Introduction: Into the Spotlight

By Ruth Feldstein

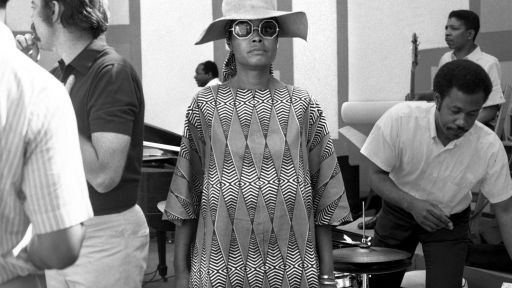

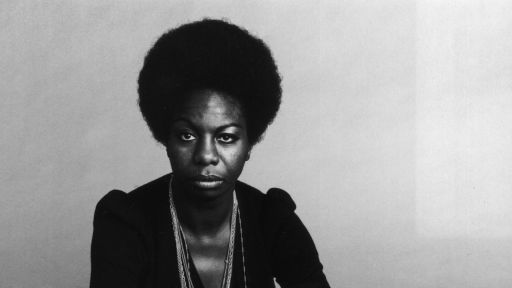

Lena Horne and five younger women performers – South African folk singer Miriam Makeba, jazz vocalist and pianist Nina Simone, jazz vocalist and film actress Abbey Lincoln, and stage, film and television actresses Diahann Carroll and Cicely Tyson – were among those entertainers who became prominent in the overlapping worlds of civil rights politics and entertainment. How It Feels to Be Free tells the story of this cohort of six black women entertainers, and the ways that they developed interrelated performance strategies and political positions during a long and multi-faceted civil rights movement. All six women used their status as celebrities to support black activism and played with gender roles as they performed black womanhood in new and distinct ways.¹ In their public performances and their political protests – and crucially in myriad instances when the lines between those blurred – all six drew attention to unequal relationships between blacks and whites and to relationships between men and women. As a result, even when they were part of larger groups of activist-entertainers who connected popular culture and racial politics, these women also stood out. Whether they were at jazz club in Greenwich Village, on a movie set in Hollywood, performing before a live television audience, or at an international music festival in France, Horne, Makeba, Simone, Lincoln, Carroll, and Tyson drew attention to the fact that they were women and black. In all sorts of ways, they insisted that the liberation they desired could not separate race from sex.²

The contributions that Horne, Makeba, Simone, Lincoln, Carroll, and Tyson made to black activism also affected another transformative social movement: second-wave feminism. These women did not necessarily call themselves feminists. But they offered critiques and demands that became central tenets of feminism generally and of black feminism specifically.³ With some good reason, many people associate women’s liberation with white women, but these black women performers shift attention beyond famous markers like publication of The Feminine Mystique in 1963 or protests at the Miss America pageant in 1968. In the late 1950s, Abbey Lincoln rejected comparisons between herself and Marilyn Monroe and rejected a route toward celebrity based on tight-fitting and revealing gowns. A few years later, Nina Simone sang about the rage of a black woman domestic in her remake of “Pirate Jenny.” Black women entertainers’ politicized performances suggest that a concern with gender politics did not necessarily develop out of or after concerns with racial politics, precisely because they were among those who addressed issues of race and gender and, often, class at the same time.4

With fans around the world and ties to different countries, these six black women performers, and their activism on and off-stage, had international dimensions. They traveled extensively and were able to export ideas about black protest and gender at the same time that the people they met and the experiences they had outside of the United States had an impact on the choices that they made domestically. Through their work as entertainers, popular culture and civil rights together crossed borders, affording consumers opportunities for pleasure and commitment.5

With fans around the world and ties to different countries, these six black women performers, and their activism on and off-stage, had international dimensions. They traveled extensively and were able to export ideas about black protest and gender at the same time that the people they met and the experiences they had outside of the United States had an impact on the choices that they made domestically. Through their work as entertainers, popular culture and civil rights together crossed borders, affording consumers opportunities for pleasure and commitment.5

Lena Horne, from the start of her career in the 1930s into the 1960s, and Miriam Makeba, Nina Simone, Abbey Lincoln, Diahann Carroll, and Cicely Tyson from the late 1950s onward all worked hard to control their public images. But people loved to talk and write about famous stars and celebrity culture, and these women set into motion widespread conversations among critics, fans, and activists that they could not always control. Their political significance developed out of the cultural work they did and their efforts at self-representation, as well as the ways that fans and critics reacted to them and produced them as celebrities. The music the women sang, the records they sold, and the films and television shows in which they appeared were not direct extensions of pre-existing political organizing or ideologies and were not mirrors that simply reflected back pre-existing black activism. Miriam Makeba’s “The Click Song,” for instance, did not at first glance seem to be political in any way. However, her encounters with audiences when she performed this celebratory melody transformed the literal meaning of the lyrics. Performances and reactions to these performances together shaped dialogues about race relations and gender. These, in turn, contributed to shifting expectations about freedom for black Americans and about relations between the sexes.6

In short, “How It Feels To Be Free” suggests that a fuller understanding of black activism and feminism requires expanding the realm of political activity. Ministers, marches, activist leaders, grassroots organizers, and legislation were all important to the way that civil right politics became relevant to ordinary Americans and non-Americans outside of political organizations, but so too was a global mass culture in which these black women played a crucial role. The ways in which they came to “perform civil rights” – the ways that their on and off-stage appearances, and reactions to these appearances became ground on which both performers and audiences made sense of black activism – helped constitute the political history of this period.

From How It Feels to Be Free by Ruth Feldstein. Copyright © 2013 by Ruth Feldstein and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

1For how women entertainers “improvised” gender and womanhood, see Sherrie Tucker, “Bordering on Community: Improvising Women Improvising Women-in-Jazz,” in Daniel Fischlin and Ajay Heble, ed., The Other Side of Nowhere: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), pp. 244-267. The literature on black women, race, and performance is extensive. In addition to work cited in each chapter, useful theoretical and historical analyses include Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008); Donald Bogle, Brown Sugar (New York: Crown, 1980); Stephanie Baptiste, Darkening Mirrors: Imperial Representation in Depression-Era African American Performance (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister-Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011); Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), pp. 85-169. For black women musicians negotiating race and gender, see Eileen M. Hayes and Linda F. Williams, ed., Black Women and Music: More Than the Blues (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

2In considering black women entertainers as activists, intellectuals, and political subjects, and not exclusively as performers or the object of an audience’s gaze, I draw on Hazel Carby’s landmark, Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990). See also, James C. Hall, “The African American Musician as Intellectual,” in Jerry G. Watts, ed., Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual Reconsidered (New York: Routledge, 2004), pp. 109-119. Although work on the women who are my focus has increased (in part since the deaths of Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, Lena Horne, and Abbey Lincoln), they remain ancillary to most civil rights histories oriented toward traditional political organizing and movements, including important work oriented toward women as movement leaders or local grassroots activists. Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday remain the black women entertainers about whom a great deal has been written. See, for example Jeanne Scheper, “‘Of la Baker, I Am a Disciple’: The Diva Politics of Reception,” Camera Obscura 65 (2007): 72-101; Mathew Guterl, “Josephine Baker’s ‘Rainbow Tribe’: Radical Motherhood in the South of France,” Journal of Women’s History 21 (2009): 38-58; Farah Jasmine Griffin, If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday (New York: Ballantine, 2001).

3For the development of black feminist theory, see, for example, Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 1990); Gloria T. Hull et.al., eds., All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us are Brave: Black Women’s Studies (New York: Feminist Press, 1982); Joy James, Shadowboxing: Representations of Black Feminist Politics (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999). For black feminist organizing (and the term’s meanings among African American women), see especially, Kimberly Springer, Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968-1980 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

4For a classic and still influential analysis of second-wave feminism developing out of and after a commitment to civil rights, see Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left (New York: Vintage, 1979). For intertwined relationships between black activism and black feminism, see, for example, Angela Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (New York: Vintage, 1998); Lisa Gail Collins, “The Art of Transformation: Parallels in the Black Arts and Feminist Art Movements,” in Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie Crawford, eds., New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, 2006), pp. 273-296; Dayo Gore, Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists and the Cold War (New York: New York University Press, 2011); Christina Greene, “What’s Sex Got to Do With It?: Gender and the New Black Freedom Movement Scholarship” Feminist Studies (March 2006): 163-183; and Anne Valk, Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2010). See also the landmark anthology, Toni Cade, ed., The Black Woman: An Anthology (New York: New American Library, 1970). For the multiple histories, origins, and implications of second-wave feminism, see, for example, Dorothy Sue Cobble, The Other Women’s Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005); Jane F. Gerhard, The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2013).

5Work on gender, culture, and the transnational dimensions of civil rights that has shaped my thinking includes Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Kevin Gaines, “From Center to Margin: Internationalism and the Origins of Black Feminism,” in Russ Castronovo and Dana Nelson, ed., Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics, ed., (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), pp. 294-313; Penny Von Eschen, Satchmo Blows Up the World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

6Stuart Hall, “Notes on Deconstructing ‘the Popular,” (1981), in Raiford Guins and Omayra Zaragoze Cruz, eds., Popular Culture: A Reader (London: Sage Publications, 2005), pp. 64-71; Stuart Hall, “What is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” in Gina Dent, ed., Black Popular Culture (New York: New Press, 1992), pp. 21-33; Richard Dyer, Stars (London: British Film Institute, 1998); Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (New York: Routledge, 2004).