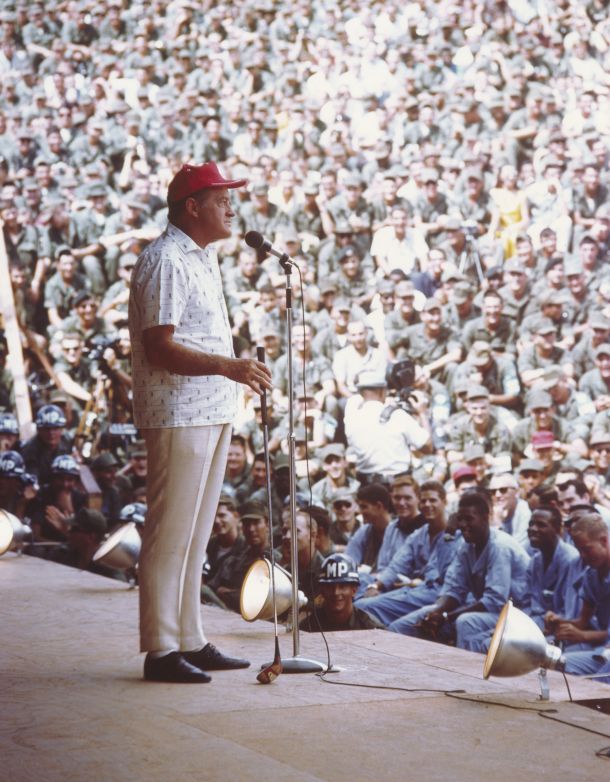

His punchy, two-syllable name, so emblematic of the optimistic American spirit; the unmistakable profile, with its jutting chin and famously ski-slope-shaped nose; the indelible images of Hope performing for throngs of cheering GIs in World War II and Vietnam—it was once impossible to imagine a time when the first question that needed to be answered about the most popular comedian in American history would be: Who was Bob Hope, and why did he matter?

Danang 1969 – Bob Hope Special: Around the Globe with the USO

By the time he died—on July 27, 2003, two months after his hundredth birthday—Hope’s reputation was already fading, tarnished, or being actively disparaged. He had, unfortunately, stuck around too long. The comedian of the century, who began his vaudeville career in the 1920s and was still headlining TV specials in the 1990s, continued performing well into his dotage, and a younger generation knew him mainly as a cue-card-reading antique, cracking dated jokes about buxom beauty queens and Gerald Ford’s golf game. “World’s Last Bob Hope Fan Dies of Old Age,” the Onion’s fake headline announced a year before his death. Writer Christopher Hitchens expressed the disaffection of many of the baby-boom generation in an online dismissal of Hope just a few days after his passing: “To be paralyzingly, painfully, hopelessly unfunny is a serious drawback, even lapse, in a comedian. And the late Bob Hope devoted a fantastically successful and well-remunerated lifetime to showing that a truly unfunny man can make it as a comic. There is a laugh here, but it is on us.”

Hope never recovered from the Vietnam years, when his hawkish defense of the war, close ties to President Nixon (who actively courted Hope’s help in selling his Vietnam policies to the American people), and the country-club smugness of his gibes about antiwar protesters and long-haired hippies, all made him a political pariah for the peace-and-love generation. His tours to entertain US troops during World War II had made him a national hero. By the turbulent 1960s, he was a court-approved jester, the Establishment’s comedian—hardly a badge of honor in an era when hipper, more subversive comics, from Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce to George Carlin and Richard Pryor, were showing that stand-up comedy could be a vehicle for personal expression, social criticism, and political protest. Even before Hope became a doddering relic, he had become an anachronism.

Yet the scope of Hope’s achievement, viewed from the distance of a few years, is almost unimaginable. By nearly any measure, he was the most popular entertainer of the twentieth century, the only one who achieved success — often No. 1–rated success — in every major genre of mass entertainment in the modern era: vaudeville, Broadway, movies, radio, television, popular song, and live concerts. He virtually invented stand-up comedy in the form we know it today. His face, voice, and stage mannerisms (the nose, the lopsided smile, the confident, sashaying walk, and the ever-present golf club) made him more recognizable to more people than any other entertainer since Charlie Chaplin. A tireless stage performer who traveled the country and the world for more than half a century doing live shows for audiences in the thousands, he may well have been seen in person by more people than any other human being in history.

His achievements as an entertainer, however, only hint at the breadth and depth of his impact. For the way he marketed himself, managed his celebrity, cultivated his brand, and converted his show-business fame into a larger, more consequential role for himself on the public stage, Bob Hope was the most important entertainer of the century. Viewed from the largest historical perspective—the way he intersects with the grand themes of the century, from the Greatest Generation’s crusade to preserve democracy in World War II, to the social, political, and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s—one could argue, without too much exaggeration, that he was the only important entertainer.

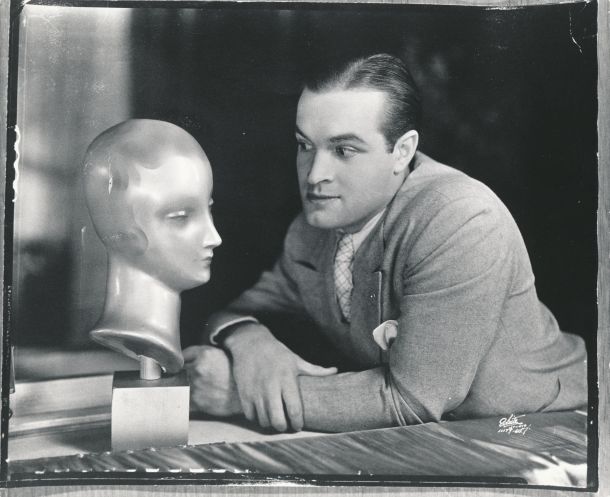

Nov. 21, 1933 – Bob Hope from “Roberta”

His life almost perfectly spanned the century, and to recount his career is to recapitulate the history of modern American show business. He began in vaudeville, first as a song-and-dance man and then as an emcee and comedian, working his way up from the amateur shows of his Cleveland hometown to headlining at New York’s legendary Palace Theatre. He segued to Broadway, where he costarred in some of the era’s classic musicals, appeared with legends such as Fanny Brice and Ethel Merman, and introduced standards by great American composers such as Jerome Kern and Cole Porter. Hope became a national star on radio, hosting a weekly comedy show on NBC that was America’s No. 1–rated radio program for much of the early 1940s and remained in the top five for more than a decade.

He came relatively late to Hollywood, making his feature-film debut, at age thirty-four, in The Big Broadcast of 1938, where he sang “Thanks for the Memory”—which became his universally identifiable, infinitely adaptable theme song and the first of many pop standards that, almost as a sideline, he introduced in movies. With an almost nonstop string of box-office hits such as The Cat and the Canary, Caught in the Draft, Monsieur Beaucaire, The Paleface, and the popular Road pictures with Bing Crosby, Hope ranked among Hollywood’s top ten box-office stars for a decade, reaching the No. 1 spot in 1949.

Nov. 19, 1952 – “Road to Bali” with Bing Crosby, Bob Hope & Dorothy Lamour

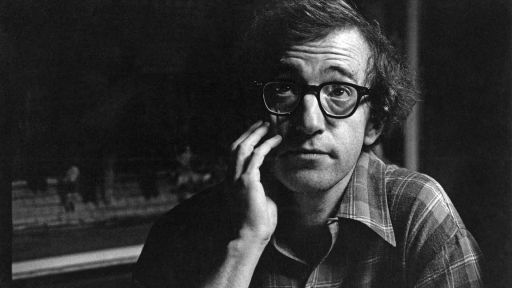

Hope brought a new kind of character and attitude to the movies. He was the brash but self-mocking wise guy, a braggart who turned chicken in the face of danger, a skirt chaser who quivered like Jell-O when the skirt chased back. “I grew up loving him, emulating him, and borrowing from him,” said Woody Allen, one of the few comics to acknowledge how much he was influenced by Hope—though nearly everyone was. Hope played variations on his cowardly character in spy comedies, ghost stories, costume epics, Westerns—but always with a winking nod to the audience, an acknowledgment that he was an actor playing a role. Especially in his interplay with Crosby in the Road films, Hope often spoke directly to the camera or stepped out of character to make cracks about the studio, his career, and his Hollywood friends. This improvisational, fourth-wall-breaking spirit was a radical break from the stylized sophistication of the 1930s romantic comedies, or the artifice of other vaudeville comics who transitioned into movies, such as W. C. Fields or the Marx Brothers. And it perfectly met the psychological needs of a nation at a time of war and world crisis. As the newsreels broadcast scenes of thundering European dictators, jackbooted military troops, and docile, mindlessly cheering crowds, Hope’s humor was both an escape and an affirmation of the American spirit: feisty, independent, indomitable.

When television came in, Hope was there too. Others, such as Milton Berle, preceded him. But after starring in his first NBC special on Easter Sunday in 1950, Hope began an unparalleled reign as NBC’s most popular comedy star that lasted for nearly four decades. Other comedians who made the move into television—Berle, Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Jackie Gleason, Danny Thomas, even Lucille Ball—had their heyday on TV and then faded; Hope alone remained a major star headlining top-rated TV shows well into his eighties. His 1970 Christ- mas special from Vietnam was the most watched television program of all time up to that point, seen in a now-unthinkable 46.6 percent of all TV homes in the country. (The final episodes of Dallas, M*A*S*H, and Roots are the only entertainment shows ever to beat it.)

That would have been enough for most performers, but not Hope. Along with his radio, TV, and movie work, he traveled for personal appearances at a pace matched by no other major star. He was just one of many performers who went overseas on USO-sponsored tours to entertain the troops during World War II. Unlike most of the others, he didn’t stop when the war ended. Starting with a trip to Berlin during a Cold War crisis in 1948, he launched an annual tradition of entertaining US troops around the world at Christmas—in wartime and peace- time, from forlorn outposts in Alaska to the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. Stateside, he was just as indefatigable, making as many as 250 personal appearances a year, manning the microphone at charity benefits, trade shows, state fairs, testimonial dinners, hospital dedications, Boy Scout jamborees, Kiwanis Club luncheons, and seemingly any event that could pack a thousand people into a ballroom on the promise that Bob Hope would be there to deliver the one-liners.

On a podium, no one could touch him. He was host or cohost of the Academy Awards ceremony a record nineteen times—the first in 1940, when Gone With the Wind was the big winner, and the last in 1978, when Star Wars and Annie Hall were the hot films. His suave unflappability—no one ever looked better in a tuxedo—and tart insider wisecracks (“This is the night when war and politics are forgotten, and we find out who we really hate”) helped turn a relatively low-key industry dinner into the most obsessively tracked and massively watched event of the Hollywood year.

Bob Hope with NBC Microphone for “The Pepsodent Show”

The modern stand-up comedy monologue was essentially his creation. There were comedians in vaudeville before Hope, but they mostly worked in pairs or did prepackaged, jokebook gags that played on ethnic stereotypes and other familiar comedy tropes. Hope, working as an emcee and ad-libbing jokes about the acts he introduced, developed a more freewheeling and spontaneous monologue style, which he later honed and perfected in radio. To keep his material fresh, he hired a team of writers and told them to come up with jokes about the news of the day—presidential politics, Hollywood gossip, California weather, as well as his own life, work, travels, golf game, and show-business friends.

This was something of a revolution. When Hope made his debut on NBC in 1938, the popular comedians on radio all inhabited self- contained worlds, playing largely invented comic characters: Jack Benny’s effete tightwad, Edgar Bergen and his uppity dummy, Charlie McCarthy, the daffy-wife/exasperated-husband interplay of George Burns and Gracie Allen. Hope’s monologues brought something new to radio: a connection between the comedian and the outside world.

Hope was not the first comedian to do jokes about current events. Will Rogers, the Oklahoma-born humorist who offered folksy and often pointed commentary on politics and the American scene, achieved huge popularity in vaudeville, movies, and radio in the 1920s and 1930s, before his death in a plane crash in 1935. Fred Allen, the frog-voiced radio satirist, was aiming acerbic and literate barbs at the potentates of both Washington and his own network while Hope was still apprenticing. But Hope was the first to combine topical subject matter with the rapid- re gag rhythms of the vaudeville quipster. His monologues became the template for Johnny Carson and nearly every late-night TV host who followed him, and the foundation stone for all stand-up comics, even those who rebelled against him.

Hope wasn’t a political satirist. His jokes never hit hard, cut deep, or betrayed any political viewpoint. Mostly they took personalities and events from the news and lampooned them for superficial things, or with clever wordplay—an ironic juxtaposition or unexpected twist or jokey hyperbole. “Not much has been happening back home,” Hope told a crowd of servicemen after the 1960 presidential election. “Hawaii and Alaska joined the union, and the Republicans left it.” He poked fun at new California governor Ronald Reagan for his Hollywood pedigree, not his conservative politics: “California’s back to a two-party system: the Democrats and the Screen Actors Guild.”

When Bobby Kennedy was thinking of running for president, Hope joked about the candidate’s growing brood of kids: “He may win the next election without leaving the house.” On hot-button issues such as gay rights, Hope’s gags amiably skirted any potential land mines: “In California homosexuality is legal. I’m getting out before they make it mandatory.”

He was the first comedian to openly acknowledge that he used writers—as many as a dozen at a time, turning out hundreds of potential jokes for each monologue. He saved them all, the keepers and the castoffs, in a fireproof vault in the office wing of his home in Toluca Lake, California—more than a million of them by the end of his career, all filed alphabetically according to subject matter (“Fairs, Fans, Finance, Firemen, Fishing . . .”). The jokes were rarely memorable, trenchant, or even very funny, and his dependence on writers would later be scorned by younger comedians, who mostly wrote their own material. Yet the jokes were always the weakest part of his act; his impeccable delivery is what put them across. The lamest formula gags could get laughs through the sheer force of his style and stage presence: the confident manner, the rat-a-tat pace and clarion tone of his voice, the perfect weight and balance given to each word, the way he barreled through a punch line and began the next setup (“But I wanna tell ya . . .”) until the laughter caught up with him—a technique that both bullied the audience into laughing and congratulated it for keeping up.

This was more than just the triumph of style over substance. Like the great pop and jazz singers of the pre-rock era, who performed songs written by others (before the Beatles came along, and singers had to become songwriters too), Hope was not a creator but a great interpreter. He didn’t necessarily say funny things, but he said them funny. Larry Gelbart, who wrote for Hope on radio for four years, before creating the hit TV series M*A*S*H, recalled watching Hope onstage at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre in 1948 and being surprised at the belly laughs he got for a joke whose punch line mentioned a motel.

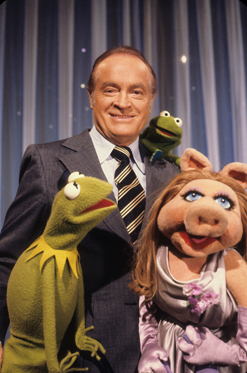

Dec. 19, 1977 – “Bob Hope All-Star Christmas Comedy,” featuring Bob Hope with Muppets Kermit the Frog & Miss Piggy

“Do you think anybody here knows what the word motel means?” Gelbart asked the pretty British girl he was with.

“No,” she replied.

“Then why were you laughing?”

“Because he’s so funny.”

Hope sold an attitude: brash, irreverent, upbeat. He was a product of Middle America—“the unabashed show-off, the card, the snappy guy who gets off hot ones at shoe salesmen’s conventions while they’re waiting for the girls to show up,” as humorist Leo Rosten once put it—who eased the country’s anxieties through complex and difficult times. The message of his comedy was that no issue was so troubling, no public figure so imposing, no foreign threat so intimidating, that it couldn’t be cut down to size by some good old American razzing. Hope’s comedy punctured pomposity and fed a healthy skepticism of politics and public figures. It helped Americans process changing mores, from new roles for women during World War II to the counterculture revolution of the 1960s. If the jokes were sometimes corny, even reactionary, Hope could be excused.

He transcended comedy; he was the nation’s designated mood-lifter. No one else could perform that role; few even tried. Comedians for years did impressions of Jack Benny, Groucho Marx, George Burns, and other classic clowns. Almost no one did Bob Hope. His ordinariness was inimitable.

Major support for This is Bob Hope… is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, National Endowment for the Arts, and Roslyn Goldstein. Major support for American Masters is provided by AARP. Additional support is provided by Rosalind P. Walter, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, Ellen and James S. Marcus, Judith and Burton Resnick, Vital Projects Fund, Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, The Blanche & Irving Laurie Foundation, and public television viewers.

The filmmakers and American Masters would like to thank our advisors for their time and expertise in making this documentary: James Baughman, Thomas Doherty, Michael Frisch, Kristine Karnick, Laurence Maslon, Clayton Koppes, Robert Snyder and Kathryn Fuller-Seeley.