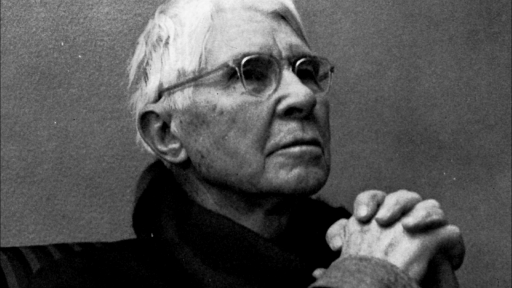

Shut your eyes and think of Carl Sandburg: a boy’s haircut all matted down, a warm face cut from hard stone. Now think of that man–his lanky figure in an old suit and an unpressed shirt–walking step for step with Paul Bunyan, setting up a rail spike for John Henry.

What you’ve got is a tall tale.

Yes, Sandburg was only a man. But, his words were Paul Bunyan; his words were John Henry: impossibly real.

You can see it in his poem, “A Tall Man” from Cornhuskers in 1918:

The jaws of this man are bone of the Rocky Mountains, the Appalachians.

The eyes of this man are chlorine of two sobbing oceans,

Foam, salt, green, wind, the changing unknown.

The neck of this man is pith of buffalo prairie, old longing and new beckoning of corn belt or cotton belt…

The way Sandburg wrote, he gave life to anything and everything around him: from mountains to oceans, from prairies to rows of corn or cotton.

Skyscrapers, too. That’s what Sandburg did in Rootabaga Stories, published a few years after Cornhuskers in 1922. Just as L. Frank Baum takes you to Oz, Sandburg takes you to Rootabaga Country. It’s a make-believe American Midwest: somewhere between Kansas and Kokomo, Canada and Kankakee, Kalamazoo and Kamchatka and the Chattahoochee.

“I wanted something more in the American lingo,” Sandburg once said. “I was tired of princes and princesses and I sought the American equivalent of elves and gnomes.”

You have to read Rootabaga Stories to get at what Sandburg meant exactly. Because before Sandburg, America already had its elves and gnomes: Rip Van Winkle, the Devil and Daniel Webster, the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion, to name a few. What Sandburg made new was a country where skyscrapers talk to each other and fall in love, where children name themselves names like “Gimme the Ax,” and where a Potato Face Blind Man is your guide.

You could call all this nonsense. Because in Rootabaga Country there are crops of balloons that are really potatoes and the capital city is the Village of Liver and Onions. But, what Sandburg did was wrap American industry and agriculture in a child’s daydream. He made a hardy and hard land–think smokestacks and rail tracks, think scaffolding and harvesting–sweet and soft. So that buildings breathed and crops moved just like you and me.