Pearl Jam in concert: Mexico City, Mexico, 11-24-11 | photo: Official Pearl Jam photo by Karen Loria

By CAMERON CROWE

A note to the reader: the following is excerpted from the introduction to the book, PEARL JAM TWENTY.

I’ll admit this to you right now. I’m a collector. I’ll keep anything and everything. I’ll keep a record, a receipt, a photo, a magazine, a card, a phone number long since disconnected. Everything. Any artifact that passes through my life is worthy of stuffing in a box and saving for appreciation on some distant later day. It’s a bit of a burden, as any collector knows. At some point, the boxes own you. Moving is a horrific experience. And actually finding something you’re looking for in these towers of boxes is always a futile endeavor. But there they sit, the boxes, and every once in a while, this pack-rat mentality can be a little bit profound. Like today, randomly coming across two dusty containers. One of them is marked with a heavy black felt tip pen: Pearl Jam—Stuff/’90s. And next to it is another box: PJ 2000s. All saved for a rainy day, and here it is. Raining.

The timing is interesting. We’ve been in the editing room for about a year, working on a film celebrating the band’s first twenty years. I thought we’d searched every corner and crevice, called in every random news report and interview from every foreign market, transferred every essential piece of Super 8 from the band’s visual archivists—and now I find more stuff. My own stuff, much of it too late to make the movie but just in time to make writing this introduction a little bit of a travelogue through the mementos and feelings from my own lucky first-row seat near the birth and amazing journey of this truly great American band.

They’ve grown from earnest young musicians, thrashing through their influences and emotions, hearts on their sleeves, to unjaded and barely prepared travelers through the portal of enormous international success, to unashamed participants in the politics of world events, to what they are now: musical survivors with passion unscathed. A Pearl Jam concert today is about much more than music. It’s about the kind of clear-eyed spirit that comes from believing in people and music and its power to change a sh–ty day into a great one, or looking at an injustice and feeling less alone about facing it. If anything, that’s the through-line in their twenty years. As bassist Jeff Ament told us, “There’s not a single night I can remember when we were just going through the motions. Every night is just”—and here Jeff smiles with a touch of wonder—“pure stoke.”

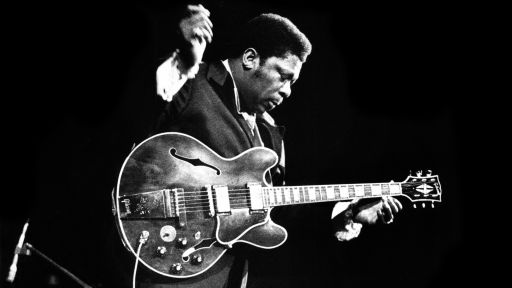

The boxes are filled with tapes and notes and bootlegs and music and notebooks. Digging deeper, there’s a carefully adorned airplane vomit bag with these words on it, drawn in an inky sparkly pen. It reads: “From Eddie.” And in it is an Ampex brand tape of early demos. I remember this tape. We were starting to make the movie Singles, in 1991, and we’d given the band jobs in and around the set. Jeff worked in the art department, and I’d borrowed much of his own stuff to decorate the apartments in the movie. Jeff had the greatest synthesis of art, sports, and film, all on his walls. From David Lynch, to obscure metal, to King’s X, to players on the Supersonics, and more. (Sorry we lost some of your vinyl and that Joe Perry Project poster; I owe you an eBay replacement search, brother.) That Cuisinart mix of all that was important artistically and soulfully had a big effect on the ethic that would later spawn Pearl Jam. Art is everything, Jeff seemed to be saying with his life choices. (The creative wanderlust had drawn him from Big Sandy, Montana, to the comparative artistic mecca of Seattle.) Jeff’s taste, and that of his musical cohort, guitarist Stone Gossard, was inspiring and genre bending, too. It was okay to like disco, hard rock, Kiss, Queen, and the blues. It all came out in their music, in the dark promise of their early band, Green River.

And look, here’s a photo of the Seattle sky, late eighties. A dark blue horizon speckled with bright Northern stars—that’s what the music sounded like then, indigo, flashy, melodramatic, and fun, too. With a sky like that, it’s hard not to look up. And it’s hard not to feel it, even locked away in a garage, slashing through chords and looking for the right mix of influences. It doesn’t always rain in Seattle, but certainly music from the Northwest has its roots in players who stay indoors and play and listen and listen and play. A lot. Thus, the tradition of musicians who have the time to feel it and get it right.

Even from the beginning, there was a generosity about Pearl Jam. Jeff and Stone, guitarist Mike McCready, and, later, Eddie, all had an openness to music and the world, and an almost superstitious attention to the details of how this band would be different. The band itself sprung from a miracle. Stone and Jeff had been playing with a local luminary, Andrew Wood, a singer and writer of monumental charisma and talent. When Wood died from a heroin overdose on the eve of Mother Love Bone’s first big tour, the loss was beyond seismic. Wood’s garrulous spirit drew people to him, it was hard to forget him, but when a demo tape for Gossard and Ament’s next musical project went forth into the world and found its way to a young San Diego surfer who connected immediately, no one could at first believe lightning could strike again, much less that fast. Before long, the shy surfer, Eddie Vedder, was sitting among us, staring down behind a sheet of wavy brown hair, barely speaking but trying to fit in. And every once in a while, Vedder would pull the hair out from in front of him, and look at us with those flashing, mischievous eyes and . . . you knew. This was a guy who shared the same high-stakes love of all that was possible.

One night, sitting cross-legged at a friend’s house, listening to Neil Young tapes, Eddie told me the story of discovering that his biological dad was actually a family friend who’d passed away. It was a brief moment of somber reflection from Eddie, almost a confession about where some of the finely etched anger in his songs was actually coming from. But mostly we talked about Pete Townshend of the Who. Townshend is still a hero to both of us. Besides the Who, then unchallenged as the greatest band in rock, we both loved the Rolling Stone journalism of Townshend. Townshend still is rock’s most articulate spokesman, surely the best rock journalist of them all, because he wrote from the inside out. Townshend wrote about a healing belief in the power of rock. There was nothing jaded and diseased about his relationship with music. His love of rock was almost religious, and so fervent that when the famous anarchist-politician Abbie Hoffman tried to grab a microphone and say a few words in the middle of the Who’s performance at Woodstock, Townshend famously swatted him from the stage with his guitar. Hearing Eddie’s recording on that first demo, I felt that same fervor. The music was a sanctuary, a place where something more than just rock might occur. Like the others, Vedder was a fan, and any fan knew that, handled correctly, music could take you rushing down the current to places you’d never imagined. That is, if you cared enough. And concentrated enough. This would be an experiment in alchemy. “I just want to play,” I remember Eddie saying. “Just want to keep playing.”

Message: No bullsh– need interrupt.

Over time, Eddie’s voice began to change. Those first few months, he’d carried himself with the demeanor of a guest at a dinner party he’d never expected to attend. Grateful, quiet, loving, and sweet. There’s a moment in the film, Pearl Jam Twenty, when he speaks to band videographer Kevin Shuss after an early show. Flushed with the experience of what had just happened on stage, he alternately tells Kevin to f— off, and then tells him he has three words for him: “I love you.” That lopsided, sparkly smile, just before he exits frame—that was the Eddie Vedder who arrived in Seattle with a pocketful of dreams. He was immediately loved by strangers, and he also knew that he was carrying the hopes of all those Seattle players and friends and families who’d lived through the loss of Andy Wood and wanted badly for this group to succeed.

The audience for the band’s first show at the Off Ramp was filled mostly with anxious and hopeful supporters. Eddie was nervous, swaying backward and forward, side to side, holding onto the mike stand like a young captain steering a pontoon ship. The songs are what stood out. Confident, honest, and memorable, there was one song that towered over the rest to me. “Release” was a song written from way down deep, filled with openhearted emotion. It reached people instantly. That galvanizing moment, with audience and band coming together, set the stage for all that would follow. They changed their name to Pearl Jam. Soon the tornado of success would touch down, and all that followed was a lesson in learning on the job.

The songs guided them through the first album. The songs moved people, showed them a new style of commitment that had been increasingly absent in rock, and sure enough, in shockingly short order, the enormity of the group’s popularity found them living under the white-hot heat of scrutiny. They proceeded in their own fashion, with ever-changing shows, and ever-changing rhythms, always staying close to their original instincts. Their original manager, Kelly Curtis, is still their manager. He, too, guides the band with a simple credo: Stay true to the music.

It’s hard for a band to stay together. Success becomes its own built-in morphing machine. Friends and family change and shift, the bar for expectations changes, the financial issues sprout thorns and dissatisfaction. Cool heads grow hot with emotion. And then there are the distractions: side careers, drugs, lifestyle, bigger houses, and more. Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell has a curious question, with no answer. “Why is it that American bands never stay together? It’s the English bands, like the Rolling Stones or the Kinks—they stick around—but the American bands, they’ll have one or two hits, and then one of them knocks over a grocery store and goes to jail, or gets on drugs, or decides he’s the real leader and . . . it’s over.” Cornell shakes his head. “Early on, Pearl Jam had this positivity . . . and promise. A promise of integrity and faith that if you believe in us, we won’t turn around and sh– on you down the line.” He laughs. “They made good on that promise, which is almost more important than just staying together.”

I’m now opening the second box: PJ 2000s.

Here we see the second ten years, and the second act of a band that survived that first tidal wave of popularity. One of the surprises, picking through the artifacts, tour passes, press, and more, is that their stubbornness as artists sometimes had media detractors. At times, even other bands found Pearl Jam’s steadfast desire to keep playing, but grow smaller, absolutely confounding. The band would swear off videos and most interviews for years. That stubborn muscle was always there in them, though, all the way back to Vedder refusing to release “Black” as a single from Ten, even when all the record company bigwigs and radio station programmers were bombarding the band with demands for it. A note in the box, from the early 2000s, a conversation with Bono, and the subject of Pearl Jam comes up. “I don’t understand it,” Bono exclaims. “It’s lonely being us, we want the competition, we want the music . . . I keep telling Eddie, ‘Why don’t you just make a f—ing great rock record. Like the Rolling Stones used to! A great summer rock record filled with singles. Is it so hard? It’s your responsibility.’ They could be the greatest, biggest rock band in the world! Come on, Eddie!!!!” Bono paused. “I call him and tell him this. Why doesn’t he listen?”

With the gift of clarity and ten years, it’s now obvious that Pearl Jam did listen. They just didn’t follow. Vedder, then guiding much of Pearl Jam’s creative destiny, had his own course charted. It seems visionary now, but at the time, carefully pitching Pearl Jam away from a pursuit of global commercial domination seemed almost unfathomable. What band actively seeks . . . less? The answer lived in the group of fans that stayed with the band past the first explosive wave. The answer was onstage.

To anybody who lost track of Pearl Jam for a few years in the later nineties or the early 2000s, a surprise was awaiting them when they’d drop in on a live show. There was a passionate theater or arena filled with followers, keyed to nearly every lyric, and many of them had followed the band from show to show. It was not dissimilar from what Jeff Ament had seen in the nineties, checking out a series of Grateful Dead shows. He was blown away at the lack of distance between fan and band, and “the fact that they would get the greatest response from playing an obscure song they hadn’t played in seventeen years. I remember looking at that and thinking, That’s success.”

“All that’s sacred comes from youth,” Vedder once wrote in the song “Not for You,” but time has perhaps offered him a different perspective. He now charts the power of the lengthening career of Pearl Jam by watching the ongoing inspiration that is Neil Young’s powerful body of work, or to the longtime surfers he sees in the water. They’re the ones who are the wiliest, says Vedder, and they know how to seize the bigger waves better than the young ones, and with a minimum of wasted effort. A different kind of fervor also now fuels him. A father of two kids, blessedly too busy to ruminate much about his own complex childhood anymore, Vedder is writing with greater precision and depth with ease, and no less passion. While the others continually point to Eddie’s growth and comfort in his own skin, and the inspiration that comes from working shoulder to shoulder with his committed love of their work together, Vedder himself points to the other members as the key: the graceful power of McCready’s guitar, Stone Gossard’s mercurial creative genius, Ament’s soul and drive and artistic barometer, Matt Cameron’s band-saving steadfastness, and even the well-fated arrival of Boom Gaspar on keyboards, allowing the group to perform anything from its entire history on stage.

This book (Pearl Jam Twenty) is based on twenty years of interviews with the band, conducted from those early days, to our filming for Pearl Jam Twenty. They range from formative Seattle interviews to tour conversations done at soundchecks, or during recording, to chats recorded between takes on Singles, to recent conversations conducted by Jonathan Cohen based on his own meticulous research. I still don’t know how Cohen found time to lash much of this together while still holding down his daily job of booking music for Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. But alas, such is the Herculean ability of a Pearl Jam fan on a mission.

Thanks also to the band members themselves, for opening up their homes, lives, and archives to us. They are friendly but private guys, as their fans know well. So the very act of releasing this bounty of information and souvenirs, clues and myths and facts, is all part of the group’s ongoing sense of reinvention. Some might have never expected such an open book approach. But then again, as we say in Pearl Jam Twenty, they have become over time the most dependably unpredictable band in rock.

Enjoy this map of a journey fueled by passion, music, instincts, humor, love, and the power of that moment in the dark when Pearl Jam takes the stage and everybody wonders, Where will they take us now? On that note, I will begin a new box, and dedicate it to a few of the indelible characters without whom I wouldn’t have this rich treasure trove of memories and music from twenty years of loving the band. Thanks Nancy, Buddy, Kelly, Eric, Jeff, Stone, Eddie, Mike, Dave, Jack, Matt, Chris, Kevin, George, Pete, and Neil. Happy birthday, guys.

Turn it up!