In the 1950s, the film industry was once again in a moment of reckoning as Hollywood faced the post-war breakup of its monopolies. Beforehand, the major studios controlled the entire cinematic pipeline in which production, distribution, exhibition and talent were all governed through oppressive contracts. In disrupting this self-contained system, the Golden Age of Hollywood would come to its end.

Among the many filmmakers to emerge from the studio system, Billy Wilder’s name is often synonymous with the Golden Age era. Despite running into criticism for his cynical sense of humor, Wilder’s films like “Double Indemnity,” “The Seven Year Itch” and “Some Like It Hot” made him one of the most successful directors of his time. As the government was just beginning to enforce its shakeup of the studio system, Wilder was developing a project about Hollywood itself.

The impending changes echoed the industry disruption created by sound decades prior, which had pushed actors to retirement and forced studios to re-evaluate the business.

“For a long time I wanted to do a comedy about Hollywood. God forgive me, I wanted to have Mae West and Marlon Brando. . . Instead it became a tragedy of a silent-picture actress, still rich, but fallen down into the abyss after talkies,” he said.

From this idea evolved “Sunset Boulevard,” the story of Norma Desmond – a forgotten silent film star dreaming of her grand revival. Though Desmond’s quest for fame is presented as grotesque (she is only 50 years old), the film touches on the precarious relationship of studio and star of both eras:

“Without me there wouldn’t be any Paramount Studios,” declares Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond, echoing Mae West’s real life declarations of saving Paramount years prior.

Drawing from life, the film capitalized on Gloria Swanson’s own biographical similarities to her character. (Though in contrast, Swanson had a moderately successful career in the “talkies.”) But Swanson was not the only actor to have a personal parallel, as Wilder included other silent film figures for smaller roles. In particular, one scene offers close-ups around a game of bridge with Desmond’s old companions, patronizingly referred to as “the waxworks.” Wilder described his idea for the scene in an interview for The Paris Review:

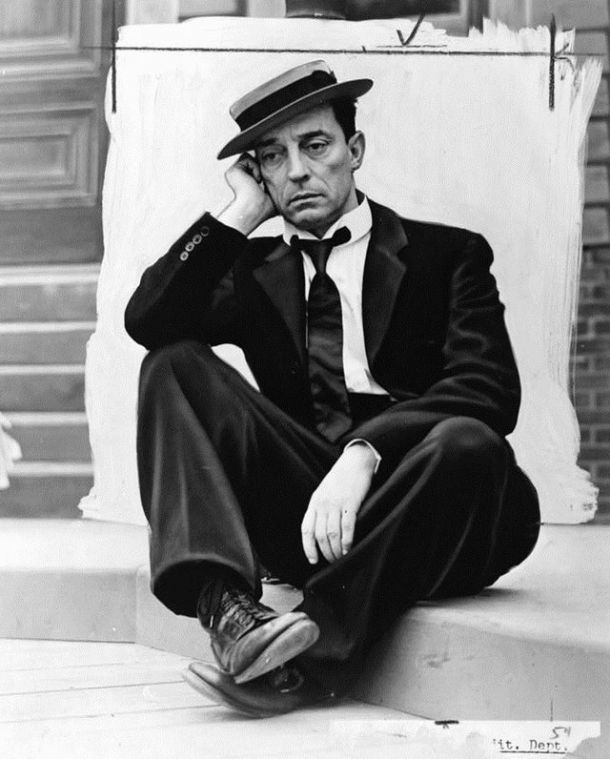

“I thought, now, if there is a bridge game at the house of a silent star, and if I am to show that our hero, the writer, has been degraded to being the butler who cleans ashtrays, who would be there? I got Harry B. Warner, who played Jesus in [Cecil B.] DeMille’s biblical pictures, Anna Q. Nilsson and Buster Keaton, who was an excellent bridge player, a tournament player.”

Though Keaton’s career revival would arrive soon thereafter, his participation is practically mocked by Wilder:

“The picture industry was only 50 or 60 years old, so some of the original people were still around. Because Old Hollywood was dead, these people weren’t exactly busy. They had the time, got some money, a little recognition. They were delighted to do it.”

There’s an irony to pitying the passé of “Old [dead] Hollywood” versus the forthcoming demise of the Golden Age, which Wilder himself would later struggle in. Though ahead of its time with meta-commentary about the film industry, the Hollywood in “Sunset Boulevard” is one wavering on the failing studio system. Desmond is sneered at by the younger characters and turned away by the studios — the studios she originally carried to triumph. Notably, Buster Keaton had faced his own fallout with the studio system years prior. Following the advent of sound, Keaton had signed a studio contract he felt completely destroyed his career.

Alongside Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, Keaton was one of the biggest stars of the silent era.

His films showcased remarkable stunts, slapstick and special effects withstanding the test of time. For most of the 1920s, Keaton functioned as an independent with complete creative control, relying on his producing partner Joe Schenck to negotiate distribution deals with studios.

In 1926, Schenck became the president of United Artists, distributing three Keaton films under their banner to disappointing financial returns. Schenck advised that Keaton move onto another studio and made a deal to sell Keaton’s contract to M-G-M in 1928 for an impressive $3000 weekly salary and a percentage of film gross. However, Keaton would go on to describe this move as “the worst mistake of my career” in his autobiography.

“Don’t do it. They’ll ruin you helping you. They’ll warp your judgment. You’ll get tired of arguing for things you know are right,” advised Charlie Chaplin.

But Keaton was tempted by the lucrative offer. Upon signing, he was at the mercy of the studio system and M-G-M would severely limit his creative control. “The worst shock was discovering I could not work up stories the way I’d been doing . . . they complicated our simple plot with everything they could think of . . . with so much talk going on, so many conferences, so many brains at work, I began to lose faith for the first time in my own ideas,” he wrote.

Although his early films with M-G-M generated some commercial success, Keaton disliked the studio process turning his work into something other than his own. Sound similarly disrupted his style as studio scripts relied heavily on quick, constant dialogue and forced actor pairings that conflicted with Keaton’s strength for comedic pantomime. Struggling through divorce, bankruptcy and alcoholism, Keaton was fired by M-G-M in 1933.

“Losing out at M-G-M made me poison at the other major Hollywood studios. None of them seemed to want or need me. I don’t know what wild rumors went around about my unreliability and alcoholism. But in that tightly knit one-industry town there were then seven major studios in a position to spend on a picture the sort of money that my comedies cost. No offers came from the other six: Paramount, Columbia, Warner Brothers, Universal, Fox, or RKO.”

Just as the studio system faced its own falls and re-inventions, Keaton’s career naturally ebbed and flowed in the time he worked through finding sobriety.

He continued to struggle with his health and finances, returning to M-G-M in 1940 for $100 a week as a comedy consultant. Through this humbling period, Keaton was able to re-establish himself and find new passion for the burgeoning television industry. His job also offered him flexibility to take small acting roles like in “Sunset Boulevard,” where “waxwork” Keaton sheepishly only utters one word:

“Pass.”

Though time marches on for all artists and Keaton did find renewed celebrity in the following years (particularly in television after leaving M-G-M in 1949), his cameo in “Sunset Boulevard” captures a life’s moment of poignant humility.

“Pass,” said by the “Great Stone Face” himself, whose wide shifting gaze seems to be saying so much more: Past one’s prime, passed over, time passing on.

And it feels as if with that one word, one look, that this brief appearance encompasses all that history.

Work Cited