by Pat Kirkham, author of Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Century (MIT Press)

Charles and Ray Eames “pinned” by chair bases, 1947. © 2011 Eames Office, LLC.

Charles and Ray Eames headed the most creative design office in post World War II America. Frequently photographed in matching clothes, poses, or both, each brought a rich array of talents to their life/work partnership (1941-1978) as well as a contagious enthusiasm for life and art.

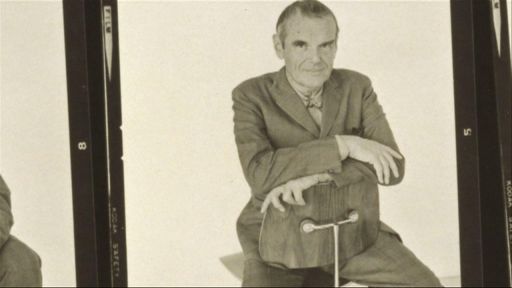

Dazzlingly bright-eyed, Ray looked like a cross between Dorothy in the enchanted Land of Oz and an artistic version of the energetic and engaging Jo March in Little Women. Charles, who looked film star Henry Fonda, was handsome, charismatic and thought by many to be a “genius”.

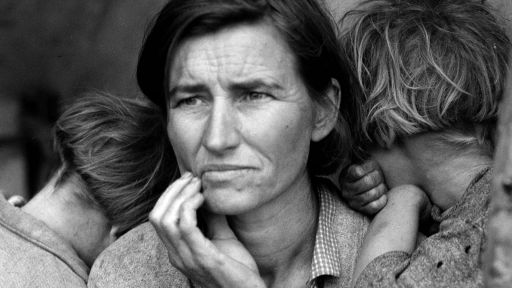

Their studiously simple lifestyle revolved around their “laboratory” workshop and office in Los Angeles. No one worked harder than this pair; and no one took greater pleasure in their work. Together, they (and those who worked in the office) created some of the most iconic furniture of the twentieth century, which, together with their architecture, interiors, films, multi-media shows and exhibitions helped shape how people thought about objects and buildings.

Ray (1912-1988) studied art in the 1930s with Hans Hofmann, the famous German émigré painter and teacher, becoming an accomplished painter and sculptor with a strong sense of structure. Together with fellow Hofmann students, including Lee Krasner, Lillian Kiesler, Mercedes Carles Matter, Harry Holtzman, and Benjamin Baldwin, Ray joined the American Abstract Artists, a militant organization that picketed galleries refusing to show non-representational art, showed in exhibitions between 1937and 1941, years in which Jackson Pollock, Willlem de Kooning, and Clement Greenberg also came into the Hoffman circle. Thus, Ray was part of an art movement that fed into American Abstract Expressionism, a movement that in the 1950s came to dominate the international art world. It is no coincidence that the Eameses’ most exciting and popular furniture designs were created in that decade and owed much to Ray’s close familiarity with modern art.

Charles’ (1907-1978) route to modernism was more varied. Despite his high practical and engineering skills and an outstanding talent for “problem solving”, he was asked to leave his Beaux-Arts orientated architecture course in 1927, after only two years because he had demanded a greater focus on modern work, particularly that of Frank Lloyd Wright, and wanted to design in more modern ways. He visited Europe that year with his bride, Catherine Woermann, a fellow architecture student, seeing all manner of buildings, including International Style modernist housing. The European modernists made a great impression on Charles, but returning to the U.S. at the dawn of the Depression Charles and his architectural partners took what work they could, from Colonial Revival, “Art Deco” and “Swedish Grace” style homes.

He took “time out” from work and his family, including his young daughter, Lucia, in Mexico in 1933. Upon his return he found several important commissions, including a Catholic church in Helena, Arkansas. That building impressed Finnish architect and designer, Eleil Saarinien, who directed the renowned Cranbrook Academy, the art and design school not far from Detroit. In 138, Charles was invited to Cranbrook, where he planned to spend his year-long fellowship reading and re-focusing but ended up heading a new design department. Cranbook deepened his respect for humanistic approaches to design as well as modernism. In collaboration with Eero Saarinen (Eliel’s son), Charles began exploring the possibilities of new materials and techniques, particularly molded plywood. The molded plywood furniture Eames and Saarinen designed for a 1940 competition organized by the Museum of Modern Art to encourage American furniture designers to create new forms capable of being produced commercially brought them considerable attention. The technologies proved inadequate but fortunately war intervened before this became well known.

Charles also met Ray at Cranbrook and when they married they moved to Los Angeles to focus on the mass- manufacture of low-cost molded plywood furniture; getting what Charles called “ the most of the best to the most for the least”. Ray’s stunning graphics and textiles of the early and mid-1940s indicate a strong independent design talent but she chose (as did many women of her generation) to work jointly on a project that she did not originate. By 1951, they had seen through to commercially viable mass production low-cost furniture in plastic and metal as well as plywood; the first people to so do.

Their colorful ESU storage unit (1950) and the front facade of their house (1949, Pacific Palisades, California) (1945-49), reflected Ray’s huge interest in Mondrian. A minimalist structure of standardized parts, their house was personalized and aestheticized by carefully-arranged displays of widely disparate objects placed in juxtaposition to one another. It was an aesthetic of cross cultural reference, layering, accretion and sheer joy in objects. “Ordinary” and “found” objects were considered as worthy of inclusion as Hofmann paintings (hung from the ceiling); toys, stones, driftwood, starfish, chocolate bars, combs, candelabras, souvenirs, masks, rugs and pillows all were fair game in ever-shifting collages. Much admired today, at the time this type of interior decoration was one of the few projects for which Ray was always given full credit, largely because she was blamed for something that was seemingly antithetical to the modernist stance against decoration. Robert Venturi later applauded it, claiming the Eameses had re-introduced “Victorian clutter”, and today it is regarded as one of their most fascinating contributions to Mid-Century Modern design.

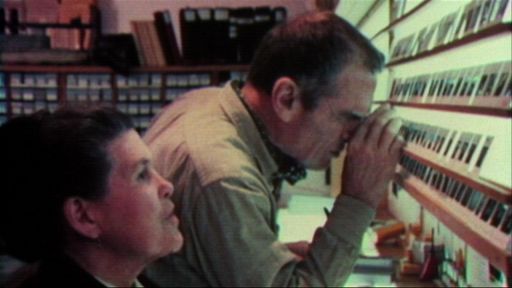

Ray and Charles Eames selecting slides for the exhibition, “Photography & the City, 1968.” © 2011 Eames Office, LLC.

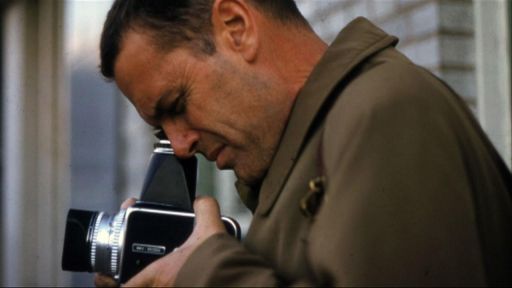

By the late 1950s, the Eamese focused more on communications than products, creating films multi-media presentations and exhibitions which shaped the ways people thought about objects, ideas, history, and science. The “overload” of objects in their home was paralleled in the “information overload“ of their media work. They believed that viewers or visitors were capable of negotiating their own ways through complex and diverse material – a commonplace concept today but considered revolutionary at the time – and used all manner of effects, from puppet shows to timelines, inter-active “games”, and animation, to enhance the learning process. One of their most important contributions to American culture in the1950s and 1960s was to help popularize the computer, then feared as an alien product which could be used to control humans. Symbols of humanity and love (hearts and flowers –decidedly romantic, decidedly anti-modernist and very much a Ray “touch”) emphasized the human dimension just as their Glimpses of the USA, 1959, brought the everyday aspects of life to the attention of the Russian people during the Cold War.

After Charles’s death in 1978, Ray began to sort their enormous archive with a view transferring it to the Library of Congress. She died ten years to the day after Charles.